Biology:Vagenetia

Vagenetia or Vagenitia (Greek: Βαγενετία, Βαγενιτία) was a medieval region on the coast of Epirus, roughly corresponding to modern Thesprotia. The region likely derived its name from the Slavic tribe of the Baiounitai. It is first attested as a sclavinia under some sort of Byzantine control in the 8th/9th centuries. It passed under Bulgarian rule in the late 9th century, and returned to Byzantine rule in the 11th. It passed to the Despotate of Epirus after 1204, where it formed a separate province. Vagenetia came under Albanian rule in the 1360s, until conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1430.

History

The region's name derives from the Slavic tribe of the Baiounitai, who appear in the early 7th century during the Slavic invasions of the Balkans.[1] Already during the 8th century, the Byzantine Empire tried to re-impose some control over the region, as a seal of office attests the presence of a civil governor ("Theodore, basilikos spatharios and archon of Vagenitia"), but the reading of the latter is not certain.[1][2] Byzantine administration is securely attested towards the end of the 9th century, with the presence of both a bishop called Stephen in the Fourth Council of Constantinople in 879, and the seal of a civil governor (the basilikos protospatharios and archon Ilarion) from the turn of the 10th century.[1][3]

The historian Predrag Komatina suggests that the bishopric was an "ethnic" bishopric for the Baiounitai (but with Greek-language liturgy), which then was succeeded by the Slavic-language episcopate of Clement of Ohrid (893–916), which was not organized on a territorial, but on an ethnic basis, and had no fixed centre. Clement's roving episcopate was gradually replaced by bishoprics based in the various cities of the area.[4] At the time of Clement's activity in the area, and during the early 10th century, Vagenetia and its wider area was ruled by the First Bulgarian Empire; thus the local church also became part of the Bulgarian Church, and later of the Archbishopric of Ohrid.[4] The ultimate descendant of the bishopric of Vagenetia was likely the see of Himara.[5]

Vagenetia is next mentioned in literary sources in the Alexiad, which describes how, in 1082, the Italo-Normans under Bohemund crossed the region to capture Ioannina.[1][6] In the Partitio Romaniae of 1204, Vagenetia appears as a chartoularaton (a special district type indicating Slavic settlement) in the province of Dyrrhachium.[1][6]

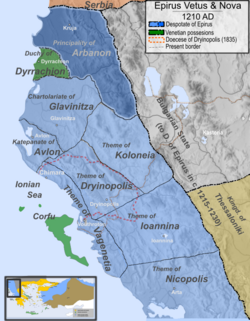

In 1205, it is listed by Marino Zeno, the Podestà of Constantinople, among the territories accorded to the Republic of Venice by the Partitio. In Zeno's account, it is a separate province, distinct from Dyrrhachium, and in turn includes the chartoularaton of Glyky, north of Arta (which previously probably belonged to the Byzantine province of Nicopolis.[7] Apart from the region of Dyrrhachium, however, the Venetians failed to consolidate their rule over most of the lands accorded to them in Epirus, and possession of Vagenetia passed to the Despotate of Epirus, where it is attested as a separate province (provincia in Latin, thema in Greek) within the Epirote state as early as the 1210 treaty between Michael I Komnenos Doukas and Venice.[1][8]

In 1228, Theodore Komnenos Doukas confirmed possession of lands "on the island of Corfu and the thema of Vagenetia" to the Metropolitan of Corfu.[9] In 1292, the coasts of the province were raided by Genoese ships in Byzantine employ,[1][9] and two years later, the province was promised to Philip of Taranto as part of the dowry of Thamar Angelina Komnene.[1][9][10] Still, the Despot of Epirus Thomas I Komnenos Doukas was ascribed the title of "Duke of Vagenetia" in a Venetian document in 1313.[1][11] In 1315, a document of the Patriarchate of Constantinople records that Vagenetia belonged to the bishopric of Himara.[9]

During the Albanian invasions of Epirus in the 1360s, many of the local Greeks fled to Ioannina.[1] In 1382, the Albanian ruler John Spata gave the region, along with Bela and Dryinopolis, to his son-in-law Marchesino.[1][12] In the early 1400s, the local Albanian ruler John Zenevisi is referred to in some Venetian documents as the "sebastokrator of Vagenetia".[1][13][12] His grandson, Simon Zenevisi, with Venetian backing built the fortress of Strovili "at the cape of Vagenetia" across the island of Corfu in 1443.[14][12]

Most of Epirus fell under Ottoman rule in 1430,[15][16] and in 1431, the Ottoman cadaster attests the existence of a province of Vayonetya.[12][17] The name survived to the end of the century in various variants (Viyanite, Viyantiye), but the name vanishes thereafter,[12] apart from a village Vagenetion south of Ioannina and an isolated reference to a "Greater Vagenetia" (μεγάλη Βαγενετία) in the 17th century.[18]

Geography

According to the historian Stojan Novaković, followed by Peter Soustal and Johannes Koder in the Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Vagenetia was the coastal strip between the Ionian Sea and the Pindus Mountains that extended from Himara in the north to Margariti in the south.[1][19] However, Komatina objects that these boundaries reflect the situation in the 13th–14th centuries, and that the earlier, original region, the chartoularaton of Vagenetia, was much smaller. Komatina points out that after 1205, Vagenetia came to include the district of Glyky to the south, but the original territory was just the northern part of the expanded province. Komatina identifies this with the territory referred to by John Apokaukos as "Lesser Vagenetia" (μικρὰ Βαγενετία), namely the area around the valley of the Aoös. This also corresponds to the Ottoman province, which comprised Himara and its hinterlands, with Delvina as its centre.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 119.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, p. 84.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 83, 84–85.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Komatina 2016, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 92–95.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Komatina 2016, p. 85.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 86, 90.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Komatina 2016, p. 88.

- ↑ Nicol 1984, p. 47.

- ↑ Nicol 1984, p. 80.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Komatina 2016, p. 89.

- ↑ Nicol 1984, pp. 163–164, 175–176, 179ff..

- ↑ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 119, 265.

- ↑ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Nicol 1984, pp. 197ff..

- ↑ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 76, 119.

- ↑ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Komatina 2016, pp. 89–91.

Sources

- Komatina, Predrag (2016). "ОБЛАСТ ВAГЕНИТИЈА И ЕПИСКОПИЈА СВ. КЛИМЕНТА" (in Serbian). Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta LIII (53): 83–100. doi:10.2298/ZRVI1653083K. http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0584-9888/2016/0584-98881653083K.pdf.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1984). The Despotate of Epiros 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521261906. https://books.google.com/books?id=XIj0FfKto9AC.

|