Earth:Internet GIS

Internet GIS, or Internet geographic information systems, is a term that refers to a broad set of technologies and applications that employ the Internet to access, analyze, visualize, and distribute spatial data.[1][2][3]

Introduction

Internet GIS is an outgrowth of traditional geographic information systems or GIS, and represents a paradigm shift from conducting GIS on an individual computer to working with remotely distributed data and functions.[1] Internet GIS is a subset of Distributed GIS, but specifically uses the internet rather than generic computer networks. Internet GIS applications are often, but not exclusively, conducted through the World Wide Web, giving rise to the sub-branch of Web GIS, often used interchangeably with Internet GIS.[1][4][5][6][7] While Web GIS is has become nearly synonymous with Internet GIS, the two are as distinct as the internet is from the World Wide Web.[1][4][5][6][7] Likewise, Internet GIS is as distinct from distributed GIS as the Internet is from distributed computer networks in general.[1]

History

The history of Internet geographic information systems is linked to the history of the computer, the internet, and the quantitative revolution in geography. Geography tends to adapt technologies from other disciplines rather than innovating and inventing the technologies employed to conduct geographic studies.[8] The computer and internet are not an exception, and were rapidly investigated to purpose towards the needs of geographers. In 1959, Waldo Tobler published the first paper detailing the use of computers in map creation.[9] This was the beginning of computer cartography, or the use of computers to create maps.[10][11] In 1960, the first true geographic information system capable of storing, analyzing, changing, and creating visualizations with spatial data was created by Roger Tomlinson on behalf of the Canadian Government to manage natural resources.[12][13] These technologies represented a paradigm shift in cartography and geography, with desktop computer cartography facilitated through GIS rapidly replaced traditional ways of making maps.[8] The emergence of GIS and computer technology contributed to the quantitative revolution in geography and the emergence of the branch of technical geography.[14][15]

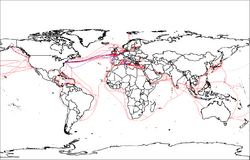

As computer technology advanced and the desktop machine became the default for producing maps. These computers were networked together to share data and processing power and create redundant communications for defense applications.[7] This computer network evolved into the internet, and by the late 1980s, the internet was available in some people's homes.[7] Over time, the internet moved from a novelty to a major part of daily life. Using the internet, it was no longer necessary to store all data for a project locally, and communications were vastly improved. Following this trend, GIScientists began developing methods for combining the internet and GIS. This process accelerated in the 1990s, with the creation of the World Wide Web in 1990 and first major web mapping program capable of distributed map creation appearing in 1993.[1][7][16] This software, named PARC Map Viewer, was unique in that it facilitated dynamic user map generation, rather than static images.[16] This software also allowed for users to employ GIS without having it locally installed on their machine.[4][16] The US federal government made the TIGER Mapping Service available to the public in 1995, which facilitated desktop and Web GIS by hosting US boundary data.[4] In 1996, MapQuest became available to the public, facilitating navigation and trip planning.[4]

In 1997, Esri began to focus on their desktop GIS software, which in 2000 became ArcGIS.[17] This led to Esri dominating the GIS industry for the next several years.[7] In 2000 Esri launched the Geography Network, which offered some web GIS functions. In 2014, ArcGIS Online replaced this, and offers significant WebGIS functions including hosting, manipulating, and visualizing data in dynamic applications.[4][5][7]

Web GIS

The World Wide Web is an information system that uses the internet to host, share, and distribute documents, images, and other data.[18] WebGIS involves using the World Wide Web to facilitate GIS tasks traditionally done on a desktop computer, as well as enabling the sharing of maps and spatial data. Most, but not all, internet GIS is WebGIS.[4][5]

Geospatial web services

Geospatial web services are distinct software packages available on the World Wide Web that can be employed to perform a function with spatial data.[3]

Web feature services

Web feature services allow users to access, edit, and make use of hosted geospatial feature datasets.[3]

Web processing services

Web processing services allow users to perform GIS calculations on spatial data.[3] Web processing services standardize inputs, and outputs, for spatial data within an internet GIS and may have standardized algorithms for spatial statistics.

Web mapping

Web mapping involves using distributed tools to create and host both static and dynamic maps.[1][3][4][5] It is different than desktop digital cartography in that the data, software, or both might not be stored locally and are often distributed across many computers. Web mapping allows for the rapid distribution of spatial visualizations without the need for printing.[8] They also facilitates rapid updating to reflect new datasets and allow for interactive datasets that would be impossible in print media. Web mapping was employed extensively during the COVID-19 pandemic to visualize the datasets in close to real-time.[19][20][21]

Geospatial Semantic Web

Mobile GIS

Cell phones and other wireless communication forms have become common in society.[1][4][5] Many of these devices are connected to the internet and can access internet GIS applications like any other computer.[4][5] Unlike traditional computers, however, these devices generate immense amounts of spatial data available to the device user and many governments and private entities.[4][5] The tools, applications, and hardware used to facilitate GIS through the use of wireless technology is mobile GIS. Used by the holder of the device, mobile GIS enables navigation applications like Google Maps to help the user navigate to a location.[4][5] When used by private firms, the location data collected can help businesses understand foot traffic in an area to optimize business practices.[4][5] Governments can use this data to monitor citizens. Access to locational data by third parties has led to privacy concerns.[4][5]

Mobile GIS is a subset of distributed GIS, and has a significant overlap with internet GIS, however not all mobile GIS employs the internet.[1] Thus, the categories are distinct.[1]

Criticism

By their definition, maps can never be perfect and are simplifications of reality.[22] Ethical cartographers try to keep these inaccuracies documented and to a minimum, while encouraging critical perspectives when using a map. Internet GIS has brought map-making tools to the general public, facilitating the rapidly disseminating these maps.[23] While this is potentially positive, it also means that people without cartographic training can easily make and disseminate misleading maps to a wide audience.[8][21][22] Further, malicious actors can quickly spread intentionally misleading spatial information while hiding the source.[22]

See also

- AM/FM/GIS

- ArcGIS

- At-location mapping

- Automotive navigation system

- Collaborative mapping

- Comparison of GIS software

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Counter-mapping

- CyberGIS

- Digital geologic mapping

- Distributed GIS

- Geographic information systems in geospatial intelligence

- Geomatics

- GIS and aquatic science

- GIS and public health

- GISCorps

- GIS Day

- GIS in archaeology

- Historical GIS

- Integrated Geo Systems

- List of GIS data sources

- List of GIS software

- Map database management

- Participatory GIS

- QGIS

- SAGA GIS

- Technical geography

- TerrSet

- Tobler's first law of geography

- Tobler's second law of geography

- Traditional knowledge GIS

- Virtual globe

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Peng, Zhong-Ren; Tsou, Ming-Hsiang (2003). Internet GIS: Distributed Information Services for the Internet and Wireless Networks. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-35923-8. OCLC 50447645. https://archive.org/details/internetgisdistr0000peng.

- ↑ Moretz, David (2008). "Internet GIS". in Shekhar, Shashi; Xiong, Hui. Encyclopedia of GIS. New York: Springer. pp. 591–596. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-35973-1_648. ISBN 978-0-387-35973-1. OCLC 233971247. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofgi0000unse_i4o0/page/591.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Zhang, Chuanrong; Zhao, Tian; Li, Weidong (2015). Geospatial Semantic Web. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17801-1. ISBN 978-3-319-17800-4. OCLC 911032733.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Fu, Pinde; Sun, Jiulin (2011). Web GIS: Principles and Applications. Redlands, Calif.: ESRI Press. ISBN 978-1-58948-245-6. OCLC 587219650. https://archive.org/details/webgisprinciples0000fupi.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Fu, Pinde (2016). Getting to Know Web GIS (2 ed.). Redlands, Calif.: ESRI Press. ISBN 9781589484634. OCLC 928643136. https://archive.org/details/gettingtoknowweb0000fupi.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hojaty, Majid (21 February 2014). "What is the Difference Between Web GIS and Internet GIS?". https://www.gislounge.com/difference-web-gis-internet-gis/#:~:text=Web%20GIS%20originates%20from%20a,kind%20of%20distributed%20information%20system..

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Peterson, Michael P. (2014). Mapping in the Cloud. New York: The Guiford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-1041-2. OCLC 855580732. https://archive.org/details/mappingincloud0000pete.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Monmonier, Mark S. (1985). Technological Transition in Cartography. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299100707. OCLC 11399821. https://archive.org/details/technologicaltra0000monm.

- ↑ Tobler, Waldo (1959). "Automation and Cartography". Geographical Review 49 (4): 526–534. doi:10.2307/212211. https://www.jstor.org/stable/212211. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ Clark, Keith (1995). Analytic and Computer Cartography. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0133419002.

- ↑ Monmonier, Mark (1982). Computer-Assisted Cartography: Principles and Prospects 1st Edition (1 ed.). Pearson College Div. ISBN 9780131653085.

- ↑ "History of GIS | Early History and the Future of GIS - Esri" (in en-us). https://www.esri.com/en-us/what-is-gis/history-of-gis.

- ↑ "Roger Tomlinson". UCGIS. 21 February 2014. http://ucgis.org/ucgis-fellow/roger-tomlinson.

- ↑ Haidu, Ionel (2016). "What is Technical Geography – a letter from the editor". Geographia Technica 11: 1–5. doi:10.21163/GT_2016.111.01.

- ↑ Ormeling, Ferjan (2009). Technical Geography Core concepts in the mapping sciences. pp. 482. ISBN 978-1-84826-960-6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Putz, Steve (November 1994). "Interactive information services using World-Wide Web hypertext". Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 27 (2): 273–280. doi:10.1016/0169-7552(94)90141-4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0169755294901414. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Maguire, David J (May 2000). "Esri's New ArcGIS Product Family". ArcNews (Esri). http://www.esri.com/news/arcnews/summer00articles/esrisnew.html.

- ↑ "What is the difference between the Web and the Internet?". W3C. 2009. http://www.w3.org/Help/#webinternet.

- ↑ Dong, Ensheng; Du, Hongru (2020). "An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time". The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20 (5): 533–534. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. PMID 32087114.

- ↑ Everts, Jonathan (2020). "The dashboard pandemic". Dialogues in Human Geography 10 (2): 260–264. doi:10.1177/2043820620935355. https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/9YTSZSDCXKMR3IININZ7/full. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Adams, Aaron; Chen, Xiang; Li, Weidong; Zhang, Chuanrong (2020). "The disguised pandemic: the importance of data normalization in COVID-19 web mapping". Public Health 183: 36–37. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.034. PMID 32416476.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Monmonier, Mark (10 April 2018). How to lie with maps (3 ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226435923.

- ↑ Monmonier, Mark (1 June 1990). "Ethics and Map Design: Six Strategies for Confronting the Traditional One-Map Solution". Cartographic Perspectives 1 (10): 3–8. doi:10.14714/CP10.1052. https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp10-monmonier. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

{{Navbox | name = Geography topics | state = collapsed | title = Geography topics | bodyclass = hlist

| above =

| group1 = Branches | list1 =

{{Navbox|child

| bodyclass = hlist

| group1 = Human | list1 =

- Agricultural

- Behavioral

- Cultural

- Development

- Economic

- Health

- Historical

- Political

- Population

- Settlement

| group2 = Physical | list2 =

- Biogeography

- Coastal / Oceanography

- Earth science

- Earth system science

- Geomorphology / Geology

- Glaciology

- [[Earth:HydrologHydrology / Limnology

- Pedology (Edaphology/Soil science)

- Quaternary science

| group3 = Integrated | list3 =

}}

| group2 = Techniques and tools | list2 =

| group3 = Institutions | list3 =

- Geographic data and information organizations

- Geographical societies

- Geoscience societies

- National mapping agency

| group4 = Education | list4 =

| below =

}}