Schramm's model of communication

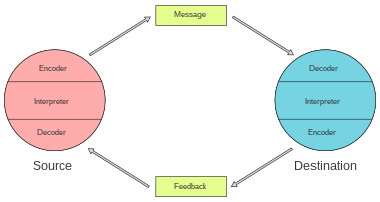

Schramm's model of communication is an early and influential model of communication. It was first published by Wilbur Schramm in 1954 and includes innovations over previous models, such as the inclusion of a feedback loop and the discussion of the role of fields of experience. For Schramm, communication is about sharing information or having a common attitude towards signs. His model is based on three basic components: a source, a destination, and a message. The process starts with an idea in the mind of the source. This idea is then encoded into a message using signs and sent to the destination. The destination needs to decode and interpret the signs to reconstruct the original idea. In response, they formulate their own message, encode it, and send it back as a form of feedback. Feedback is a key part of many forms of communication. It can be used to mitigate processes that may undermine successful communication, such as external noise or errors in the phases of encoding and decoding.

The success of communication also depends on the fields of experience of the participants. A field of experience includes past life experiences as well as attitudes and beliefs. It affects how the processes of encoding, decoding, and interpretation take place. For successful communication, the message has to be located in the overlap of the fields of experience of both participants. If the message is outside the receiver's field of experience, they are unable to connect it to the original idea. This is often the case when there are big cultural differences.

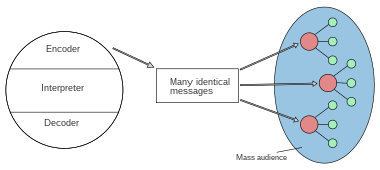

Schramm holds that the sender usually has some goal they wish to achieve through communication. He discusses the conditions that are needed to have this effect on the audience, such as gaining their attention and motivating them to act towards this goal. He also applies his model to mass communication. One difference from other forms of communication is that successful mass communication is more difficult since there is very little feedback. In the 1970s, Schramm proposed many revisions to his earlier model. They focus on additional factors that make communication more complex. An example is the relation between sender and receiver: it influences the goal of communication and the roles played by the participants.

Schramm's criticism of linear models of communication, which lack a feedback loop, has been very influential. One shortcoming of Schramm's model is that it assumes that the communicators take turns in exchanging information instead of sending messages simultaneously. Another objection is that Schramm conceives information and its meaning as preexisting entities rather than seeing communication as a process that creates meaning.

Background

Schramm's model of communication was published by Wilbur Schramm in 1954. It is one of the earliest interaction models of communication.[1][2][3] It was conceived as a response to and an improvement over earlier attempts in the form of linear transmission models, like the Shannon–Weaver model and Lasswell's model.[4][5] Models of communication are simplified presentations of the process of communication and try to explain it by discussing its main components and their relations.[6][7][8]

For Schramm, a central aspect of communication is that the participants "are trying to establish a 'commonness'" by sharing an idea or information.[9][10] In this regard, communication can be defined as "the sharing of an orientation toward a set of informational signs" and is based on a relation between the communicators.[11] So when a person calls the fire department to report a fire in their home, this is an attempt to share information about the fire. This sharing happens through messages.[9][10] For Schramm, messages are made up of signs. Each sign corresponds to some element in experience, like the sign "dog" which "stands for our generalized experience of dogs". This sign is meaningless for someone who has never experienced dogs before or who does not associate the sign with their experiences of dogs.[12][13]

The theories of psychologist Charles Osgood were a significant influence and inspired Schramm to formulate his model. According to Osgood, meaning is located not just in the message but also in the social context.[3] His psycholinguistic approach focuses on how external stimuli elicit internal responses in the form of interpretations. These responses mediate between the stimulus and its meaning.[14] Osgood's ideas influenced Schramm in two important ways: (1) he posited a field of shared experience acting as the background of communication and (2) he added the stages of encoding and decoding as internal responses to the process.[3] Because of these influences, some theorists refer to Schramm's model as the "Osgood–Schramm model".[2][5]

Most theorists identify Schramm's model with his 1954 book The process and effects of mass communication and present it as a reaction to earlier models developed in the late 1940s.[2][3][15] However, marketing scholar Jim Blythe argues that Schramm's model is of earlier origin and was already present in Schramm's 1949[lower-alpha 1] book Mass Communication.[16][17]

Overview and basic components

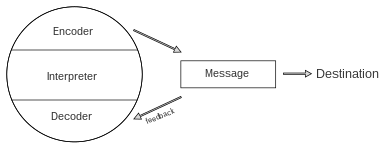

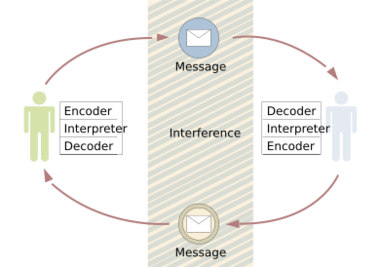

For Schramm, communication has in its most basic form three parts: a source, a message, and a destination. The source can be an individual or an organization, like a newspaper or a television station. The same is true for the destination.[18][10] The process starts in the sender's mind, where the message originates in the form of an idea. To share this information, the source needs to encode it first into symbolic form since the idea cannot be transmitted directly from mind to mind.[1][19][20] This can happen in various ways: the signs can be linguistic (like written or spoken words) or non-linguistic (like pictures, music, or animal sounds).[16] They are then transmitted through a channel, for example, as sounds for a face-to-face conversation, as ink on paper for a letter, or as electronic signals in the case of text messaging. At this stage, noise may interfere with the transmission and distort the message.[10][16] Once the message reaches the receiver, the reverse process of decoding is applied: the receiver attaches meaning to the signs according to their own field of experience. This way, they try to reconstruct the sender's original idea. The process continues when the receiver returns a new message as feedback to the original sender.[1][20]

The process of communication can fail in various ways. For example, the message may be distorted by external noise. But errors can also occur at the stages of encoding and decoding when the source does not use the correct signs or when the pattern of decoding does not match the pattern of encoding. A further problem is posed if the original information is faulty, to begin with. For effective communication, all these negative influences need to be avoided.[21][22]

Schramm's model is based on the Shannon–Weaver model. According to the Shannon–Weaver model, communication is an interaction of various components. A source translates a message into a signal using a transmitter. The signal is then sent through a channel to a receiver. The receiver translate the signal back into a message and makes it available to a destination. The steps of encoding and decoding in Schramm's model perform the same role as transmitter and receiver in the Shannon–Weaver model.[5][23][24] Because of its emphasis on communication as a circular process, the main focus of Schramm's model is on the behavior of senders and receivers. For this reason, it does not involve a detailed technical discussion of the channel and influences of noise, unlike the Shannon–Weaver model.[1][2][20]

Feedback

The role of feedback is one innovation of Schramm's model in comparison to earlier models.[3][25][16] Schramm sees communication as a dynamic interaction in which two participants exchange messages.[1][2][16] That means that the process of communication does not end in the receiver's mind. Instead, upon receiving a message, the communicator returns some feedback: they formulate a new message in the form of an idea, encode it, and convey it to the original sender, where the process starts anew.[2][5][20] Communication is an endless process in the sense that people constantly decode and interpret their environment to assign meaning to it and encode possible responses to it.[5][20]

Models without a feedback loop, like the Shannon–Weaver model and Lasswell's model, are called linear transmission models. They contrast with interaction models, also known as non-linear or circular transmission models.[6][26] Schramm rejects the idea of a passive audience present in linear models of communication. He argues instead that the audience should be understood as a full partner.[27] Feedback is a vital aspect of many forms of communication. It can be used to confirm that the message was received and to mitigate the influence of noise. For example, the message may get distorted on the way or the receiver may misinterpret it. In such cases, the feedback loop makes it possible to assess whether such errors occurred and, if so, repeat the message to ensure that it is understood correctly.[16]

Schramm also discusses another form of feedback that does not depend on the other person. This happens when the sender pays attention to their own message, for example, when reading through a letter one just wrote to check its style and tone.[28][25]

Field of experience

Another innovation of Schramm's model is the role of fields of experience.[13][11][16] A field of experience is a mental frame of reference.[29] It includes past life experiences as well as the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the communicators.[13][16][30] Each participant has their own field of experience. It determines how the processes of encoding, decoding, and interpretation take place.[20][30] For example, an American is unable to encode their message in Russian if they have never learned this language. And if a person from an indigenous tribe has never heard of an airplane then they are unable to accurately decode messages about airplanes.[13] The more the participants are alike, the more their fields of experience overlap. For communication to be successful, the message has to be located within both fields of experience, i.e. in their overlap.[13][20][30]

The bigger the cultural differences, the more difficult effective communication becomes. This is especially relevant for communication across national boundaries.[16][30] Blythe cites this lack of overlap as an example of failed communication in the case of foreign advertisements, which may appear incomprehensible or unintentionally humorous.[16] The lack of overlap can also happen for people within the same culture, for example, when an amateur tries to read specialist scientific literature. In some cases, such problems can be avoided if the sender is able to encode their message using an easy expression that is accessible to the destination.[20][12][13] The concept of a field of experience is similar to what later models refer to as social and cultural contexts.[4][31]

Conditions of successful communication

Communication is usually tied to some intended effect. So putting an advertisement in a newspaper, scolding a child, or engaging in a job interview are forms of communication directed at different goals. Communication is not always successful and the message may fail to achieve the intended effect.[32][33] Schramm lists four conditions of successful communication. The message must be designed (1) to gain the attention of the destination and (2) to be understandable to get the meaning across. Additionally, it must (3) arouse needs in the destination, and (4) suggest a way how these needs can be met.[34][35]

To get the attention of the audience, the message must be accessible to them. When talking, for example, one must talk loud enough to be heard. To ensure that the message is understandable, the sender must be aware of the field of experience of the audience in order to choose words and examples that are familiar to them.[12][34][36] Through the relation to the destination's needs, the message can unfold its effect by motivating them to respond.[37][38]

Depending on the message and the intended effect, it can address needs like security, status, or love. This aspect plays a central role in all forms of advertisement. A good knowledge of one's audience's character is required to understand which need to arouse and how to arouse it. This depends also on the specific situation and the circumstances, for example, whether the audience is in the right mood and whether the intended response is socially acceptable in the given situation. To unfold its effect, there has to be some form of action that the audience can perform to satisfy this need. There are usually many actions available. The sender may use the message to suggest the action that is most in tune with the effect they intend to provoke. For example, a political party may use a campaign event to spread fear of an external threat in order to arouse the audience's need for security. The party may then promise to eliminate this threat to get the audience to act in tune with its intended goal: to secure their votes.[39][40][41]

Application to mass communication

For mass communication, the source is usually not an individual but rather an organization like a newspaper or a broadcasting network. The basic steps like encoding and decoding are the same but they are not performed by a single person but by a group of people, like the employed reporters and editors. The destinations of mass communication are individual people, like the readers of a newspaper. The hallmark of mass communication is that the message reaches a very large number of people. This stands in contrast to face-to-face communication taking place between two or a small number of people. Another difference is that there is very little direct feedback in mass communication. For example, it happens very seldom that a viewer contacts a broadcast network or that a reader writes a letter to an editor. Feedback is here often more indirect: people may stop to buy a service or to view a program if they are not satisfied with it, usually without providing a reason to the sender for their decision. This lack of feedback makes effective communication more difficult since it is not directly obvious to the sender whether their message had the intended effect. This is one of the reasons why mass communication providers often conduct audience research. This way, they can obtain vital information about their target audience so they can formulate their messages accordingly.[42]

It is very difficult to predict the effects of mass communication since the effect differs a lot from person to person based on their personality, mood, and current situation. An additional factor in this regard is that the effects are not restricted to direct effects on the person receiving the message. Instead, they are also indirect: the receiver is part of a social environment and may share, criticize, and reflect on the message with the people in their environment.[44][45]

Later developments

Schramm proposed revisions to his model in the 1970s.[16][27] He explained that many developments in the field of communication studies since his first model had shown that communication is a very complex phenomenon. He agreed that his initial model was too simple to do justice to this complexity.[46][47] He tried to address these shortcomings by developing a relational model of communication. These changes were influenced by David Berlo's model of communication and its focus on the effects of communication. Berlo had argued that the goal of all communication is to influence the behavior of the audience.[48] Schramm's relational model focuses on the relation between sender and receiver. The relation includes the totality of the past experiences the communicators have had with each other. It can be based on past face-to-face contact with the other party, as when meeting a friend for dinner, but need not be, as would be the case when reading a newspaper article by a reporter one has never met. But even in this case, past experiences shape what the reader expects from the newspaper and what the reporter expects from the readership.[49]

For Schramm, the relation is a basic requirement of communication since communication is about sharing information or attitudes and, in this sense, being in tune with each other.[11][50] It determines many aspects of communication, like its goal, the roles played by the participants, and the expectations they bring to the exchange.[51] The goal is what the communicators intend to achieve by communicating. In the instructional context, the goal is to transmit information while performance arts are about entertaining the audience. The relation also affects the role of the participants. For instruction, this involves the roles of teacher and student. These roles determine how the participants are expected to contribute to the communicative goal. For example, teachers may share and explain information while students may listen and ask clarifying questions. As the background of communication, the relation also affects how the messages are interpreted. For example, seeing a person as an actor on a stage leads to one interpretation of their messages. But interacting with them during business negotiations results in a very different interpretation of the same messages.[52][53]

Influence and criticism

Schramm's model has been influential both for its criticism of linear transmission models and for its innovations in trying to overcome them. Schramm was one of the first scholars to challenge the Shannon–Weaver model of communication.[4] According to him, the shortcomming of the Shannon–Weaver model and other linear transmission models is that they assume that the communicative process ends when the message reaches its destination.[1][5][20] He terms them "bullet theories of communication" since communication is seen as a magic bullet that goes from active senders to passive receivers in the form of sending ideas to the receivers' mind.[54][55][56] Schramm rejects the idea that the audience is a passive receiver and assigns them a more active role: the audience respondes by generates a new message and sends it back to the original as a form of feedback. Many scholars have followed Schramm's criticisms of linear transmission models. They agree that communication is a dynamic exchange involving an active audience and feedback loops.[1][5][20] Schramm's other innovations have also been influential, like his concept of the field of experience and his development of relational models in his later work.[16][27][57]

A common criticism of Schramm's model focuses on the fact that it describes communication as a turn-based exchange of information. This means that there is no simultaneous messaging: first one participant sends a message, then the other conveys their own message as a form of feedback, later the first participant responds again, etc. However, these processes often happen simultaneously for many forms of communication.[2] For example, in face-to-face conversations like a first date, the listener usually uses facial expressions and body posture to signal their agreement or interest. This happens while the speaker is talking, the listener does not wait for the speaker to finish before engaging in this form of non-verbal communication.[7] This shortcoming of Schramm's model is addressed by so-called transaction models, which allow for simultaneous messaging. The weight of this objection depends on the type of communication analyzed. For some forms, like pen pals exchanging letters or instant messaging, disregarding simultaneous messages has little impact, but in other cases, it is an important factor.[2][7]

Another criticism of Schramm's model argues that, for Schramm, the information and its meaning exist prior to the communicative act. Communication itself is then just understood as an exchange of messages or meaning. This view is characteristic of transmission models but is rejected by constitutive models. Constitutive models hold that meaning does not exist before the communication but is created in the process. In this regard, the dialog acts as a cooperative process through which meaning is constructed.[1][16] Such an approach is proposed by Everett Rogers and Thomas Steinfatt. They elaborate Schramm's interactive approach and combine it with the assumption that the communicators create and share meaning with the goal of reaching a mutual understanding.[4] Similar approaches to communication focusing on the co-construction of meaning are presented by S. A. Deetz and G. Mantovani.[16]

A further limitation is that Schramm's model is restricted to communication between two parties. However, there are forms of group communication where more parties are involved.[4][58]

References

Notes

- ↑ Blythe cites it as 1948 but it is usually cited as 1949.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 176.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Steinberg 1995, p. 18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Bowman & Targowski 1987, pp. 21–34.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Liu, Volcic & Gallois 2014, p. 38.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Schwartz 2010, p. 52.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ruben 2001, Models Of Communication.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 UMN staff 2016, 1.2 The Communication Process.

- ↑ McQuail 2008, Models of communication.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Babe 2015, p. 128.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Schramm 1960, p. 3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ruben 2017, p. 12.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Babe 2015, p. 117.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Schramm 1960, p. 6.

- ↑ Heath & Bryant 2013, p. 101.

- ↑ Schramm 1960.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 Blythe 2009, pp. 177–80.

- ↑ Schramm 1949.

- ↑ Rogala & Bialowas 2016, p. 21.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, p. 4.

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 Moore 1994, pp. 90–1.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Chandler & Munday 2011b, noise.

- ↑ Chandler & Munday 2011d, Shannon and Weaver’s model.

- ↑ Shannon 1948, p. 381.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Schramm 1960, p. 9.

- ↑ Chandler & Munday 2011e, transmission models.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Narula 2006, pp. 11–44, 1. Basic Communication Models.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Naidu 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Dwyer 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Meng 2020, p. 120.

- ↑ Swift 2017, p. 195.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, p. 12.

- ↑ Babe 2015, p. 90.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Baker 2017, p. 401.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, p. 13.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, pp. 13–4.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, pp. 14–5.

- ↑ Babe 2015, p. 113.

- ↑ Babe 2015, pp. 113–114, 117.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, pp. 14–7.

- ↑

- Chandler & Munday 2011a, mass communication

- Moore 1994, pp. 90–1

- Page & Parnell 2020, p. 165

- Schramm 1960, pp. 18-9

- ↑ Schramm 1960, p. 21.

- ↑ Medoff & Kaye 2013, p. 4.

- ↑ Schramm 1960, pp. 20–1.

- ↑ Iosifidis 2011, p. 94.

- ↑ Schramm 1971, p. 6.

- ↑

- Narula 2006, pp. 11–44, 1. Basic Communication Models

- Schramm 1971, pp. 7–8

- Chandler & Munday 2011c, relational models

- Jandt 2010, p. 41

- Zaharna 2022, p. 70

- ↑

- Carney & Lymer 2022, p. 90

- Babe 2015, pp. 113–115

- Varey & Lewis 2000, p. 284

- Schramm 1971, pp. 14-5

- Chandler & Munday 2011c, relational models

- ↑ Schramm 1971, p. 14.

- ↑ Chandler & Munday 2011c, relational models.

- ↑ Babe 2015, pp. 115, 128.

- ↑ Schramm 1971, pp. 17–9, 34–8.

- ↑ Babe 2015, pp. 110.

- ↑ Paletz 1996, p. 259.

- ↑ Schramm 1971, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Schramm 1971, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Chandler & Munday 2011, group communication.

Sources

- Babe, Robert E. (2015) (in en). Wilbur Schramm and Noam Chomsky Meet Harold Innis: Media, Power, and Democracy. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0682-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=YAKeCAAAQBAJ.

- Baker, Michael J. (2017) (in en). Marketing Strategy and Management. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 401. ISBN 978-1-137-34213-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=DSRIEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA401.

- Blythe, Jim (2009) (in en). Key Concepts in Marketing. SAGE Publications. pp. 177–80. ISBN 978-1-84787-498-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=rPgQRbBLdYgC&pg=188.

- Bowman, J. P.; Targowski, A. S. (1987). "Modeling the Communication Process: The Map is Not the Territory". Journal of Business Communication 24 (4): 21–34. doi:10.1177/002194368702400402.

- Carney, William Wray; Lymer, Leah-Ann (2022) (in en). Fundamentals of Public Relations and Marketing Communications in Canada. University of Alberta. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-77212-651-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=9ue1EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA90.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011). "group communication" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011a). "mass communication" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011b). "noise" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011c). "relational models" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011d). "Shannon and Weaver’s model" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (2011e). "transmission models" (in en). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C.

- Dwyer, Judith (2012) (in en). Communication for Business and the Professions: Strategie s and Skills. Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4425-5055-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=xhHiBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA10.

- Heath, Robert L.; Bryant, Jennings (2013) (in en). Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-135-67706-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=xx_MG6BaDKEC&pg=PA101.

- Iosifidis, P. (2011) (in en). Global Media and Communication Policy: An International Perspective. Springer. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-230-34658-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=kaCHDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA94.

- Jandt, Fred Edmund (2010) (in en). An Introduction to Intercultural Communication: Identities in a Global Community. SAGE. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4129-7010-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=3nqUSY2C4wsC&pg=PA41.

- Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (2009) (in en). Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. SAGE Publications. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4129-5937-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=2veMwywplPUC&pg=PA176.

- Liu, Shuang; Volcic, Zala; Gallois, Cindy (2014) (in en). Introducing Intercultural Communication: Global Cultures and Contexts. SAGE. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4739-0912-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=QfSICwAAQBAJ&pg=PA38.

- McQuail, Denis (2008). "Models of communication". in Donsbach, Wolfgang (in en-us). The International Encyclopedia of Communication, 12 Volume Set. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3199-5. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/The+International+Encyclopedia+of+Communication%2C+12+Volume+Set-p-9781405131995.

- Medoff, Norman J.; Kaye, Barbara (2013) (in en). Electronic Media: Then, Now, and Later. Taylor & Francis. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-136-03041-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=mo5X6niXB_wC&pg=PT17.

- Meng, Xiangfei (2020) (in en). National Image: China's Communication of Cultural Symbols. Springer Nature. p. 120. ISBN 978-981-15-3147-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=b0HWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA120.

- Moore, David Mike (1994) (in en). Visual Literacy: A Spectrum of Visual Learning. Educational Technology. pp. 90–1. ISBN 978-0-87778-264-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=icMsdAGHQpEC&pg=PA90.

- Naidu, P. Ch Appala (2008) (in en). Feedback Methods and Student Performance. Discovery Publishing House. p. 23. ISBN 978-81-8356-284-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=sZQWMpiWy3IC&pg=PA23.

- Narula, Uma (2006). "1. Basic Communication Models" (in en). Handbook of Communication Models, Perspectives, Strategies. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 11–44. ISBN 978-81-269-0513-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=AuRyXwyAJ78C.

- Page, Janis Teruggi; Parnell, Lawrence J. (2020) (in en). Introduction to Public Relations: Strategic, Digital, and Socially Responsible Communication. SAGE Publications. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-5443-9202-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=RHjqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT165.

- Paletz, David L. (1996) (in en). Political Communication Research: Approaches, Studies, Assessments. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-56750-163-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=kWt8G2P59bIC&pg=PA259.

- Rogala, Anna; Bialowas, Sylwester (2016) (in en). Communication in Organizational Environments: Functions, Determinants and Areas of Influence. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-137-54703-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ok4iDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA21.

- Ruben, Brent D. (2017) (in en). Between Communication and Information. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-351-29471-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Fm5QDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA12.

- Ruben, Brent D. (2001). "Models Of Communication". Encyclopedia of Communication and Information. https://www.encyclopedia.com/media/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/models-communication.

- (in en) Mass communications. University of Illinois Press. 1949. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1950-02563-000.

- Schramm, Wilbur (1971). "The Nature of Communication between Humans" (in en). The Process and Effects of Mass Communication - Revised Edition. University of Illinois Press. pp. 3–53. ISBN 978-0-252-00197-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=112wAAAAIAAJ.

- Schramm, Wilbur (1960). "How communication works" (in en). The Process and Effects of Mass Communication. University of Illinois Press. pp. 3–26. https://books.google.com/books?id=z2aaAQAACAAJ.

- Schwartz, David (2010) (in en). Encyclopedia of Knowledge Management, Second Edition. IGI Global. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59904-932-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=K92eBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA52.

- Shannon, C. E. (July 1948). "A Mathematical Theory of Communication". Bell System Technical Journal 27 (3): 381. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

- Steinberg, S. (1995) (in en). Introduction to Communication Course Book 1: The Basics. Juta and Company Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7021-3649-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=VPs3kidEqXYC&pg=PA18.

- Swift, Jonathan (2017) (in en). Understanding Business in the Global Economy: A Multi-Level Relationship Approach. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-137-60380-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRxHEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA195.

- UMN staff (2016). "1.2 The Communication Process" (in en-us). Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. ISBN 978-1-946135-07-0. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/1-2-the-communication-process/.

- United States Naval Education and Training staff (1978) (in en). Journalist 1 & C.. Department of Defense, Department of the Navy, Naval Education and Training Command. p. 29. https://books.google.com/books?id=0GAirbhYrcwC&pg=PA29.

- Varey, Richard J.; Lewis, Barbara R. (2000) (in en). Internal Marketing: Directions for Management. Psychology Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-415-21317-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=onuBdFC4Q7wC&pg=PA284.

- Zaharna, R. S. (2022) (in en). Boundary Spanners of Humanity: Three Logics of Communications and Public Diplomacy for Global Collaboration. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780190930271. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSxTEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA70.

|