Biology:Persoonia linearis

| Narrow-leaved geebung | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Persoonia |

| Species: | P. linearis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Persoonia linearis Andrews[2]

| |

| |

| Range of P. linearis in New South Wales and extending into Victoria in eastern Australia | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

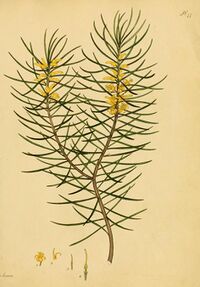

Persoonia linearis, commonly known as the narrow-leaved geebung, is a shrub native to New South Wales and Victoria in eastern Australia. It reaches 3 m (9.8 ft), or occasionally 5 m (16 ft), in height and has thick, dark grey papery bark. The leaves are, as the species name suggests, more or less linear in shape, and are up to 9 cm (3.5 in) long, and 0.1 to 0.7 cm (0.039 to 0.276 in) wide. The small yellow flowers appear in summer, autumn and early winter (December to July), followed by small green fleshy fruit known as drupes. Within the genus Persoonia, it is a member of the Lanceolata group of 58 closely related species. P. linearis interbreeds with several other species where they grow together.

Found in dry sclerophyll forest on sandstone-based nutrient-deficient soils, P. linearis is adapted to a fire-prone environment; the plants resprout epicormic buds from beneath their thick bark after bushfires. The fruit are consumed by vertebrates such as kangaroo, possums and currawongs. As with other members of the genus, P. linearis is rare in cultivation as it is very hard to propagate by seed or by cuttings, but once propagated, it adapts readily, preferring acidic soils with good drainage and at least a partly sunny aspect.

Taxonomy

English botanist and artist Henry Cranke Andrews described Persoonia linearis in 1799, in the second volume of his Botanists Repository, Comprising Colour'd Engravings of New and Rare Plants.[2] He had been given a plant in flower by J. Robertson of Stockwell, who had grown it from seed in 1794.[3] The species name is the Latin linearis "linear", referring to the shape of the leaves.[4]

Meanwhile, German botanist Karl Friedrich von Gaertner had coined the name Pentadactylon angustifolium in 1807 from a specimen in the collection of Joseph Banks to describe what turned out to be the same species.[5] The genus name derived from the Greek penta- "five" and dactyl "fingers", and refers to the five-lobed cotyledons.[6] The horticulturist Joseph Knight described this species as the narrow-leaved persoonia (Persoonia angustifolia) in his controversial 1809 work On the cultivation of the plants belonging to the natural order of Proteeae,[7] but the binomial name is illegitimate as it postdated Andrews' description and name.[8] Carl Meissner described a population from the Tambo River in Victoria as a separate variety, Persoonia linearis var. latior in 1856,[9] but no varieties or subspecies are recognised.[2] German botanist Otto Kuntze proposed the binomial name Linkia linearis in 1891,[10] from Cavanilles' original description of the genus Linkia but the name was eventually rejected in favour of Persoonia.[6] In 1919, French botanist Michel Gandoger described three species all since reallocated to P. linearis; P. phyllostachys from material collected at Mount Wilson sent to him by the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney, and P. walteri and P. breviuscula from Melbourne-based plant collector Charles Walter, whose records have been questioned.[11] The short-leaved material of P. breviuscula was noted to have been collected in Queensland but this is now thought to have been incorrectly recorded.[12] Gandoger described 212 taxa of Australian plants, almost all of which turned out to be species already described.[11]

In 1870, George Bentham published the first infrageneric arrangement of Persoonia in Volume 5 of his landmark Flora Australiensis. He divided the genus into three sections, placing P. linearis in P. sect. Amblyanthera, and recognising Pentadactylon angustifolium as the same species, after examining the specimen in the Banksian Herbarium.[13] He described a variety sericea from the Shoalhaven River region and also noted the discrepancy in Robert Brown's description of the species. Brown had noted the bark to be smooth, in contrast to Ferdinand von Mueller and others who recorded the bark as layered.[13]

The genus was reviewed by Peter Weston for the Flora of Australia treatment in 1995, and P. linearis was placed in the Lanceolata group,[12] a group of 54 closely related species with similar flowers but very different foliage. These species will often interbreed with each other where two members of the group occur,[14] and hybrids with P. chamaepeuce, P. conjuncta, P. curvifolia, P. lanceolata, P. media, five subspecies of P. mollis, P. myrtilloides subsp. cunninghamii, P. oleoides, P. pinifolia and P. sericea have been recorded.[12] Robert Brown initially described the hybrid with P. levis as a species "Persoonia lucida",[4] which is now known as Persoonia × lucida,[15] and has been recorded from the southeast forests of the New South Wales south coast.[16]

Bentham wrote in 1870 that the name geebung, derived from the Dharug language word geebung or jibbong,[17][6] which had been used by the indigenous people for the fruits of this species.[13] It goes by the common names of narrow-leaved geebung or narrow-leaf geebung.[2] Naam-burra is an aboriginal name from the Illawarra region.[18]

Description

Persoonia linearis grows as a tall shrub to small tree, occasionally reaching 5 m (16 ft) in height but more commonly around 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) tall.[19] The flaky soft bark is dark grey on the surface,[12] while deeper layers are reddish. Within the bark are epicormic buds, which sprout new growth after bushfire.[14] The new growth is hairy. The leaves are more or less linear in shape, measuring 2 to 9 cm (0.79 to 3.54 in) in length and 0.1 to 0.7 cm (0.039 to 0.276 in) wide, with slightly down-rolled margins.[12]

The yellow flowers appear in summer, autumn and early winter (December to July),[19] peaking over January and February.[20] They are arranged in leafy racemes, and each stem may bear up to 50 flowers. P. linearis is described as auxotelic, which means each stalk bears an individual flower that is subtended by a leaf at its junction with the stem.[12] Known as pedicels, these are covered in fine hair and measure 2–8 mm in length.[12] Each individual flower consists of a cylindrical perianth, consisting of tepals fused for most of their length, within which are both male and female parts.[14] The tepals are 0.9–1.4 cm (0.35–0.55 in) long and covered in fine hair on the outside.[12] The central style is surrounded by the anther, which splits into four segments; these curl back and resemble a cross when viewed from above.[14] They provide a landing area for insects visiting the stigma, which is located at the tip of the style.[21] The flowers are followed by the development of smooth fleshy drupes, which are green and more or less round, measuring 1.3 cm (0.5 in) in diameter.[22] Mature drupes may have purple blotches.[4] Each bears one or two seeds within a woody "stone" and is shed once ripe, generally from September to November.[20]

Distribution and habitat

One of the most common geebungs,[4] Persoonia linearis is found from the Macleay River catchment on the New South Wales Mid North Coast to the Tambo River in eastern Victoria.[12] It is found from sea level to altitudes of 1,000 m (3,300 ft) with an average yearly rainfall of 700 to 1,400 mm (28 to 55 in).[20][23] It is a component of dry sclerophyll forest on both sandstone and clay soils.[4] It grows in sunny to lightly shaded areas in open forest or woodland with a shrubby understory. In the Sydney Basin, it is associated with such trees as Sydney peppermint (Eucalyptus piperita), silvertop ash (E. sieberi), blue-leaved stringybark (E. agglomerata), blackbutt (E. pilularis), grey ironbark (E. paniculata), snappy gum (E. rossii), Sydney blue gum (E. saligna), narrow-leaved stringybark (E. sparsifolia) and smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata) and shrubs such as Grevillea obtusiflora, G. phylicoides, Kowmung hakea (Hakea dohertyi), long leaf smoke bush (Conospermum longifolium) and stiff geebung (Persoonia rigida).[20] In the vicinity of Nowra and Jervis Bay, it is an understory component of the widespread Currambene Lowlands Forest community, alongside such plants as gorse bitter pea (Daviesia ulicifolia), bearded heath (Leucopogon juniperinus) and native daphne (Pittosporum undulatum) with spotted gum (Corymbia maculata), white stringybark (Eucalyptus globoidea) and woollybutt (E. longifolia) as the dominant trees. The tall dry sclerophyll forest is on hilly terrain with good drainage. The underlying soil is a yellow loam originating from mudstone, siltstone and sandstone.[24]

Ecology

Persoonia linearis is one of several species of Persoonia that regenerate by resprouting from trunks or stems greater than 2 cm (0.79 in) thick after bushfire,[20] an adaptation to the fire-prone habitat where it grows.[14] However, only larger trunks of 12–16 cm (4.7–6.3 in) diameter might survive to reshoot after very hot fires.[25] The thick papery bark shields and insulates the underlying epicormic buds from the flames.[14] The plant can reshoot from the base, but generally only if the stem or trunk is killed.[25]

Colletid bees of the genus Leioproctus, subgenus Cladocerapis exclusively forage on and pollinate flowers of many species of Persoonia. Bees of subgenus Filiglossa in the same genus, which also specialise in feeding on Persoonia flowers, do not appear to be effective pollinators.[14] Weighing 1900 mg (0.07 oz), the fruit are adapted to be eaten by vertebrates, such as kangaroos, possums and currawongs and other large birds.[20] Seeds have been recorded in the faeces of the brush-tailed rock-wallaby (Petrogale penicillata).[26]

Cultivation

Persoonia linearis is useful as a hedging plant and responds well to pruning.[22] Its foliage has been used in floral arrangements, and its colourful bark is a horticultural feature.[4] It is a fairly easy plant to grow in gardens, but is rarely seen due to difficulties in propagation.[4] Germination from seed is low, and can take many months.[21] Once established it can tolerate extended dry periods and is hardy to frosts.[22] Optimum growing conditions are part shade and a well-drained acid soil, though P. linearis grows readily in full sun.[22] Persoonias in general are sensitive to excessive phosphorus, and grow without fertiliser or with low-phosphorus slow-release formulations. They can also become deficient in iron and manganese.[27] First cultivated in England in 1794 from seed, it was also reportedly propagated from cuttings;[21] Andrews described it as a "handsome greenhouse plant, continuing to flower through the autumnal months and producing good seeds."[3] Joseph Knight reported that cuttings would be successful as long as material was "judiciously chosen", and that plants had set seed on occasion.[7]

A compound with antimicrobial activity was isolated from the ripening drupes of a hybrid of Persoonia linearis and P. pinifolia growing in the Australian National Botanic Gardens in 1994, and identified as 4-hydroxyphenyl 6-O-[(3R)-3,4-dihydroxy-2-methylenebutanoyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside.[28]

References

Citations

- ↑ Weston, P. (2020). "Persoonia linearis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T118153874A122769241. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T118153874A122769241.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/118153874/122769241. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Persoonia linearis Andrews". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni?taxon_id=60125.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Andrews, Henry C. (1799). Botanists Repository, Comprising Colour'd Engravings of New and Rare Plants. 2. London, United Kingdom: H.C. Andrews; T. Bensley. Plate 77. https://archive.org/stream/botanistsreposit12andr#page/n321/mode/2up.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Wrigley 1991, p. 489.

- ↑ "Pentadactylon angustifolium C.F.Gaertn.". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni?taxon_id=15727.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wrigley 1991, p. 475.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Knight, Joseph; [Salisbury, Richard] (1809). On the Cultivation of the Plants Belonging to the Natural Order of Proteeae. London, United Kingdom: W. Savage. pp. 99–100. https://books.google.com/books?id=dkUAAAAAQAAJ&q=Persoonia.

- ↑ "''Persoonia angustifolia'' Knight [nom. illeg. ]". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni?taxon_id=58148.

- ↑ Meissner, Carl (1856). Candolle, Alphonse de. ed. Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis. 14. Paris, France: Sumptibus Sociorum Treuttel et Würtz. p. 335. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/109211#page/341/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Linkia linearis (Andrews) Kuntze". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni?taxon_id=61337.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 McGillivray, Donald J. (1973). "Michel Gandoger's Names of Australian Plants". Contributions from the New South Wales National Herbarium 4 (6): 319–65. ISSN 0077-8753.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Weston, Peter H. (1995). "Persoonioideae". in McCarthy, Patrick. Flora of Australia: Volume 16: Eleagnaceae, Proteaceae 1. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-643-05693-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Bentham, George (1870). "Persoonia". Flora Australiensis. 5. London, United Kingdom: L. Reeve & Co. pp. 380–383, 397. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/26124296#page/394/mode/1up.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Weston, Peter H. (2003). "Proteaceae Subfamily Persoonioideae: Botany of the Geebungs, Snottygobbles and their Relatives". Australian Plants 22 (175): 62–78.

- ↑ "Persoonia x lucida R.Br.". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni?taxon_id=261668.

- ↑ Keith, David A.; Miles, Jackie; Mackenzie, Berin D. E. (1999). "Vascular flora of the South East Forests region, Eden, New South Wales". Cunninghamia 6 (1): 219–279. http://rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/58210/Cun6Kei210.pdf.

- ↑ Australian National Botanic Gardens (2007). "Aboriginal Plant Use – NSW Southern Tablelands: Geebung". Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment and Heritage. http://www.anbg.gov.au/apu/plants/persooni.html.

- ↑ Smith, Keith; Smith, Irene (1999). Grow Your Own Bushfoods. Kenthurst, New South Wales: New Holland Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 1-86436-459-9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Fairley, Alan; Moore, Philip (2000). Native Plants of the Sydney District: An Identification Guide (2nd ed.). Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-7318-1031-7.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Benson, Doug; McDougall, Lyn (2000). "Ecology of Sydney plant species: Part 7b Dicotyledon families Proteaceae to Rubiaceae". Cunninghamia 6 (4): 1017–1202 [1108]. https://www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/RoyalBotanicGarden/media/RBG/Science/Cunninghamia/Volume%206%20-%202000/Volume-6(4)-2000-Cun6Ben1016-1202.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Wrigley 1991, p. 476.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Elliot & Jones 1997, p. 221.

- ↑ Neave, Helen M.; Norton, Toyn W. (1998). "Biological Inventory for Conservation Evaluation: IV. Composition, Distribution and Spatial Prediction of Vegetation Assemblages in Southern Australia". Forest Ecology and Management 106 (2–3): 259–281. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00318-6.

- ↑ Keith, David A.; Simpson, Christopher; Tozer, Mark G.; Rodoreda, Suzette (2007). "Contemporary and Historical Descriptions of the Vegetation of Brundee and Saltwater Swamps on the Lower Shoalhaven River Floodplain, Southeastern Australia". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 128: 123–153.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Morrison, David A.; Renwick, John A. (2000). "Effects of Variation in Fire Intensity on Regeneration of Co-occurring Species of Small Trees in the Sydney Region". Australian Journal of Botany 48 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1071/BT98054.

- ↑ Short J. (1989). "The Diet of the Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby in New-South-Wales". Australian Wildlife Research 16 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1071/WR9890011.

- ↑ Elliot & Jones 1997, p. 206.

- ↑ MacLeod, John K.; Rasmussen, Hasse B.; Willis, Anthony C. (1997). "A New Glycoside Antimicrobial Agent from Persoonia linearis × pinifolia". Journal of Natural Products 60 (6): 620–622. doi:10.1021/np970006a. PMID 9296952.

Cited texts

- Elliot, Rodger W.; Jones, David L.; Blake, Trevor (1997). Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants Suitable for Cultivation: Volume 7 – N–Po. Port Melbourne: Lothian Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-85091-634-8.

- Wrigley, John; Fagg, Murray (1991). Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-17277-3.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q2072449 entry

|