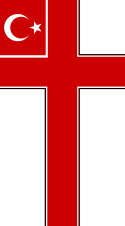

Religion:Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate

| Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate Bağımsız Türk Ortodoks Patrikhanesi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Eastern Orthodox |

| Classification | Independent Eastern Orthodox |

| Primate | Papa Eftim IV |

| Region | Turkey |

| Language | Turkish |

| Liturgy | Byzantine Rite |

| Headquarters | Meryem Ana Church, Istanbul |

| Territory | Turkey, United States |

| Founder | Papa Eftim I |

| Origin | 1922 in Kayseri |

| Independence | 1924 |

| Recognition | Unrecognized by other Eastern Orthodox churches |

| Separated from | Greek Orthodox Church (1922) |

| Members | 47,000[1][2] |

The Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate (Turkish: Bağımsız Türk Ortodoks Patrikhanesi), also referred to as the Turkish Orthodox Church (Turkish: Türk Ortodoks Kilisesi), is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox jurisdiction based in Turkey, descending from Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christian Karamanlides. It was founded in Kayseri by Pavlos Karahisarithis, which became the Patriarch and took the name of Papa Eftim I, in 1922.[3] The Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate is an unrecognized Orthodox Christian denomination and comprises an estimated population of 47,000 Turkish Orthodox Christians.[1][2]

General Congregation of the Anatolian Turkish Orthodox

The start of the Patriarchate can be traced to the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). In 1922 a pro-Turkish Eastern Orthodox group, the General Congregation of the Anatolian Turkish Orthodox (Turkish: Umum Anadolu Türk Ortodoksları Cemaatleri), was set up with the support from the Orthodox bishop of Havza, as well as a number of other congregations[4] representing a genuine movement among the Turkish-speaking, Orthodox Christian population of Anatolia[3] who wished to remain both Orthodox and Turkish.[5] There were calls to establish a new Patriarchate with Turkish as the preferred language of Christian worship.[6]

Foundation

On 15 September 1922 the Autocephalous Orthodox Patriarchate of Anatolia was founded in Kayseri by Pavlos Karahisarithis, a supporter of the General Congregation of the Anatolian Turkish Orthodox.[3] Pavlos Karahisarithis became the Patriarch of this new Orthodox church, and took the name of Papa Eftim I. He was supported by 72 other Turkish Orthodox clerics.[7]

The same year, his supporters, with his tacit support, assaulted Patriarch Meletius IV of Constantinople on 1 June 1923.[8] On 2 October 1923 Papa Eftim besieged the Holy Synod and appointed his own Synod. When Eftim invaded the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate he proclaimed himself "the general representative of all the Orthodox communities" (Bütün Ortodoks Cemaatleri Vekil-i Umumisi).

With a new Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory VII elected on 6 December 1923 after the abdication of Meletius IV, there was another occupation by Papa Eftim I and his followers, when he besieged the Patriarchate for the second time. This time around, they were evicted by the Turkish police.[9]

In 1924, Karahisarithis started to conduct the Christian liturgy in Turkish, and quickly won support from the new Turkish Republic formed after the defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922).[10] He claimed that the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople was ethnically centered and favored the Greek population. Being excommunicated by the Greek Orthodox Church for claiming to be a bishop while still having a wife and due to the fact that married bishops are not allowed in Orthodoxy, Karahisarithis, who later changed his name into Zeki Erenerol, called a Turkish ecclesial congress, which elected him Patriarch in 1924.

On 6 June 1924, in a conference in the Church of the Virgin Mary (Meryem Ana) in Galata, it was decided to transfer the headquarters of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate from Kayseri to Istanbul. In the same session it was also decided that the Church of Virgin Mary would become the Center of the new Patriarchate of the Turkish Orthodox Church.[3]

Karahisarithis and his family members were exempted from the population exchange as per a decision of the Turkish government,[11] although there was not the exemption for either Karahisarithis' followers or the wider communities of Turkish-speaking Christian that was hoped for.[12] Most of the Turkish-speaking Orthodox population remained affiliated with the Greek Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Attempts of integrating the Gagauz to the church

There have been a number of attempts from the 1930s into the 21st century to tie the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate with the ethnically Turkic, Greek Orthodox Gagauz minority in Bessarabia.[13]

In the 1930s, attempts were made to integrate the adherents to the church by Gagauz Christians within Turkey as a congregation for the church. Hamdullah Suphi Tanriöver, Turkish ambassador to Romania tried to attract a number of communities in Gagauzia and Bessarabia regions, at the time integrated with Romania, presently part of the republic of Moldova. Gagauz, Christian Orthodox people spoke a Turkish dialect known as Gagauzo, written using the Greek alphabet. In spite of the similarities with the Greek Orthodox, Turkish-speaking people native to the Cappadocia regions of Anatolia in Turkey. Tanriöver's plans were to establish Gagauz communities in the Turkish region of Marmara, such that these communities would be attached to Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate founded by Eftim I. With the onslaught of the Second World War, plans were put on hold and no further Gagauz were offered to join the church.

The plans of incorporating the Gagauz within the Turkish Orthodox Church resurfaced after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The Turkish government proposed to Stepan Topal, President of the independent region of Gagauzia, to tie the Gagauz Christians, numbering according to estimates to up to 120,000 Christians to the Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate. Stephan Topal visited Turkey in 1994 and met with Papa Eftim III and eventually 100 families accompanied by 4 priests came to Istanbul to be possibly part of the Turkish Orthodox Church community. Nevertheless, the Gagauz leaders reconsidered their plans preferring to stay committed through bonds to the Russian Orthodox Patriarchate instead. Author Mustafa Ekincikli says if the plan had succeeded, the Gagauz would truly establish a valid Turkish Orthodox Church community.

During the 8th Friendship, Brotherhood and Cooperation Congress of Turkish States and Communities held 24–26 March 2000, calls were made particularly to the Gagauz, but also to Moldavian Orthodox Christian communities of Turkish origin in general to consider joining the Turkish Orthodox Church, but this plan was never realized. The efforts of Eftim III however were recognized by the Turkish far-right and ultra-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) as a valid attempt to reunite Turkic peoples with their origin.

A similar project was put into motion in October 2018, when the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited the Republic of Moldova and toured the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia.[14]

Alleged links to the Ergenekon affair

On 22 January 2008, Sevgi Erenerol, granddaughter of the Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate's founder Papa Eftim I, daughter of Papa Eftim III, and sister of the current primate Papa Eftim IV, was arrested for alleged links with a Turkish nationalist underground organization named Ergenekon. At the time of her arrest, she was the spokeswoman for the Patriarchate. It was also alleged that the Patriarchate served as headquarters for the Ergenekon network. Sevgi Erenerol was well known for her militancy in Turkish nationalist activities, as well as for her antagonism to the Ecumenical Greek Patriarchate and the Armenian Apostolic Church. During the time of Alparslan Türkeş, she had run as a parliamentary candidate for the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), political arm of the Turkish far-right and ultra-nationalist Grey Wolves paramilitary organization.[15] On August 5, 2013, Sevgi Erenerol was found guilty of involvement in the so-called "Ergenekon conspiracy" and sentenced to life imprisonment.[16][17] After the retrial she was found not guilty and released on 12 March 2014.[18]

List of Patriarchs of the Turkish Orthodox Church

- Deputy Patriarch

- Prokobiyos (1922-1923) - also known as Prokopios Lazaridis and Prokopios of Iconium, was the metropolitan bishop of Konya. He was elected as the deputy patriarch of General Congregation of the Anatolian Turkish Orthodox in 1922.[19] He died in prison on 31 March 1923.[19]

- Patriarchs

- Papa Eftim I (1923–1962) - Born name Pavlos Karahisarithis, later changed to Zeki Erenerol. As the founder of the Turkish Orthodox Church, he was awarded the "Medal of Independence", the highest decoration of the Republic of Turkey.[20] Following the death of Prokobiyos, he served as the spiritual leader of the Turkish Orthodox Church until 1926. He was elected as the patriarch in 1926 just after his consecration. He resigned due to health reasons in 1962 and died on 14 March 1968.

- Papa Eftim II (1962–1991) - Born name Yorgo, later changed to Turgut Erenerol, elder son of Papa Eftim I. Died on 9 May 1991.

- Papa Eftim III (1991–2002) - Selçuk Erenerol, younger son of Papa Eftim I. Resigned after political disagreements with the Turkish government over growing links between the Turkish authorities[citation needed] and the Greek Ecumenical Patriarch and the Turkish process of accession to the European Union.[citation needed] He died on 20 December 2002 just weeks after his resignation.

- Papa Eftim IV (2002- ) - Paşa Ümit Erenerol, grandson of Papa Eftim I and son of Papa Eftim III. Current primate of the church.

Churches

Today, three churches are owned by Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate and all of them are located in Istanbul. Besides Papa Eftim IV, one priest and three deacons serve the community.

- Meryem Ana Church in Karaköy, is the headquarters of the Patriarchate. The church is located at Ali Paşa Değirmen St. 2, Karaköy. It was built in 1583 by Tryfon Karabeinikov, and was known as the Panaiya Church (in Greek Pan-Hagia Kaphatiani)[14] because it was founded by the Crimean Orthodox community of Kaffa. The church underwent a number of fires and several reconstructions with the major one in 1840, the date to which the present construction belongs. The church community left the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople on March 5, 1924, and adhered to newly found Turkish Orthodox Church.[21] The church's name was changed to Meryem Ana Church (Mother Mary Church) by the Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate in 2006 in honor of Virgin Mary.[14]

- Aziz Nikola Church (in Greek Hagios Nicholaus)[14] is named after Saint Nicholas and was built by Tryfon Karabeinikov and last reconstruction was done in 1804. The church was seized in 1965 from Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and given to the Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate.[22] A fire in 2003 destroyed some parts of the church, rendering it redundant. The church is located at Necatibey St., Karaköy. The church remains abandoned without use.

- Aziz Yahya Church (in Greek Hagios Ioannis Prodromos)[14] is named after John the Baptist. It was built by Tryfon Karabeinikov and is located on Vekilharç St. 15, Karaköy. A fire destroyed it in 1696 and replaced by a new one in 1698. Reconstructions were made in 1836 and finally 1853 by architects Matzini and Stamatis Falieros, with the permission of Sultan Abdülmecit I, giving the church the present form. The church was seized in 1965 alongside Aziz Nikola Church from Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and given to the Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate.[22] Starting the 1990s, the church was leased to the Assyrian Church of the East who lacked a church in Istanbul.

In 1924, Eftim I acquired the Hristos Church illegally from the owner, the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Hristos Church was returned to the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1947, after a legal case, only to be confiscated and bulldozed later on for road enlargement. Compensation for the bulldozed church was paid however to the Erenerol family foundation instead of the Eastern Orthodox community.[14]

Besides these churches, the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate owns an important number of the commercial premises, an office building and a summer palace. They are run under the name of "Independent Turkish Orthodox Foundation".

Turkish Orthodox Church in the United States

The Turkish Orthodox Church in the United States was an Old Catholic group of 20 predominantly African American churches in the United States loosely linked to the Patriarchate. It formed in 1966 under Christopher M. Cragg, an African American physician. He was consecrated by Papa Eftim II in 1966 with the name of Civet Kristof. It continued to exist throughout the 1970s, but fell away in the early 1980s when Cragg opened a clinic in Chicago.[23]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Türkiye'de ortaya çıkan Rum Ortodoks Kilisesi kim veya nedir?". https://zocd.de/t%C3%BCrkiyede-ortaya-%C3%A7%C4%B1kan-rum-ortodoks-kilisesi-kim-veya-nedir.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Türkiye'nin din haritası çizildi". https://www.milliyet.com.tr/dunya/turkiyenin-din-haritasi-cizildi-1155644.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "The Political Role of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate (so-called)". http://www.atour.com/~aahgn/news/20040123b.html.

- ↑ Page 152, The last dragoman: the Swedish orientalist Johannes Kolmodin as scholar, Elisabeth Özdalga

- ↑ Abstract of Baba Eftim et l'Église orthodoxe turque, Journal of Eastern Christian Studies

- ↑ Page 153, The last dragoman: the Swedish orientalist Johannes Kolmodin as scholar, Elisabeth Özdalga

- ↑ Alexis Alexandridis, "The Greek Minority in Istanbul and Greek-Turkish Relations, 1918-1974." Athens 1992, p. 151. cited by the Spanish Wikipedia

- ↑ "Ecumenical Patriarchate Under the Turkish Republic". http://www.orthodoxchristianity.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&catid=14:articles&id=40:ecumenical-patriarchate-under-the-turkish-republic.

- ↑ "The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate and the Turkish-Greek Relations, 1923-1940". http://www.turkishweekly.net/article/86/the-greek-orthodox-patriarchate-and-the-turkish-greek-relations-1923-1940.html.

- ↑ Leader of Turkish Nationalist Church Dies

- ↑ Ayda Kayar and Mustafa Kinali, "Cemaati değil malı olan patrikhane," Hürriyet, January 30, 2008 (in Turkish)

- ↑ "Home Page – The TLS". https://www.the-tls.co.uk/.

- ↑ The Political Role of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate (so-called) by Dr. Racho Donef

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Abdullah Bozkurt (5 February 2019). "Turkish intel agency-linked bogus Orthodox church campaigns against ecumenical patriarch". NordicMonitor.com. https://www.nordicmonitor.com/2019/02/turkish-intelligence-linked-bogus-orthodox-church-campaigns-against-ecumenical-patriarch/.

- ↑ "Ergenekon’un karargahı Türk Ortodoks Kilisesi," Milliyet, January 28, 2008 (in Turkish)

- ↑ Gul Tuysuz Talia Kayali and Joe Sterling. "Ex-military chief gets life in Turkish trial". https://edition.cnn.com/2013/08/05/world/europe/turkey-ergenekon-verdict/index.html.

- ↑ "Bianet: Verdict Issued in Ergenekon Case". http://www.bianet.org/english/other/148988-verdict-issued-in-ergenekon-case.

- ↑ "Sevgi Erenerol tahliye edildi" (in tr). https://www.cnnturk.com/haber/turkiye/sevgi-erenerol-tahliye-edildi.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Turkish Orthodox Christians & The Establishment of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate, Türk-İslam Medeniyeti Akademik Araştırmalar Dergisi, 2009. vol.8, p.7

- ↑ "Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy". http://www.eliamep.gr/old/eliamep/content/home/media/opinions/latest_opinions/the_ergenekon_affair/en/index.html.

- ↑ Türkiye'de Din İmtiyazları, Ankara University Journal of Faculty of Law. 1953, C.X. p.1

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Milliyet. September 25, 1965

- ↑ Melton, J. Gordon (ed.). The Encyclopedia of American Religions: Vol. 1. Tarrytown, NY: Triumph Books (1991); pg. 135

Bibliography

- Foti Benlisoy, “Papa Eftim and the Foundation of the Turkish Orthodox Church”, Unpublished master thesis, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, 2002.

- Dr. Bestami Sadi Bilgic, « The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate and the Turkish-Greek Relations, 1923-1940 », Turkish Week, June 15, 2005 (about the Phanar occupation episode).

- Xavier Luffin, « Le Patriarcat orthodoxe turc », Het Christelijk Oosten, 52, Nimègue, 2000, p. 73-96.

- Xavier Luffin, « Baba Eftim et l'Église orthodoxe turque - De l'usage politique d'une institution religieuse », Journal of Eastern Christian Studies, Volume 52, issue 1-2, 2000. abstract in Journal of Eastern Christian Studies.

- Harry J. Psomiades, « The Ecumenical Patriarchate Under the Turkish Republic: The First Ten Years », Balkan Studies 2, Thessaloniki, 1961, pp. 47-70.

- J. Xavier, «An Autocephalus Turkish Orthodox Church», Eastern Church Review, 3 (1970/1971).