Biology:Kentish plover

| Kentish plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in breeding plumage, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: | C. alexandrinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius alexandrinus | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Range of Ch. alexandrinus Breeding Resident Non-breeding Vagrant (seasonality uncertain)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

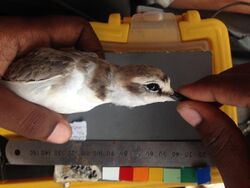

The Kentish plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) is a small cosmopolitan shorebird (40-44 g) of the family Charadriidae that breeds on the shores of saline lakes, lagoons, and coasts, populating sand dunes, marshes, semi-arid desert, and tundra.[1][2] Both male and female birds have pale plumages with a white underside, grey/brown back, dark legs and a dark bill; however, additionally the male birds also exhibit very dark incomplete breast bands, and dark markings either side of their head, therefore the Kentish plover is regarded as sexually dimorphic[3]

Charadrius alexandrinus has a large geographical distribution, ranging from latitudes of 10º to 55º, occupying North Africa, both mainland, such as Senegal, and island, such as the Cape Verde archipelago, Central Asia, for example alkaline lakes in China , and Europe, including small populations in Spain and Austria. Some populations are migratory and often winter in Africa, whereas other populations, such as various island populations, do not migrate.[4][5] Its common English name comes from the county of Kent, where it was once found, but it has not bred in Britain since 1979.[6]

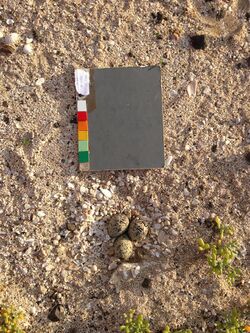

Kentish plovers are ground-nesting birds, often with a preference for low, open, moist nesting sites away from thick vegetation and human activity. They use a number of materials to build their nests, mainly consisting of shells, pebbles, grass and leaves in a small scrape in the ground.[7][8] Like most plovers, the Kentish plovers are predominantly insectivores, feeding on a large range of arthropods and invertebrates depending on the environment, by using a run and stop method.[9][10]

Taxonomy

The Kentish plover is in a state of taxonomic flux.

Until 2009, the Kentish plover species was universally thought to include the North American snowy plover species, however a novel genetic research paper suggested that they were in fact separate species.[11] In July 2011, the International Ornithological Congress (IOC), and the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) pronounced the snowy plover as a separate species Charadrius nivosus.

The white-faced plover (Charadrius dealbatus) was also split and a paper was published about a possible split from the Kentish plover, the Hanuman plover.

Hanuman plover

The subspecies Charadrius alexandrinus seebohmi was recently split as the Hanuman Plover, in 2023.[12] The discoverers stated in a webinar that the scientific name will likely not be Charadrius seebohmi. It was named after the chain of islands along the Palk Strait, said to be built by Hanuman, the monkey god in Hinduism.[13]

Description

The Kentish plover is a small shorebird weighing around 40 g as an adult. Both male and female birds have black bills and dark legs, however adults have dimorphic plumage. During the breeding season, males have a black horizontal head bar, two incomplete dark breast-bands on each side of their breast, black ear coverts and a rufous nape and crown (although there is some variation between breeding populations), whereas the females are paler in these areas, without the dark markings.[14][15] In the early breeding season, it is easy to distinguish between males and females since the ornaments are very pronounced, but as the breeding season progresses, the differences between the two sexes decrease. Moreover, males have longer tarsi and longer flank feathers than females.[15][16] Longer flank feathers are thought to be an advantage for incubation and brood care, as the quality of feathers is associated with heat insulation.[17] There are multiple significant predictors of plumage ornamentation in Kentish plovers. Firstly, the interaction between the advancement of the breeding season and rainfall seem to affect ornamentation. Male ornaments become more elaborated over the course of a breeding season in regions with high rainfall, whereas in regions with low rainfall, male ornaments become lighter. Secondly, the interaction between the breeding system and the sex can predict the degree of plumage ornamentation. In polygamous populations, the sexual ornaments are more pronounced, generating a stronger sexual dimorphism than in monogamous populations. The difference is especially witnessed in males, whereby the ornaments are darker and smaller in polygamous populations compared to monogamous populations, where males have lighter and larger ornaments. This is thought to be the result of a trade-off between the size and intensity of the ornaments.[14][18]

Distribution, movement, and habitats

Distribution

Kentish plovers have an extremely wide geographical distribution and their habitats vary not just spatially but environmentally too. They are known to reside and breed in multiple types of habitat, from desert with ground temperatures reaching 50 °C to tundra. The distribution of this species’ breeding areas covers Europe, Asia and Africa,[4][19]). In Europe, populations are typically found in the west; although there was once a breeding population in Hungary, Kentish plovers no longer breed there. In Africa, populations are found on the southern coast of Senegal and along the Northern coast of the Mediterranean, and the Red Sea coast. The breeding area continues along the Arabian Peninsula, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Bahrain in the Middle East. Small populations can be found on islands too, such as the Cape Verde archipelago, the Canary Islands, and the Azores. It is a rare vagrant in Australia .[20][21] Some populations do not migrate, such as the Maio (Cape Verde) population, however other populations can migrate reasonable distances, for example, plovers that spend winter in North Africa have been known to migrate to Turkey and Greece in the spring. Some birds breeding in western Europe are not known to travel very far, just within Europe, however some do travel, mainly to Western Africa.[22]

Habitats and movement

The breeding habitats are most commonly alkali lake shores, wetlands, salt marshes, and coastland, which is fitting with the results of a study that investigated what makes an environment suitable for a breeding habitat for the Kentish plover. By analysing four variables of all known nests, the study found that plovers prefer to nest in areas of low elevation, low vegetation, high moisture and places faraway from human activity and settlements,.[7][19]

There have been observations of parents moving their chicks from poor food areas to better food areas, with chicks subsequently growing stronger in the high food areas. This suggests that parents strategically move their chicks and change habitats. Moving young has benefits: protection from predators, obtaining more food, avoiding competition for food and space, avoiding potential infanticide due to competition, and avoiding territory defences from others. However, this is a trade-off as there are also costs to moving young: moving expends a lot of energy, especially in young, therefore chick growth may be stunted as energy is used on movement rather than growth, the chance of mortality due to starvation or predation increases whilst moving through open areas and the area of high food may have a lot of predators in it already. Overall, chick growth and brood survival benefit from moving to a higher food area, therefore increasing reproductive success of parents, hence why the parents move their chicks. The study also found that the larger and heavier females were more likely to move chicks, perhaps because they could defend their chicks from neighbouring parents [23]

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

The Kentish plover has an especially flexible breeding system, including both monogamous and polygamous behaviours within populations. It is known that breeding pairs return to breed with each other the following year, however mate changes have also been observed both between and within breeding seasons.[24][25]

Along with mate changes, EPF's (extra pair fertilisations) are also witnessed in some populations, by females copulating with extra-pair males (EPP- extra pair paternity), or males copulating with extra pair females, who then lay their eggs in the male's nest (QP- quasi-parasitism). A theory as to why such EPC's occur is that this mechanism evolved to avoid the deleterious effects of inbreeding. This is supported by a study by Blomqvist et al.,[26] showing that EPC's are more common when a breeding pair are more closely related to each other. Another theory is that females may seek out EPC's with high quality males to get the ‘good genes’ for their sons, following the ‘sexy sons’ hypothesis. The breeding season of Kentish plovers lasts on average between 2 and 5 months and varies in the time of year dependent on the particular population. Breeding pairs can replace failed clutches more than once per breeding season, with the same or a different mate, and both males and females can parent more than one brood, due to mate change and EPC's as mentioned above.[1] The courtship displays also vary between populations of plovers, especially between socially monogamous and polygamous populations, for example in polygamous populations the time spent courting is significantly higher for both males and females than in monogamous populations. Courtship displays include active gestures such as flat running, building nest scrapes (small shallow cavities in the ground that are later built into nests), and fighting/running to defend a breeding territory (mainly by males) [27]

Territories

Kentish plovers inhabit sandy areas or salt-marshes in close proximity to water. Inland populations can be found near alkaline or saline lakes, ponds or reservoirs. The populations inhabiting the coastal regions can be found in semi-desert habitats i.e. on barren beaches, near lagoons and sand extractions on beaches or dunes.

Kentish plovers are territorial shorebirds; the male usually has a territory and attracts females with courtship displays. The parents are actively defending their nest territories from predators by chasing, fighting or posturing them. When approached by predators in close proximity to the nest, the Kentish plovers quickly run away from the nest and start doing distraction displays to focus the predator's attention on themselves and lure them away from the nest. These displays include calling or crawling on the ground flapping their wings. Males tend to be more aggressive than females, but females performing riskier defensive behaviors than males.[28] When a plover's territory has been invaded, it invades a neighboring family's territory. This is when fights between males frequently occur because the plovers see their broods threatened. During such fights, it occurs that chicks get injured or even killed.[29] When approached by a predator, chicks usually try to find a spot where they can hide, crouch down and stay motionless to remain unseen. When they are older, they try to run away with their parents.

Nesting and incubation

Kentish plovers either nest solitarily or in a loose semicolonial manner. They are ground-nesting birds that lay their eggs in small shallow scrapes prepared by the male during courtship on the bare ground. Selection of the breeding ground is essential for the survival of nests and broods; nests are placed near the water on bare earth or in sparse vegetation; often on slightly elevated sites in order to have a good view of the surroundings to spot predators from a distance or near small bushes, plants or grass clusters,[30] where the eggs are partly sheltered from predators. Nests are filled with nest material i.e. pebble stones, small parts of shells, fish bones, small twigs, grass and other debris.[8] The modal clutch size comprises three eggs, although some nests are already completed with one or two eggs. In fresh or incomplete nests, the eggs tend to be fully exposed, but as the incubation period progresses, the amount of nest material increases and the eggs become practically completely covered.[1] During the incubation period, the Kentish plover recesses for variable periods of time mainly to forage or to perform other activities essential for self-maintenance. To compensate for the resulting lack of presence and increased predation risk, they use nest materials to cover and hence camouflage the eggs and keep them insulated.[31] Kentish plovers regulate the amount of nest material actively. This was shown experimentally in a study by increasing or decreasing the amount of nest material artificially. Within 24hrs, the plovers had restored the amount of nest material back to original.[8] This is of advantage because nest materials help a good insulation of eggs, therefore preventing egg temperature fluctuations [32]) (hence avoiding embryo hypothermia) and reducing the energetic costs of incubation for the parents.[32] By regulating the amount of nest material, the Kentish plovers balances the advantages i.e. insulation and anti-predator defence and the disadvantages of nest material i.e. overheating.[8] Incubation is the process by which the eggs are kept at optimal temperature i.e. between 37 °C and 38 °C for the embryonic development of birds with most of the heat deriving from the incubating bird.[33] Kentish plover eggs are incubated for 20–25 days by both sexes; females mostly incubate during the day whilst males incubate during the night.[34] Female Kentish plovers usually lose mass during the day, which is unexpected since they get relieved by the males for a variable amount of time. The loss would be much higher if the females were to incubate alone. This loss is a cost of incubation due to the depletion of fat stores and the evaporation of water.[35]

Parental care

Parental care is variable within birds and the Kentish plover has a slightly different mechanism to other shorebirds. As discussed above, both parents incubate the eggs, however both parents do not always stick around once the eggs have hatched. It is not unusual for one parent to leave the chicks after a variable amount of time; this is referred to as brood desertion. Brood desertion is the ‘termination of care, by either one or both parents, before the offspring are capable of surviving independently’ [36] and usually occurs after one week of the brood being accompanied by both parents. Brood desertion has been observed in both males and females, however females desert the brood significantly more frequently than males.[25] Studies have shown that both the male and female Kentish plover can provide adequate care for their brood on their own, so it is not the differences in the ability of the parents that determines which parent deserts the brood and which stays to care for the chicks. However, studies have also shown that after desertion females have a larger chance of breeding success than males, potentially due to many Kentish plover populations maintaining a male-biased OSR (operational sex ratio - the ratio of males actively breeding to females). Therefore, is it hypothesized that the amount of reproductive success gained by desertion is what actually determines who deserts the brood,.[37][15] In short, males and females can care for their brood equally, however females gain more by deserting their brood than males, resulting in a higher amount of female desertion over male. The non-deserting parent can continue to brood their chicks up to 80% of the time for over 20 days after hatching, as precocial young are vulnerable and exposed to external temperatures.

If the parent bird feels that the eggs or chicks are under attack, then it will feign injury in order to divert attention towards itself. [38]

Calls

The alarm call, referred to as kittup call, is often heard both on the ground and in the air and can occur on its own, or paired with a tweet, heard as too-eet. The threat note is described as a "twanging, metallic, dwee-dwee-dweedweedwee sound".[39]

Feeding

Kentish plovers either forage individually or in loose flocks of 20-30 individuals (outside the breeding season), and occasionally can incorporate into larger flocks of up to 260 individuals of multiple species.[40][41] Their main source of food consists of miniature aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates such as insects and their larvae (e.g. beetles, grasshoppers or flies), molluscs, crustaceans, spiders and marine worms.[40] They are obligate visual foragers and often feed at the shoreline of lakes, lagoons or ponds in invertebrate-rich moist-soil areas.[42] They forage by looking, stopping or running and then pecking to catch the prey, but also probe the sand to search for prey, or catch flies by holding their mouths open.[43] The Kentish plover's capability of identifying cues for prey is influenced by light, wind and rain.[44] At night, their ability of finding prey might be restricted, but plovers have been shown to have a good nocturnal vision due to their large eyes and enhanced retinal visual sensitivity,.[45][46]

Status and conservation

Status

The Kentish plover is classified as least concern on the Red List because it has a very large population range.

The global population size of the Kentish plover is continuously declining although for some populations the trends are unknown.[47] The European population is estimated at 43,000-70,000 individuals, forming around 15% of the global population (estimated at 100,000-500,000 individuals).[48]

Threats

A major threat to this species is habitat loss and disturbance. Human activity such as tourists walking through protected areas, pollution, unsustainable harvesting and urbanisation can destroy nesting sites. Plover populations can also be affected by rural human activity, for example fishermen walking through protected plover breeding sites, bringing large numbers of dogs with them- a known predator of plover eggs. Breeding birds respond to human disturbance disproportionately when dogs are present,[49] as these situations are interpreted in a context of greater risk of predation.[50] Natural predators are also a problem, as many of these predators appear to thrive unnaturally well in the presence of plover breeding grounds, such as the brown-necked raven (Corvus ruficollis) in Maio, Cape Verde, the White-tailed Mongoose (Ichneumia albicauda) in Saudi Arabia, and the Grey Monitors (Varanus griseus) in Al-Wathba Wetland Reserve. It is thought that the high amount of prey available to these predators attracts them into the breeding grounds- an effect named the 'honey pot',[51][48][52] Global warming and climate change also plays a role in the decline of areas available for plovers to breed and reside in. It is known that the Kentish plover prefers to build its nests on low-elevated land close to water, and a study untaken in Saudi Arabia discovered that 11% of nests in the study site were in fact below sea level, therefore rising sea levels are predicted to have disastrous consequences for these low-sitting nests,.[7][53]

Management

The Kentish plover is currently on the Annex I of the EU Birds Directive and Annex II of the Bern Convention.[48] Conservation actions proposed to protect the species include the conservation of their natural habitat by creating or elaborating protected areas at breeding sites. This is essential to stop pollution, land reclamation and urbanisation. Human interaction should be controlled and kept at a minimum.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Székely, T., A. Argüelles-Ticó, A. Kosztolányi and C. Küpper. 2011. Practical guide for investigating breeding ecology of Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus, Unpublished Report, University of Bath

- ↑ del Hoyo, J., Collar, N.J., Christie, D.A., Elliott, A. and Fishpool, L.D.C. 2014. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Lynx Edicions BirdLife International, Barcelona, Spain and Cambridge, UK

- ↑ Message, S. and Taylor, D.W. 2005. Field guide to the waders of Europe, Asia and North America. London: Christopher Helm Publishers.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Meininger, P., Székely, T., and Scott, D. 2009. Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus. In: Delaney, S., Scott, D. A., Dodman, T., Stroud, D. A. An atlas of wader populations in Africa and Eurasia. Wetlands International, pp 229-235

- ↑ Kosztolányi, A., Javed, S., Küpper, C., Cuthill, I., Al Shamsi, A. and Székely, T. 2009. Breeding ecology of Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus in an extremely hot environment, Bird Study, 56:2, 244-252

- ↑ "Focus on: Kentish Plover" (in en). 2020-04-30. https://www.birdguides.com/articles/species-profiles/focus-on-kentish-plover/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 AlRashidi, M., Long, P.R., O’Connell, M., Shobrak, M. & Székely, T. 2011. Use of remote sensing to identify suitable breeding habitat for the Kentish plover and estimate population size along the western coast of Saudi Arabia. Wader Study Group Bull. 118(1): 32–39

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Szentirmai, I. and Székely, T. 2002. Do kentish plovers regulate the amount of their nest material? An experimental test, Behaviour, 139(6), pp. 847–859

- ↑ Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) European birds online guide (no date) Available at: http://www.avibirds.com/html/Kentish_Plover.html (Accessed: 16 January 2017)

- ↑ Székely, T., Karsai, I. and Kovazs, S. 1993. Availability of Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) prey on a Central Hungarian grassland. Ornis Hung. 3:41-48

- ↑ Küpper, Clemens; Augustin, Jakob; Kosztolányi, András; Burke, Terry; Figuerola, Jordi; Székely, Tamás (2009). "Kentish versus snowy plover: phenotypic and genetic analyses of Charadrius alexandrinus reveal divergence of Eurasian and American subspecies". Auk 126 (4): 839–852. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.08174. https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/41193/1/Kupper_08_174.pdf.

- ↑ "'Hanuman Plover' - New bird species discovered in Sri Lanka" (in en). 2020-12-15. https://www.newsfirst.lk/2020/12/15/hanuman-plover-new-bird-species-discovered-in-sri-lanka/.

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ibi.13220

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Argüelles-Ticó, A., Küpper, C., Kelsh, R.N., Kosztolányi, A., Székely, T. and van Dijk, R.E. 2015. Geographic variation in breeding system and environment predicts melanin-based plumage ornamentation of male and female Kentish plovers, Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 70(1), pp. 49–60

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Szekely, T. 1999. Brood desertion in Kentish plover: Sex differences in remating opportunities, Behavioral Ecology, 10(2), pp. 185–190

- ↑ Kis, J. and Székely, T. 2003. Sexually dimorphic breast-feathers in the Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus. Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 49, 103-110

- ↑ Wolf, B. O. and Walsberg, G. E. 2000. The role of plumage in heat transfer processes of birds. American Zoologist, 40, 575-584

- ↑ Hill, G.E. 1993. Geographic variation in the carotenoid plumage pigmentation of male house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus). Biol J Linn Soc 49:63–86

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Vincze, O., Székely, T., Küpper, C., AlRashidi, M., Amat, J.A. et al. 2013. Local Environment but Not Genetic Differentiation Influences Biparental Care in Ten Plover Populations. PLoS ONE 8(4

- ↑ "OzAnimals". https://www.ozanimals.com/Bird/Kentish-Plover/Charadrius/alexandrinus.html.

- ↑ "BirdLife". http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/barc/SUMM343.htm.

- ↑ Meininger, P., Székely, T., and Scott, D. 2009. Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus. In: Delaney, S., Scott, D. A., Dodman, T., Stroud, D. A. An atlas of wader populations in Africa and Eurasia. Wetlands International, pp 229-235.

- ↑ Kosztolányi, A., Székely, T. and Cuthill, I.C. 2007. The function of habitat change during brood-rearing in the precocial Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus, acta ethologica, 10(2), pp. 73–79

- ↑ Fraga, R.M. and Amat, J.A. 1996. Breeding biology of a Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) population in an inland saline lake. Available at: http://www.ardeola.org/files/319.pdf

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Székely, T. and Lessells, C. M. 1993. Mate change by Kentish Plovers Charadrius alexandrinus. Ornis Scand.2 4: 317-322

- ↑ Blomqvist, D., Andersson, M., Küpper, C., Cuthill, I.C., Kis, J., Lanctot, R.B., Sandercock, B.K., Székely, T., Wallander, J. and Kempenaers, B. 2002. Genetic similarity between mates and extra-pair parentage in three species of shorebirds, Nature. 419(6907), pp. 613–615

- ↑ Carmona-Isunza, M.C., Küpper, C., Serrano-Meneses, M.A. and Székely, T. 2015. Courtship behavior differs between monogamous and polygamous plovers, Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 69(12), pp. 2035–2042

- ↑ Gómez-Serrano, Miguel Ángel; López-López, Pascual (2017). "Deceiving predators: linking distraction behavior with nest survival in a ground-nesting bird". Behavioral Ecology 28 (1): 260–269. doi:10.1093/beheco/arw157. https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/28/1/260/2453523.

- ↑ Kosztolányi & Székely, pers. obs.

- ↑ Snow, D.W. and Perrins, C.M. 1998. The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume 1: Non-Passerines. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- ↑ Masero, José A.; Monsa, Rocío; Amat, Juan A. (2012). "Dual function of egg-covering in the Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus". Behaviour 149 (8): 881–895. doi:10.1163/1568539x-00003008.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Reid, J.M., Cresswell, W., Holt, S., Mellanby, R.J., Whitéeld, D.P. and Ruxton, G.D. 2002. Nest scrape design and clutch heat loss in pectoral sandpipers (Calidris melanotos). Functional Ecology, 16(3), 305-312

- ↑ Deeming, D.C. 2002. Importance and evolution of incubation in avian reproduction. In: Avian incubation: behaviour, environment, and evolution. Deeming, D.C., ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 1-7

- ↑ Kosztolányi, A. and Székely, T. 2002. Using a transponder system to monitor incubation routines of snowy plovers. J. Field Ornithol. (in press)

- ↑ Szentirmai, I., Kosztolányi, A. and Székely, T. 2001. Daily changes in body mass of incubating Kentish Plovers. Ornis Hung. 11: 27-32

- ↑ Fujioka, M. 1989. Mate and nestling desertion in colonial little egrets. Auk 106:292-302

- ↑ Cuthill, I., Székely, T., McNamara, J. and Houston, A. 2002. Why do birds get divorced? NERC News Spring: 6-7

- ↑ "feign". https://www.saygaomei.com.tw/web_en/species/058/index.html.

- ↑ Simmons, K. E. L. 1955. The significance of voice in the behaviour of the Little Ringed and Kentish plovers. Brit. Birds 48: 106-114

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., and Sargatal, J. 1996. Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions Barcelona, Spain

- ↑ Urban, E.K., Fry, C.H. and Keith, S. 1986. The Birds of Africa, Volume II. Academic Press, London

- ↑ Anderson, J.T., Smith, L.M. 2000. Invertebrate response to moist-soil man- agement of playa wetlands. Ecol Appl 10:550–558

- ↑ European birds online guide (no date) Available at: http://www.avibirds.com/html/Kentish_Plover.html (Accessed: 16 January 2017)

- ↑ McNeil, R., Drapeau, P. and Goss-Custard, J.D. 1992. The occurrence and adaptive significance of nocturnal habits in waterfowl. Biol Rev 67:381–419

- ↑ Rojas de Azuaje, L.M., Tai, S. and McNei, l. R. 1993. Comparison of rod/cone ratio in three species of shorebirds having different nocturnal foraging strategies. Auk. 110:141–145

- ↑ Thomas, R.J., Székely, T., Powel,l R.F. and Cuthill, I.C. 2006. Eye size, foraging methods and the timing of foraging in shorebirds. Funct Ecol 20:157–165

- ↑ Wetlands International. 2006. Waterbird Population Estimates – Fourth Edition. Wetlands International, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 BirdLife International. 2017. Species factsheet: Charadrius alexandrinus. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org

- ↑ Gómez‐Serrano, Miguel Ángel (2021). "Four-legged foes: dogs disturb nesting plovers more than people do on tourist beaches" (in en). Ibis 163 (2): 338–352. doi:10.1111/ibi.12879. ISSN 1474-919X.

- ↑ Gómez-Serrano, Miguel Ángel; López-López, Pascual (2014-09-10). "Nest Site Selection by Kentish Plover Suggests a Trade-Off between Nest-Crypsis and Predator Detection Strategies" (in en). PLOS ONE 9 (9): e107121. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107121. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 25208045. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j7121G.

- ↑ AlRashidi, M., Kosztolányi, A., Shobrak, M. and Székely, T. 2011. Breeding ecology of the Kentish Plover, Charadrius alexandrinus, in the Farasan islands, Saudi Arabia, Zoology in the Middle East. 53(1), pp. 15–24

- ↑ Rice, R., Engel, N. 2016. Breeding ecology of Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus in Maio, Cape Verde. Unpublished Fieldwork Report, University of Bath

- ↑ AlRashidi, M., Shobrak, M., Al-Eissa, M.S. and Székely, T. 2012. Integrating spatial data and shorebird nesting locations to predict the potential future impact of global warming on coastal habitats: A case study on Farasan islands, Saudi Arabia, Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 19(3), pp. 311–315

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charadrius alexandrinus. |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.2 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Charadrius alexandrinus alexandrinus Linnaeus, 1758 at ITIS

Wikidata ☰ Q18855 entry