Biology:Rhizodontida

| Rhizodontida | |

|---|---|

| |

| A fossil of Sauripterus taylori | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Sarcopterygii |

| Clade: | Tetrapodomorpha |

| Class: | †Rhizodontida |

| Order: | †Rhizodontiformes Andrews & Westoll, 1970 |

| Genera | |

| |

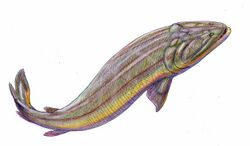

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs[3] known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian - the earliest known species is about 377 million years ago (Mya), the latest around 310 Mya. Rhizodonts lived in tropical rivers and freshwater lakes and were the dominant predators of their age. They reached huge sizes - the largest known species, Rhizodus hibberti from Europe and North America, was an estimated 7 m in length, making it the largest freshwater fish known.

Description

The upper jaw had a marginal row of small teeth on the maxilla and premaxilla, medium-sized fangs on the ectopterygoid and dermopalatine bones, and large tusks on the vomers and premaxillae. On the lower jaw were marginal teeth on the dentary, with fangs on the three coronoids and a huge tusk at the symphysial tip of the dentary. Apparently, the left and right mandibles rotated inwards towards each other on biting. This may have been a kinetic mechanism to dig the marginal teeth more deeply into the prey, to help grip slippery or struggling items.

The trunk was elongated, with pelvic, two dorsal and anal fins much reduced and placed posteriorly The anal and second dorsal fins formed a functional part of the tail. The lateral line system was elaborated on the skull and pectoral girdle - in Strepsodus the main trunk lateral line also had several subsidiary lines running parallel to it. This probably helped rhizodonts detect prey in the turbid, swampy environments where they lived.

Rhizodont pelvic fins are known only from external morphology. They are smaller than the pectoral fins and positioned toward the rear of the body. In comparison to the other fins, the pectoral fins were much enlarged. They had a well-developed internal skeleton surrounded by robust, largely unsegmented lepidotrichia; the whole fin was then covered in deeply overlapping scales. This turned the pectoral fin into a broad paddle.

Phylogeny

The cladogram presented below is based on a 2021 study by Clement and colleagues:[4]

| Rhizodontida |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ecology

Judging from their anatomy, rhizodonts had an extremely powerful bite. They probably employed a 'grip and drag' hunting technique, where prey was ambushed, the tusks sunk in to secure it, and then depending on its size, either thrashed on the surface to subdue it, or dragged to where the rhizodont could consume it without being disturbed. Their prey probably included large sharks, lungfish, and other lobe-finned fishes, and even tetrapods, because all tetrapods at this time still had to lay their eggs in water.

References

- ↑ Johanson, Z.; Jeffery, J.; Challands, T.; E. Pierce, S.; Clack, J. A. (2020). "A New Look at Carboniferous Rhizodontid Humeri (Sarcopterygii; Tetrapodomorpha)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40 (3): e1813150. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1813150. Bibcode: 2020JVPal..40E3150J. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/13147939.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Coates, M. I.; Friedman, M. (2010). "Litoptychus bryanti and characteristics of stem tetrapod neurocrania". Morphology, Phylogeny and Paleobiogeography of Fossil Fishes: 389–416. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/213770196.

- ↑ Clack, Jennifer A. (2012). Gaining Ground: The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods. Indiana University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-253-35675-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6Ztrhm8uLQ0C&pg=PA75. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Clement, A. M.; Cloutier, R.; Lu, J.; Perilli, E.; Maksimenko, A.; Long, J. (10 December 2021). "A fresh look at Cladarosymblema narrienense, a tetrapodomorph fish (Sarcopterygii: Megalichthyidae) from the Carboniferous of Australia, illuminated via X-ray tomography". PeerJ 9: e12597. doi:10.7717/peerj.12597. PMID 34966593.

- Johanson, Z. & Ahlberg, P.E. (1998) A complete primitive rhizodont from Australia. Nature 394: 569–573.

- Johanson, Z., and Ahlberg, P. E. (2001) Devonian rhizodontids and tristichopterids (Sarcopterygii; Tetrapodomorpha) from East Gondwana. Trans. R. Soc. Earth Sci. 92: 43–74.

Classification after Benton, M.J. (2005) Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN:0-632-05637-1. ISBN:978-0-632-05637-8.

External links

- http://www.palaeos.com/Vertebrates/Units/140Sarcopterygii/140.700.html#Rhizodontiformes

- https://web.archive.org/web/20121212033229/http://www.donnasaxby.com/rhizodonts/

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|