Poincaré–Hopf theorem

In mathematics, the Poincaré–Hopf theorem (also known as the Poincaré–Hopf index formula, Poincaré–Hopf index theorem, or Hopf index theorem) is an important theorem that is used in differential topology. It is named after Henri Poincaré and Heinz Hopf.

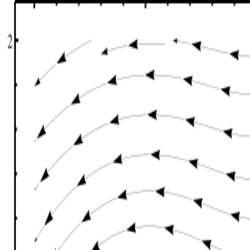

The Poincaré–Hopf theorem is often illustrated by the special case of the hairy ball theorem, which simply states that there is no smooth vector field on an even-dimensional n-sphere having no sources or sinks.

Formal statement

Let [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] be a differentiable manifold, of dimension [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] a vector field on [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]. Suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is an isolated zero of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math], and fix some local coordinates near [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Pick a closed ball [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] centered at [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], so that [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is the only zero of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math]. Then the index of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{index}_x(v) }[/math], can be defined as the degree of the map [math]\displaystyle{ u : \partial D \to \mathbb S^{n-1} }[/math] from the boundary of [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] to the [math]\displaystyle{ (n-1) }[/math]-sphere given by [math]\displaystyle{ u(z)=v(z)/\|v(z)\| }[/math].

Theorem. Let [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] be a compact differentiable manifold. Let [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] be a vector field on [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] with isolated zeroes. If [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] has boundary, then we insist that [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] be pointing in the outward normal direction along the boundary. Then we have the formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_i \operatorname{index}_{x_i}(v) = \chi(M)\, }[/math]

where the sum of the indices is over all the isolated zeroes of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \chi(M) }[/math] is the Euler characteristic of [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]. A particularly useful corollary is when there is a non-vanishing vector field implying Euler characteristic 0.

The theorem was proven for two dimensions by Henri Poincaré[1] and later generalized to higher dimensions by Heinz Hopf.[2]

Significance

The Euler characteristic of a closed surface is a purely topological concept, whereas the index of a vector field is purely analytic. Thus, this theorem establishes a deep link between two seemingly unrelated areas of mathematics. It is perhaps as interesting that the proof of this theorem relies heavily on integration, and, in particular, Stokes' theorem, which states that the integral of the exterior derivative of a differential form is equal to the integral of that form over the boundary. In the special case of a manifold without boundary, this amounts to saying that the integral is 0. But by examining vector fields in a sufficiently small neighborhood of a source or sink, we see that sources and sinks contribute integer amounts (known as the index) to the total, and they must all sum to 0. This result may be considered[by whom?] one of the earliest of a whole series of theorems (e.g. Atiyah–Singer index theorem, De Rham's theorem, Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem) establishing deep relationships between geometric and analytical or physical concepts. They play an important role in the modern study of both fields.

Sketch of proof

- Embed M in some high-dimensional Euclidean space. (Use the Whitney embedding theorem.)

- Take a small neighborhood of M in that Euclidean space, Nε. Extend the vector field to this neighborhood so that it still has the same zeroes and the zeroes have the same indices. In addition, make sure that the extended vector field at the boundary of Nε is directed outwards.

- The sum of indices of the zeroes of the old (and new) vector field is equal to the degree of the Gauss map from the boundary of Nε to the (n–1)-dimensional sphere. Thus, the sum of the indices is independent of the actual vector field, and depends only on the manifold M. Technique: cut away all zeroes of the vector field with small neighborhoods. Then use the fact that the degree of a map from the boundary of an n-dimensional manifold to an (n–1)-dimensional sphere, that can be extended to the whole n-dimensional manifold, is zero.[citation needed]

- Finally, identify this sum of indices as the Euler characteristic of M. To do that, construct a very specific vector field on M using a triangulation of M for which it is clear that the sum of indices is equal to the Euler characteristic.

Generalization

It is still possible to define the index for a vector field with nonisolated zeroes. A construction of this index and the extension of Poincaré–Hopf theorem for vector fields with nonisolated zeroes is outlined in Section 1.1.2 of (Brasselet Seade).

See also

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Poincaré–Hopf theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/p110160

- Brasselet, Jean-Paul; Seade, José; Suwa, Tatsuo (2009). Vector fields on singular varieties. Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-05205-7.

|