Place:First Bulgarian Empire

First Bulgarian Empire ц︢рьство бл︢гарское | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 681–1018 | |||||||||||||

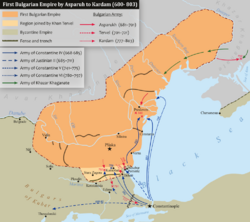

First Bulgarian Empire, late 9th century (894). | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Pliska (681–893), Preslav (893–968/972), Skopje, Ohrid, Bitola (until 1018) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism, Slavic paganism (681–864), Orthodox Christianity (state religion from 864) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

• 681–700 | Asparuh (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1015–1018 | Ivan Vladislav of Bulgaria (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

• Asparuh arrives and defeats Eastern Rome at the Battle of Ongal | 680 | ||||||||||||

• New Bulgarian state recognized by Eastern Rome | 681 | ||||||||||||

• Christianisation | 864 | ||||||||||||

• Adoption of Old Bulgarian as a national language | 893 | ||||||||||||

• Simeon I assumes the title of Tsar (Emperor) | 913 | ||||||||||||

• Theme Bulgaria established in Byzantine Empire | 1018 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 830[1] | 593,000 km2 (229,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 927[2] | 807,000 km2 (312,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1000[3] | 487,000 km2 (188,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BG | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The First Bulgarian Empire (Old Bulgarian: ц︢рьство бл︢гарское, ts'rstvo bl'garskoe) was a medieval Bulgarian state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 681 when Bulgar tribes led by Asparuh moved to the northeastern Balkans. There they secured Byzantine recognition of their right to settle south of the Danube by defeating – possibly with the help of local South Slavic tribes – the Byzantine army led by Constantine IV. At the height of its power, Bulgaria spread from the Danube Bend to the Black Sea and from the Dnieper River to the Adriatic Sea.

As the state solidified its position in the Balkans, it entered into a centuries-long interaction, sometimes friendly and sometimes hostile, with the Byzantine Empire. Bulgaria emerged as Byzantium's chief antagonist to its north, resulting in several wars. The two powers also enjoyed periods of peace and alliance, most notably during the Second Arab siege of Constantinople, where the Bulgarian army broke the siege and destroyed the Arab army, thus preventing an Arab invasion of Southeastern Europe. Byzantium had a strong cultural influence on Bulgaria, which also led to the eventual adoption of Christianity in 864. After the disintegration of the Avar Khaganate, the country expanded its territory northwest to the Pannonian Plain. Later the Bulgarians confronted the advance of the Pechenegs and Cumans, and achieved a decisive victory over the Magyars, forcing them to establish themselves permanently in Pannonia.

During the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Simeon I achieved a string of victories over the Byzantines. Thereafter, he was recognized with the title of Emperor, and proceeded to expand the state to its greatest extent. After the annihilation of the Byzantine army in the battle of Anchialus in 917, the Bulgarians laid siege to Constantinople in 923 and 924. The Byzantines, however, eventually recovered, and in 1014, under Basil II, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Bulgarians at the Battle of Kleidion. By 1018, the last Bulgarian strongholds had surrendered to the Byzantine Empire, and the First Bulgarian Empire had ceased to exist. It was succeeded by the Second Bulgarian Empire in 1185.

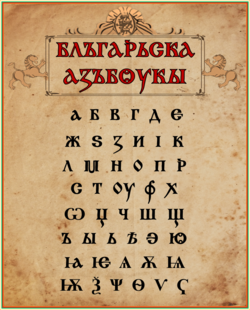

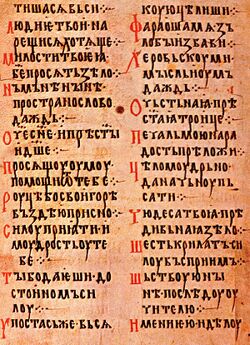

After the adoption of Christianity, Bulgaria became the cultural center of Slavic Europe. Its leading cultural position was further consolidated with the invention of the Glagolitic and Early Cyrillic alphabets shortly after in the capital Preslav, and literature produced in Old Bulgarian soon began spreading north. Old Bulgarian became the lingua franca of much of Eastern Europe and it came to be known as Old Church Slavonic. In 927, the fully independent Bulgarian Patriarchate was officially recognized.

The ruling Bulgars and other non-Slavic tribes in the empire gradually mixed and adopted the prevailing Slavic language, thus gradually forming the Bulgarian nation from the 7th century to the 9th century. Since the late 9th century, the names Bulgarians and Bulgarian gained prevalence and became permanent designations for the local population, both in literature and in common parlance. The development of Old Church Slavonic literacy had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighbouring cultures, while stimulating the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity.

Nomenclature

The First Bulgarian Empire became known simply as Bulgaria[4] since its recognition by the Byzantine Empire in 681. Some historians use the terms Danube Bulgaria,[5] First Bulgarian State,[6][7] or First Bulgarian Tsardom (Empire). Between 681 and 864 the country was also known as the Bulgarian Khanate,[8] Danube Bulgarian Khanate, or Danube Bulgar Khanate[9][10] in order to differentiate it from Volga Bulgaria, which emerged from another Bulgar group. During its early existence, the country was also called the Bulgar state[11] or Bulgar Khaghanate.[12] Between 864 and 917/927, the country was known as the Principality of Bulgaria or Knyazhestvo Bulgaria. In English language sources, the country is often known as the Bulgarian Empire.[13]

Background

The Balkans during the early Migration Period

Parts of the eastern Balkan Peninsula were in antiquity inhabited by the Thracians who were a group of Indo-European tribes.[14] The whole region as far north as the Danube River was gradually incorporated into the Roman Empire by the 1st century AD.[15] The decline of the Roman Empire after the 3rd century AD and the continuous invasions of Goths and Huns left much of the region devastated, depopulated and in economic decline by the 5th century.[16] The surviving eastern half of the Roman Empire, called by later historians the Byzantine Empire, could not exercise effective control in these territories other than in the coastal areas and certain cities in the interior. Nonetheless, it never relinquished the claim to the whole region up to the Danube. A series of administrative, legislative, military and economic reforms somewhat improved the situation but despite these reforms disorder continued in much of the Balkans.[17] The reign of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) saw temporary recovery of control and reconstruction of a number of fortresses but after his death the empire was unable to face the threat of the Slavs due to the significant reduction of revenue and manpower.[18]

Slavic migrations to the Balkans

The Slavs, of Indo-European origin, were first mentioned in written sources to inhabit the territories to the north of the Danube in the 5th century AD but most historians agree that they had arrived earlier.[19] The group of Slavs that came to be known as the South Slavs was divided into Antes and Sclaveni who spoke the same language.[19][20] The Slavic incursions in the Balkans increased during the second half of Justinian I's reign and while these were initially pillaging raids, large-scale settlement began in the 570s and 580s.[20][21][22] This migration is associated with the arrival of the Avars who settled in the plains of Pannonia between the rivers Danube and Tisza in the 560s subjugating various Bulgar and Slavic tribes in the process.[20][23]

Consumed in bitter wars with the Persian Sasanian Empire in the east, the Byzantines had few resources with which to confront the Slavs.[24][25] The Slavs came in large numbers and the lack of political organisation made it very difficult to stop them because there was no political leader to defeat in battle and thereby force their retreat.[24] As the wars with Persia persisted, the 610s and 620s saw a new and even larger migration wave with the Slavs penetrating further south into the Balkans, reaching Thessaly, Thrace and Peloponnese and raiding some islands in the Aegean Sea.[26] The Byzantines held out in Salonica and a number of coastal towns but beyond these areas the imperial authority in the Balkans disappeared.[27]

The Bulgars

The Bulgars were semi-nomadic warrior tribes originating from Central Asia whose exact ethnic origin is controversial. They spoke a form of Turkic language and during their migration westwards they absorbed other ethnic groups and cultural influences, including Hunnic, Iranian and Indo-European people.[28][29] The Bulgars included the tribes of Onogurs, Utigurs and Kutrigurs, among others.[30][31]

The first clear mention of the Bulgars in written sources dates from 480, when they served as the allies of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (r. 474–491) against the Ostrogoths[32] although an obscure reference to Ziezi ex quo Vulgares, with Ziezi being an offspring of Biblical Shem, son of Noah, is in the Chronography of 354.[33][34] In the 490s the Kutrigurs had moved west of the Black Sea while the Utigurs inhabited the steppes to the east of them. In the first half of the 6th century the Bulgars occasionally raided the Byzantine Empire but in the second half of the century the Kutrigurs were subjugated by the Avar Khaganate and the Utigurs came under the rule of the Western Turkic Khaganate.[35][36]

As the power of the Western Turks faded in the 600s the Avars reasserted their domination over the Bulgars. Between 630 and 635 Khan Kubrat of the Dulo clan managed to unite the main Bulgar tribes and to declare independence from the Avars, creating a powerful confederation called Old Great Bulgaria, also known as Patria Onoguria, between the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Caucasus.[37][38] Kubrat, who was baptised in Constantinople in 619, concluded an alliance with the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) and the two countries remained in good relations until Kubrat's death between 650 and 663.[37] Kubrat fought with the Khazars in the east but after his demise Old Great Bulgaria disintegrated under strong Khazar pressure in 668[39] and his five sons parted with their followers. The eldest Batbayan remained in his homeland as Kubrat's successor and eventually became a Khazar vassal. The second brother Kotrag migrated to the middle Volga region and founded Volga Bulgaria.[40] The third brother Asparuh led his people west to the lower Danube.[37] The fourth one, Kuber, initially settled in Pannonia under Avar suzerainty but revolted and moved to the region of Macedonia, while the fifth brother Alcek settled in central Italy.[41][42]

History

Establishment and consolidation

The Bulgars of Asparuh moved westwards to what is now Bessarabia, subdued the territories to the north of the Danube in modern Wallachia, and established themselves in the Danube Delta.[43] In the 670s they crossed the Danube into Scythia Minor, nominally a Byzantine province, whose steppe grasslands and pastures were important for the large herd stocks of the Bulgars in addition to the grazing grounds to the west of the Dniester River already under their control.[42][44][45] In 680 the Byzantine Emperor Constantine IV (r. 668–685), having recently defeated the Arabs, led an expedition at the head of a huge army and fleet to drive off the Bulgars but suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of Asparuh at Onglos, a swampy region in or around the Danube Delta where the Bulgars had set a fortified camp.[43][46] The Bulgars advanced south, crossed the Balkan Mountains and invaded Thrace.[47] In 681, the Byzantines were compelled to sign a humiliating peace treaty, forcing them to acknowledge Bulgaria as an independent state, to cede the territories to the north of the Balkan Mountains and to pay an annual tribute.[43][48] In his universal chronicle the Western European author Sigebert of Gembloux remarked that the Bulgarian state was established in 680.[49] This was the first state that the empire recognised in the Balkans and the first time it legally surrendered claims to part of its Balkan dominions.[43] The Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor wrote of the treaty:

...the Emperor [Constantine IV] signed peace with them [the Bulgars], and agreed to pay them tribute for shame of the Romans and for our many sins. For it was wondrous for faraway and close peoples to hear that he, who made everyone pay him tribute – to the east and to the west, to the north and to the south, had been defeated by this unclean and newly emerged people.[47][50]

The relations between the Bulgars and the local Slavs is a matter of debate depending on the interpretation of the Byzantine sources.[51] Vasil Zlatarski asserts that they concluded a treaty[52] but most historians agree that they were subjugated.[51][53] The Bulgars were superior organisationally and militarily and came to dominate politically the new state but there was cooperation between them and the Slavs for the protection of the country. The Slavs were allowed to retain their chiefs, to abide to their customs and in return they were to pay tribute in kind and to provide foot soldiers for the army.[54] The Seven Slavic tribes were relocated to the west to protect the frontier with the Avar Khaganate, while the Severi were resettled in the eastern Balkan Mountains to guard the passes to the Byzantine Empire.[51] The number of Asparuh's Bulgars is difficult to estimate. Vasil Zlatarski and John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. suggest that they were not particularly numerous, numbering some 10,000,[55][56] while Steven Runciman considers that the tribe must had been of considerable dimensions.[57] The Bulgars settled mainly in the north-east, establishing the capital at Pliska, which was initially a colossal encampment of 23 km2 protected with earthen ramparts.[55][45]

To the north-east the war with the Khazars persisted and in 700 Khan Asparuh perished in battle with them.[58][59] Despite this setback the consolidation of the country continued under Asparuh's successor, Khan Tervel (r. 700–721). In 705 he assisted the deposed Byzantine Emperor Justinian II in regaining his throne in return for the Zagore region of Northern Thrace, the first expansion of Bulgaria to the south of the Balkan mountains.[59] In addition Tervel obtained the title Caesar[60] and, having been enthroned alongside the Emperor, received the obeisance of the citizenry of Constantinople and numerous gifts.[59][60] However, three years later, Justinian tried to regain the ceded territory by force, but his army was defeated at Anchialus.[61] Skirmishes continued until 716 when Khan Tervel signed an important agreement with Byzantium that defined the borders and the Byzantine tribute, regulated trade relations and provided for the exchange of prisoners and fugitives.[60][62] When the Arabs laid siege to Constantinople in 717–718 Tervel dispatched his army to help the besieged city. In the decisive battle before the Walls of Constantinople the Bulgarians slaughtered between 22,000[63] and 30,000[64] Arabs forcing them to abandon the undertaking. Most historians primarily attribute the Byzantine-Bulgarian victory with stopping the Arab offensives against Europe.[62]

Internal instability and struggle for survival

With the demise of Khan Sevar (r. 738–753) the ruling Dulo clan died out and the Khanate fell into a long political crisis during which the young country was on the verge of destruction. In just fifteen years seven Khans reigned, and all of them were murdered. The only surviving sources of this period are Byzantine and present only the Byzantine point of view of the ensuing political turmoil in Bulgaria.[62] They describe two factions struggling for power – one that sought peaceful relations with the Empire, which was dominant until 755, and one that favoured war.[62] These sources present the relations with the Byzantine Empire as the main issue in this internal struggle and do not mention the other reasons, which could have been more important for the Bulgarian elite.[62] It is likely that the relationship between the politically dominant Bulgars and the more numerous Slavs was the main issue behind the struggle but there is no evidence about the aims of the rival factions.[65] Zlatarski speculates that the old Bulgar military aristocracy was leaning towards war while other Bulgars supported by the majority of the Slavs were inclined for peace with Byzantium.[66]

The internal instability was used by the "soldier Emperor" Constantine V (r. 745–775), who launched nine major campaigns aiming to eliminate Bulgaria.[67] Having contained the Arab threat during the first part of his reign, Constantine V was able to concentrate his forces on Bulgaria after 755.[68] He defeated the Bulgarians at Marcellae in 756, Anchialus in 763 and Berzitia in 774, but lost the battle of the Rishki Pass in 759 in addition to hundreds of ships lost to storms in the Black Sea. The Byzantine military successes further exacerbated the crisis in Bulgaria, but also rallied together many different factions to resist the Byzantines, as shown at the council of 766 when the nobility and the "armed people" denounced Khan Sabin with the words "Thanks to you, the Romans will enslave Bulgaria!".[68][69] In 774 Khan Telerig (r. 768–777) tricked Constantine V into revealing his spies at the Bulgarian court in Pliska and had them all executed.[68] The next year Constantine V died during a retaliatory campaign against Bulgaria.[70][71] Despite being able to defeat the Bulgarians several times the Byzantines were able neither to conquer Bulgaria, nor to impose their suzerainty and a lasting peace, which is a testimony to the resilience, fighting skills and ideological coherence of the Bulgarian state.[72][73] The devastation brought to the country by the nine campaigns of Constantine V firmly rallied the Slavs behind the Bulgars and greatly increased the dislike of the Byzantines, turning Bulgaria into a hostile neighbour.[72] The hostilities continued until 792 when Khan Kardam (r. 777–803) achieved an important victory in the battle of Marcellae, forcing the Byzantines once again to pay tribute to the Khans.[74] As a result of the victory, the crisis was finally overcome, and Bulgaria entered the new century stable, stronger, and consolidated.[75]

Territorial expansion

During the reign of Khan Krum (r. 803–814) Bulgaria doubled in size and expanded southward and to the northwest, occupying the lands along the middle Danube and Transylvania. Between 804 and 806 the Bulgarian armies thoroughly eliminated the Avar Khaganate, which had suffered a crippling blow by the Franks in 796, and a border with the Frankish Empire was established along the middle Danube or Tisza.[72] Prompted by the Byzantine moves to consolidate their hold on the Slavs in Macedonia and northern Greece and in response to a Byzantine raid against the country, the Bulgarians confronted the Byzantine Empire.[76][77] In 808 they raided the valley of the Struma River, defeating a Byzantine army, and in 809 captured the important city of Serdica (modern Sofia).[76][78][79] In 811 the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I launched a massive offensive against Bulgaria, seized, plundered and burned down the capital Pliska but on the way back the Byzantine army was decisively defeated in the battle of the Varbitsa Pass. Nicephorus I himself was slain along with most of his troops, and his skull was lined with silver and used as a drinking cup.[80][81] Krum took the initiative and in 812 moved the war towards Thrace, capturing the key Black Sea port of Messembria and defeating the Byzantines once more at Versinikia in 813 before proposing a generous peace settlement.[78][82] However, during the negotiations the Byzantines attempted to assassinate Krum. In response, the Bulgarians pillaged Eastern Thrace and seized the important city of Adrianople, resettling its 10,000 inhabitants in "Bulgaria across the Danube".[83][84] Krum made extensive preparations to capture Constantinople: 5,000 iron-plated wagons were built to carry the siege equipment; the Byzantines even pleaded for help from the Frankish Emperor Louis the Pious.[85] Due to the sudden death of Krum on 14 April 814, however, the campaign was never launched.[83] Khan Krum implemented legal reforms and issued the first known written law code of Bulgaria that established equal rules for all peoples living within the country's boundaries, intending to reduce poverty and to strengthen the social ties in his vastly enlarged state.[86][87]

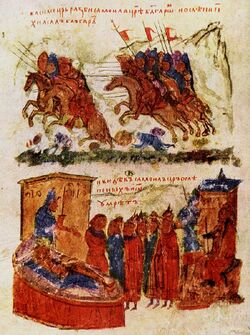

Krum's successor Khan Omurtag (r. 814–831) concluded a 30-year peace treaty with the Byzantines, thus allowing both countries to restore their economies and finance after the bloody conflicts in the first decade of the century, establishing the border along the Erkesia trench between Debeltos on the Black Sea and the valley of the Maritsa River at Kalugerovo.[88][89] To the west the Bulgarians were in control of Belgrade (whose modern name was first known as Alba Bulgarica) by the 820s and the northwestern boundaries with the Frankish Empire were firmly settled along the middle Danube by 827.[90][91][12] To the north-east Omurtag fought the Khazars along the Dnieper River, which was the easternmost limit of Bulgaria.[92] Extensive building was undertaken in the capital Pliska, including the construction of a magnificent palace, pagan temples, ruler's residence, fortress, citadel, water-main, and bath, mainly from stone and brick.[91][93] Omurtag started in 814 persecution of Christians,[94] in particular against the Byzantine prisoners of war settled north of the Danube. Menologion of Basil II, glorifies Basil as a warrior defending Orthodox Christendom against the attacks of the pagan Bulgars. The expansion to the south and south-west continued under Omurtag's successors under the guidance of the capable kavhan (First Minister) Isbul. During the short reign of Khan Malamir (r. 831–836), the important city of Philippopolis (Plovdiv) was incorporated into the country. Under Khan Presian (r. 836–852), the Bulgarians took most of Macedonia, and the borders of the country reached the Adriatic Sea near Valona and Aegean Sea.[12] Byzantine historians do not mention any resistance against the Bulgarian expansion in Macedonia, leading to the conclusion that the expansion was largely peaceful. With this, Bulgaria had become the dominant power in the Balkans.[12] The advances further west was blocked by the development of a new Slavic state under Byzantine patronage, the Principality of Serbia.[12] Between 839 and 842 the Bulgarians waged war on the Serbs but did not make any progress. Historian Mark Whittow asserts that the claim for a Serb victory in that war in De Administrando Imperio was wishful Byzantine thinking,[12] but notes that any Serb submission to the Bulgarians went no further than the payment of tribute.[12]

The reign of Boris I (r. 852–889) began with numerous setbacks. For ten years the country fought against the Byzantine Empire, Eastern Francia, Great Moravia, the Croats and the Serbs forming several unsuccessful alliances and changing sides.[95][96] Around August 863 there was a period of 40 days of earthquakes and there was a lean harvest, which caused famine throughout the country. To cap it all, there was an incursion of locusts. Yet, despite all the military setbacks and natural disasters, the skilful diplomacy of Boris I prevented any territorial losses and kept the realm intact.[95] In this complex international situation Christianity had become attractive as a religion by the mid 9th-century because it provided better opportunities for forging reliable alliances and diplomatic ties.[97] Taking this into account, as well as a variety of internal factors, Boris I converted to Christianity in 864, assuming the title Knyaz (Prince).[97] Taking advantage of the struggle between the Papacy in Rome and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, Boris I brilliantly manoeuvred to assert the independence of the newly established Bulgarian Church.[98] To check the possibility of Byzantine interference in the internal matters of Bulgaria, he sponsored the disciples of the brothers Cyril and Methodius to create literature in Old Bulgarian language.[99] Boris I dealt ruthlessly with the opposition to the Christianisation of Bulgaria, crushing a revolt of the nobility in 866 and overthrowing his own son Vladimir (r. 889–893)[a] after he attempted to restore the traditional religion.[100] In 893 he convened the Council of Preslav where it was decided that the capital of Bulgaria was to be moved from Pliska to Preslav, the Byzantine clergy was to be banished from the country and replaced with Bulgarian clerics, and Old Bulgarian language was to replace the Greek in liturgy.[101] Bulgaria was to become the principal threat to the stability and security of the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century.[102]

Golden Age

The decisions of the Council of Preslav brought an end to the Byzantine hopes to exert influence over the newly Christianized country.[103][104] In 894 the Byzantines moved the Bulgarian market from Constantinople to Thessaloniki, affecting the commercial interests of Bulgaria and the principle of Byzantine–Bulgarian trade, regulated under the Treaty of 716 and later agreements on the most favoured nation basis.[105][106][107] The new Prince, Simeon I (r. 893–927), who came to be known as Simeon the Great, declared war and defeated the Byzantine army in Thrace.[108][109] The Byzantines turned for aid to the Magyars, who at the time inhabited the steppes to the north-east of Bulgaria. The Magyars scored two victories over the Bulgarians and pillaged Dobrudzha but Simeon I allied with the Pechenegs further east and in 895 the Bulgarian army inflicted a crushing defeat on the Magyars in the steppes along the Southern Bug River. At the same time, the Pechenegs advanced westwards and prevented the Magyars from returning to their homeland.[110] The blow was so heavy that the Magyars were forced to migrate west, eventually settling in the Pannonian Basin, where they eventually established the Kingdom of Hungary.[111][110] In 896 the Byzantines were routed in the decisive battle of Boulgarophygon and pleaded for peace that confirmed the Bulgarian domination of the Balkans,[112] restored the status of Bulgaria as a most favoured nation, abolished the commercial restrictions and obliged the Byzantine Empire to pay annual tribute.[113][114] The peace treaty remained in force until 912 although Simeon I did violate it following the sack of Thessaloniki in 904, extracting further territorial concessions in Macedonia.[115]

In 913 the Byzantine emperor Alexander provoked a bitter war after resolving to discontinue paying an annual tribute to Bulgaria.[116] However, the military and ideological initiative was held by Simeon I, who was seeking casus belli to fulfil his ambition to be recognized as Emperor (in Bulgarian, Tsar) and to conquer Constantinople, creating a joint Bulgarian–Roman state.[117] In 917, the Bulgarian army dealt a crushing defeat to the Byzantines at the battle of Achelous, resulting in Bulgaria's total military supremacy in the Balkans.[118][119] In the words of Theophanes Continuatus "a bloodshed occurred, that had not happened in centuries",[120] and Leo the Deacon witnessed piles of bones of perished soldiers on the battlefield 50 years later.[121] The Bulgarians built on their success with further victories at Katasyrtai in 917, Pegae in 921 and Constantinople in 922. The Bulgarians also captured the important city of Adrianople in Thrace and seized the capital of the Theme of Hellas, Thebes, deep in southern Greece.[122][123] Following the disaster at Achelous, Byzantine diplomacy incited the Principality of Serbia to attack Bulgaria from the west, but this assault was easily contained. In 924, the Serbs ambushed and defeated a small Bulgarian army,[124] provoking a major retaliatory campaign that ended with Bulgaria's annexation of Serbia at the end of that year.[125][126] Further expansion in the Western Balkans was checked by King Tomislav of Croatia, who was a Byzantine ally and defeated a Bulgarian invasion in 926.[127][128] Simeon I was aware that he needed naval support to conquer Constantinople and in 922 sent envoys to the Fatimid caliph Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah in Mahdia to negotiate the assistance of the powerful Arab navy. The caliph sent representatives to Bulgaria to arrange an alliance but his emissaries were captured en route by the Byzantines near the Calabrian coast. The Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos managed to avert a Bulgarian–Arab alliance by showering the Arabs with generous gifts.[129][130] The war dragged on until Simeon I's death in May 927. By then Bulgaria controlled almost all Byzantine possessions in the Balkans, but without a fleet did not attempt to storm Constantinople.[131]

Both countries were exhausted by the huge military efforts that had taken a heavy toll on the population and economy. Simeon's successor Peter I (r. 927–969) negotiated a favourable peace treaty. The Byzantines agreed to recognize him as Emperor of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as an independent Patriarchate, as well as to pay an annual tribute.[132][133][134] The peace was reinforced with a marriage between Peter and Romanos's granddaughter Irene Lekapene.[133][135] This agreement ushered in a period of 40 years of peaceful relations between the two powers. During the first years of his reign, Peter I faced revolts by two of his three brothers, John in 928 and Michael in 930, but both were quelled.[136] During most of his subsequent rule until 965, Peter I presided over a Golden Age of the Bulgarian state in a period of political consolidation, economic expansion and cultural activity.[137][138]

Decline and fall

Despite the treaty and the largely peaceful era that followed, the strategic position of the Bulgarian Empire remained difficult. The country was surrounded by aggressive neighbours – the Magyars to the north-west, the Pechenegs and the growing power of Kievan Rus' to the north-east, and the Byzantine Empire to the south, which proved to be an unreliable neighbour.[139] Bulgaria suffered several devastating Magyar raids between 934 and 965. The growing insecurity, as well as expanding influence of the landed nobility and the higher clergy at the expense of the personal privileges of the peasantry, led to the emergence of Bogomilism, a dualistic heretic sect that in the subsequent centuries spread to the Byzantine Empire, northern Italy and southern France (cf. Cathars).[140] To the south, the Byzantine Empire reversed the course of the Byzantine–Arab wars against the declining Abbasid Caliphate and in 965 discontinued the payment of the tribute, leading to sharp deterioration in their relations.[141] In 968 the Byzantines incited Kievan Rus' to invade Bulgaria. In two years the Kievan Prince Svyatoslav I defeated the Bulgarian army, captured Preslav and established his capital at the important Bulgarian city of Preslavets (meaning "Little Preslav").[142] In this desperate situation the aging Peter I abdicated, leaving the crown to his son Boris II (r. 969–971), who had little choice but to cooperate with Svyatoslav.[143] The unexpected success of the Rus' campaigns led to a confrontation with the Byzantine Empire.[142] The Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes eventually defeated Svyatoslav's forces and compelled him to leave the Balkans in 971.[144][145] In the course of their campaign the Byzantines seized Preslav and detained Boris II. Initially John I Tzimiskes presented himself as a liberator but Boris II was promptly forced to ritually abdicate in Constantinople.[146] Although at the time the Byzantines controlled only the eastern regions of the country, Bulgaria was proclaimed a Byzantine province.[147]

The lands to the west of the Iskar River remained free and the Bulgarians were able to regroup headed by the four Cometopuli brothers.[148] By 976, the youngest of them, Samuel, concentrated all power in his hands following the death of his elder siblings. When in 976 the rightful heir to the throne, Boris II's brother Roman (r. 971–997), escaped from captivity in Constantinople, he was recognized as Emperor by Samuel,[149][b] who remained the chief commander of the Bulgarian army. Peace was impossible; as a result of the symbolic ending of the Bulgarian Empire following Boris II's abdication, Roman, and later Samuel, were seen as rebels and the Byzantine Emperor was bound to enforce the imperial sovereignty over them.[149] This led to more than 40 years of increasingly bitter warfare.[149] A capable general and good politician, at first Samuel managed to turn the fortunes to the Bulgarians. The new Byzantine Emperor Basil II was decisively defeated in the Battle of the Gates of Trajan in 986 and barely escaped with his life.[150][151] The Byzantine poet John Geometres wrote of the defeat:

Even if the sun would have come down, I would have never thought that the Moesian [Bulgarian] arrows were stronger than the Ausonian [Roman, Byzantine] spears.... And when you, Phaethon [Sun], descend to the earth with your gold-shining chariot, tell the great soul of the Caesar[c]: The Istros [Bulgaria] took the crown of Rome. Take up arms, the arrows of the Moesians broke the spears of the Ausonians.[152]

Immediately after the victory Samuel pushed east and recovered north-eastern Bulgaria, along with the old capitals, Pliska and Preslav. In the next ten years the Bulgarian armies expanded the country south annexing the whole of Thessaly and Epirus and plundering the Peloponnese Peninsula.[153] With the major Bulgarian military successes and the defection of a number of Byzantine officials to the Bulgarians, the prospect of the Byzantines losing all their Balkan themes was quite real.[154] Threatened by an alliance between the Byzantines and the Serbian state of Duklja, in 997 Samuel defeated and captured its Prince Jovan Vladimir and took control of the Serb lands.[155] In 997, following the death of Roman, the last heir of the Krum's dynasty, Samuel was proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria. He established friendly relations with Stephen I of Hungary through a marriage between his son and heir Gavril Radomir and Stephen's daughter but eventually Gavril Radomir expelled his wife and in 1004 Hungary participated with the Byzantine forces against Bulgaria.[156] After 1000 the tides of the war turned in favor of the Byzantines under the personal leadership of Basil II, who launched annual campaigns of methodical conquest of the Bulgarian cities and strongholds that were sometimes carried out in all twelve months of the year instead of the usual short campaigning of the epoch with the troops returning home to winter.[157] In 1001 they seized Pliska and Preslav in the east, in 1003 a major offensive along the Danube resulted in the fall of Vidin after an eight-month siege, and in 1004 Basil II defeated Samuel in the battle of Skopje and took possession of the city.[157] This war of attrition dragged on for a decade until 1014, when the Bulgarians were decisively defeated at Kleidion. Some 14,000 Bulgarians were captured; it is said that 99 out of every 100 men were blinded, with the remaining hundredth man left with one eye so as to lead his compatriots home, earning Basil II the moniker "Bulgaroktonos", the Bulgar Killer.[158] When they arrived in Samuel's residence in Prespa, the Bulgarian Emperor suffered a heart attack at the grisly sight and died two days later, on 6 October.[158] Resistance continued for four more years under Gavril Radomir (r. 1014–1015) and Ivan Vladislav (r. 1015–1018) but after the demise of the latter during the siege of Dyrrhachium the nobility surrendered to Basil II and Bulgaria was annexed by the Byzantine Empire.[159] The Bulgarian aristocracy kept its privileges, although many noblemen were transferred to Asia Minor, thus depriving the Bulgarians of their natural leaders.[160] Although the Bulgarian Patriarchate was demoted to an archbishopric it retained its sees and enjoyed a privileged autonomy.[160][161] Despite several major attempts at restoring its independence, Bulgaria remained under Byzantine rule until the brothers Asen and Peter liberated the country in 1185, establishing the Second Bulgarian Empire.[162]

Government

The First Bulgarian Empire was a hereditary monarchy. The monarch was the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, a judge, and a high priest during the pagan period.[163][164] He guided the external policy of the country and could conclude treaties personally or through authorised emissaries.[164] In the pagan period the title of the ruler was Khan. After 864 Boris I adopted the Slavic Knyaz (Prince), and since 913 the Bulgarian monarchs were recognised as Tsars (Emperors).[165][166] The authority of the Khan was limited by the leading noble families and the People's Council. The People's Council included the nobility and the "armed people" was gathered to discuss issues of crucial importance for the state. A People's Council in 766 dethroned Khan Sabin because he was seeking peace with the Byzantines.[68] According to the old Bulgarian tradition the Khan was first among equals, which was among the reasons why Boris I decided to convert to Christianity, as Christian monarchs ruled by the grace of God.[100] However, the divinity of the Bulgarian ruler, as well as his superiority over the Byzantine Emperor, were already asserted by Khan Omurtag (r. 814–831),[167] as stated in the Chatalar Inscription:

The second most important post in Bulgaria after the monarch was the kavhan, monopolised by the members of the tentatively known "Kavhan family".[169] The kavhan had broad powers and commanded the left wing of the army, and at times the whole army.[170] He could be a co-ruler or a regent during the minority of the monarch;[171][172] the sources mention that Khan Malamir "ruled together with kavhan Isbul" (fl. 820s–830s)[169] and kavhan Dometian is noted as an associate [in the government] of Gavril Radomir (r. 1014–1015).[173] The third highest-ranking official was the ichirgu-boila, who commanded the right wing of the army at war and might have had the role of a foreign minister.[171][174] Under his direct command were 1,300 soldiers.[171] Historian Veselin Beshevliev assumes that the post might have been created under the reign of Khan Krum (r. 803–814), or earlier, in order to limit the power of the kavhan.[175] Although initially the Bulgarians did not have their own writing system, the presence of numerous stone inscriptions, mainly in Greek, indicate the existence of a chancellery to the Khan that was probably organised in the Byzantine manner.[176][177] Part of the chancellery's staff might have been Greeks and even monks, despite the fact that the country was still pagan.[176]

Social classes

According to an inscription dated from the reign of Khan Malamir (r. 831–836) there were three classes in pagan Bulgaria – boilas, bagains and Bulgarians, i.e. the common people.[178] The nobility were initially known as the boila but after the 10th century the word was transformed to bolyar, which was eventually adopted in many countries in Eastern Europe. Each boila clan had its own totem and was believed to had been divinely established, hence their staunch opposition to Christianity, which was seen as a threat to their privileges.[179] Many of the clans had ancient origin that could be traced back to the time when the Bulgars inhabited the steppes to the north and east of the Black Sea.[163] The Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans mentions monarchs of three clans that ruled Bulgaria until 766 – Dulo, Vokil and Ugain.[163] The power of the principal noble families was greatly crippled in the aftermath of the anti-Christian rebellion of 866, when Boris I executed 52 leading boilas along with their families.[180]

The boila were divided into inner and outer boilas and it was among their ranks that the holders of the highest military and administrative posts were selected.[178][181] Most likely the outer boilas resided outside the capital, while the inner ones were member of the court under the direct influence of the monarch.[182]

The bagains were the second-ranking aristocratic class and were divided into numerous sub-ranks.[183] The presence of two separate classes of nobility is further confirmed in the Responsa Nicolai ad consulta Bulgarorum (Responses of Pope Nicholas I to the Questions of the Bulgarians), where Boris I wrote about primates and mediocres seu minores.[181] Another privileged group were the tarkhans, although from the surviving inscriptions it is impossible to determine whether they belonged to the boilas or to the bagains, or were a separate class.[184] The original Bulgar titles and many of the institutions from the pagan era were preserved after the Christianisation of Bulgaria until the very fall of the First Empire.[185] The beginning of the 9th century was marked with a process of incorporation of both Slavs and Byzantine Greeks in the ranks of the Bulgarian nobility and privileged classes, which increased the power of the monarch that had been previously curtailed by the leading Bulgar aristocratic families.[186][187] Since that time certain Slavic titles became more prominent, such as župan, and some of them mingled forming titles like župan tarkhan.[188]

The peasants lived in rural communities known as zadruga and had collective responsibility.[189] The majority of the peasantry were personally free under the direct rule of the central administration and the legislation introduced following the adoption of Christianity regulated their relations.[189] The number of personally dependent peasants bound to nobility or ecclesiastical estates increased since the 10th century.[190]

Administration

Due to the limited remaining sources it is very difficult to reconstruct the administrative evolution and division of the country. Initially the Slavic tribes retained their autonomy but since the beginning of the 9th century commenced a process of centralisation.[177][191] As Bulgaria's territory steadily expanded, measures against tribal autonomy were deemed necessary in order to achieve more effective control and to prevent separatism.[192] When in the 820s some Slavic tribes in western Bulgaria, the Timochani, Branichevtsi and Abodriti sought overlordship from the Franks, Khan Omurtag replaced their chieftains with his own governors.[192] The country was divided into comitati, governed by a comita, although this term was used by Western European chroniclers, who wrote in Latin. It is likely that the Bulgarians used the term земя (zemya, meaning "land"), as mentioned in the Court Law for the People.[193] Their number is unknown, but the Archbishop of Reims Hincmar mentioned that the 866 rebellion against Boris I was headed by the nobility of the 10 comitati.[193][194][195] They were further divided into župi, that in turn consisted of zadrugi. The comita was appointed by the monarch, and was assisted by a tarkhan. The former had many civil and administrative functions, while the latter was responsible for military affairs.[196][197] One of the few comitati known by name was Kutmichevitsa in south-western Bulgaria, corresponding to modern western Macedonia, southern Albania and north-western Greece.[196]

Legislation

The first known written Bulgarian law code was issued by Khan Krum at a People's Council in the very beginning of the 9th century but the text has not survived in its entirety and only certain items have been preserved in the 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia Suda.[87] It prescribed the death penalty for false oaths and accusations and severe penalties for thieves and those who gave them shelter.[87][198][86] The Suda also mentioned that the laws foresaw the uprooting of all vineyards as a measure against drunkenness but this claim is refuted in the contemporary sources, which indicate that, after capturing Pliska in 811, the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I found large quantities of wine, and after the final Bulgarian victory Krum drank wine in the Emperor's skull.[198][199] Krum's legal code is seen by many historians as an attempt to centralise the state and to homogenize society by putting the different elements under a single code of laws.[200] However, since the text is not preserved its precise aims remain unknown.[87]

After the conversion to Christianity Boris I was concerned with the legal matters and asked Pope Nicholas I to provide legal texts.[201] Eventually, the Законъ соудный людьмъ (Zakon sudnyi ljud'm, Court Law for the People), was compiled, based heavily on the Byzantine Ecloga and Nomocanon, but adapted to Bulgarian conditions and valid for the whole population of the country.[202][201] It combined elements of civil, criminal, canon and military law, as well as public and private law, and included substantive norms and procedural guidelines. The Court Law for the People dealt with combating paganism, testimony of witnesses, sexual morality, marital relations, distribution of war booty, etc.[201] To eradicate the residual paganism the law provided that a village that allowed performance of pagan rituals should be transferred in its entirety to the Church, and, should a rich landowner perform them, his lands were to be sold, and the revenue shared among the poor.[189]

Military

After the formation of the Bulgarian state the ruling elite harboured deep distrust towards the Byzantines, against whose perfidy and sudden attacks they had to maintain constant vigilance[45] in all directions. The Byzantine Empire never relinquished its claim over all lands to the south of the Danube and made several attempts to enforce that claim. Throughout the existence of the First Empire Bulgaria could expect Byzantine onslaughts aimed at its destruction.[97] The steppes to the north-east were home to numerous peoples whose unpredictable pillaging raids were also of concern.[203] Therefore, military preparedness was a top priority.[203] Guards always stood on the alert and if anyone was to flee during a watch, the responsible guards are killed without hesitation.[203] Before battle, a "most faithful and prudent man" was sent to inspect all the arms, horses, and materiel, and being ill-prepared or readied in a useless fashion was punishable by death.[203] Capital punishment was also prescribed for riding war horses in peacetime.[204]

The Bulgarian army was armed with various types of weapons, the most widely used being sabres, swords, battle axes, spears, pikes, daggers, arkans, and bows and arrows.[205] The soldiers were often trained to use both spears and bows.[205] The Bulgarians wore helms, mail armor and shields for defence. The helms were usually cone-shaped, while the shields were round and light. The armor was of two types – wedge riveted mail consisting of small metal rings linked together, and scale armour consisting of small armour plates attached to each other.[205] Belts were very important for the early Bulgarians and were often decorated with golden, silver, bronze or copper buckles that reflected the illustrious origin of the holder.[205]

The most important part of the army was the heavy cavalry. In the early 9th century the Bulgarian Khan could muster 30,000 riders "all covered in iron"[206] who were armoured with iron helms and chainmail.[207] The horses too were covered with armour.[208] As the capital, Pliska, was situated in an open plain, the cavalry was essential for its protection.[209] The fortification system of the inner regions of the country was reinforced with several fortified trenches covering huge spaces and supporting the manoeuvrability of the cavalry.[209]

The army was well versed in the use of stratagems. A strong cavalry unit was often held in reserve and would attack the enemy at an opportune moment. Free horses would be sometimes concentrated behind the battle formation to avoid surprise attacks from the rear.[210] The Bulgarian army used ambushes and feigned retreats, during which the cavalrymen rode with their backs to the horse, firing clouds of arrows on the enemy. If the enemy pursued disorganized, they would turn back and fiercely attack them.[210] In 918 the Bulgarians took the capital of the Byzantine theme Hellas Thebes without bloodshed after sending five men with axes into the city, who eliminated the guards, broke the hinges of the gates, and opened them to the main forces.[211][212] The Bulgarians were also able to fight at night – e.g., their victory over the Byzantines in the battle of Katasyrtai.[213][214]

The Bulgarian army was well equipped with siege engines. The Bulgarians employed the services of Byzantine and Arab captives and fugitives to produce siege equipment, such as the engineer Eumathius, who sought refuge with Khan Krum after the capture of Serdica in 809.[208] The 9th century anonymous Byzantine chronicler known as Scrptor incertus lists the contemporary machinery produced and used by the Bulgarians.[215] These included catapults; scorpions; multi-storey siege towers with a battering ram on the bottom floor; testudos – battering rams with metal plating on the top; τρίβόλοι – iron tridents placed hidden amidst the battlefield to hinder the enemy cavalry; ladders, etc.[208] Iron-plated wagons were used for transportation. It is known that Khan Krum prepared 5,000 such wagons for his intended siege of Constantinople in 814.[208] Wooden pontoon bridges were also constructed for crossing rivers.[206][207]

Economy and urbanism

Agriculture was the most important sector of the economy, the development of which was facilitated by the fertile soils of Moesia, Thrace, and partly, Macedonia.[216] The land was divided into "lord's lands" and "village lands".[189] The most widespread cereals were wheat, rye and millet, all of which were staple foods for the populace.[216] Grapes were also significant, especially after the 9th century. Linen was used for fabrics and cloths that were exported to the Byzantine Empire.[216] Harvests were prone to natural calamities, such as droughts or locusts, and there were occasional hunger years. In response to this problem the state maintained reserves of cereals.[217] Animal husbandry was well developed, the main stocks being cattle, oxen, buffalos, sheep, pigs and horses.[217] Animal stocks were vital for farming, transport, military, clothing and food. The importance of the meat for the Bulgarian table was demonstrated in the Responses of Pope Nicholas I to the Questions of the Bulgarians, where seven out of 115 questions concerned meat consumption.[217]

Small-scale mining was developed in the Balkan Mountains, the Rhodope Mountains and some regions of Macedonia.[217] A number of diverse handicrafts thrived in the urban centres and some villages. Preslav had workshops that processed metals (especially gold and silver), stone and wood, and produced ceramics, glass and jewellery.[218][219] The Bulgarians produced higher-quality tiles than the Byzantines and exported them to the Byzantine Empire and Kievan Rus'.[219] There was large-scale production of bricks in eastern Bulgaria, many of them marked with the symbol "IYI", which is associated with the Bulgarian state, indicating possible state-organised production facilities.[218] After the destruction of the Avar Khaganate in the beginning of the 9th century, Bulgaria controlled the salt mines in Transylvania until they were overrun by the Magyars a century later.[220] The importance of the salt trade was illustrated during the negotiations for alliance between Bulgaria and East Francia in 892 when the Frankish King Arnulf demanded that Bulgaria discontinue the export of salt to Great Moravia.[221]

Trade was particularly important to the economy, as Bulgaria lay between the Byzantine Empire, Central Europe, the Rus' and the steppes.[222] Trade relations with the Byzantine Empire were regulated on a most favoured nation basis by treaties that included commercial clauses.[105] The first such treaty was signed in 716 and provided that goods could only be imported or exported when embossed with a state seal. Goods without documents were to be confiscated for the state treasury. The Bulgarian merchants had a colony in Constantinople and paid favourable taxes.[105] The relevance of international trade for Bulgaria was evident, as the country was willing to go to war with the Byzantine Empire when, in 894, the latter moved the market of the Bulgarian traders from Constantinople to Thessaloniki, where they had to pay higher taxes and did not have direct access to goods from the east.[105] In 896 Bulgaria won the war, restoring its status as a most favoured nation and lifting the commercial restrictions.[110] Some Bulgarian towns were very prosperous—e.g., Preslavets on the Danube, described in the 960s as more prosperous than the capital of the Rus', Kiev.[222] A contemporary chronicle lists the main trade partners and chief imports to Bulgaria. The country imported gold, silks, wine and fruits from the Byzantine Empire, silver and horses from Hungary and Bohemia, furs, honey, wax and slaves from the Rus'.[223] There were commercial ties with Italy and the Middle East as well.[224]

The First Bulgarian Empire did not mint coins, and taxes were paid in kind.[225][226] It is not known whether they were based on land or on person, or both. In addition to the taxes the peasantry must have had other obligations, such as building and maintaining infrastructure and defences, as well as providing food and materiel to the army.[226][227] The Arab writer Al-Masudi noted that instead of money the Bulgarians used cows and sheep to buy goods.[225]

The density of the network of towns was high. The economic historian Paul Bairoch estimated that in 800 Pliska had 30,000 inhabitants and, by c. 950, Preslav had some 60,000, making it the largest city in non-Muslim Europe, save Constantinople.[228] In comparison, the largest cities in contemporary France and Italy did not reach 30,000 and 50,000 respectively.[228] Alongside the two capitals existed other prominent urban centres, making Bulgaria the most urbanised region in Christian Europe at the time along with Italy.[228] According to contemporary chronicles there were 80 towns in the region of the lower Danube alone.[229] Surviving sources list more than 100 settlements in the western part of the Empire, where the Bulgarian Orthodox Church possessed properties.[230] The larger urban centres consisted of an inner and an outer town. The inner town would be encircled with stone walls and had administrative and defence functions, while the outer town, usually unprotected, was the centre of economic activities with markets, workshops, vineyards, gardens and dwellings for the populace.[231] However, as elsewhere in the Early Middle Ages, the country remained predominantly rural.

Religion

Pagan Bulgaria

For almost two centuries after its creation, the Bulgarian state remained pagan. The Bulgars and the Slavs continued to practice their indigenous religions. The Bulgar religion was monotheistic, linked to the cult to Tangra, the God of the Sky.[232][233] The worship of Tangra is proven by an inscription that reads "Kanasubigi Omurtag, a divine ruler... performed sacrifice to God Tangra".[234] The ruling Khan had an important place in the religious life: he was the high priest and performed rituals.[163] A large sanctuary dedicated to the cult of Tangra existed near the modern village of Madara.[232] The Bulgars practised shamanism, believed in magic and charms, and performed various rituals.[232] Some of the rituals were described by the Byzantines after the "most Christian" ruler Leo V had to pour out water on the ground from a cup, personally turn round horse saddles, touch triple bridle, lift grass high above the ground and cut up dogs as witnesses during the ceremony of the signing of the Byzantine–Bulgarian Treaty of 815.[235] The pouring of water was a reminder that if the oath is broken, blood would pour out. In the same sense can be explained the turning of the saddle – a warning that the violator would not be able to ride or would fall dead from his horse during battle. The triple bridle symbolised the toughness of the agreement and the lifting of grass reminded that no grass would remain in the enemy country if the peace was broken. The sacrifice of dogs was a common custom among the Turkic peoples which further strengthened the treaty.[235]

The Slavs worshiped numerous deities. The supreme god was Perun, the god of thunder and lightning.[236] Perun was the only god mentioned (though not by name) by the first authoritative reference to the Slavic mythology in written history, the 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius, who described the Slavs that settled south of the Danube. Procopius noted that they also worshipped rivers and believed in nymphs.[236] A number of mythological beings from the Slavic pantheon have persisted in Bulgarian folklore to the present, such as samodivas, halas, vilas, rusalkas, slavic dragons, etc. During sacrifices the Slavs would perform divinations. After the adoption of Christianity the worship of Perun merged with the cult of Saint Elijah.[236]

Christianity was practised in Bulgaria throughout the whole pagan period. Its dissemination among the populace increased as a result of the successful wars of Khan Krum in the beginning of the 9th century.[237] Krum employed many Byzantine Christians – Greeks, Armenians and Slavs – in his military and administration; some of them served as deputies of the kavhan and the ichirgu-boila.[238] Tens of thousands Byzantines were resettled across Bulgaria, mainly beyond the Danube River to protect the north-eastern borders, so that they could face non-Byzantines.[239] Many of them, however, maintained clandestine links with the Byzantine court which fuelled the traditional distrust of the Bulgarian elite and resulted in a large-scale persecution of Christianity under the Khans Omurtag and Malamir. Omurtag and the nobility saw the Christians as Byzantine agents and felt that this religion, with its hierarchy based in Byzantium, was a threat to Bulgarian independence.[179] There were some executions, including two of the five strategoi who served under Krum, Leo and John, the metropolitan of Adrianople, the bishop of Debeltos, etc.[179][240] The list of the martyred Christians included Bulgar (Asfer, Kuberg) and Slav names.[240] The dismissive attitude of the Christians towards the pagans was insulting to the Bulgarian elite. In a conversation with a Byzantine Christian, Omurtag told him: "Do not humiliate our gods, for their power is great. As a proof, we who worship them, have conquered the whole Roman state".[241] Yet, despite all measures, Christianity continued to spread,[179] reaching the members of the Khan's own family. Omurtag's eldest son Enravota, seen as pro-Christian, was disinherited and eventually converted to Christianity. After refusing to renounce his faith, he was executed by orders of his brother Malamir c. 833 and became the first Bulgarian saint.[242] The attitude of the Bulgarian rulers to Christianity is seen in the Philippi Inscription of Khan Presian:

...If someone seeks the truth, God watches. And if one lies, God watches. The Bulgarians did many good things to the Christians [the Byzantines] and the Christians forgot, but God watches.[243]

Christianization

By 863 Presian's successor Khan Boris I had decided to accept Christianity.[244] The sources do not mention the reasons behind this decision but there were several political rationales that he had considered. As Christianity was spreading further into Europe in the 9th century the pagan countries found themselves encircled by Christian powers which could use religion as an acceptable excuse for aggression.[97] Conversion, on the other hand, would establish the country as an equal international partner.[97] There is evidence that Bulgaria had contacts with the Muslim world as well – either directly or through Volga Bulgaria, which had adopted Islam at about the same time – but Bulgaria was too far away from any Muslim country that could be of political benefit, and a large part of the population had already converted to Christianity.[245] Furthermore, the Christian doctrine would cement the monarch's position high above the nobility as an autocrat, being ruler "by the grace of God" and God's representative on Earth.[246][247] Moreover, Christianity presented excellent opportunity to firmly consolidate both Bulgars and Slavs as a single Bulgarian people under a common religion.[247]

In 863 Boris I sought a mission from East Francia rather than from the Byzantine Empire. He had an alliance with the Eastern Franks since 860 and was aware that the larger distance between the two countries was an obstacle for them to yield direct influence on the future Bulgarian Church.[247] He was fully aware that as a neighbour Byzantium would try to interfere with Bulgarian matters.[247] Indeed, the Byzantine Empire was determined to place the Bulgarian Church under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople because it hoped it could serve as leverage to influence Bulgarian policies, and to prevent Bulgaria from becoming a military tool of the Papacy to enforce the Pope's wishes on the Empire.[248] Upon learning about Boris I's intentions the Byzantine Emperor Michael III invaded Bulgaria. At the time the Bulgarian army was engaged in warfare against Great Moravia to the north-east and Boris I agreed to negotiate.[233][247] The Byzantines' only demand was that Boris I adopt Orthodox Christianity and to accept Byzantine clergy to evangelise the population.[247] Boris I conceded and was baptised in 864, taking the name of his godfather, Emperor Michael.[233][249]

The highest posts in the newly established Bulgarian Church were held by Byzantines who preached in Greek. Aware of the dangers that the spiritual dependency on the Byzantine Empire could pose for Bulgaria's independence, Boris I was determined to ensure the autonomy of the Bulgarian Church under a Patriarch.[180] Since the Byzantines were reluctant to grant any concessions Boris I took advantage on the ongoing rivalry between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Papacy in Rome in order to prevent either of them from exerting religious influence on his lands.[180][98] In 866 he sent a delegation to Rome under the high-ranking official Peter declaring his desire to accept Christianity in accordance with the Western rites along with 115 questions to Pope Nicholas I. The Pope's detailed answers to Boris I's questions were delivered by two bishops heading a mission to facilitate the conversion of the Bulgarian people.[250] However, neither Nicolas I nor his successor Adrian II agreed to recognize an autonomous Bulgarian Church, which cooled the relations between the two sides.[251] Bulgaria's shift towards Rome on the other hand, made the Byzantines much more conciliatory. In 870, at the Fourth Council of Constantinople, the Bulgarian Church was recognized as an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church under the supreme direction of the Patriarch of Constantinople.[252][253]

The adoption of Christianity was met with opposition by large numbers of the nobility. In 866 Boris I faced a major rebellion of the boila from all parts of the country. The insurgency was crushed and 52 leading boilas were executed along with their whole kin.[100][254] After Boris I abdicated in 889 his successor and eldest son Vladimir (r. 889–893) attempted to restore paganism but his father took arms against him and had him deposed and blinded.[100]

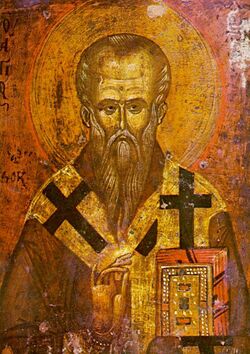

Bulgarian Orthodox Church

Around 870 the Bulgarian Church became an autonomous archbishopric.[253] The decree of autonomy under the nominal ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Constantinople was far greater than could possibly have been achieved under the Papacy.[252] Following the Fourth Council of Constantinople the Byzantine clergy was re-admitted to Bulgaria and allowed to preach in Greek.[252] However, as a result of the Council of Preslav in 893 Old Bulgarian was declared the official language of the state and the Church and the Greek-speaking Byzantine priests once again had to leave the country. Thus, from that point, the church was entirely staffed by Bulgarians.[255]

Boris I's successor Simeon I was not content to leave the Bulgarian Church as an archbishopric and was determined to raise it to a patriarchate, in light of his own ambition to become an emperor. He was well acquainted with the Byzantine imperial tradition that the autocrat must have a patriarch and there could be no empire without one.[256] In the aftermath of his remarkable triumph over the Byzantines in the battle of Achelous, in 918 he convened a council and elevated Archbishop Leontius to patriarch.[256] The decisions of that council were not recognized by the Byzantines[257] but as a result of the Bulgarian victory in the war they eventually recognized Leontius' successor Demetrius as Patriarch of Bulgaria in 927.[258] It was the first Patriarchate officially accepted, apart from the ancient Pentarchy. It is likely that the seat of the Patriarchate was in the city of Drastar on the Danube River rather than in the capital Preslav.[259] In the late 10th century the Bulgarian Patriarchate included the following dioceses: Ohrid, Kostur, Glavinitsa (in modern southern Albania), Maglen, Pelagonia, Strumitsa, Morovizd (in modern northern Greece), Velbazhd, Serdica, Braničevo, Niš, Belgrade, Srem, Skopje, Prizren, Lipljan, Servia, Drastar, Voden, Ras, Chernik, Himara, Drinopol, Butrint, Yanina, Petra and Stag.[230][260]

After the fall of the eastern parts of the empire under Byzantine occupation in 971 the seat of the Patriarchate was relocated to Ohrid in the west.[149][261] With the final conquest of Bulgaria in 1018 the Patriarchate was demoted to an archbishopric but retained many privileges. It kept control of all existing episcopal sees, the seat remained in Ohrid and its titular, the Bulgarian John of Debar, kept his office. Furthermore, the Bulgarian archbishopric was given a special position – it was placed directly under the emperor rather than under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.[160][161]

Monasticism grew steadily and the monasteries quickly became major landowners with a large population of peasants living on their estates.[262] It developed further under the reign of Emperor Peter I, accompanied by the augmentation of their properties.[222] Many high-ranking nobles and members of the ruling family tonsured and died as monks, including Boris I, his brother Doks, Peter I, the ichirgu-boila Mostich, etc.[263] The growing opulence of monastic life led to an increase of asceticism among more pious monks. One of them, John of Rila, became a hermit in the Rila Mountains and his virtues soon attracted a number of followers,[222] who founded the renowned Rila Monastery after his death. He preached about living in harmony and stressed the value of manual labour and the need the monks never to aspire to riches and power.[222][264] John of Rila was revered as a saint while he was still alive and eventually became patron of the Bulgarian people.

In the 10th century Bulgarian clerics established connections with the emerging Christian communities in the Rus'.[265] Bulgaria seems to had been an established centre from where the small number of Ruthenian Christians obtained clergy and liturgical texts.[147] As a result of the Sviatoslav's invasion of Bulgaria many of his soldiers were influenced by Christianity and maintained that interest after their return. The connections between Bulgarians and Ruthenians must be considered an important background to the official conversion to Christianity of Kievan Rus' in 988.[147]

Bogomilism

During the reign of Emperor Peter I (r. 927–969) a heretical movement known as Bogomilism arose in Bulgaria. The heresy was named after its founder the priest Bogomil whose name can be translated as dear (mil) to God (Bog). The main sources about Bogomilism in Bulgaria come from a letter of the Ecumenical Patriarch Theophylact of Constantinople to Peter I (c. 940), a treatise by Cosmas the Priest (c. 970) and the anti-Bogomil council of Emperor Boril of Bulgaria (1211).[266] Bogomilism was a neo-Gnostic and dualist sect that believed that God had two sons, Jesus Christ and Satan, that represented the two principles good and evil.[267] God had created light and the invisible world, while Satan rebelled and created darkness, the material world and man.[267][268] Therefore, they rejected marriage, reproduction, the Church, the Old Testament, the Cross, etc.[269] The Bogomils were divided into several categories, led by the perfecti (the perfect ones) that never married, consumed no meat and wine and preached the gospel. Women too could become perfecti.[270] The other two categories were the believers, who had to adopt and follow most of the Bogomil moral ethics, and the listeners, who were not required to change their lifestyle.[271] The Bogomils were described by Cosmas as looking docile, modest and silent from the outside, but being hypocrites and ravenous wolves in the inside.[268][269] The Bulgarian Orthodox Church condemned the teachings of Bogomilism. Members of the sect were persecuted by the state authorities as well; the Bogomils preached civil disobedience because they considered the state—as with anything earthly—to be linked with Satan.[268] The sect could not be eradicated and from Bulgaria it eventually spread to the rest of the Balkans, the Byzantine Empire, southern France and northern Italy. In certain regions of Western Europe the heresy flourished under different names – Cathars, Albigensians, Patarins – until the 14th century.[267][268]

Formation of Bulgarian nationality

The Bulgarian state existed before the formation of the Bulgarian people.[201] Prior to the establishment of the Bulgarian state the Slavs had mingled with the native Thracian population.[272] The population and the density of the settlements increased after 681 and the differences among the individual Slavic tribes gradually disappeared as communications became regular among the regions of the country.[273] By the second half of the 9th century, Bulgars and Slavs, and romanized or hellenized Thracians had lived together for almost two centuries and the numerous Slavs were well on the way to assimilating the Thracians and the Bulgars.[274][275] Many Bulgars had already started to use the Slavic Old Bulgarian language while the Bulgar language of the ruling caste gradually died out leaving only certain words and phrases.[276][277][55] The Christianization of Bulgaria, the establishment of Old Bulgarian as a language of the state and the Church under Boris I, and the creation of the Cyrillic Script in the country, were the main means to the final formation of the Bulgarian Nation in the 9th century; this included Macedonia, where the Bulgarian khan, Kuber, established a Bulgar state existing in parallel with Khan Asparukh's Bulgarian Empire.[278][99][279] The new religion dealt a crushing blow to the privileges of the old Bulgar aristocracy; also, by that time, many Bulgars were presumably speaking Slavic.[275] Boris I made it a national policy to use the doctrine of Christianity, that had neither Slavic or Bulgar origin, to bind them together in a single culture.[280] As a result, by the end of the 9th century the Bulgarians had become a single Slavic nationality with ethnic awareness that was to survive in triumph and tragedy to present.[201]

Culture

The cultural heritage of the First Bulgarian Empire is usually defined in Bulgarian historiography as the Pliska-Preslav culture, named after the first two capitals, Pliska and Preslav, where most of the surviving monuments are concentrated. Many monuments of that period have been found around Madara, Shumen, Novi Pazar, the village of Han Krum in north-eastern Bulgaria, and in the territory of modern Romania, where Romanian archaeologists called it the "Dridu culture".[281] Remains left by the First Empire have also been discovered in southern Bessarabia, now divided between Ukraine and Moldova, as well as in the modern Republic of Macedonia, Albania and Greece.[139][282] A treatise of the 10th-century Bulgarian cleric and writer Cosmas the Priest describes a wealthy, book-owning and monastery-building Bulgarian elite, and the preserved material evidence suggests a prosperous and settled picture of Bulgaria.[137][139]

Architecture

Civil architecture

The first capital, Pliska, initially resembled a huge encampment spanning an area of 23 km2 with the eastern and western sides measuring some 7 km in length, the northern, 3.9 km, and the southern, 2.7 km. The whole area was encircled by a trench 3.5 m wide in the foundation and 12 m wide in the upper part and earthen escarpment with similar proportions – 12 m wide in the foundation and 3.5 m in the upper part.[283] The inner town measured 740 m to the north and to the south, 788 m to the west, and 612 m to the east. It was protected by stone walls 10 m high and 2.6 m thick, constructed with large carved blocks.[283] There were four gates, each protected by two pairs of quadrangular towers. The corners were protected by cylindrical towers and there were pentagonal towers between each corner and gate tower.[283] The inner town harboured the Khan's palace, the temples, and the noble residences. The palace complex included baths, a pool and a heating system.[284] There were several inns, as well as numerous shops and workshops.[285]

The Bulgarians also constructed forts with residences, called auls, or fortified palaces, by contemporary Byzantine authors.[285] An example of this type of construction is the Aul of Omurtag, mentioned in the Chatalar Inscription, which bears many similarities to Pliska, such as the presence of baths and the usage of monumental construction techniques with large carved limestone blocks.[286] Archaeologists have discovered a damaged lion statue that was originally 1 m in height and matches this description from an inscription: "In the field of Pliska staying he [Omurtag] made a court/camp (aulis) at [the river] Ticha... and skillfully erected a bridge at Ticha together with the camp [he put] four columns and above the columns he erected two lions."[286] The same method of construction was employed in a fortress on the Danubian island of Păcuiul lui Soare (in modern Romania), where the gate is similar in plan to those at Pliska, Preslav and the Aul of Omurtag.[286] The fortress of Slon, an important juncture that connected the salt mines of Transylvania with the lands to the south of the Danube, and constructed in the same manner, was located further north, on the southern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains.[281]

The second capital, Preslav, covered an area of 5 km2 in the shape of irregular pentagon and, like Pliska, was divided into an inner and an outer town.[287] The city experienced an extensive construction programme under Simeon I who intended it to rival Constantinople. The inner town contained two palaces, referred to by archaeologists as the Western Palace and the Throne Hall, that were linked.[287] Very few elements of the decoration have survived – marble plates and two monolithic columns of green marble that probably enclosed the arch above the throne.[288] The whole complex was larger than the Pliska Palace and was walled with the bath adjoining the southern wall.[289] A ceremonial road covered with stone plates linked the northern gate and the palace complex and formed a spacious plaza in front of it.[290] The outer town housed estates, churches, monasteries, workshops and dwellings.[289] Adjoined to the outer side of southern gates of the inner town there was a large trading edifice with 18 rooms for commerce on the first floor and accommodation rooms on the second.[224] The most common plan of the commercial, artesian and residential monastic edifices was rectangular with the first floor being used for production, and the second one – for living. Some of the buildings had marble or ceramic tile floors, and others had verandas on the second floor.[224] There were two types of plumbing – made of masonry or of clay pipes that brought water from the mountains to the city.[290]

Sacral architecture

After the adoption of Christianity in 864, intensive construction of churches and monasteries began throughout the Empire. Many of them were erected over the old pagan temples.[291] The new sacral architecture altered the appearance of the cities and fortresses.[292] This construction was funded not only by the state but also through donations by the wealthy, known as ktitors.[292] Among the first places of worship to be constructed after 864 was the Great Basilica of Pliska. It was one of the biggest structures of the time, as well as contemporary Europe's longest church, with a rectangular shape reaching 99 m in length.[293][294] The basilica was divided into two almost equal parts – a spacious atrium and the main building.[293]

During the reign of Simeon I the domed cruciform type of church building was introduced and came to dominate the country's sacral architecture.[290] Preslav was adorned with tens of churches and at least eight monasteries. The churches were decorated with ceramics, plastic elements and a variety of decorative forms.[295] The leading example of the city's ecclesiastic architecture is the splendid Round Church. It was a domed rotunda with a two-tiered colonnade in the interior and a walled atrium with niches and columns.[296][297] The style of the church had been influenced by Armenian, Byzantine and Carolingian architecture.[297] There were also a number of cave monasteries, such as the Murfatlar Cave Complex, where excavations have revealed stone relief murals and inscriptions in three alphabets – Glagolitic, Cyrillic and Greek, as well as Bulgar runes.[298]

In the region of Kutmichevitsa to the south-west, Clement of Ohrid oversaw the construction of the Monastery of Saint Panteleimon and two churches with "round and spherical form" in the late 9th century.[299] In 900 the Monastery of Saint Naum was established at the expense of "the pious Bulgarian Tsar Michael-Boris and his son Tsar Simeon" on the shores of Lake Ohrid, some 30 km to the south of the town, as a major literary centre.[292] Other important buildings were the Church of Saint Sophia in Ohrid, and the Basilica of Saint Achillius on an island in Lake Prespa, with dimensions of 30 х 50 m, both modeled after the Great Basilica of Pliska.[300] These churches had three naves and three apses.[293] Preserved edifices from that period evincing the rich and settled Bulgarian culture at the time include three small churches dated from the late 9th or early 10th centuries in Kostur and the church in the village of German (both in modern Greece).[139]

Art