Physics:Penning–Malmberg trap

The Penning–Malmberg trap (PM trap), named after Frans Penning and John Malmberg, is an electromagnetic device used to confine large numbers of charged particles of a single sign of charge. Much interest in Penning–Malmberg (PM) traps arises from the fact that if the density of particles is large and the temperature is low, the gas will become a single-component plasma.[1] While confinement of electrically neutral plasmas is generally difficult, single-species plasmas (an example of a non-neutral plasma) can be confined for long times in PM traps. They are the method of choice to study a variety of plasma phenomena. They are also widely used to confine antiparticles such as positrons (i.e., anti-electrons) and antiprotons for use in studies of the properties of antimatter and interactions of antiparticles with matter.[2]

Design and operation

A schematic design of a PM trap is shown in Fig. 1.[1][2] Charged particles of a single sign of charge are confined in a vacuum inside an electrode structure consisting of a stack of hollow, metal cylinders. A uniform axial magnetic field [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is applied to inhibit positron motion radially, and voltages are imposed on the end electrodes to prevent particle loss in the magnetic field direction. This is similar to the arrangement in a Penning trap, but with an extended confinement electrode to trap large numbers of particles (e.g., [math]\displaystyle{ N\geq10^{10} }[/math]).

Such traps are renowned for their good confinement properties. This is due to the fact that, for a sufficiently strong magnetic field, the canonical angular momentum [math]\displaystyle{ L_z }[/math] of the charge cloud (i.e., including angular momentum due to the magnetic field B) in the direction [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] of the field is approximately[3]

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \quad L_z \approx-(\frac{m\omega_c}{2}){\sum}_{j=1}^N r_j^2,\qquad }[/math]

()

where [math]\displaystyle{ r_j }[/math] is the radial position of the [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]th particle, [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is the total number of particles, and [math]\displaystyle{ {\omega_c}=eB/m }[/math] is the cyclotron frequency, with particle mass m and charge e. If the system has no magnetic or electrostatic asymmetries in the plane perpendicular to [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math], there are no torques on the plasma; thus [math]\displaystyle{ L_z }[/math] is constant, and the plasma cannot expand. As discussed below, these plasmas do expand due to magnetic and/or electrostatic asymmetries thought to be due to imperfections in trap construction.

The PM traps are typically filled using sources of low energy charged particles. In the case of electrons, this can be done using a hot filament or electron gun.[4] For positrons, a sealed radioisotope source and "moderator" (the latter used to slow the positrons to electron-volt energies) can be used.[2] Techniques have been developed to measure the plasma length, radius, temperature, and density in the trap, and to excite plasma waves and oscillations.[2] It is frequently useful to compress plasmas radially to increase the plasma density and/or to combat asymmetry-induced transport.[5] This can be accomplished by applying a torque on the plasma using rotating electric fields [the so-called "rotating wall" (RW) technique],[6][7][8] or in the case of ion plasmas, using laser light.[9] Very long confinement times (hours or days) can be achieved using these techniques.

Particle cooling is frequently necessary to maintain good confinement (e.g., to mitigate the heating from RW torques). This can be accomplished in a number of ways, such as using inelastic collisions with molecular gases,[2] or in the case of ions, using lasers.[9][10] In the case of electrons or positrons, if the magnetic field is sufficiently strong, the particles will cool by cyclotron radiation.[11]

History and uses

The confinement and properties of single species plasmas in (what are now known as) PM traps was first studied by John Malmberg and John DeGrassie.[4] Confinement was shown to be excellent as compared to that for neutral plasmas. It was also shown that, while good, confinement is not perfect and there are particle losses.

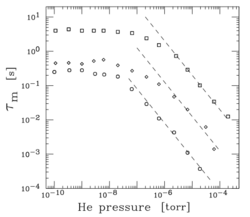

Penning–Malmberg traps have been used to study a variety of transport mechanisms. Figure 2 shows an early study of confinement in a PM trap as a function of a background pressure of helium gas. At higher pressures, transport is due to electron-atom collisions, while at lower pressures, there is a pressure-independent particle loss mechanism. The latter (“anomalous transport”) mechanism has been shown to be due to inadvertent magnetic and electrostatic asymmetries and the effects of trapped particles.[5] There is evidence that confinement in PM traps is improved if the main confinement electrode (blue in Fig. 1) is replaced by a series of coaxial cylinders biased to create a smoothly varying potential well (a “multi-ring PM trap”).[12]

One fruitful area of research arises from the fact that plasmas in PM traps can be used to model the dynamics of inviscid two-dimensional fluid flows.[14][15][16][17] PM traps are also the device of choice to accumulate and store anti-particles such as positrons and antiprotons.[2] One has been able to create positron and antiproton plasmas[18] and to study electron-beam positron plasma dynamics.[19]

Pure ion plasmas can be laser-cooled into crystalline states.[20] Cryogenic pure-ion plasmas are used to study quantum entanglement.[21] The PM traps also provide an excellent source for cold positron beams. They have been used to study with precision positronium (Ps) atoms (the bound state of a positron and an electron, lifetime ≤ 0.1 μs) and to create and study the positronium molecule (Ps[math]\displaystyle{ _2 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ e^+e^-e^+e^- }[/math]).[22][23] Recently PM-trap-based positron beams have been used to produce practical Ps-atom beams.[24][25][26]

Antihydrogen is the bound state of an antiproton and a positron and the simplest antiatom. Nested PM traps (one for antiprotons and another for positrons) have been central to the successful efforts to create, trap and to compare the properties of antihydrogen with those of hydrogen.[27][28][29] The antiparticle plasmas (and electron plasmas used to cool the antiprotons) are carefully tuned with an array of recently developed techniques to optimize the production antihydrogen atoms.[30] These neutral antiatoms are then confined in a minimum-magnetic-field trap.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dubin, Daniel H. E.; O’Neil, T. M. (1999). "Trapped nonneutral plasmas, liquids, and crystals (the thermal equilibrium states)". Reviews of Modern Physics 71 (1): 87–172. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.87. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 1999RvMP...71...87D.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Danielson, J. R.; Dubin, D. H. E.; Greaves, R. G.; Surko, C. M. (2015). "Plasma and trap-based techniques for science with positrons". Reviews of Modern Physics 87 (1): 247–306. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.87.247. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 2015RvMP...87..247D.

- ↑ O’Neil, T. M. (1980). "A confinement theorem for nonneutral plasmas". Physics of Fluids 23 (11): 2216. doi:10.1063/1.862904. ISSN 0031-9171. Bibcode: 1980PhFl...23.2216O.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Malmberg, J. H.; deGrassie, J. S. (1975). "Properties of Nonneutral Plasma". Physical Review Letters 35 (9): 577–580. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.577. ISSN 0031-9007. Bibcode: 1975PhRvL..35..577M.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kabantsev, A. A.; Driscoll, C. F. (2002). "Trapped-Particle Modes and Asymmetry-Induced Transport in Single-Species Plasmas". Physical Review Letters 89 (24): 245001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.245001. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 12484950. Bibcode: 2002PhRvL..89x5001K.

- ↑ Anderegg, F.; Hollmann, E. M.; Driscoll, C. F. (1998). "Rotating Field Confinement of Pure Electron Plasmas Using Trivelpiece-Gould Modes". Physical Review Letters 81 (22): 4875–4878. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.4875. ISSN 0031-9007. Bibcode: 1998PhRvL..81.4875A.

- ↑ Huang, X.-P.; Anderegg, F.; Hollmann, E. M.; Driscoll, C. F.; O'Neil, T. M. (1997). "Steady-State Confinement of Non-neutral Plasmas by Rotating Electric Fields". Physical Review Letters 78 (5): 875–878. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.875. ISSN 0031-9007. Bibcode: 1997PhRvL..78..875H.

- ↑ Danielson, J. R.; Surko, C. M. (2006). "Radial compression and torque-balanced steady states of single-component plasmas in Penning–Malmberg traps". Physics of Plasmas 13 (5): 055706. doi:10.1063/1.2179410. ISSN 1070-664X. Bibcode: 2006PhPl...13e5706D.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jelenković, B. M.; Newbury, A. S.; Bollinger, J. J.; Itano, W. M.; Mitchell, T. B. (2003). "Sympathetically cooled and compressed positron plasma". Physical Review A 67 (6): 063406. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.67.063406. ISSN 1050-2947. Bibcode: 2003PhRvA..67f3406J.

- ↑ Bollinger, J. J.; Wineland, D. J.; Dubin, Daniel H. E. (1994). "Non‐neutral ion plasmas and crystals, laser cooling, and atomic clocks*". Physics of Plasmas 1 (5): 1403–1414. doi:10.1063/1.870690. ISSN 1070-664X. Bibcode: 1994PhPl....1.1403B.

- ↑ O’Neil, T. M. (1980). "Cooling of a pure electron plasma by cyclotron radiation". Physics of Fluids 23 (4): 725. doi:10.1063/1.863044. ISSN 0031-9171. Bibcode: 1980PhFl...23..725O.

- ↑ Mohamed, Tarek (2009). "Experimental studies of the confinement of electron plasma in a multi-ring trap". Plasma Devices and Operations 17 (4): 250–256. doi:10.1080/10519990903043748. ISSN 1051-9998.

- ↑ Malmberg, J. H.; Driscoll, C. F. (1980). "Long-Time Containment of a Pure Electron Plasma". Physical Review Letters 44 (10): 654–657. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.44.654. ISSN 0031-9007. Bibcode: 1980PhRvL..44..654M.

- ↑ Fine, K. S.; Cass, A. C.; Flynn, W. G.; Driscoll, C. F. (1995). "Relaxation of 2D Turbulence to Vortex Crystals". Physical Review Letters 75 (18): 3277–3280. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.3277. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10059543. Bibcode: 1995PhRvL..75.3277F.

- ↑ Schecter, D. A.; Dubin, D. H. E.; Fine, K. S.; Driscoll, C. F. (1999). "Vortex crystals from 2D Euler flow: Experiment and simulation". Physics of Fluids 11 (4): 905–914. doi:10.1063/1.869961. ISSN 1070-6631. Bibcode: 1999PhFl...11..905S.

- ↑ Schecter, David A.; Dubin, Daniel H. E. (2001). "Theory and simulations of two-dimensional vortex motion driven by a background vorticity gradient". Physics of Fluids 13 (6): 1704–1723. doi:10.1063/1.1359763. ISSN 1070-6631. Bibcode: 2001PhFl...13.1704S.

- ↑ Hurst, N. C.; Danielson, J. R.; Dubin, D. H. E.; Surko, C. M. (2018). "Experimental study of the stability and dynamics of a two-dimensional ideal vortex under external strain". Journal of Fluid Mechanics 848: 256–287. doi:10.1017/jfm.2018.311. ISSN 0022-1120. Bibcode: 2018JFM...848..256H.

- ↑ Ahmadi, M.; Alves, B. X. R.; Baker, C. J.; Bertsche, W.; Butler, E.; Capra, A.; Carruth, C.; Cesar, C. L. et al. (2017). "Antihydrogen accumulation for fundamental symmetry tests". Nature Communications 8 (1): 681. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00760-9. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 28947794. Bibcode: 2017NatCo...8..681A.

- ↑ Greaves, R. G.; Surko, C. M. (1995). "An Electron-Positron Beam-Plasma Experiment". Physical Review Letters 75 (21): 3846–3849. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.3846. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10059746. Bibcode: 1995PhRvL..75.3846G.

- ↑ Mitchell, T. B.; Bollinger, J. J.; Dubin DHE; Huang, X.; Itano, W. M.; Baughman, R. H. (1998). "Direct Observations of Structural Phase Transitions in Planar Crystallized Ion Plasmas". Science 282 (5392): 1290–1293. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1290. PMID 9812887. Bibcode: 1998Sci...282.1290M.

- ↑ Bohnet, J. G.; Sawyer, B. C.; Britton, J. W.; Wall, M. L.; Rey, A. M.; Foss-Feig, M.; Bollinger, J. J. (2016). "Quantum spin dynamics and entanglement generation with hundreds of trapped ions". Science 352 (6291): 1297–1301. doi:10.1126/science.aad9958. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27284189. Bibcode: 2016Sci...352.1297B.

- ↑ Cassidy, D. B.; Mills, A. P. (2007). "The production of molecular positronium". Nature 449 (7159): 195–197. doi:10.1038/nature06094. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17851519. Bibcode: 2007Natur.449..195C.

- ↑ Cassidy, D. B.; Hisakado, T. H.; Tom, H. W. K.; Mills, A. P. (2012). "Optical Spectroscopy of Molecular Positronium". Physical Review Letters 108 (13): 133402. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.133402. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 22540698. Bibcode: 2012PhRvL.108m3402C.

- ↑ Jones, A. C. L.; Moxom, J.; Rutbeck-Goldman, H. J.; Osorno, K. A.; Cecchini, G. G.; Fuentes-Garcia, M.; Greaves, R. G.; Adams, D. J. et al. (2017). "Focusing of a Rydberg Positronium Beam with an Ellipsoidal Electrostatic Mirror". Physical Review Letters 119 (5): 053201. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.053201. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 28949762. Bibcode: 2017PhRvL.119e3201J.

- ↑ Michishio, K.; Chiari, L.; Tanaka, F.; Oshima, N.; Nagashima, Y. (2019). "A high-quality and energy-tunable positronium beam system employing a trap-based positron beam". Review of Scientific Instruments 90 (2): 023305. doi:10.1063/1.5060619. ISSN 0034-6748. PMID 30831693. Bibcode: 2019RScI...90b3305M.

- ↑ Cassidy, David B. (2018). "Experimental progress in positronium laser physics". The European Physical Journal D 72 (3): 53. doi:10.1140/epjd/e2018-80721-y. ISSN 1434-6060. Bibcode: 2018EPJD...72...53C.

- ↑ Amoretti, M.; Amsler, C.; Bonomi, G.; Bouchta, A.; Bowe, P.; Carraro, C.; Cesar, C. L.; Charlton, M. et al. (2002). "Production and detection of cold antihydrogen atoms". Nature 419 (6906): 456–459. doi:10.1038/nature01096. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12368849. Bibcode: 2002Natur.419..456A. http://cds.cern.ch/record/581488.

- ↑ Gabrielse, G.; Bowden, N. S.; Oxley, P.; Speck, A.; Storry, C. H.; Tan, J. N.; Wessels, M.; Grzonka, D. et al. (2002). "Driven Production of Cold Antihydrogen and the First Measured Distribution of Antihydrogen States". Physical Review Letters 89 (23): 233401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.233401. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 12485006. Bibcode: 2002PhRvL..89w3401G. http://juser.fz-juelich.de/record/25767.

- ↑ The ALPHA Collaboration, (2011). "Confinement of antihydrogen for 1,000 seconds" (in en). Nature Physics 7 (7): 558–564. doi:10.1038/nphys2025. ISSN 1745-2473. http://www.nature.com/articles/nphys2025.

- ↑ Ahmadi, M.; Alves, B. X. R.; Baker, C. J.; Bertsche, W.; Capra, A.; Carruth, C.; Cesar, C. L.; Charlton, M. et al. (2018). "Enhanced Control and Reproducibility of Non-Neutral Plasmas". Physical Review Letters 120 (2): 025001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.025001. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 29376718. Bibcode: 2018PhRvL.120b5001A.

- ↑ Andresen, G. B.; Ashkezari, M. D.; Baquero-Ruiz, M.; Bertsche, W.; Bowe, P. D.; Butler, E.; Cesar, C. L.; Chapman, S. et al. (2010). "Trapped antihydrogen". Nature 468 (7324): 673–676. doi:10.1038/nature09610. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21085118. Bibcode: 2010Natur.468..673A.