Biology:Weygoldtina

| Weygoldtina | |

|---|---|

| |

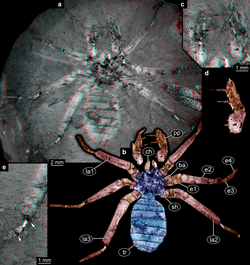

| Fossil specimen of W. anglica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Amblypygi |

| Family: | †Weygoldtinidae |

| Genus: | †Weygoldtina Dunlop, 2018 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

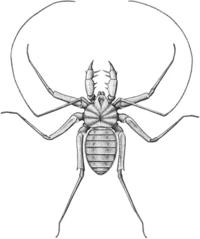

Weygoldtina is an extinct genus of tailless whip scorpion known from Carboniferous period, and the only known member of the family Weygoldtinidae.[1] It is known from two species described from North America and England and originally described in the genus Graeophonus,[2] which is now considered a nomen dubium.[1]

History

A single fossil from the Cape Breton Island was interpreted as a fossil dragonfly larva and described by Samuel Hubbard Scudder in 1876 as Libellula carbonaria.[3][4][1] The fossil was very incomplete, consisting of a solitary opisthosoma.[4] With the discovery of more complete fossils from Mazon Creek, Illinois, and Joggins, Nova Scotia, Samuel Scudder redescribed the fossils as amblypygids and moved the species to a new genus, Graeophonus as Graeophonus carbonarius. While describing the British species, Graeophonus anglicus, Reginald Innes Pocock noted significant differences between the Nova Scotian and more complete Mazon Creek fossils.[4] As a result he erected the species Graeophonus scudderi to accommodate the Mazon Creek specimen, and restricted species G. carbonarius to the Canadian specimens. It was later suggested by Reginald Pocock in 1913 that the two species, G. carbonarius and G. scudderi were indeed the same, and this has resulted in confusion over both the name to be used and number of species present in North America.[4] Graeophonus anglicus has been found in the English Middle Coal Measures of Coseley, Staffordshire. Known from ten specimens that are now deposited in the British Museum, the species was named by Reginald Pocock in 1911.[5]

However, in 2018, researchers considered that the genus Graeophonus is invalid, because the holotype specimen of G. carbonarius (=Libellula carbonaria) is poorly preserved and hard to identify as an amblypygid.[1] Even in 1911, Pocock considered that the holotype specimen possibly did not belong to an amplypygid.[5] More confusingly, A.I. Petrunkevitch suggested to use another more complete specimen as the holotype in 1913, even though the original holotype specimen was not lost at that time. To solve problems caused by this, Jason A. Dunlop erected a new genus, Weygoldtina, and placed most specimens of G. carbonarius and G. scudderi into Weygoldtina scudderi, and G. anglicus is renamed as Weygoldtina anglica.[1]

Morphology

W. scudderi had body length about 17 millimetres (0.67 in).[1]

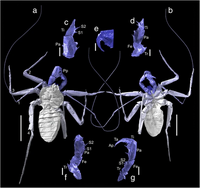

Body length of W. anglica ranges from 11–13 millimetres (0.43–0.51 in) for complete specimens, and the partly complete 18 millimetres (0.71 in) long specimen shows a distinct pear-shaped ocular tubercle on the carapace.[4] CT data confirmed the presence of lateral eye tubercles.[2] The center of the dorsal shield has a deep depression which probably acted as an attachment site for the muscles of the sucking stomach.[2] Raptorial pedipalps were not mantis-like shaped like most of modern amplypygid but similar to ones of modern genus Paracharon.[2] Main difference of pedipalp compared to Paracharon is the spine orientation. While the pedipalp spines in Paracharon appear to be almost parallel and slightly tilted outwards, W. anglica, however, the angle between the spines appears to be larger, at least 90 degrees. This character suggests that W. anglica used its pedipalps not exactly in the same way as the modern Paracharon.[6] Study in 2021 shows two prominent spines on each pedipalp, which were not recognized before.[6] Although first pairs of legs are not completely preserved, they are probably long and antenna-like, same as modern amblypygids.[2]

Main difference of two species is anterior projection from the prosomal dorsal shield. It is slightly wider, shorter and more diffuse in W. scudderi.[1]

Classification

The morphology of both the abdomen and pedipalps in Weygoldtina is very similar to the modern genus Paracharon. In 2007, Weygoldtina (Graeophonus at that time) was placed in Paracharontidae, same family as Paracharon. While Paracharon is notably blind, this is thought to be a secondary result of living almost exclusively within termite mounds. Thus the blindness was not considered a reason to exclude Graeophonus from Paracharontidae.[4] However, in 2017, Weygoldtina is rejected from Paracharontidae, and treated as stem-paleoamblypygid. Paleoamblypygi is a monophyletic suborder that contains Paracharon, Weygoldtina, in addition Paracharonopsis cambayensis that is described from Eocene Cambay amber.[2] In 2018, new family Weygoldtinidae is given for Weygoldtina.[1] Differences in morphology of pedipalps and first pair of leg in Paracharon and Weygoldtina may show closer relationship of Paracharon and Euamblypygi, but also this could be a point to an apomorphic condition of Weygoldtina. Researchers claimed that it needs to be considered that Weygoldtina is not as similar to Paracharon as a brief look might suggest, but is characterised by own specialisations.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Dunlop, Jason A. (2018-03-01). "Systematics of the Coal Measures whip spiders (Arachnida: Amblypygi)" (in en). Zoologischer Anzeiger. In honor of Peter Weygoldt 273: 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2017.11.004. ISSN 0044-5231. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044523117300967.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Knecht, Brian J.; Hegna, Thomas A. (2017). "The phylogeny of fossil whip spiders". BMC Evolutionary Biology 17 (1): 105. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0931-1. ISSN 1471-2148. PMID 28431496.

- ↑ Scudder, S.H. (1876). "A century of Orthoptera. Decade VI. Forficulariae (North America)". Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 18: 257–264.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Dunlop, J.A.; Zhou, G.R.S.; Braddy, S.J. (2007). "The affinities of the Carboniferous whip spider Graeophonus anglicus Pocock, 1911 (Arachnida:Amblypygi)". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 98 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1017/S1755691007006159. http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/18452/22508.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Petrunkevitch, Alexander (1913) (in en). A Monograph of the Terrestrial Palaeozoic Arachnida of North America. Yale University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=U64LAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Haug, Carolin; Haug, Joachim T. (2021-09-01). "The fossil record of whip spiders: the past of Amblypygi" (in en). PalZ 95 (3): 387–412. doi:10.1007/s12542-021-00552-z. ISSN 1867-6812.

Further reading

- Dunlop, J.A. (1994). An Upper Carboniferous amblypygid from the Writhlington Geological Nature Reserve. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 105:245-250.

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|