Biology:Suminia

| Suminia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil skeleton, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Genus: | †Suminia Ivachnenko, 1994[1] |

| Species: | †S. getmanovi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Suminia getmanovi Ivachnenko, 1994

| |

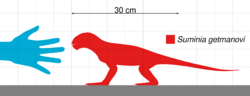

Suminia is an extinct genus of basal anomodont that lived during the Tatarian age of the late Permian, spanning approximately from 268-252 Ma.[2] Suminia is recognized the youngest non-dicynodont anomodont.[1] Its fossil localities are primarily derived from the Kotel’nich locality of the Kirov Oblast in Russia . However, there have been some isolated specimen found in a few different localities, all from eastern European regions of Russia.[3]

Suminia, along with Otsheria and Ulemica make up the monophyletic group of Russian basal anomodonts named Venyukovioidea.[4] These Venyukovioid anomodonts are understood to have been derived from an ancestor that dispersed from Gondwana into Euramerica.[5] Suminia getmanovi is the only defined species within the genus and it is known for specializations in teeth for effective, functional oral processing of plant material as well as being one of the first species with a proposed arboreal lifestyle.[6]

Discovery

New material of Suminia was recently excavated from the Upper Permian Kotel’nich locality in which a single large block with articulated skeletons of at least 15 specimen of Suminia getmanovi was found. This new material of Suminia getmanovi consisted of mainly subadult to adult specimen that were well preserved (no signs of weathering or predation), suggesting rapid burial perhaps due to a catastrophic event.[6]

Description

Suminia are diagnosed as a small Venyukoviid with various autapomorphies such as large orbit (almost 1/3 of the skull length), large teeth in relation to the skull size, reduced number of 23 presacral vertebrae, a more long than wide cervical vertebrae (suggests elongated neck), elongated limbs, manus and pes equal to ~40% of length of their respective limb, and enlarged distal carpal 1 and tarsal 1.[3]

Cranial anatomy

Suminia getmanovi are recognized for their well-preserved skulls and teeth.[7][6] Suminia skull length is fairly small, measuring in at 58mm long characterized with a short snout with its squamosal regions expanded. While the orbit composes of around 27% of the total skull length, the external naris is also large, measured to compose of about 13% of the total skull length.[2] Cranial features that are only shared with Ulemica that distinguish Suminia and Ulemica from other anomodonts is the preparietal absence, a reduced interparietal suture located anterior to the pineal foramen, and narrow palatine.[2] Suminia cranial anatomy can also be defined by their raised pineal foramen (in comparison with other taxa with flush pineal foramen to skull) and premaxilla contact with palatine which are all features shared by its infraorder, Venyukovioidea.[2] Perhaps one of the most striking cranial anatomy feature of Suminia is its similarity in masticatory architecture with dicynodonts, indicating that the sliding jaw articulation may have originated before dicynodonts. Suminia dentition have significant implications on its feeding ecology which is discussed below.[2][7]

Post cranial anatomy

Study into Suminia post cranial anatomy reveal many autapomorphies for the single specimen. Significant post cranial autapomorphies of Suminia are the reduced number of presacral and dorsal vertebrae (exclusively amphicoelous) with lack of fusion in the sacral region between vertebrae (suggests high flexibility), wide pre- and postzygapophyses, longer proportions of cervical pleurocentra, distinct proportionally longer limbs, a manus that forms ~ 40% of the length of the forelimb with particularly long, curved terminal phalanges, a pes that makes up ~38% of the hindlimb, and enlarged carpal 1 and tarsal 1 (suggests divergent first digit).[3][6] These different morphological features indicate a significantly deviated post cranial anatomy from other anomodonts, suggesting that Suminia adopted an arboreal lifestyle (see below).[3][6]

Feeding ecology

In combination with a masticatory architecture similar to Dicynodonts (defined by sliding jaw articulation) Suminia’s canineless, large leaf shaped teeth follow occluding dentition that is completely marginal which differs from other species with leaf-shaped teeth present. This provides indications not only for herbivory, but into the mechanisms of oral processing.[4][7][8] One interesting feature of the occlusal pattern in Suminia dentition is the angle of the occluding surfaces. With an angle of 75 degrees from jaw plane, it is suggested that Suminia’s more posterior shreds food material rather than crush it. The anterior teeth are observed to be significantly larger and devoid of this occlusial pattern. Therefore, the more anterior teeth are suggested to be responsible for cutting off pieces of plant for the posterior teeth to shred.[2][7] Suminia are therefore understood to have been obligatory herbivores as the dentition and mandibular function permits shredding of plant material via posterior translation.[7]

Teeth replacement was discovered to be infrequent which was shown in certain specimen of Suminia getmanovi that were seen to have teeth worn down almost to the neck.[4] However, these wear facets on the upper and lower posterior teeth are in themselves, consistent with herbivory in that the locations of the wear (labial and lingual aspects of upper and lower posterior teeth respectively), are distinct evidence that the wear isn't a consequence of tooth-to-food but rather tooth-to-tooth occlusion.[9] The evidence for Suminia’s extensive oral processing suggest that Suminia dentition is highly specialized for high fiber herbivory. This provides an alternative explanation that the ability to process tough, high fiber plant material may have been a more basal feature of anomodonts than previously thought.[7][9]

Habitat/lifestyle

Adaptations to arboreal lifestyle are understood to evolve through convergent evolution. However, many arboreal vertebrates share similar physical mechanisms (grasping, clinging, hooking)[10]

Suminia is referred to as the earliest known arboreal tetrapod due to the suggested grasping abilities inferred from the notably enlarged and phalangiform carpal 1 and tarsal 1 which indicate that they possess a divergent first digit, capable of grasping. The first digit is measured to have an angle of ~30-40 degrees to the remaining digits of the manus and pes which grants ability of the first digit to flex ventrally, independent of the rest of the digits (can be compared to an opposable thumb)[3][6] This is further supported by the elongated limbs and claw shaped, laterally compressed terminal phalanges which would aid in clinging ability. In addition, the tail anatomy with expansion of the anterior region and suggests ability of balance as well as prehensile, grasping abilities, providing more evidence for arboreal lifestyle.[3][6]

Via a morphometric analysis as well as comparison to other arboreal vertebrates, Suminia getmanovi provides anatomical evidence that it lived among the trees, stamping a significant mark in evolutionary history for arboreal lifestyle.[3][6]

Classification

Suminia belong to the monophyly/infraorder Venyukovioidea, a sub clade of basal anomodonts.

| 1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of therapsids

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ivachnenko MF. 1994. A new Late Permian dromasaurian (Anomodontia) from Eastern Europe. Paleontological Journal 28: 96- 103.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Rybczynski N. 2000. Cranial anatomy and phylogenetic position of Suminia getmanovi, a basal anomodont (Amniota: Therapsida) from the Late Permian of Eastern Europe. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 130:329–73

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Fröbisch, J. and Reisz, R. R. 2011. The postcranial anatomy of Suminia getmanovi (Synapsida: Anomodontia), the earliest known arboreal tetrapod. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 162: 661–698.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Modesto, S. & B. Rubidge (2000) A basal anomodont therapsid from the lower Beaufort Group, Upper Permian of South Africa, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20:3, 515-521.

- ↑ Modesto, S. P., B. S. Rubidge, and J. Welman. 1999. The most basal anomodont therapsid and the primacy of Gondwana in the evolution of the anomodonts. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266:331–337.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Fröbisch, J. and Reisz, R. R. 2009. The Late Permian herbivore Suminia and the early evolution of arboreality in terrestrial vertebrate ecosystems. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 276: 3611–3618.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Reisz, Robert R. (2006). "Origin of dental occlusion in tetrapods: signal for terrestrial vertebrate evolution?". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 306B (3): 261–277. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21115.

- ↑ Ivakhnenko, M.F. Cranial morphology and evolution of Permian Dinomorpha (Eotherapsida) of eastern Europe. Paleontol. J. 42, 859–995 (2008).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rybczynski, N. & Reisz, R. R. 2001 Earliest evidence for efficient oral processing in a terrestrial herbivore. Nature 411, 684 –687.

- ↑ Hildebrand, M. & Goslow, G. E. J. 2001 Analysis of vertebrate structure, 5th edn. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Wikidata ☰ Q135229 entry

|