Biology:Salmon shark

| Salmon shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Lamnidae |

| Genus: | Lamna |

| Species: | L. ditropis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lamna ditropis C. L. Hubbs & Follett, 1947

| |

| |

| Range of the salmon shark | |

The salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) is a species of mackerel shark found in the northern Pacific ocean. As an apex predator, the salmon shark feeds on salmon, squid, sablefish, and herring.[2] It is known for its ability to maintain stomach temperature (homeothermy),[3] which is unusual among fish. This shark has not been demonstrated to maintain a constant body temperature. It is also known for an unexplained variability in the sex ratio between eastern and western populations in the northern Pacific.[4]

Description

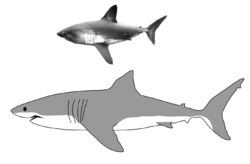

Adult salmon sharks are medium grey to black over most of the body, with a white underside with darker blotches. Juveniles are similar in appearance, but generally lack blotches. The snout is short and cone-shaped, and the overall appearance is similar to a small great white shark. The eyes are positioned well forward, enabling binocular vision to accurately locate prey.[5]

The salmon shark generally grows to between 200 and 260 cm (6.6–8.6 ft) in length and weighs up to 220 kg (485 lb).[6] Males appear to reach a maximum size slightly smaller than females. Unconfirmed reports exist of salmon sharks reaching as much as 4.3 m (14.2 ft); however, the largest confirmed reports indicate a maximum total length of about 3.0 m (10 ft).[4] The claims of maximum reported weight over 450 kg (992 lb) are "unsubstantiated".[4][6]

Biology

Reproduction

The salmon shark is ovoviviparous, with a litter size of two to six pups.[7] As with other Lamniformes shark species, the salmon shark is oophagous, with embryos feeding on the ova produced by the mother.

Females reach sexual maturity at eight to ten years, while males generally mature by age five.[8] Reproduction timing is not well understood, but is believed to be on a two-year cycle with mating occurring in the late summer or early autumn.[4] Gestation is around nine months. Some reports indicate the sex ratio at birth may be 2.2 males per female, but the prevalence of this is not known.[4]

Homeothermy

As with only a few other species of fish, salmon sharks have the ability to regulate their body temperature.[3] This is accomplished by vascular counter-current heat exchangers, known as retia mirabilia, Latin for "wonderful nets". Arteries and veins are in extremely close proximity to each other, resulting in heat exchange. Cold blood coming from the gills to the body is warmed by blood coming from the body. This results in blood coming from the body losing its heat so that by the time it interacts with cold water from the gills, it is about the same temperature, so no heat is lost from the body to the water. Blood coming towards the body regains its heat, allowing the shark to maintain its body temperature. This minimizes heat lost to the environment, allowing salmon sharks to thrive in cold waters.

Their homeothermy may also rely on SERCA2 and ryanodine receptor 2 protein expression, which may have a cardioprotective effect.[9]

Range and distribution

It is common in continental offshore waters, but ranges from inshore to just off beaches. It occurs singly, in feeding aggregations of several individuals, or in schools. Tagging has revealed a range which includes sub-Arctic to subtropical waters.[9]

The salmon shark occurs in the North Pacific Ocean, in both coastal waters and the open ocean. It is believed to range as far south as the Sea of Japan and as far north as 65°N in Alaska and in particular in Prince William Sound during the annual salmon run. Individuals have been observed diving as deep as 668 m (2,192 ft),[10] but they are believed to spend most of their time in epipelagic waters.

Regional differences

Age and sex composition differences have been observed between populations in the eastern and western North Pacific. Eastern populations are dominated by females, while the western populations are predominantly male.[6] Whether these distinctions stem from genetically distinct stocks, or if the segregation occurs as part of their growth and development, is not known. The population differences may be a result of Japanese fishermen harvesting the male population. Japanese herbalists use the fins of males as ingredients in many traditional medicines said to treat various forms of cancer.[11]

Human interactions

Currently, no commercial fishery for salmon shark exists, but they are occasionally caught as bycatch in commercial salmon gillnet fisheries, where they are usually discarded. Commercial fisheries regard salmon sharks as nuisances since they can damage fishing gear[7] and consume portions of the commercial catch. Fishermen deliberately injuring salmon sharks have been reported.[12]

Sport fishermen fish for salmon sharks in Alaska.[13] Alaskan fishing regulations limit the catch of salmon sharks to two per person per year. Sport fishermen are allowed one salmon shark per day from April 1 and ending the following March 31 in British Columbia.[14]

The flesh of the fish is used for human consumption, and in the Japanese city of Kesennuma, Miyagi, the heart is considered a delicacy for use in sashimi.[7]

Although salmon sharks are thought to be capable of injuring humans, few, if any, attacks on humans have been reported, but reports of divers encountering salmon sharks and salmon sharks bumping fishing vessels have been given.[12] These reports, however, may need positive identification of the shark species involved.

Declines in the abundance of economically important Chinook salmon in the 2000s may be attributed to increased predation by salmon sharks, based on remote temperature readings from tagged salmon that indicate they have been swallowed by sharks.[15]

See also

- List of sharks

References

- ↑ Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W. et al. (2019). "Lamna ditropis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39342A124402990. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T39342A124402990.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/39342/124402990. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Hulbert, Leland B.; Rice, J. Stanley (December 2002). "Salmon Shark, Lamna ditropis, Movements, Diet and Abundance in the Eastern North Pacific Ocean and Prince William Sound, Alaska".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Goldman, Kenneth; Anderson, Scot; Latour, Robert; Musick, John A. (2004). "Homeothermy in adult salmon sharks, Lamna ditropis". Environmental Biology of Fishes 71 (4): 403–411. doi:10.1007/s10641-004-6588-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Goldman, Kenneth (August 2002). Aspects of Age, Growth, Demographics, and Thermal Biology of Two Lamniform Shark Species. PhD Dissertation, College of William and Mary, School of Marine Science.

- ↑ "Salmon shark". https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/species/lamna-ditropis#desc-range.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Goldman, Kenneth; Musick, John A. (2006). "Growth and maturity of salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) in the eastern and western North Pacific, and comments on back-calculation methods". Fishery Bulletin 104 (2): 278–292.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Compagno, Leonard (2001). Sharks of the World, Vol. 2. Rome, Italy: FAO. http://www.fao.org/fi/eims_search/advanced_s_result.asp?JOB_NO=x9293.

- ↑ Nagasawa, Kazuya (1998). "Predation by Salmon Sharks (Lamna distropis) on Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) in the North Pacific Ocean". Bulletin of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission 1: 419–432.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Weng, Kevin C.; Pedro C. Castilho; Jeffery M. Morrissette; Ana M. Landeira-Fernandez; David B. Holts; Robert J. Schallert; Kenneth J. Goldman; Barbara A. Block (2005). "Satellite Tagging and Cardiac Physiology Reveal Niche Expansion in Salmon Sharks". Science 310 (5745): 104–106. doi:10.1126/science.1114616. PMID 16210538. Bibcode: 2005Sci...310..104W. http://www.tunaresearch.org/reprints/weng2005.pdf.

- ↑ Hulbert, Leland B.; Aires-da-Silva, Alexandre M.; Gallucci, Vincent F.; Rice, J. Stanley (2005). "Seasonal foarging movements and migratory patterns of female Lamna ditropis tagged in Prince William Sound, Alaska". Journal of Fish Biology 67 (2): 490–509. doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2005.00757.x.

- ↑ "Traditional medicines continue to thrive globally - CNN.com". http://edition.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/06/24/traditional.treatment/index.html?iref=24hours.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Biology of the Salmon Shark". Reefquest Center for Shark Research. http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/shark_profiles/l_ditropis.htm.

- ↑ "Fishing for Salmon Shark in Alaska". Fish Alaska Magazine. http://www.fishalaskamagazine.com/fish/salmon_shark.htm.

- ↑ "Refresh". http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/rec/species-especes/fintable-tableaupoisson-eng.html.

- ↑ Jim Paulin (17 July 2016). "Salmon sharks might play a role in king salmon declines". Anchorage Daily News. https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/science/2016/07/17/salmon-sharks-might-play-a-role-in-king-salmon-declines/.

External links

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "Lamna ditropis" in FishBase. May 2006 version.

- Salmon shark fact sheet

- TOPP, Tagging of Pacific Predators, a research group that tags salmon sharks to learn more about their habits.

- IMDB entry for Icy Killers, a wild-life documentary about salmon sharks.

Wikidata ☰ Q74371 entry

|