Biology:Oriental magpie-robin

| Oriental magpie-robin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male C. s. ceylonensis, Sri Lanka | |

| |

| Female C. s. saularis, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Muscicapidae |

| Genus: | Copsychus |

| Species: | C. saularis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Copsychus saularis | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gracula saularis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The Oriental magpie-robin (Copsychus saularis) is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family Turdidae, but now considered an Old World flycatcher. They are distinctive black and white birds with a long tail that is held upright as they forage on the ground or perch conspicuously. Occurring across most of the Indian subcontinent and parts of Southeast Asia, they are common birds in urban gardens as well as forests. They are particularly well known for their songs and were once popular as cagebirds.

The oriental magpie-robin is considered the national bird of Bangladesh.

Description

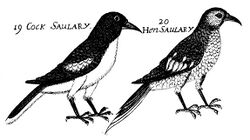

This species is 19 centimetres (7.5 in) long, including the long tail, which is usually held cocked upright when hopping on the ground. When they are singing a song the tail is normal like other birds. It is similar in shape to the smaller European robin, but is longer-tailed. The male has black upperparts, head and throat apart from a white shoulder patch. The underparts and the sides of the long tail are white. Females are greyish black above and greyish white under. Young birds have scaly brown upperparts and head.

The nominate race is found on the Indian subcontinent and the females of this race are the palest. The females of the Andaman Islands race andamanensis are darker, heavier-billed and shorter-tailed. The Sri Lankan race ceylonensis (formerly included with the peninsular Indian populations south of the Kaveri River)[2] and southern nominate individuals have the females nearly identical to the males in shade. The eastern populations, the ones in Bangladesh and Bhutan, have more black on the tail and were formerly named erimelas.[3] The populations in Myanmar (Burma) and further south are named as the race musicus.[4] A number of other races have been named across the range, including prosthopellus (Hong Kong), nesiotes, zacnecus, nesiarchus, masculus, pagiensis, javensis, problematicus, amoenus, adamsi, pluto, deuteronymus and mindanensis.[5] However, many of these are not well-marked and the status of some of them is disputed.[6] Some, like mindanensis, have now been usually recognized as full species (the Philippine magpie-robin).[7] There is more geographic variation in the plumage of females than in that of the males.[8]

It is mostly seen close to the ground, hopping along branches or foraging in leaf-litter on the ground with a cocked tail. Males sing loudly from the top of trees or other high perches during the breeding season.[3]

Etymology

The Indian name of dhyal or dhayal has led to many confusions. It was first used by Eleazar Albin ("dialbird") in 1737 (Suppl. N. H. Birds, i. p. 17, pls. xvii. xviii.), and Levaillant (Ois. d'Afr. iii. p. 50) thought it referred to a sun dial and he called it Cadran. Thomas C. Jerdon wrote (B. India, ii. p. 1l6) that Linnaeus,[9] thinking it had some connection with a sun-dial, called it solaris, by lapsus pennae, saularis. This was, however, identified by Edward Blyth as an incorrect interpretation and that it was a Latinization of

the Hindi word saulary which means a "hundred songs". A male bird was sent with this Hindi name from Madras by surgeon Edward Bulkley to James Petiver, who first described the species (Ray, Synops. Meth. Avium, p. 197).[10][11]

Distribution and habitat

This magpie-robin is a resident breeder in tropical southern Asia from Nepal, Bangladesh, India , Sri Lanka and eastern Pakistan , eastern Indonesia, Thailand, south China , Malaysia, and Singapore.[3]

The Oriental magpie-robin is found in open woodland and cultivated areas often close to human habitations.

Behaviour and ecology

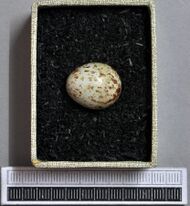

Magpie-robins breed mainly from March to July in India and January to June in south-east Asia. Males sing from high perches during courtship. The display of the male involves puffing up the feathers, raising the bill, fanning the tail and strutting.[2] They nest in tree hollows or niches in walls or building, often adopting nest boxes. They line the cavity with grass. The female is involved in most of the nest building, which happens about a week before the eggs are laid. Four or five eggs are laid at intervals of 24 hours and these are oval and usually pale blue green with brownish speckles that match the color of hay. The eggs are incubated by the female alone for 8 to 14 days.[12][13] The nests are said to have a characteristic odour.[citation needed]

Females spend more effort on feeding the young than males. Males are quite aggressive in the breeding season and will defend their territory.[14] They respond to the singing of intruders and even their reflections.[15] Males spend more time on nest defense.[16] Studies of the bird song show dialects[17] with neighbours varying in their songs. The calls of many other species may be imitated as part of their song.[18][19] This may indicate that birds disperse and are not philopatric.[20] Females may sing briefly in the presence of a male.[21] Apart from their song, they use a range of calls including territorial calls, emergence and roosting calls, threat calls, submissive calls, begging calls and distress calls.[22] The typical mobbing calls is a harsh hissing krshhh.[2][3][23]

The diet of magpie-robins includes mainly insects and other invertebrates. Although mainly insectivorous, they are known to occasionally take flower nectar, geckos,[24][25] leeches,[26] centipedes[27] and even fish.[28]

They are often active late at dusk.[3] They sometimes bathe in rainwater collected on the leaves of a tree.[29]

Status

This species is considered one of "least concern" globally, but in some areas it is declining.

In Singapore they were common in the 1920s, but declined in the 1970s, presumably due to competition from introduced common mynas.[30] Poaching for the pet bird trade and habitat changes have also affected them and they are locally protected by law.[31]

This species has few avian predators. Several pathogens and parasites have been reported. Avian malaria parasites have been isolated from the species,[32] while H4N3[33] and H5N1 infection has been noted in a few cases.[34] Parasitic nematodes of the eye have been described.[35]

In culture

Oriental magpie-robins were widely kept as cage birds for their singing abilities and for fighting in India in the past.[36] They continue to be sold in the pet trade in parts of Southeast Asia.

Aside from being recognized as the national bird of the country, in Bangladesh, the oriental magpie-robin is common and known as the doyel or doel (দোয়েল).[37] Professor Kazi Zakir Hossain of Dhaka University proposed to consider the Magpie Robin birds as the national bird of Bangladesh. The reasoning behind this is the Magpie Robin can be seen everywhere in towns and villages across the country. In that context, the Magpie Robin (doel) bird was declared as the national bird of Bangladesh.[38] It is a widely used symbol in Bangladesh, appearing on a currency note, and a landmark in the city of Dhaka is named as the Doel Chattar (meaning: Doel Square).[39][40]

In Sri Lanka, this bird is called Polkichcha.[41]

In southern Thailand, this bird is known locally as Binlha (Thai: บินหลา — with another related bird, the white-rumped shama). They are frequently mentioned in contemporary songs.[42]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International. (2017). "Copsychus saularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T103893432A111178145. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T103893432A111178145.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/103893432/111178145. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ali, S; S D Ripley (1997). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 8 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 243–247. ISBN 978-0-19-562063-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Rasmussen PC; JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 395.

- ↑ Baker, ECS (1921). "Handlist of the birds of the Indian empire". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 27 (4): 87–88. https://archive.org/details/handlistofgenera00bake.

- ↑ Ripley, S D (1952). "The thrushes". Postilla 13: 1–48. https://archive.org/stream/postilla150peab#page/n103/mode/2up.

- ↑ Hoogerwerf, A (1965). "Notes on the taxonomy of Copsychus saularis with special reference to the subspecies amoenus and javensis". Ardea 53: 32–37. http://ardeajournal.natuurinfo.nl/ardeapdf/a53-032-037.pdf.

- ↑ "Phylogeography of the magpie-robin species complex (Aves: Turdidae: Copsychus) reveals a Philippine species, an interesting isolating barrier and unusual dispersal patterns in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia". Journal of Biogeography 36 (6): 1070–1083. 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02087.x. http://www.kevinwinker.org/Sheldon%20et%20al%20Copsychus%20J%20Biogeogr%202009.pdf.

- ↑ Baker, ECS (1924). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. 2 (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 112–116. https://archive.org/stream/BakerFbiBirds2/bakerFBI2#page/n137/mode/1up.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1760). Systema naturae. Halae Magdeburgicae : Typis et sumtibus Io. Iac. Curt.. https://archive.org/stream/carolilinnaeisys11linn#page/n232/mode/1up/.

- ↑ Blyth E. (1867). "The Ornithology of India. - A commentary on Dr. Jerdon's 'Birds of India'". Ibis 3 (9): 1–48. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1867.tb06417.x. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/partpdf/17464.

- ↑ Newton, Alfred (1893–1896). A Dictionary of Birds. Adam & Charles Black, London. p. 133. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofbird00newt.

- ↑ Pillai, NG (1956). "Incubation period and 'mortality rate' in a brood of the Magpie-Robin [Copsychus saularis (Linn.)"]. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 54 (1): 182–183. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48182822.

- ↑ Hume, A.O. (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian birds. 2 (2nd ed.). R H Porter, London. pp. 80–85. https://archive.org/stream/nestseggsofindia02humerich#page/80/mode/2up.

- ↑ Narayanan E. (1984). "Behavioural response of a male Magpie-Robin (Copsychus saularis Sclater) to its own song". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 81 (1): 199–200. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48874107.

- ↑ Cholmondeley, EC (1906). "Note on the Magpie Robin (Copsychus saularis)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 17 (1): 247. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/30119415.

- ↑ Sethi, Vinaya Kumar; Bhatt, Dinesh (2007). "Provisioning of young by the Oriental Magpie-robin". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119 (3): 356–360. doi:10.1676/06-105.1.

- ↑ Aniroot Dunmak; Narit Sitasuwan (2007). "Song Dialect of Oriental Magpie-robin (Copsychus saularis) in Northern Thailand". The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University 7 (2): 145–153. https://thaiscience.info/Journals/Article/NHCU/10439775.pdf.

- ↑ Neelakantan, KK (1954). "The secondary song of birds.". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 52 (3): 615–620. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48184508.

- ↑ Law, SC (1922). "Is the Dhayal Copsychus saularis a mimic?". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 28 (4): 1133. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/52170795.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, H.; J. Cirillo; B.R. Subba; D. Todt (2007). "Song Performance Rules in the Oriental Magpie Robin (Copsychus salauris)" (PDF). Our Nature 5: 1–13. doi:10.3126/on.v5i1.791. http://www.nepjol.info/index.php/ON/article/viewFile/791/760.

- ↑ Kumar, Anil; Bhatt, Dinesh (2002). "Characteristics and significance of song in female Oriental Magpie-Robin, Copysychus saularis.". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 99 (1): 54–58. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48603891.

- ↑ Kumar, A.; Bhatt, D. (2001). "Characteristics and significance of calls in Oriental magpie robin". Curr. Sci. 80: 77–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24105559.

- ↑ Bonnell, B (1934). "Notes on the habits of the Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis saularis Linn.". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 37 (3): 729–730. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48733223.

- ↑ Sumithran, Stephen (1982). "Magpie-Robin feeding on geckos". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 79 (3): 671. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48745119.

- ↑ Saxena, Rajiv (1998). "Geckos as food of Magpie Robin". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 95 (2): 347. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48604889.

- ↑ Karthikeyan, S (1992). "Magpie Robin preying on a leech". Newsletter for Birdwatchers 32 (3&4): 10.

- ↑ Kalita, Simanta Kumar (2000). "Competition for food between a Garden Lizard Calotes versicolor (Daudin) and a Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis Linn.". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 97 (3): 431.

- ↑ Sharma, Satish Kumar (1996). "Attempts of female Magpie Robin to catch a fish". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 93 (3): 586. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48603860.

- ↑ Donahue, Julian P (1962). "The unusual bath of a Lorikeet [Loriculus vernalis (Sparrman) and a Magpie-Robin [Copsychus saularis (Linn.)]"]. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 59 (2): 654. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/47855357.

- ↑ "Status of the Oriental Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis in Singapore". Malay Nat. J. 50: 347–354. 1997.

- ↑ Yap, Charlotte A. M.; Navjot S. Sodhi (2004). "Southeast Asian invasive birds: ecology, impact and management". Ornithological Science 3: 57–67. doi:10.2326/osj.3.57.

- ↑ Ogaki, M. (1949). "Bird Malaria Parasites Found in Malay Peninsula.". Am. J. Trop. Med. 29 (4): 459–462. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1949.s1-29.459. PMID 18153046.

- ↑ Dennis J. Alexander (1992). Avian Influenza in the Eastern Hemisphere 1986-1992. Avian Diseases 47. Special Issue.. Third International Symposium on Avian Influenza. 1992 Proceedings.. pp. 7–19.

- ↑ Quarterly Epidemiology Report Jan-Mar 2006. Hong Kong Government. 2006. http://www.afcd.gov.hk/english/quarantine/qua_vetlab/qua_vetlab_ndr/qua_vetlab_ndr_adr/files/qer010306.pdf.

- ↑ Sultana, Ameer (1961). "A Known and a New Filariid from Indian Birds". The Journal of Parasitology 47 (5): 713–714. doi:10.2307/3275453. PMID 13918345.

- ↑ Law, Satya Churn (1923). Pet birds of Bengal. Thacker, Spink & Co. https://archive.org/details/petbirdsofbengal00laws.

- ↑ "Doel is the mascot" (in en). The Daily Star. 2009-09-16. http://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-106149.

- ↑ "Introduction to Oriental Magpie Robin". https://www.pettract.com/2020/11/oriental-magpie-robin-details.html.

- ↑ "National Birds" (in en). The Daily Star. 2016-07-23. http://www.thedailystar.net/city/national-birds-1258027.

- ↑ "Fountainous reopening of Doyel Chattar" (in en). The Daily Star. 2016-05-08. http://www.thedailystar.net/city/fountainous-reopening-doyel-chattar-1220323.

- ↑ Anonymous (1998). "Vernacular Names of the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent". Buceros 3 (1): 53–109. http://www.bnhsenvis.nic.in/pdf/vol%203%20(1).pdf.

- ↑ Member number 702999 (2014-04-06). "ทำไมนกบินหลา ถึงพูดถึงในเพลงปักษ์ใต้มีความสำคัญต่อชีวิตชาวใต้อย่างไรครับ" (in thai). Pantip.com. https://pantip.com/topic/31882671. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

Other sources

- Mehrotra, P. N. 1982. Morphophysiology of the cloacal protuberance in the male Copsychus saularis (L.) (Aves, Passeriformes). Science and Culture 48:244–246.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Oriental Magpie Robin videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Magpie-robin in Banglapedia

- Introduction to Oriental Magpie Robin

Wikidata ☰ Q266761 entry

|