Biology:Communication

Communication (from Latin communicare, meaning "to share"or "to be in relation with")[1][2][3] is "an apparent answer to the painful divisions between self and other, private and public, and inner thought and outer word."[4] As this definition indicates, communication is difficult to define in a consistent manner,[5][6] because it is commonly used to refer to a wide range of different behaviors (broadly: "the transfer of information"[7]), or to limit what can be included in the category of communication (for example, requiring a "conscious intent" to persuade[8]). John Peters argues the difficulty of defining communication emerges from the fact that communication is both a universal phenomena (because everyone communicates), and a specific discipline of institutional academic study.[9]

One possible definition of communication is the act of developing meaning among entities or groups through the use of sufficiently mutually understood signs, symbols, and semiotic conventions.

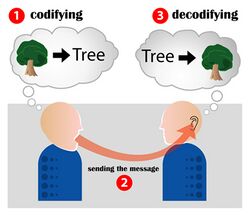

In Claude Shannon's and Warren Weaver's influential[10][11] model, human communication was imagined to function like a telephone or telegraph.[12] Accordingly, they conceptualized communication as involving discrete steps:

- The formation of communicative motivation or reason.

- Message composition (further internal or technical elaboration on what exactly to express).

- Message encoding (for example, into digital data, written text, speech, pictures, gestures and so on).

- Transmission of the encoded message as a sequence of signals using a specific channel or medium.

- Noise sources such as natural forces and in some cases human activity (both intentional and accidental) begin influencing the quality of signals propagating from the sender to one or more receivers.

- Reception of signals and reassembling of the encoded message from a sequence of received signals.

- Decoding of the reassembled encoded message.

- Interpretation and making sense of the presumed original message.

These elements are now understood to be substantially overlapping and recursive activities rather than steps in a sequence.[13] For example, communicative actions can commence before a communicator formulates a conscious attempt to do so,[14] as in the case of phatics; likewise, communicators modify their intentions and formulations of a message in response to real-time feedback (e.g., a change in facial expression).[15] Practices of decoding and interpretation are culturally enacted, not just by individuals (genre conventions, for instance, trigger anticipatory expectations for how a message is to be received), and receivers of any message operationalize their own frames of reference in interpretation.[16]

The scientific study of communication can be divided into:

- Information theory which studies the quantification, storage, and communication of information in general;

- Communication studies which concerns human communication;

- Biosemiotics which examines communication in and between living organisms in general.

- Biocommunication which exemplifies sign-mediated interactions in and between organisms of all domains of life, including viruses.

The channel of communication can be visual, auditory, tactile/haptic (e.g. Braille or other physical means), olfactory, electromagnetic, or biochemical. Human communication is unique for its extensive use of abstract language. Development of civilization has been closely linked with progress in telecommunication.

Types of Communication

Non-verbal communication

Nonverbal communication explains the processes of conveying a type of information in a form of non-linguistic representations. Examples of nonverbal communication include haptic communication, chronemic communication, gestures, body language, facial expressions, eye contact etc. Nonverbal communication also relates to the intent of a message. Examples of intent are voluntary, intentional movements like shaking a hand or winking, as well as involuntary, such as sweating.[17] Speech also contains nonverbal elements known as paralanguage, e.g. rhythm, intonation, tempo, and stress. It affects communication most at the subconscious level and establishes trust. Likewise, written texts include nonverbal elements such as handwriting style, the spatial arrangement of words and the use of emoticons to convey emotion.

Nonverbal communication demonstrates one of Paul Watzlawick's laws: you cannot not communicate. Once proximity has formed awareness, living creatures begin interpreting any signals received.[18] Some of the functions of nonverbal communication in humans are to complement and illustrate, to reinforce and emphasize, to replace and substitute, to control and regulate, and to contradict the denotative message.

Nonverbal cues are heavily relied on to express communication and to interpret others' communication and can replace or substitute verbal messages. However, non-verbal communication is ambiguous. When verbal messages contradict non-verbal messages, observation of non-verbal behaviour is relied on to judge another's attitudes and feelings, rather than assuming the truth of the verbal message alone.

There are several reasons as to why non-verbal communication plays a vital role in communication:

"Non-verbal communication is omnipresent."[19] They are included in every single communication act. To have total communication, all non-verbal channels such as the body, face, voice, appearance, touch, distance, timing, and other environmental forces must be engaged during face-to-face interaction. Written communication can also have non-verbal attributes. E-mails, web chats, and the social media have options to change text font colours, stationery, add emoticons, capitalization, and pictures in order to capture non-verbal cues into a verbal medium.[20]

"Non-verbal behaviours are multifunctional."[21] Many different non-verbal channels are engaged at the same time in communication acts and allow the chance for simultaneous messages to be sent and received.

"Non-verbal behaviours may form a universal language system."[21] Smiling, crying, pointing, caressing, and glaring are non-verbal behaviours that are used and understood by people regardless of nationality. Such non-verbal signals allow the most basic form of communication when verbal communication is not effective due to language barriers.

Verbal communication

Verbal communication is the spoken or written conveyance of a message. Human language can be defined as a system of symbols (sometimes known as lexemes) and the grammars (rules) by which the symbols are manipulated. The word "language" also refers to common properties of languages. Language learning normally occurs most intensively during human childhood. Most of the large number of human languages use patterns of sound or gesture for symbols which enable communication with others around them. Languages tend to share certain properties, although there are exceptions. Constructed languages such as Esperanto, programming languages, and various mathematical formalisms are not necessarily restricted to the properties shared by human languages.

As previously mentioned, language can be characterized as symbolic. Charles Ogden and I.A Richards developed The Triangle of Meaning model to explain the symbol (the relationship between a word), the referent (the thing it describes), and the meaning (the thought associated with the word and the thing).

The properties of language are governed by rules. Language follows phonological rules (sounds that appear in a language), syntactic rules (arrangement of words and punctuation in a sentence), semantic rules (the agreed upon meaning of words), and pragmatic rules (meaning derived upon context).

The meanings that are attached to words can be literal, or otherwise known as denotative; relating to the topic being discussed, or, the meanings take context and relationships into account, otherwise known as connotative; relating to the feelings, history, and power dynamics of the communicators.[22]

Contrary to popular belief, signed languages of the world (e.g., American Sign Language) are considered to be verbal communication because their sign vocabulary, grammar, and other linguistic structures abide by all the necessary classifications as spoken languages. There are however, nonverbal elements to signed languages, such as the speed, intensity, and size of signs that are made. A signer might sign "yes" in response to a question, or they might sign a sarcastic-large slow yes to convey a different nonverbal meaning. The sign yes is the verbal message while the other movements add nonverbal meaning to the message.

Written communication and its historical development

Over time the forms of and ideas about communication have evolved through the continuing progression of technology. Advances include communications psychology and media psychology, an emerging field of study.

The progression of written communication can be divided into three "information communication revolutions":[23]

- Written communication first emerged through the use of pictographs. The pictograms were made in stone, hence written communication was not yet mobile. Pictograms began to develop standardized and simplified forms.

- The next step occurred when writing began to appear on paper, papyrus, clay, wax, and other media with commonly shared writing systems, leading to adaptable alphabets. Communication became mobile.

- The final stage is characterized by the transfer of information through controlled waves of electromagnetic radiation (i.e., radio, microwave, infrared) and other electronic signals.

Communication is thus a process by which meaning is assigned and conveyed in an attempt to create shared understanding. Gregory Bateson called it "the replication of tautologies in the universe.[24] This process, which requires a vast repertoire of skills in interpersonal processing, listening, observing, speaking, questioning, analyzing, gestures, and evaluating enables collaboration and cooperation.[25][full citation needed]

Communication models

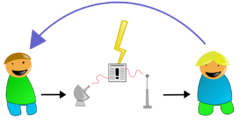

The first major model for communication was introduced by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver for Bell Laboratories in 1949[26] The original model was designed to mirror the functioning of radio and telephone technologies. Their initial model consisted of three primary parts: sender, channel, and receiver. The sender was the part of a telephone a person spoke into, the channel was the telephone itself, and the receiver was the part of the phone where one could hear the other person. Shannon and Weaver also recognized that often there is static that interferes with one listening to a telephone conversation, which they deemed noise.

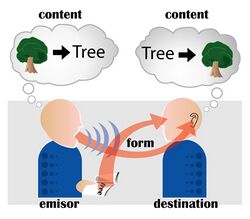

In a simple model, often referred to as the transmission model or standard view of communication, information or content (e.g. a message in natural language) is sent in some form (as spoken language) from an emitter (emisor in the picture)/sender/encoder to a destination/receiver/decoder. This common conception of communication simply views communication as a means of sending and receiving information. The strengths of this model are simplicity, generality, and quantifiability. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver structured this model based on the following elements:

- An information source, which produces a message.

- A transmitter, which encodes the message into signals.

- A channel, to which signals are adapted for transmission.

- A noise source, which distorts the signal while it propagates through the channel.

- A receiver, which 'decodes' (reconstructs) the message from the signal.

- A destination, where the message arrives.

Shannon and Weaver argued that there were three levels of problems for communication within this theory.

- The technical problem: how accurately can the message be transmitted?

- The semantic problem: how precisely is the meaning conveyed?

- The effectiveness problem: how effectively does the received meaning affect behavior?

Daniel Chandler[27] critiques the transmission model by stating:

- It assumes communicators are isolated individuals.

- No allowance for differing purposes.

- No allowance for differing interpretations.

- No allowance for unequal power relations.

- No allowance for situational contexts.

In 1960, David Berlo expanded on Shannon and Weaver's (1949) linear model of communication and created the SMCR Model of Communication.[28] The Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver Model of communication separated the model into clear parts and has been expanded upon by other scholars.

Communication is usually described along a few major dimensions: message (what type of things are communicated), source/emisor/sender/encoder (from whom), form (in which form), channel (through which medium), destination/receiver/target/decoder (to whom). Wilbur Schram (1954) also indicated that we should also examine the impact that a message has (both desired and undesired) on the target of the message.[29] Between parties, communication includes acts that confer knowledge and experiences, give advice and commands, and ask questions. These acts may take many forms, in one of the various manners of communication. The form depends on the abilities of the group communicating. Together, communication content and form make messages that are sent towards a destination. The target can be oneself, another person or being, another entity (such as a corporation or group of beings).

Communication can be seen as processes of information transmission with three levels of semiotic rules:

- Pragmatic (concerned with the relations between signs/expressions and their users).

- Semantic (study of relationships between signs and symbols and what they represent).

- Syntactic (formal properties of signs and symbols).

Therefore, communication is social interaction where at least two interacting agents share a common set of signs and a common set of semiotic rules. This commonly held rule in some sense ignores autocommunication, including intrapersonal communication via diaries or self-talk, both secondary phenomena that followed the primary acquisition of communicative competences within social interactions.

In light of these weaknesses, Barnlund (2008) proposed a transactional model of communication.[30] The basic premise of the transactional model of communication is that individuals are simultaneously engaging in the sending and receiving of messages.

In a slightly more complex form a sender and a receiver are linked reciprocally. This second attitude of communication, referred to as the constitutive model or constructionist view, focuses on how an individual communicates as the determining factor of the way the message will be interpreted. Communication is viewed as a conduit; a passage in which information travels from one individual to another and this information becomes separate from the communication itself. A particular instance of communication is called a speech act. The sender's personal filters and the receiver's personal filters may vary depending upon different regional traditions, cultures, or gender; which may alter the intended meaning of message contents. In the presence of "communication noise" on the transmission channel (air, in this case), reception and decoding of content may be faulty, and thus the speech act may not achieve the desired effect. One problem with this encode-transmit-receive-decode model is that the processes of encoding and decoding imply that the sender and receiver each possess something that functions as a codebook, and that these two code books are, at the very least, similar if not identical. Although something like code books is implied by the model, they are nowhere represented in the model, which creates many conceptual difficulties.

Theories of coregulation describe communication as a creative and dynamic continuous process, rather than a discrete exchange of information. Canadian media scholar Harold Innis had the theory that people use different types of media to communicate and which one they choose to use will offer different possibilities for the shape and durability of society.[31][page needed] His famous example of this is using ancient Egypt and looking at the ways they built themselves out of media with very different properties stone and papyrus. Papyrus is what he called 'Space Binding'. it made possible the transmission of written orders across space, empires and enables the waging of distant military campaigns and colonial administration. The other is stone and 'Time Binding', through the construction of temples and the pyramids can sustain their authority generation to generation, through this media they can change and shape communication in their society.[31][page needed]

As academic discipline with distinct fields of study

The academic discipline that deals with processes of human communication is communication studies. The discipline encompasses a range of topics, from face-to-face conversation to mass media outlets such as television broadcasting. Communication studies also examines how messages are interpreted through the political, cultural, economic, semiotic, hermeneutic, and social dimensions of their contexts. Statistics, as a quantitative approach to communication science, has also been incorporated into research on communication science in order to help substantiate claims.[32]

Organizational communication

Business communication is used for a wide variety of activities including, but not limited to: strategic communications planning, media relations, internal communications, public relations (which can include social media, broadcast and written communications, and more), brand management, reputation management, speech-writing, customer-client relations, and internal/employee communications.

Companies with limited resources may choose to engage in only a few of these activities, while larger organizations may employ a full spectrum of communications. Since it is relatively difficult to develop such a broad range of skills, communications professionals often specialize in one or two of these areas but usually have at least a working knowledge of most of them. By far, the most important qualifications communications professionals must possess are excellent writing ability, good 'people' skills, and the capacity to think critically and strategically.

Business communication could also refer to the style of communication within a given corporate entity (i.e. email conversation styles, or internal communication styles).

Political communication

Communication is one of the most relevant tools in political strategies, including persuasion and propaganda. In mass media research and online media research, the effort of the strategist is that of getting a precise decoding, avoiding "message reactance", that is, message refusal. The reaction to a message is referred also in terms of approach to a message, as follows:

- In "radical reading" the audience rejects the meanings, values, and viewpoints built into the text by its makers. Effect: message refusal.

- In "dominant reading", the audience accepts the meanings, values, and viewpoints built into the text by its makers. Effect: message acceptance.

- In "subordinate reading" the audience accepts, by and large, the meanings, values, and worldview built into the text by its makers. Effect: obey to the message.[33]

Holistic approaches are used by communication campaign leaders and communication strategists in order to examine all the options, "actors" and channels that can generate change in the semiotic landscape, that is, change in perceptions, change in credibility, change in the "memetic background", change in the image of movements, of candidates, players and managers as perceived by key influencers that can have a role in generating the desired "end-state".

The modern political communication field is highly influenced by the framework and practices of "information operations" doctrines that derive their nature from strategic and military studies. According to this view, what is really relevant is the concept of acting on the Information Environment. The information environment is the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that collect, process, disseminate, or act on information. This environment consists of three interrelated dimensions, which continuously interact with individuals, organizations, and systems. These dimensions are known as physical, informational, and cognitive.[34]

Interpersonal communication

In simple terms, interpersonal communication is the communication between one person and another (or others). It is often referred to as face-to-face communication between two (or more) people. Both verbal and nonverbal communication, or body language, play a part in how one person understands another, and attribute to one's own soft skills. In verbal interpersonal communication there are two types of messages being sent: a content message and a relational message. Content messages are messages about the topic at hand and relational messages are messages about the relationship itself.[35] This means that relational messages come across in how one says something and it demonstrates a person's feelings, whether positive or negative, towards the individual they are talking to, indicating not only how they feel about the topic at hand, but also how they feel about their relationship with the other individual.[35]

There are many different aspects of interpersonal communication including:

- Audiovisual Perception of Communication Problems.[36] The concept follows the idea that our words change what form they take based on the stress level or urgency of the situation. It also explores the concept that stuttering during speech shows the audience that there is a problem or that the situation is more stressful.

- The Attachment Theory.[37] This is the combined work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991) This theory follows the relationships that builds between a mother and child, and the impact it has on their relationships with others.

- Emotional Intelligence and Triggers.[38] Emotional Intelligence focuses on the ability to monitor ones own emotions as well as those of others. Emotional Triggers focus on events or people that tend to set off intense, emotional reactions within individuals.

- Attribution Theory.[39] This is the study of how individuals explain what causes different events and behaviors.

- The Power of Words (Verbal communications).[40] Verbal communication focuses heavily on the power of words, and how those words are said. It takes into consideration tone, volume, and choice of words.

- Nonverbal Communication. It focuses heavily on the setting that the words are conveyed in, as well as the physical tone of the words.

- Ethics in Personal Relations.[41] It is about a space of mutual responsibility between two individuals, it's about giving and receiving in a relationship. This theory is explored by Dawn J. Lipthrott in the article What IS Relationship? What is Ethical Partnership?

- Deception in Communication.[42] This concept goes into that everyone lies, and how this can impact relationships. This theory is explored by James Hearn in his article Interpersonal Deception Theory: Ten Lessons for Negotiators.

- Conflict in Couples.[43] This focuses on the impact that social media has on relationships, as well as how to communicate through conflict. This theory is explored by Amanda Lenhart and Maeve Duggan in their paper Couples, the Internet, and Social Media.

Family communication

Family communication is the study of the communication perspective in a broadly defined family, with intimacy and trusting relationship.[44] The main goal of family communication is to understand the interactions of family and the pattern of behaviors of family members in different circumstances. Open and honest communication creates an atmosphere that allows family members to express their differences as well as love and admiration for one another. It also helps to understand the feelings of one another.

Family communication study looks at topics such as family rules, family roles or family dialectics and how those factors could affect the communication between family members. Researchers develop theories to understand communication behaviors. Family communication study also digs deep into certain time periods of family life such as marriage, parenthood or divorce and how communication stands in those situations. It is important for family members to understand communication as a trusted way which leads to a well constructed family.

Barriers to effectiveness

Barriers to effective communication can retard or distort the message or intention of the message being conveyed. This may result in failure of the communication process or cause an effect that is undesirable. These include filtering, selective perception, information overload, emotions, language, silence, communication apprehension, gender differences and political correctness.[45]

This also includes a lack of expressing "knowledge-appropriate" communication, which occurs when a person uses ambiguous or complex legal words, medical jargon, or descriptions of a situation or environment that is not understood by the recipient.

- Physical barriers – Physical barriers are often due to the nature of the environment. An example of this is the natural barrier which exists when workers are located in different buildings or on different sites. Likewise, poor or outdated equipment, particularly the failure of management to introduce new technology, may also cause problems. Staff shortages are another factor which frequently causes communication difficulties for an organization.

- System design – System design faults refer to problems with the structures or systems in place in an organization. Examples might include an organizational structure which is unclear and therefore makes it confusing to know whom to communicate with. Other examples could be inefficient or inappropriate information systems, a lack of supervision or training, and a lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities which can lead to staff being uncertain about what is expected of them.

- Attitudinal barriers– Attitudinal barriers come about as a result of problems with staff in an organization. These may be brought about, for example, by such factors as poor management, lack of consultation with employees, personality conflicts which can result in people delaying or refusing to communicate, the personal attitudes of individual employees which may be due to lack of motivation or dissatisfaction at work, brought about by insufficient training to enable them to carry out particular tasks, or simply resistance to change due to entrenched attitudes and ideas.[citation needed]

- Ambiguity of words/phrases – Words sounding the same but having different meaning can convey a different meaning altogether. Hence the communicator must ensure that the receiver receives the same meaning. It is better if such words are avoided by using alternatives whenever possible.

- Individual linguistic ability – The use of jargon, difficult or inappropriate words in communication can prevent the recipients from understanding the message. Poorly explained or misunderstood messages can also result in confusion. However, research in communication has shown that confusion can lend legitimacy to research when persuasion fails.[46][47]

- Physiological barriers – These may result from individuals' personal discomfort, caused—for example—by ill health, poor eyesight or hearing difficulties.

- Bypassing – This happens when the communicators (the sender and the receiver) do not attach the same symbolic meanings to their words. It is when the sender is expressing a thought or a word but the receiver gives it a different meaning. For example- ASAP, Rest room.

- Technological multi-tasking and absorbency – With a rapid increase in technologically-driven communication in the past several decades, individuals are increasingly faced with condensed communication in the form of e-mail, text, and social updates. This has, in turn, led to a notable change in the way younger generations communicate and perceive their own self-efficacy to communicate and connect with others. With the ever-constant presence of another "world" in one's pocket, individuals are multi-tasking both physically and cognitively as constant reminders of something else happening somewhere else bombard them. Though perhaps too new an advancement to yet see long-term effects, this is a notion currently explored by such figures as Sherry Turkle.[48]

- Fear of being criticized – This is a major factor that prevents good communication. If we exercise simple practices to improve our communication skill, we can become effective communicators. For example, read an article from the newspaper or collect some news from the television and present it in front of the mirror. This will not only boost your confidence but also improve your language and vocabulary.

- Gender barriers – Most communicators whether aware or not, often have a set agenda. This is very notable among the different genders. For example, many women are found to be more critical when addressing conflict. It's also been noted that men are more likely than women to withdraw from conflict.[49]

Noise

In any communication model, noise is interference with the decoding of messages sent over the channel by an encoder. There are many examples of noise:

- Environmental noise. Noise that physically disrupts communication, such as standing next to loud speakers at a party, or the noise from a construction site next to a classroom making it difficult to hear the professor.

- Physiological-impairment noise. Physical maladies that prevent effective communication, such as actual deafness or blindness preventing messages from being received as they were intended.

- Semantic noise. Different interpretations of the meanings of certain words. For example, the word "weed" can be interpreted as an undesirable plant in a yard, or as a euphemism for marijuana.

- Syntactical noise. Mistakes in grammar can disrupt communication, such as abrupt changes in verb tense during a sentence.

- Organizational noise. Poorly structured communication can prevent the receiver from accurate interpretation. For example, unclear and badly stated directions can make the receiver even more lost.

- Cultural noise. Stereotypical assumptions can cause misunderstandings, such as unintentionally offending a non-Christian person by wishing them a "Merry Christmas".

- Psychological noise. Certain attitudes can also make communication difficult. For instance, great anger or sadness may cause someone to lose focus on the present moment. Disorders such as autism may also severely hamper effective communication.[50]

To face communication noise, redundancy and acknowledgement must often be used. Acknowledgements are messages from the addressee informing the originator that his/her communication has been received and is understood.[51] Message repetition and feedback about message received are necessary in the presence of noise to reduce the probability of misunderstanding. The act of disambiguation regards the attempt of reducing noise and wrong interpretations, when the semantic value or meaning of a sign can be subject to noise, or in presence of multiple meanings, which makes the sense-making difficult. Disambiguation attempts to decrease the likelihood of misunderstanding. This is also a fundamental skill in communication processes activated by counselors, psychotherapists, interpreters, and in coaching sessions based on colloquium. In Information Technology, the disambiguation process and the automatic disambiguation of meanings of words and sentences has also been an interest and concern since the earliest days of computer treatment of language.[52]

Cultural aspects

Cultural differences exist within countries (tribal/regional differences, dialects and so on), between religious groups and in organisations or at an organisational level – where companies, teams and units may have different expectations, norms and idiolects. Families and family groups may also experience the effect of cultural barriers to communication within and between different family members or groups. For example: words, colours and symbols have different meanings in different cultures. In most parts of the world, nodding your head means agreement, shaking your head means "no", but this is not true everywhere.[53]

Communication to a great extent is influenced by culture and cultural variables.[54][55][56][57] Understanding cultural aspects of communication refers to having knowledge of different cultures in order to communicate effectively with cross culture people. Cultural aspects of communication are of great relevance in today's world which is now a global village, thanks to globalisation. Cultural aspects of communication are the cultural differences which influence communication across borders.

- Verbal communication refers to a form of communication which uses spoken and written words for expressing and transferring views and ideas. Language is the most important tool of verbal communication. Countries have different languages. A knowledge of languages of different countries can improve cross-cultural understanding.

- Non-verbal communication is a very wide concept and it includes all the other forms of communication which do not use written or spoken words. Non verbal communication takes the following forms:

- Paralinguistics are the elements other than language where the voice is involved in communication and includes tones, pitch, vocal cues etc. It also includes sounds from throat and all these are greatly influenced by cultural differences across borders.

- Proxemics deals with the concept of the space element in communication. Proxemics explains four zones of spaces, namely intimate, personal, social and public. This concept differs from culture to culture as the permissible space varies in different countries.

- Artifactics studies the non verbal signals or communication which emerges from personal accessories such as the dress or fashion accessories worn and it varies with culture as people of different countries follow different dress codes.

- Chronemics deals with the time aspects of communication and also includes the importance given to time. Some issues explaining this concept are pauses, silences and response lag during an interaction. This aspect of communication is also influenced by cultural differences as it is well known that there is a great difference in the value given by different cultures to time.

- Kinesics mainly deals with body language such as postures, gestures, head nods, leg movements, etc. In different countries, the same gestures and postures are used to convey different messages. Sometimes even a particular kinesic indicating something good in a country may have a negative meaning in another culture.

So in order to have an effective communication across the world it is desirable to have a knowledge of cultural variables effecting communication.

According to Michael Walsh and Ghil'ad Zuckermann, Western conversational interaction is typically "dyadic", between two particular people, where eye contact is important and the speaker controls the interaction; and "contained" in a relatively short, defined time frame. However, traditional Aboriginal conversational interaction is "communal", broadcast to many people, eye contact is not important, the listener controls the interaction; and "continuous", spread over a longer, indefinite time frame.[58][59]

Nonhuman

Every information exchange between living organisms — i.e. transmission of signals that involve a living sender and receiver can be considered a form of communication; and even primitive creatures such as corals are competent to communicate. Nonhuman communication also include cell signaling, cellular communication, and chemical transmissions between primitive organisms like bacteria and within the plant and fungal kingdoms.

Animals

The broad field of animal communication encompasses most of the issues in ethology. Animal communication can be defined as any behavior of one animal that affects the current or future behavior of another animal. The study of animal communication, called zoo semiotics (distinguishable from anthroposemiotics, the study of human communication) has played an important part in the development of ethology, sociobiology, and the study of animal cognition. Animal communication, and indeed the understanding of the animal world in general, is a rapidly growing field, and even in the 21st century so far, a great share of prior understanding related to diverse fields such as personal symbolic name use, animal emotions, animal culture and learning, and even sexual conduct, long thought to be well understood, has been revolutionized.

Plants and fungi

Communication is observed within the plant organism, i.e. within plant cells and between plant cells, between plants of the same or related species, and between plants and non-plant organisms, especially in the root zone. Plant roots communicate with rhizome bacteria, fungi, and insects within the soil. Recent research has shown that most of the microorganism plant communication processes are neuron-like.[60] Plants also communicate via volatiles when exposed to herbivory attack behavior, thus warning neighboring plants.[61] In parallel they produce other volatiles to attract parasites which attack these herbivores.

Fungi communicate to coordinate and organize their growth and development such as the formation of Marcelia and fruiting bodies. Fungi communicate with their own and related species as well as with non fungal organisms in a great variety of symbiotic interactions, especially with bacteria, unicellular eukaryote, plants and insects through biochemicals of biotic origin. The biochemicals trigger the fungal organism to react in a specific manner, while if the same chemical molecules are not part of biotic messages, they do not trigger the fungal organism to react. This implies that fungal organisms can differentiate between molecules taking part in biotic messages and similar molecules being irrelevant in the situation. So far five different primary signalling molecules are known to coordinate different behavioral patterns such as filamentation, mating, growth, and pathogenicity. Behavioral coordination and production of signaling substances is achieved through interpretation processes that enables the organism to differ between self or non-self, a biotic indicator, biotic message from similar, related, or non-related species, and even filter out "noise", i.e. similar molecules without biotic content.

Bacteria quorum sensing

Communication is not a tool used only by humans, plants and animals, but it is also used by microorganisms like bacteria. The process is called quorum sensing. Through quorum sensing, bacteria can sense the density of cells, and regulate gene expression accordingly. This can be seen in both gram positive and gram negative bacteria. This was first observed by Fuqua et al. in marine microorganisms like V. harveyi and V. fischeri.[62]

See also

- 21st century skills

- Advice

- Augmentative and alternative communication

- Bias-free communication

- Communication rights

- Context as Other Minds

- Cross-cultural communication

- Data transmission

- Error detection and correction

- Human communication

- Information engineering

- Inter mirifica

- Intercultural communication

- Ishin-denshin

- Group dynamics

- Language

- Mass communication

- Proactive communications

- Sign system

- Signal

- Small talk

- SPEAKING

- Telepathy

- Understanding

References

- ↑ Cobley, Paul (2008-06-05), Donsbach, Wolfgang, ed. (in en), Communication: Definitions and Concepts, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. wbiecc071, doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc071, ISBN 978-1-4051-8640-7, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc071, retrieved 2021-07-20

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "communication". Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/?term=communication. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ "What Is Communication?". https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/an-introduction-to-group-communication/s03-02-what-is-communication.html#:~:text=Defining%20Communication,(1967).&text=CommunicationThe%20process%20of%20understanding,of%20understanding%20and%20sharing%20meaning..

- ↑ Peters, John Durham (1999). Speaking into the air : a history of the idea of communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2. ISBN 0-226-66276-4. OCLC 40452957. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/40452957.

- ↑ Dance, Frank E. X. (1970-06-01). "The "Concept" of Communication" (in en). Journal of Communication 20 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1970.tb00877.x. ISSN 0021-9916. https://academic.oup.com/joc/article/20/2/201-210/4560917.

- ↑ Craig, Robert T. (1999). "Communication Theory as a Field" (in en). Communication Theory 9 (2): 119–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1999.tb00355.x. https://academic.oup.com/ct/article/9/2/119-161/4201776.

- ↑ Littlejohn, Stephen; Foss, Karen (2009), Definitions of Communication, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 296–299, doi:10.4135/9781412959384, ISBN 9781412959377, https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/communicationtheory/n108.xml, retrieved 2021-07-20

- ↑ Miller, Gerald R. (1966-06-01). "On Defining Communication: Another Stab". Journal of Communication 16 (2): 88–98. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1966.tb00020.x. ISSN 0021-9916. PMID 5941548. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1966.tb00020.x.

- ↑ Peters, John Durham (1986). "Institutional Sources of Intellectual Poverty in Communication Research" (in en). Communication Research 13 (4): 527–559. doi:10.1177/009365086013004002. ISSN 0093-6502. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/009365086013004002.

- ↑ Fiske, John (1982): Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge

- ↑ Chandler, Daniel (18 September 1995). "The Transmission Model of Communication". http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/short/trans.html?LMCL=xbWw8Z&LMCL=RcvMrF.

- ↑ Shannon, Claude E. & Warren Weaver (1949). A Mathematical Model of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press

- ↑ Reddy, Michael J. (1979). "The Conduit Metaphor -- A Case of Frame Conflict in our Language about Language." In Metaphor and Thought, Andrew Ortony, ed. Cambridge UP: 284-324.

- ↑ Cooper, Marilyn M. (2019). The Animal Who Writes. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 127–156. ISBN 978-0-8229-6579-4.

- ↑ Rommetveit, Ragnar (1974). On Message Structure: A Framework for the Study of Language and Communication. London: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-73295-8.

- ↑ Witte, Stephen P. (1992). "Context, Text, Intertext: Toward a Constructivist Semiotic of Writing". Written Communication 9 (2): 237–308. doi:10.1177/0741088392009002003.

- ↑ "Types of Body Language". http://www.simplybodylanguage.com/types-of-body-language.html.

- ↑ Wazlawick, Paul (1970's) opus

- ↑ (Burgoon, J., Guerrero, L., Floyd, K., (2010). Nonverbal Communication, Taylor & Francis. p. 3 )

- ↑ Martin-Rubió, Xavier (2018-09-30) (in en). Contextualising English as a Lingua Franca: From Data to Insights. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-1696-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=SupwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA9.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 (Burgoon et al., p. 4)

- ↑ Ferguson, Sherry Devereaux; Lennox-Terrion, Jenepher; Ahmed, Rukhsana; Jaya, Peruvemba (2014). Communication in Everyday Life: Personal and Professional Contexts. Canada: Oxford University Press. pp. 464. ISBN 9780195449280. https://books.google.com/books?id=HZFXngEACAAJ.

- ↑ Xin Li. "Complexity Theory – the Holy Grail of 21st Century". Lane Dept of CSEE, West Virginia University. http://www.csee.wvu.edu/~xinl/complexity.html.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory (1960). Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

- ↑ "communication". The office of superintendent of Public Instruction. Washington.

- ↑ Shannon, C.E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press

- ↑ Daniel Chandler, "The Transmission Model of Communication", Aber.ac.uk

- ↑ Berlo, D.K. (1960). The process of communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- ↑ Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of communication (pp. 3–26). Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ Barnlund, D.C. (2008). A transactional model of communication. In. C.D. Mortensen (Eds.), Communication theory (2nd ed., pp. 47–57). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Wark, McKenzie (1997). The Virtual Republic. Allen & Unwin, St Leonards.

- ↑ Hayes, Andrew F. (31 May 2005). Statistical Methods for Communication Science. Taylor & Francis. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781410613707. https://books.google.com/books?id=YQ5Yb3z5H1UC.

- ↑ Danesi, Marcel (2009), Dictionary of Media and Communications. M.E.Sharpe, Armonk, New York.

- ↑ "Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. Army (2012). Information Operations. Joint Publication 3-13. Joint Doctrine Support Division, 116 Lake View Parkway, Suffolk, VA.". http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_13.pdf.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Trenholm, Sarah; Jensen, Arthur (2013). Interpersonal Communication Seventh Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 360–361.

- ↑ Barkhuysen, P., Krahmer, E., Swerts, M., (2004) Audiovisual Perception of Communication Problems, ISCA Archive http://www.isca-speech.org/archive

- ↑ Bretherton, I., (1992) The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, Developmental Psychology, 28, 759-775

- ↑ Mazza, J., Emotional Triggers, MABC, CPC

- ↑ Bertram, M., (2004) How the Mind Explains Behavior: Folk Explanations, Meaning, and Social Interaction, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-13445-3

- ↑ "Listening". http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/a-primer-on-communication-studies/s05-listening.html.

- ↑ Lipthrott, D., What IS Relationship? What is Ethical Partnership?

- ↑ Hearn, J., (2006) Interpersonal Deception Theory: Ten Lessons for Negotiators

- ↑ Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., (2014) Couples, the Internet, and Social Media

- ↑ Turner, L.H., & West, R.L. (2013). Perspectives on family communication. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Robbins, S., Judge, T., Millett, B., & Boyle, M. (2011). Organisational Behaviour. 6th ed. Pearson, French's Forest, NSW pp. 315–317.

- ↑ What Should Be Included in a Project Plan. Retrieved December 18, 2009

- ↑ J. Scott Armstrong (1980). "Bafflegab Pays". Psychology Today: 12. http://qbox.wharton.upenn.edu/documents/mktg/research/Bafflegab%20Pays.pdf.

- ↑ "Technology can sometimes hinder communication, TR staffers observe - The Collegian" (in en-US). 2012-10-09. http://collegian.tccd.edu/?p=3851.

- ↑ Bailey, Sandra (2009). "Couple Relationships: Communication and Conflict Resolution". MSU Extension 17: 2. http://store.msuextension.org/publications/HomeHealthandFamily/MT200917HR.pdf. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ↑ Roy M. Berko, et al., Communicating. 11th ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc., 2010) 9–12

- ↑ North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Nato Standardization Agency AAP-6 – Glossary of terms and definitions, p. 43.

- ↑ Nancy Ide, Jean Véronis. "Word Sense Disambiguation: The State of the Art", Computational Linguistics, 24(1), 1998, pp. 1–40.

- ↑ Nageshwar Rao, Rajendra P. Das, Communication skills, Himalaya Publishing House, 9789350516669, p. 48

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://expertscolumn.com/content/communication-and-cognitive-components-culture.

- ↑ "Incorrect Link to Beyond Intractability Essay". Beyond Intractability. 2017-04-18. http://www.beyondintractability.org/bi-essay/cross-cultural-communication.

- ↑ "Important Components of Cross-Cultural Communication Essay". http://www.studymode.com/essays/Important-Components-Of-Cross-Cultural-Communication-595745.html.

- ↑ "Portable Document Format (PDF)". http://www.ijdesign.org/ojs/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/313/155.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2015), Engaging – A Guide to Interacting Respectfully and Reciprocally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, and their Arts Practices and Intellectual Property, Australian Government: Indigenous Culture Support, p. 12, https://arts.adelaide.edu.au/linguistics/guide.pdf, retrieved 25 June 2016

- ↑ Walsh, Michael (1997), Cross cultural communication problems in Aboriginal Australia, Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit, pp. 7–9, ISBN 9780731528745, https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/47329, retrieved 25 June 2016

- ↑ Baluska, F.; Marcuso, Stefano; Volkmann, Dieter (2006). Communication in plants: neuronal aspects of plant life. Taylor & Francis US. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-540-28475-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=IH9N4SKWTokC&pg=PA19. "...the emergence of plant neurobiology as the most recent area of plant sciences."

- ↑ Ian T. Baldwin; Jack C. Schultz (1983). "Rapid Changes in Tree Leaf Chemistry Induced by Damage: Evidence for Communication Between Plants". Science 221 (4607): 277–279. doi:10.1126/science.221.4607.277. PMID 17815197. Bibcode: 1983Sci...221..277B.

- ↑ Anand, Sandhya. Quorum Sensing- Communication Plan For Microbes. Article dated 2010-12-28, retrieved on 2012-04-03.

Further reading

| Library resources about communication |

- Innis, Harold; Innis, Mary Q. (1975). Empire and Communications. Foreword by Marshall McLuhan (Revised ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6119-5. OCLC 19403451.

External links