Biology:Black-crowned night heron

| Black-crowned night heron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-crowned night-heron at a rookery in Cape May County, New Jersey | |

| File:Nycticorax nycticorax - Black-crowned Night Heron - XC99573.ogg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Nycticorax |

| Species: | N. nycticorax

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nycticorax nycticorax | |

| |

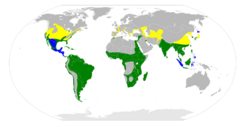

| Range of N. nycticorax Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ardea nycticorax Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), or black-capped night-heron, commonly shortened to just night-heron in Eurasia, is a medium-sized heron found throughout a large part of the world, including parts of Europe, Asia, and North and South America. In Australasia it is replaced by the closely related nankeen night-heron (N. caledonicus), with which it has hybridized in the area of contact.

Taxonomy and name

The black-crowned night-heron was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae. He placed it with herons, cranes and egrets in the genus Ardea and coined the binomial name Ardea nicticorax.[1] It is now placed in the genus Nycticorax that was introduced in 1817 by the English naturalist Thomas Forster for this species.[2][3] The epithet nycticorax is from Ancient Greek and combines nux, nuktos meaning "night" and korax meaning "raven". The word was used by authors such as Aristotle and Hesychius of Miletus for a "bird of ill omen", perhaps an owl. The word was used by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner in 1555 and then by subsequent authors for a black-crowned night-heron.[4][5]

Four subspecies are recognised:[3]

- N. n. nycticorax (Linnaeus, 1758) – Eurasia south to Africa and Madagascar and east to east Asia, Philippines and Indonesian Archipelago

- N. n. hoactli (Gmelin, 1789) – south Canada to north Argentina and Chile; Hawaii

- N. n. obscurus (Bonaparte, 1855) – Chile and southwest Argentina

- N. n. falklandicus (Hartert, EJO, 1914) – Falkland Islands

In the Falkland Islands, the bird is called quark, which is an onomatopoeia similar to its name in many other languages, like qua-bird in English, kwak in Dutch and West Frisian, kvakoš noční in Czech, квак in Ukrainian, кваква in Russian, vạc in Vietnamese, kowak-malam in Indonesian, and waqwa in Quechua.

Description

Adults have a black crown and back with the remainder of the body white or grey, red eyes, and short yellow legs. They have pale grey wings and white under parts. Two or three long white plumes, erected in greeting and courtship displays, extend from the back of the head. The sexes are similar in appearance although the males are slightly larger. Black-crowned night-herons do not fit the typical body form of the heron family. They are relatively stocky with shorter bills, legs, and necks than their more familiar cousins, the egrets and "day" herons. Their resting posture is normally somewhat hunched but when hunting they extend their necks and look more like other wading birds.

Immature birds have dull grey-brown plumage on their heads, wings, and backs, with numerous pale spots. Their underparts are paler and streaked with brown. The young birds have orange eyes and duller yellowish-green legs. They are very noisy birds in their nesting colonies, with calls that are commonly transcribed as quok or woc.

Measurements:[6]

- Length: 22.8–26 in (58–66 cm)

- Weight: 25.6–35.8 oz (726–1,015 g)

- Wingspan: 45.3–46.5 in (115–118 cm)

Distribution

The breeding habitat is fresh and salt-water wetlands throughout much of the world. The subspecies N. n. hoactli breeds in North and South America from Canada as far south as northern Argentina and Chile , N. n. obscurus in southernmost South America, N. n. falklandicus in the Falkland Islands, and the nominate race N. n. nycticorax in Europe, Asia and Africa. Black-crowned night-herons nest in colonies on platforms of sticks in a group of trees, or on the ground in protected locations such as islands or reedbeds. Three to eight eggs are laid.

This heron is migratory in the northernmost part of its range, but otherwise resident (even in the cold Patagonia). The North American population winters in Mexico, the southern United States, Central America, and the West Indies, and the Old World birds winter in tropical Africa and southern Asia.

A colony of the herons has regularly summered at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. for more than a century.[7] The birds also prominently live year-round in the shores around the San Francisco Bay, with the largest rookery in Oakland.[8] Their ever presence at Oakland's Lake Merritt and throughout the city's downtown area, as well as their resilience to the urban environment and displacement efforts, have led to them being named Oakland's official city bird.[8]

Status in Great Britain

There are two archaeological specimens of the black-crowned night-heron in Great Britain. The oldest is from the Roman London Wall and the more recent from the Royal Navy's late medieval victualling yards in Greenwich.[9] It appears in the London poulterers' price lists as the Brewe, a bird which was thought to have been the Eurasian whimbrel or glossy ibis, which has now been shown to refer to the black-crowned night-heron, derived from the medieval French Bihoreau.[10] Black-crowned night-heron may have bred in the far wetter and wider landscape of pre-modern Britain. They were certainly imported for the table so the bone specimens themselves do not prove they were part of the British avifauna. In modern times the black-crowned night-heron is a vagrant and feral breeding colonies were established at Edinburgh Zoo from 1950 into the 21st century[11] and at Great Witchingham in Norfolk, where there were 8 pairs in 2003 but breeding was not repeated in 2004 or 2005.[12] A pair of adults were seen with two recently fledged juveniles in Somerset in 2017, which is the first proven breeding record of wild black-crowned night-herons in Great Britain.[13]

Behaviour

These birds stand still at the water's edge and wait to ambush prey, mainly at night or early morning. They primarily eat small fish, leeches, earthworms, mussels, squid,[14] crustaceans (such as crayfish),[14] frogs, other amphibians,[14] aquatic insects, terrestrial insects, lizards, snakes,[14] small mammals (such as rodents),[14] small birds, eggs, carrion, plant material, and garbage and refuse at landfills.[14] They are among the seven heron species observed to engage in bait fishing; luring or distracting fish by tossing edible or inedible buoyant objects into water within their striking range – a rare example of tool use among birds.[15][16] During the day they rest in trees or bushes. N. n. hoactli is more gregarious outside the breeding season than the nominate race.

Parasites

A thorough study performed by J. Sitko and P. Heneberg in the Czech Republic in 1962–2013 suggested that the central European black-crowned night-herons host 8 helminth species. The dominant species consisted of Neogryporhynchus cheilancristrotus (62% prevalence), Contracaecum microcephalum (55% prevalence) and Opistorchis longissimus (10% prevalence). The mean number of helminth species recorded per host individual reached 1.41. In Ukraine, other helminth species are often found in black-crowned night-herons too, namely Echinochasmus beleocephalus, Echinochasmus ruficapensis, Clinostomum complanatum and Posthodiplostomum cuticola.[17]

Gallery

Wading, Arches National Park, Utah

juvenile in flight, Cyprus

adult in flight, Cyprus

Eating a goldfish, Toronto

References

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1758) (in Latin). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. pp. 142–143. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/727049.

- ↑ Forster, T. (1817). A Synoptical Catalogue of British Birds; intended to identify the species mentioned by different names in several catalogues already extant. Forming a book of reference to Observations on British ornithology. London: Nichols, son, and Bentley. p. 59. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/13330976.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds (2023). "Ibis, spoonbills, herons, Hamerkop, Shoebill, pelicans". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. https://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/pelicans/.

- ↑ Gesner, Conrad (1555) (in Latin). Historiae animalium liber III qui est de auium natura. Adiecti sunt ab initio indices alphabetici decem super nominibus auium in totidem linguis diuersis: & ante illos enumeratio auium eo ordiné quo in hoc volumine continentur. Zurich: Froschauer. pp. 602–603. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/52661484.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. https://archive.org/stream/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling#page/n277/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Black-crowned Night-Heron Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology" (in en). https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Black-crowned_Night-Heron/id.

- ↑ Akpan, Nsikan (12 May 2015). "Smithsonian's mystery of the black-crowned night-herons solved by satellites". PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/sciencescope-smithsonians-mystery-black-crowned-night-herons-solved-satellites/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Oakland Has Its First Official Bird Thanks to These Dedicated Kids" (in en). 2019-05-24. https://www.audubon.org/news/oakland-has-its-first-official-bird-thanks-these-dedicated-kids.

- ↑ D.W. Yalden; U. Albarella (2009). The History of British Birds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-958116-0.

- ↑ W.R.P. Bourne (2003). "Fred Stubbs, Egrets, Brewes and climatic change". British Birds 96: 332–339.

- ↑ The Birds of Scotland Volume 1. Scottish Ornithologists' Club. 2007. ISBN 978-0-9512139-0-2.

- ↑ Holling M. and the Rare Breeding Birds Panel (2007) Non-native breeding birds in the United Kingdom 2003, 2004 and 2005 British Birds 100 638–649

- ↑ "Night-Herons breed in Somerset - a UK first". Rare Bird Alert. http://www.rarebirdalert.co.uk/v2/Content/Wildlife-Trusts-Night-Herons-breed-in-Somerset-a-UK-first.aspx?s_id=2065125.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 "Nycticorax nycticorax (Black-crowned night-heron)". https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Nycticorax_nycticorax/.

- ↑ Riehl, Christina (2001). "Black-Crowned Night-Heron Fishes with Bait". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 24 (2): 285–286. doi:10.2307/1522044.

- ↑ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Hansell, Michael H. (2011-01-01). "Fishing with a Bait or Lure: A Brief Review of the Cognitive Issues" (in en). Ethology 117 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2010.01848.x. ISSN 1439-0310.

- ↑ Sitko, J.; Heneberg, P. (2015). "Composition, structure and pattern of helminth assemblages associated with central European herons (Ardeidae)". Parasitology International 64 (1): 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2014.10.009. PMID 25449288.

External links

- Blasco-Zumeta, Javier; Heinze, Gerd-Michael. "Black-crowned night-heron". Identification Atlas of Aragon's Birds. http://blascozumeta.com/wp-content/uploads/aragon-birds/non-passeriformes/037.nightheron-nnycticorax.pdf.

- Black-crowned Night-Heron Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Black-crowned night-heron - Nycticorax nycticorax - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

Wikidata ☰ Q126216 entry

|