Biology:Red-naped ibis

| Red-naped ibis | |

|---|---|

| |

| A pair | |

| Scientific classification Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Threskiornithidae |

| Genus: | Pseudibis |

| Species: | P. papillosa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudibis papillosa (Temminck, 1824)

| |

| |

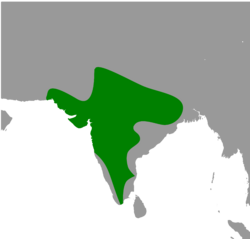

| Approximate distribution range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Inocotis papillosus[2] | |

The red-naped ibis (Pseudibis papillosa) also known as the Indian black ibis or black ibis is a species of ibis found in the plains of the Indian Subcontinent. Unlike other ibises in the region it is not very dependent on water and is often found in dry fields a good distance away from water. It is usually seen in loose groups and can be told by the nearly all dark body with a white patch on the shoulder and a bare dark head with a patch of crimson red warty skin on the crown and nape. It has a loud call and is noisy when breeding. It builds its nest most often on the top of a large tree or palm.

Description

The red-naped ibis is a large black bird with long legs and a long downcurved bill. The wing feathers and tail are black with blue-green gloss while the neck and body are brown and without gloss. A white patch on the shoulders stands out and the top of the featherless head is a patch of bright red warty skin. The warty patch, technically a caruncle,[3] is a triangular patch with the apex at the crown and the base of the triangle behind the nape that develops in adult birds. The iris is orange red. Both sexes are identical and young birds are browner and initially lack the bare head and crown. The bills and legs are grey but turn reddish[4] during the breeding season.[5][6] The toes have a fringing membrane and are slightly webbed at the base.[7]

They are usually silent but call at dawn and dusk and more often when nesting. The calls are a series of loud braying, squealing screams that descend in loudness.[8]

This species can be confused with the glossy ibis when seen at a distance but the glossy ibis is smaller, more gregarious, associated with wetlands and lacks the white on the wing and has a fully feathered head.[7]

Taxonomy

The species was first given its scientific name by Temminck in 1824. He placed it in the genus Ibis but it was separated into the genus Inocotis created by Reichenbach and this was followed by several major works including the Fauna of British India although the genus Pseudibis in which Hodgson had placed the species had precedence based on the principle of priority.[9] The red-naped ibis (P. papillosa) included the white-shouldered ibis as P. papillosa davisoni, a subspecies, from 1970 but these are now treated as distinct species, although closely related.[10] The main morphological difference between the two species is seen in the crown and the upper neck. While P. papillosa has a patch of red tubercles on the back of the crown, P. davisoni lacks it. Also, adult P. papillosa have a narrow, bright red mid-crown that becomes broader on the hindcrown, whereas, adult P. davisoni has a bare pale blue middle hindcrown that extends to the upper hindneck and forms a complete collar around the upper neck.[11]

| Measurements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| India[5] | |||

| Template:Infobox bird/population |

Distribution and habitat

The red-naped ibis is widely distributed in the plains of the Indian Subcontinent. The habitats this bird is found at is lakes, marshes, riverbeds and on irrigated farmlands. It is gregarious and generally forages on margins of wetlands in small numbers. It is a common breeding resident in Haryana and Punjab and the Gangetic plain. It extends into southern India but is not found in the forested regions or the arid zone of the extreme southeast of the peninsula or Sri Lanka.[5]

The red-naped ibis is diurnal in its foraging and other activities,[12] at night roosting communally on trees or on islands.[13]

Food and foraging

The red-naped ibis is omnivorous, feeding on carrion,[14] insects, frogs, and other small vertebrates as well as grain.[5] They forage mainly in dry open land and stubbly fields, sometimes joining egrets and other birds on land being tilled to feed on disturbed insects and exposed beetle grub. They walk and like other tactile-feeding ibises, probe in the soft ground. The rarely wade in water[6] but have been observed seeking out frogs hiding in crab holes.[15] They sometimes feed at garbage dumps.[8] During droughts they are known to feed on carrion and insect larvae feeding on meat. They also feed on groundnut and other crops. In British India, indigo planters considered them useful as they appeared to consume a large number of crickets in the fields.[16][17]

Ibises roost in groups and fly to and from the regularly used roost site in "V" formation.[7]

Breeding

Red-naped ibises usually nest individually and not in mixed species heronries. They very rarely form small colonies consisting of 3-5 pairs in the same tree. The breeding season is variable but most often between March and October and tending to precede the monsoons. When pair-bonding, females beg for food from the males at foraging grounds. Males also trumpet from the nest site.[13] The nests are mainly large stick platforms that are 35-60 centimetres in diameter and about 10-15 centimetres deep. Old nests are reused as are those of kites and vultures. The nests are loosely lined with straw and fresh material to the nest is added even when the eggs are being incubated. The nests are usually at a height of 6–12 metres above ground, on banyan (Ficus benghalensis) or peepal (Ficus religiosa) trees, often close to human habitation. In recent times they have also taken to nesting on powerline pylons in Gujarat.[18] Pairs copulate mainly when perched on trees.[13] The eggs are 2–4 in number and pale bluish green in colour. They are sparsely flecked and have pale reddish blotches. Both male and female red-naped ibis incubate the eggs which hatch after 33 days.[5][19][20]

Parasites

The nematode Belanisakis ibidis has been identified from the small intestines of the species[21] while the feathers of ibises are host to specific species of bird lice in the genus Ibidoecus. The species found in the red-naped ibis is Ibdidoecus dennelli.[22] Patagifer chandrapuri, a species of Digenea flatworm has been found in the intestines of specimens from Allahabad.[23] In captivity, a trematode Diplostomum ardeiformium has been described from a red-naped ibis host.[24] Protist parasites include Eimeria-like organisms.[25]

In culture

The Tamil Sangam literature mentions a bird called the "anril" which was described as having a curved bill and calling from atop palmyra palms (Borassus flabellifer). Madhaviah Krishnan identified the bird positively as the black ibis and ruled out contemporary suggestions that this was a sarus crane. He based his identification on a line that mentions the arrival of anrils at dusk and calling from atop palmyra palms. He also pointed out ibises to locals and asked them for the name and noted that a few did refer to it as anrils. Sangam poetry also mentions that the birds mated for life and always walked about in pairs, one of the leading reasons for others to assume that this was the sarus crane, a species that is not found in southern India.[26][27]

A number of names in Sanskrit literature including "kālakaṇṭak" have been identified as referring to this species.[28] Jerdon noted the local names of "karankal" and "nella kankanam" in Telugu and "buza" or "kālā buza" in Hindi.[29]

In British India, sportsmen referred to the species as the "king curlew",[30] "king ibis" or "black curlew"[31] and it was considered good eating as well as sport for falconers (using the Shaheen falcon).[29] They would race and soar to escape falcons.[32]

Status and conservation

The species has declined greatly in Pakistan due to hunting and habitat loss. The species has been largely unaffected in India and they are traditionally tolerated by farmers.[4]

The species is considered to be secure in the wild but a few zoos including the ones at Frankfurt, Singapore (Jurong park) have successfully bred the species in captivity. An individual lived in captivity at Berlin zoo for 30 years.[33]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2016). "Pseudibis papillosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22697528A93619283. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22697528A93619283.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22697528/93619283. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Blandford, W.T. (1898). The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 4. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 362–363. https://archive.org/stream/birdsindia04oaterich#page/362/mode/2up.

- ↑ Stettenheim, Peter R. (2000). "The integumentary morphology of modern birds- an overview". American Zoologist 40 (4): 461–477. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.461.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hancock, James; Kushlan, James A.; Kahl, M. Philip (2010). Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. A&C Black. pp. 241–244.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Ali, Salim; Ripley, S. Dillon (1978). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 112–113.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Baker, E.C. Stuart (1929). The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 6 (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 316–317. https://archive.org/stream/BakerFbiBirds6/BakerFBI6#page/n355/mode/2up.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds (4th ed.). London: Gurney and Jackson. pp. 497–498. https://archive.org/stream/popularhandbooko033226mbp#page/n545/mode/2up.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rasmussen, P.C.; J.C. Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington, D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Oberholser, Harry C. (1922). "Inocotis Reichenbach to be replaced by Pseudibis Hodgson". Proceedings of Biology ([Washington, Biological Society of Washington]) 35: 79. https://archive.org/stream/proceedingsofbio35biol#page/78/mode/1up.

- ↑ Holyoak, David (1970). "Comments on the classification of the Old World Ibises". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 90 (3): 67–73. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinofbritis8990brit#page/66/mode/1up.

- ↑ Collar J, Nigel; Eames C, Jonathan (2008). "Head and sex-size dimorphism in Pseudibis papillosa and P.davisoni". BirdingASIA 10: 36. http://people.ds.cam.ac.uk/cns26/njc/Papers/Pseudibis.pdf.

- ↑ "Indian black ibis / Oriental black ibis / Red napped ibis (Pseudibis papillosa Temminck)". http://www.ibisring.org/article/indian-black-ibis.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Hancock, James A.; Kushlan, James A.; Kahl, M.Philip (1992). Storks, ibises and spoonbills of the world. Academic Press. pp. 241–244.

- ↑ Khan, Asif N. (2015-04-01). "Indian Black Ibis Pseudibis papillosa feeding on carrion" (in en). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 112 (1): 28. doi:10.17087/jbnhs/2015/v112i1/92323. ISSN 0006-6982.

- ↑ Johnson, J. Mangalraj (2003). "Black ibis Pseudibis papillosa feeding on frogs from crab holes". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 100 (1): 111–112. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48602685.

- ↑ Inglis, C.M. (1903). "The birds of the Madhubani sub-division of the Darbhanga district, Tirhut, with notes on species noticed elsewhere in the district. Part 6". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 15 (1): 70–77. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2096481.

- ↑ Mason, C.W. (1911). Maxwell-Lefroy, H.. ed. The food of birds in India.. Imperial Department of Agriculture in India. pp. 280–280–282. https://archive.org/stream/foodofbirdsinind00masorich#page/280/mode/2up/.

- ↑ Ali, A.H.M.S.; Kumar, Ramesh; Arun, P.R. (2013). "Black ibis Pseudibis papillosa nesting on power transmission line pylons, Gujarat, India". BirdingAsia 19: 104–106.

- ↑ Salimkumar, C.; Soni, V.C. (1984). "Laboratory observations on the incubation period of the Indian Black Ibis Pseudibis papillosa (Temminck)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 81 (1): 189–191. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48874097.

- ↑ Hume, A.O. (1890). The nest and eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 3. (2nd ed.). London: R.H. Porter. pp. 228–231. https://archive.org/stream/nestseggsofindia03humerich#page/228/mode/2up/.

- ↑ Inglis, William G. (1954). "On some nematodes from Indian vertebrates. I. Birds". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 12 7 (83): 821–826. doi:10.1080/00222935408651795.

- ↑ Tandan, B.K. (1958). "Mallophagan parasites from Indian birds-Part V. Species belonging to the genus Ibidoecus Cummings, 1916 (Ischnocera)". Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 110 (14): 393–410. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1958.tb00379.x. http://darwin.biology.utah.edu/PubsHTML/LicePubPages/LicePDF's/1958/Tandan1958.pdf.

- ↑ Faltynkova, Anna; Gibson, David I.; Kostadinova, Aneta (2008). "A revision of Patagifer Dietz, 1909 (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) and a key to its species". Systematic Parasitology 70 (3): 159–183. doi:10.1007/s11230-008-9136-8. PMID 18535788.

- ↑ Odening, Klaus (1962). "Trematoden aus indischen Vögeln des Berliner Tierparks" (in de). Zeitschrift für Parasitenkunde 21 (5): 381–425. doi:10.1007/BF00260995.

- ↑ Chauhan P. P. S, Bhatia B. B. (1970). "Eimerian oozysts from Pseudibis papillosa". Indian Journal of Microbiology 10 (2): 53–54.

- ↑ Krishnan, M. (1986) The Anril. Reprinted without source details in Nature's Spokesman (2000) edited by Ramachandra Guha. Oxford University Press. pp. 93-95.

- ↑ Varadarajan, Munuswamy (1957). The Treatment of Nature in Sangam Literature. Tirunelveli: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society. p. 260. https://archive.org/stream/TreatmentNatureInSangamLiterature/Treatment%20nature%20in%20Sangam%20literature#page/n281/mode/2up.

- ↑ Dave, K.N. (1985). Birds in Sanskrit literature. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 384.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 The birds of India. Volume 3. Calcutta: George Wyman and Co.. 1864. pp. 769–770. https://archive.org/stream/birdsofindiabein03jerd#page/768/mode/2up.

- ↑ Le Messurier, A. (1904). Game, Shore, and Water Birds of India. (4th ed.). London: W. Thacker and Co.. pp. 183–184. https://archive.org/stream/gamesshoreandwat029723mbp#page/n191/mode/2up/.

- ↑ Dewar, Douglas (1920). Indian Birds being a key to the common birds of the plains of India.. London: John Lane. pp. 217. https://archive.org/stream/indianbirdsbeing00dewa#page/217/mode/1up/.

- ↑ Burton, Richard F. (1852). Falconry in the valley of the Indus. London: John Van Voorst. pp. 57–58. https://archive.org/stream/falconryinvalle01burtgoog#page/n83/mode/2up/s.

- ↑ Brouwer, Koen; Schifter, Herbert; Jones, Marvin L. (1994). "Longevity and breeding records of ibises and spoonbills in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook 33: 94–102. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1994.tb03561.x.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q845946 entry

|