Biology:Desmatosuchus

| Desmatosuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

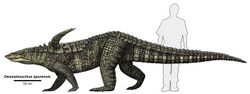

| Desmatosuchus from Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Archosauria/Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Order: | †Aetosauria |

| Family: | †Stagonolepididae |

| Subfamily: | †Desmatosuchinae |

| Genus: | †Desmatosuchus Case, 1920 |

| Type species | |

| †Desmatosuchus spurensis Case, 1921

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Desmatosuchus (/dɛzmætoʊsuːkəs/, from Greek δεσμός desmos 'link' + σοῦχος soûkhos 'crocodile') is an extinct genus of archosaur belonging to the Order Aetosauria. It lived during the Late Triassic.

Description

Desmatosuchus was a large quadrupedal reptile measuring 4.5 m (15 ft) to over 5 m (16 ft) long and weighing about 280–300 kg (620–660 lb).[2][3][4][5] Its vertebral column had amphicoelus centra and 3 sacral vertebrae. This archosaur's most distinguishing anatomical characteristics were its scapulae which possessed large acromion processes commonly referred to as "shoulder spikes".[2] The forelimbs were much shorter than the hindlimbs, with humeri less than two-thirds the length of the femurs.[6] The pelvic girdle consisted of a long pubis with a strong symphysis in the middle, a plate-like ischium, a highly recurved ilium, and a deep, imperforate acetabulum.[6] The femurs were relatively long and straight, the ankles crurotarsal, with calcaneal tubers that gave it large heels.[6]

Its skull was relatively small, on average about 37 centimeters long, 18 centimeters wide, and 15 centimeters high. The braincase was very firmly fused with the skull roof and palate. It had slender, forked premaxillae that turned up and expanded in the front, creating a shovel-like structure.[2] Desmatosuchus is unique among aetosaurs in that its species are the only known aetosaurs that lacked teeth on their premaxillae.[2] Their premaxillae fit loosely together with their maxillae, indicating flexibility at that joint.[2] Their maxilla contained 10 to 12 teeth.[2] Desmatosuchus also had very thin vomers, which bounded the medial side of the internal nares.[2] These internal nares were relatively large, roughly half the length of the entire palate.[2] The lower jaw typically carried 5 or 6 teeth, and had a toothless beak on the end.[2] The dentary was about half the length of the lower jaw, with the front portion being toothless and covered by a horny sheath.[2] Behind the dentary was a moderately large mandibular fenestra.

Individuals of Desmatosuchus were heavily armored. The carapace was made up of two rows of median scutes surrounded by two more rows of lateral scutes. The lateral scutes had well-developed spine-like processes which pointed out laterally and dorso-posteriorly.[7] There were typically five rows of spines, increasing in size anteriorly. The front spine was much larger, around 28 centimeters long, and was recurved. The fourth spine varies in length in each specimen, but remains shorter than the fifth in all of them.[2] Desmatosuchus are the only aetosaurs known to have possessed spines like these.[7]

Discovery and classification

The first Desmatosuchus discovery occurred in the late 19th century when E.D. Cope classified armor from the Dockum Group in Texas , USA, as the new species Episcoposaurus haplocerus.[8] Case later classified a partial skeleton found in the Tecovas Formation as Desmatosuchus spurensis.[9] Since the localities of Cope and Case were only a few kilometers apart, the two taxa were synonymized into Desmatosuchus haplocerus, the initial type species of the genus.[8]

A revision of Desmatosuchus by Parker (2008) found the lectotype of Episcoposaurus haplocerus to be referable to Desmatosuchus but indeterminate at the species level. Therefore, E. haplocerus was considered to be a nomen dubium and D. spurensis was named the type species of the genus. Two species were accepted as valid: D. spurensis and D. smalli, named after Brian J. Small for his contribution to the study of this genus.[10] Desmatosuchus chamaensis is recognized as a distinct genus, but there is some dispute about whether the name Heliocanthus or Rioarribasuchus applies.[8]

The following cladogram is simplified, after an analysis presented by Julia B. Desojo, Martin D. Ezcurra and Edio E. Kischlat (2012).[11]

| Aetosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Bones and armor pieces of Desmatosuchus are abundant in the Dockum formation, Chinle formation, and Post quarry, indicating that they were widespread and abundant during the Late Triassic.[2] It is possible that Desmatosuchus traveled in herds or family units. This is evidenced by several findings of multiple Desmatosuchus skeletons in relatively small areas.[2]

Desmatosuchus had blunt, bulbous, slightly recurved teeth. Furthermore, they are believed to have had homodont dentition.[2] This, combined with its shovel like snout, indicate that Desmatosuchus fed by digging up soft vegetation.[7] This method of feeding is further evidenced by its toothless premaxilla and dentary tip, which were covered in horny sheaths. These sheaths protected the bones and could be used for cutting or holding objects.[12] It is believed that Desmatosuchus dug for food in the soft mud near bodies of water due to the abundance of lakes and rivers in the Dockum area and the fact that Desmatosuchus scutes are often found among parts of other reptiles that are known to have fed along waterways.[2] It is unknown whether or not Desmatosuchus replaced their teeth and, if so, how. The low number of Desmatosuchus teeth that have been discovered indicates that they were only held in place by soft tissue connections.[2] The jaw articulation point is below the tooth line, holding its upper and lower tooth rows parallel while biting in a way that is reminiscent of ornithischian dinosaurs.[12]

The armor and spikes of Desmatosuchus were its only ways to defend itself from predators. The lateral spike rows showed variation in size among individuals, especially the second most anterior spike. This spike was always shorter than the one in front of it, but to what extent varied drastically. This variation may indicate sexual dimorphism.[7] It has also been hypothesized as a form of sexual display.[2] Aside from this armor, Desmatosuchus was defenseless from attacks from carnivores. Several Desmatosuchus bones have been found amongst skeletons of Postosuchus, indicating predation by Postosuchus.[2] The herd nature of Desmatosuchus apparently did little to discourage predators, as Postosuchus along with several other Late Triassic carnivores also traveled in groups.[2]

Most thecodonts of the Late Triassic lacked certain pelvic features that aided locomotion, such as a deep acetabulum or a crest over the acetabulum. This, in spite of their upright posture, rendered them only slightly more mobile than sprawling reptiles.[13] Desmatosuchus possessed both of these features, along with its long femur and elongate pubis, making it more mobile than most thecodonts of its time.[13] This mobility, along with its size, abundance, and specialized beak made it the chief herbivore in the Dockum area.[2]

It has also been suggested that Desmatosuchus could have been omnivorous or even an insectivore. This is because of several similarities between Desmatosuchus and armadillos.[14] For instance, both groups are armored. They possess long snouts that lack teeth on the end. Also, there is evidence of bees, wasps, and termites in the Late Triassic, meaning that Desmatosuchus had access to insects that armadillos prey on.[14] Their teeth are somewhat similar in shape, although armadillos have more peg-like teeth.[14] Both Desmatosuchus and armadillos typically carry around 6 teeth on their dentaries. Both armadillos and Desmatosuchus have hypertrophied processes present on their limb bones, which indicates large limb muscles.[14] This connection is more tenuous, however, since Desmatosuchus have a crest over their hind limbs but lack one on their forelimbs, meaning that they likely didn't have the musculature for digging with their forelimbs the way armadillos do. In spite of these parallels, the general consensus is still that Desmatosuchus was most likely herbivorous.[2] [13]

References

- ↑ Parker, William G. (June 2005). "A new species of the Late Triassic aetosaur Desmatosuchus (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia)". Comptes Rendus Palevol 4 (4): 327–340. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.03.002.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 Small, Bryan John (December 1985). The Triassic thecodontian reptile Desmatosuchus: osteology and relationships (Masters thesis). Texas Tech University. hdl:2346/19710.

- ↑ von Baczko, M. B., Desojo, J. B., Gower, D. J., Ridgely, R., Bona, P., & Witmer, L. M. (2021). New digital braincase endocasts of two species of Desmatosuchus and neurocranial diversity within Aetosauria (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia). The Anatomical Record, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24798

- ↑ Julia Brenda Desojo, Randall B. Irmis, Sterling J. Nesbitt (2013). Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and Their Kin. Geological Society. pp. 224. ISBN 9781862393615. https://books.google.com/books?id=TN_KBP3vxg4C. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Parker, William G.; Reyes, William A.; Marsh, Adam D. (2023-11-08). "Incongruent ontogenetic maturity indicators in a Late Triassic archosaur (Aetosauria: Typothorax coccinarum )" (in en). The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25343. ISSN 1932-8486. https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25343.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Charig, Alan J. (1972). "The evolution of the archosaur pelvis and hindlimb: an explanation in functional terms". in Joysey, Kenneth A.; Kemp, Thomas S.. Studies in Vertebrate Evolution. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 121–155. ISBN 978-0050021316. OCLC 844318914.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Palmer, D., ed (1999). "The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals". The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 96. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Parker, William G. (March 2007). "Reassessment of the aetosaur "Desmatosuchus" chamaensis with a reanalysis of the phylogeny of the Aetosauria (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5 (1): 41–68. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001994.

- ↑ Gregory, Joseph T. (3 June 1953). "Typothorax and Desmatosuchus". Postilla (Yale Peabody Museum) 16: 1–27. http://peabody.yale.edu/sites/default/files/documents/scientific-publications/ypmP016_1953.pdf.

- ↑ Parker, William G. (12 May 2008). "Description of new material of the aetosaur Desmatosuchus spurensis (Archosauria: Suchia) from the Chinle Formation of Arizona and a revision of the genus Desmatosuchus". PaleoBios (University of California Museum of Paleontology) 28 (1): 1–40. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/science/paleobios/abstracts_26to30.php#pb281.

- ↑ Desojo, Julia B.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Kischlat, Edio E. (2012). "A new aetosaur genus (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the early Late Triassic of southern Brazil". Zootaxa 3166: 1–33. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3166.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334. http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2012/f/z03166p033f.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Walker, A. D. (31 August 1961). "Triassic reptiles from the Elgin area: Stagonolepis, Dasygnathus and their allies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 244 (709): 103–204. doi:10.1098/rstb.1961.0007. Bibcode: 1961RSPTB.244..103W.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Bakker, R. T. (December 1971). "Dinosaur physiology and the origin of mammals". Evolution 25 (4): 636–658. doi:10.2307/2406945. PMID 28564788.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Small, Bryan J. (September 2002). "Cranial anatomy of Desmatosuchus haplocerus (Reptilia: Archosauria: Stagonolepididae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00028.x.

Wikidata ☰ Q132727 entry

|