Physics:Zograscope

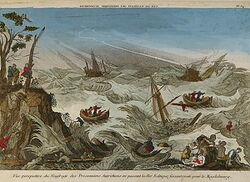

A zograscope is an optical device for magnifying flat pictures that also has the property of enhancing the sense of the depth shown in the picture. It consists of a large magnifying lens through which the picture is viewed. Devices containing only the lens are sometimes referred to as graphoscopes. Other models have the lens mounted on a stand in front of an angled mirror. This allows someone to sit at a table and to look through the lens at the picture flat on the table. Pictures viewed in this way need to be left-right reversed; this is obvious in the case of writing. A print made for this purpose, typically with extensive graphical projection perspective, is called a vue d'optique or "perspective view",

Zograscopes were popular during the later half of the 18th century as parlour entertainments.[1] Most existing ones from that time are fine furniture, with turned stands, mouldings, brass fittings, and fine finishes.

According to Michael Quinion, the origin of the term is lost, but it is also known as a diagonal mirror, as an optical pillar machine, or as an optical diagonal machine.[2]

In Japan, the zograscope became known as 和蘭眼鏡 (Oranda megane, 'Dutch glasses') or 覗き眼鏡 (nozoki megane 'peeping glasses'), and the pictures were known as 眼鏡絵 (megane-e, 'optique picture') 繰絵 (karakuri-e 'tricky picture').

History

- In 1570, John Dee wrote A very fruitfull Preface ... specifying the chiefe Mathematicall Scieces, etc. in which he defined "zographie" as a mathematical art for representing visual images.[3][4]

- In 1677, German writer Johann Christoph Kohlhans described the effect of a convex lens in a camera obscura as if the subject appeared "naked before the eye in width, breadth, familiarity and distance".[5]

- In 1692, William Molyneux wrote in his Dioptrica Nova how "Pieces of Perspective appear Natural and strong through Convex Glasses duly apply'd".[5]

- Raree show boxes became very popular in the 17th century in The Netherlands.[6] Some artists from the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age painting, like Pieter Janssens Elinga and Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten created a type of peep shows with an illusion of depth perception by manipulating the perspective of the view seen inside, usually the interior of a room. From around 1700 many of such "perspective boxes" or "optica" had a bi-convex lens with a large diameter and small dioptre for an exaggerated perspective, giving a stronger illusion of depth. Most pictures showed architectural and topographical subjects with linear perspectives.[7][8]

- In 1730, the first zograscopes, then called "optiques", were developed in Paris.[3] Many perspective views, mainly of scenes from France and Germany but some from England, were published.[9] Optiques incorporated a mirror but lacked any simple means of varying the distance of the lens from the image.[3]

- In 1745, the first English versions of the devices began to appear and soon many perspective views were printed for it, mostly of views with urban architecture.[5] The oldest known reference to the English device is found in an advertisement in an English newspaper from April 1746.[10] The term optical diagonal machine dates from as early as 1750.[3]

Experience of zograscope viewing

Zograscopes created an unprecedentedly realistic experience of depicted scenes, so much so that Blake (2003) described it as "virtual reality".[5] A zograscope allowed viewers to move their eyes over very large scenes, yielding an immersive experience.

Koenderink et al. (2013) showed that viewing photographs with a zograscope allowed observers to see depicted objects, such as Rodin's Danaid (Rodin), in objectively measured depth.[11]

Explanation

Magnification of images was well understood by the time the first devices were constructed in the early 18th century. Basically, the image is placed at the focal point of a biconvex or plano-convex lens (a magnifying glass) allowing someone to view the magnified image at varying distances on the other side of the lens.[11] Court and von Rorh (1935) suggested that the popularity of the early French models was because they allowed presbyopic purchasers to see the images clearly despite the French fashion against wearing glasses.[9] But Chaldecott (1953) doubted this could have been the sole reason for the devices' enduring popularity, leaving the major factor to be the realistic appearance of the depicted images.[3]

A zograscope makes a realistic experience for someone looking through it is by enhancing depth perception. One way is by minimizing other depth cues that specify the flatness and pictorial nature of the picture. The image is magnified, perhaps giving it a visual angle similar to the real scene the picture is depicting. The edges of the picture are blocked by the frame of the lens. The light coming from the lens to the eye is collimated, preventing accommodation. In early prints of interior scenes, some objects were hand-tinted with saturated colors whereas the background was tinted with "a pale wash"[5] exploiting color contrast as a depth cue.[12]

A second way a zograscope could enhance depth perception is by creating binocular stereopsis. Because each eye views the image from a different position, the surface of the picture could have binocular disparity from different magnification for the two eyes or from differences in the rotation of the images received by the eyes, so-called cyclodisparity.[11] Such disparities create an overall slant of the picture surface around the vertical meridian[13] or horizontal meridian[14] respectively. As well, coloured parts of the image will be refracted differently for each eye, creating a version of chromostereopsis. Even if the binocular disparity were incorrect for the surface of the image or any coloured parts of it, the stereoscopic information tends to integrate with the other depth information in the image.

Construction of modern variation

A simple zograscope can be built from a frame (by cutting a rectangular opening in the bottom of a cardboard box) and placing in the frame a large, magnifying, fresnel lens available from stationery stores. When this is placed over a computer monitor displaying a photograph of a natural scene, the depicted depth will be enhanced.

See also

- Peep show

- Stereoscope

- Optical toys

References

- ↑ Permutt, Cyril (1976). Collecting Old Cameras. New York: DaCapo Press. pp. 23, 27. ISBN 978-0-306-70855-8.

- ↑ Worldwidewords.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Chaldecott, J.A. (1953). "The zograscope or optical diagonal machine". Annals of Science 9 (4): 315–322. doi:10.1080/00033795300200243.

- ↑ Dee, J. (1570). [A very fruitfull Præface made by M. I. Dee, specifying the chiefe Mathematicall Sciẽces ...] In H. Billingsley, The elements of geometrie of the most auncient pholosopher Euclide of Megrara. London: John Daye. Retrieved from www.gutenberg.org

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Blake, E. C. (2003). Zograscopes, virtual reality, and the mapping of polite society in eighteenth-century England. In L. Gitelman, & G. B. Pingree (Eds.), New Media, 1740-1915 (pp. 1-30). Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress-request.mit.edu/sites/default/files/titles/content/9780262572286_sch_0001.pdf

- ↑ "Peep-show box - Oxford Reference". http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100313907.

- ↑ "Peepshow". http://www.visual-media.eu/vue-optique.html.

- ↑ Wagenaar; Duller; Wagenaar-Fischer. Dutch Perspectives.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Court, T. H., & von Rorh, M. (1935). On old instruments both for the accurate drawing and the correct viewing of perspectives. The Photographic Journal, 75(February), 54-66. Retrieved from https://archive.rps.org/archive/volume-75/734093?q=rohr%201935>

- ↑ Clayton, Tim (1997). The English Print 1688-1802. pp. 140–141.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Koenderink, Jan; Wijntjes, Maarten; Van Doorn, Andrea (2013). "Zograscopic Viewing". i-Perception 4 (3): 192–206. doi:10.1068/i0585. PMID 23799196.

- ↑ Troscianko, Tom; Montagnon, Rachel; Clerc, Jacques Le; Malbert, Emmanuelle; Chanteau, Pierre-Louis (1991). "The role of colour as a monocular depth cue". Vision Research 31 (11): 1923–1929. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(91)90187-A. PMID 1771776.

- ↑ Ogle, K. N. (1950). Researchers in binocular vision. New York: Hafner Publishing Company.

- ↑ Blakemore, Colin; Fiorentini, Adriana; Maffei, Lamberto (1972). "A second neural mechanism of binocular depth discrimination". The Journal of Physiology 226 (3): 725–749. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp010006. PMID 4564896.

External links