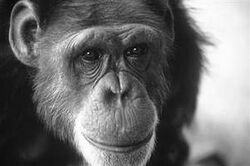

Biology:Washoe (chimpanzee)

| |

| Born | September 1965 West Africa |

|---|---|

| Died | October 30, 2007 (aged 42) Ellensburg, Washington, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Complications from SAIDS |

| Known for | Use of sign language |

Washoe (c. September 1965 – October 30, 2007) was a female common chimpanzee who was the first non-human to learn to communicate using American Sign Language (ASL) as part of an animal research experiment on animal language acquisition.[1]

Washoe learned approximately 350 signs of ASL,[2] also teaching her adopted son Loulis some signs.[3][4][5] She spent most of her life at Central Washington University.

Early life

Washoe was born in West Africa in 1965. She was captured for use by the US Air Force for research for the US space program.[6] Washoe was named after Washoe County, Nevada, where she was raised and taught to use ASL.[7]

In 1967, R. Allen Gardner and Beatrix Gardner established a project to teach Washoe ASL at the University of Nevada, Reno. At the time, previous attempts to teach chimpanzees to imitate vocal languages (the Gua and Viki projects) had failed. The Gardners believed that these projects were flawed because chimpanzees are physically unable to produce the voiced sounds required for oral language. Their solution was to utilize the chimpanzee's ability to create diverse body gestures, which is how they communicate in the wild, by starting a language project based on American Sign Language.[8][9] The Gardners raised Washoe as one would raise a child. She frequently wore clothes and sat with them at the dinner table. Washoe had her own 8-foot-by-24-foot trailer complete with living and cooking areas. The trailer had a couch, drawers, a refrigerator, and a bed with sheets and blankets. She had access to clothing, combs, toys, books, and a toothbrush. Much like a human child, she underwent a regular routine with chores, outdoor play, and rides in the family car.[10] Upon seeing a swan, Washoe signed "water" and "bird". Harvard psychologist Roger Brown said that "was like getting an S.O.S. from outer space".[11]

When Washoe was five, the Gardners decided to move on to other projects, and she was moved to the University of Oklahoma's Institute of Primate Studies in Norman, Oklahoma, under the care of Roger Fouts and Deborah Fouts.[12]

ASL instruction and usage

Teaching method

Washoe was raised in an environment as close as possible to that of a human child, in an attempt to satisfy her psychological need for companionship.[13][14][15]

While with Washoe, the Gardners and Foutses were careful to communicate only in ASL with Washoe, rather than using vocal communication, on the assumption that this would create a less confusing learning environment for Washoe. This technique was said to resemble that used when teaching human children language.[16]

After the first couple of years of the language project, the Gardners and Roger Fouts discovered that Washoe could pick up ASL gestures without direct instruction, but instead by observing humans around her who were signing amongst themselves. For example, the scientists signed "toothbrush" to each other while they brushed their teeth near her. At the time of observation, Washoe showed no signs of having learned the sign, but on a later occasion she reacted to the sight of a toothbrush by spontaneously producing the correct sign, thereby showing that she had in fact previously learned the ASL sign. Moreover, the Gardners began to realize that rewarding particular signs with food and tickles was actually interfering with the intended result of conversational sign language. They changed their strategy so that food and meal times were never juxtaposed with instruction times. In addition, they stopped the tickle rewards during instruction because these generally resulted in laughing breakdowns. Instead, they set up a conversational environment that evoked communication, without the use of rewards for specific actions.[17][verification needed]

Confirmed signs

Washoe learned approximately 350 words of sign languages.[2]

For researchers to consider that Washoe had learned a sign, she had to use it spontaneously and appropriately for 14 consecutive days.[18][19]

These signs were then further tested using a double-blind vocabulary test. This test demonstrated 1) "that the chimpanzee subjects could communicate information under conditions in which the only source of information available to a human observer was the signing of the chimpanzee;" 2) "that independent observers agreed with each other;" and 3) "that the chimpanzees used the signs to refer to natural language categories—that the sign DOG could refer to any dog, FLOWER to any flower, SHOE to any shoe."[20][21]

Combinations of signs

Washoe and her mates were able to combine the hundreds of signs that they learned into novel combinations (that they had never been taught, but rather created themselves) with different meanings. For instance, when Washoe's mate Moja did not know the word for "thermos", Moja referred to it as a "METAL CUP DRINK"; however, whether or not Washoe's combinations constitute genuine inventive language is controversial, as Herbert S. Terrace contended by concluding that seeming sign combinations did not stand for a single item, but rather were three individual signs.[22][23] Taking the thermos example, rather than METAL CUP DRINK being a composite meaning thermos, it could be that Washoe was indicating there was an item of metal (METAL), one shaped like a cup (CUP), and that could be drunk out of (DRINK).

Self-awareness and emotion

One of Washoe's caretakers was pregnant and missed work for many weeks after she miscarried. Roger Fouts recounts the following situation:

People who should be there for her and aren't are often given the cold shoulder—her way of informing them that she's miffed at them. Washoe greeted Kat [the caretaker] in just this way when she finally returned to work with the chimps. Kat made her apologies to Washoe, then decided to tell her the truth, signing "MY BABY DIED". Washoe stared at her, then looked down. She finally peered into Kat's eyes again and carefully signed "CRY", touching her cheek and drawing her finger down the path a tear would make on a human (Chimpanzees don't shed tears). Kat later remarked that one sign told her more about Washoe and her mental capabilities than all her longer, grammatically perfect sentences.[24]

Washoe herself lost two children. One baby chimpanzee died of a heart defect shortly after birth; the other baby, Sequoyah, died of a staph infection at two months of age.

When Washoe was shown an image of herself in the mirror, and asked what she was seeing, she replied: "Me, Washoe."[25][26] Primate expert Jane Goodall, who has studied and lived with chimpanzees for decades, believes that this might indicate some level of self-awareness.[26][27] Washoe appeared to experience an identity crisis when she was first introduced to other chimpanzees, seeming shocked to learn that she was not the only chimpanzee. She gradually came to enjoy associating with other chimpanzees.[28]

Washoe enjoyed playing pretend with her dolls, which she would bathe and talk to and would act out imaginary scenarios.[29][30] She also spent time brushing her teeth, painting and taking tea parties.[31]

When new students came to work with Washoe, she would slow down her rate of signing for novice speakers of sign language, which had a humbling effect on many of them.[32]

Quotes

(In this section double quotes are signed by Washoe, single by someone else.)

- "Peekaboo (i.e. hide and seek) I go"[33]

- "Baby (doll) in my drink (i.e. cup)" (when doll placed in her cup)[33]

- "Time Eat?" and "you me time eat?"[33]

- Asked 'Who's coming?' Responded "Mrs G" (correct).[33]

- "You, Me out go". 'OK but first clothes' (Washoe puts on jacket.)[33]

- "Good, go", 'Where Go', "You Me Peekaboo"[33]

- 'What That' "Shoe" 'Whose That Shoe' "Yours" 'What color' "Black".[33]

Later life and death

Washoe was moved to Central Washington University in 1980. On October 30, 2007, officials from the Chimpanzee and Human Communication Institute on the CWU campus announced that she had died at the age of 42.[6][11]

Impact on bioethics

Some believe that the fact that Washoe not only communicated, but also formed close and personal relationships with humans indicates that she was emotionally sensitive and deserving of moral status.[34]

Work with Washoe and other signing primates motivated the foundation of the Great Ape Project, which hopes to "include the non-human great apes: chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas within the community of equals by granting them the basic moral and legal protections that only humans currently enjoy", in order to place them in the moral category of "persons" rather than private property.[35]

Related animal language projects

The publication of the Washoe experiments spurred a revival in the scholarly study of sign language, due to widespread interest in questions it raised about the biological roots of language.[36] This included additional experiments which attempted to teach great apes language in a more controlled environment.

Herbert Terrace and Thomas Bever's Nim Chimpsky project failed in its attempt to replicate the results of Washoe. While Nim was successfully trained to use 125 signs, Terrace and his colleagues concluded that the chimpanzee did not show any meaningful sequential behavior that rivaled human grammar. Nim's use of language was strictly pragmatic, as a means of obtaining an outcome, unlike a human child's, which can serve to generate or express meanings, thoughts or ideas. There was nothing Nim could be taught that could not equally well be taught to a pigeon using the principles of operant conditioning. The researchers therefore questioned claims made on behalf of Washoe, and argued that the apparently impressive results may have amounted to nothing more than a "Clever Hans" effect, not to mention a relatively informal experimental approach.

Critics of primate linguistic studies include Thomas Sebeok, American semiotician and investigator of nonhuman communication systems, who wrote:

Sebeok also made pointed comparisons of Washoe with Clever Hans. Some evolutionary psychologists, in effect agreeing with Noam Chomsky, argue that the apparent impossibility of teaching language to animals is indicative that the ability to use language is an innately human development.[38]

Washoe's advocates disagreed that the research had been discredited, attributing the failure of the Nim Chimpsky and other projects to poor teaching, and to Nim's being consistently isolated in a sterile laboratory environment, and often confined in cages, for his entire life. Nim did most of his learning in a white eight-foot-by-eight-foot laboratory room (with one of the walls containing a one-way mirror), where he was often trained to use signs without the referent present. Living in this setting, Nim did not receive the same level of nurturing, affection, and life experience, and many have suggested that this impaired his cognitive development, as happens with human children subjected to such an environment.[39][40][41]

Other great ape language research projects, such as on Koko the gorilla, have received similar criticism to Project Washoe as to the selective interpretation of the use of sign language by apes and lack of objectivity.[42]

See also

- Kanzi

- Animal cognition

- Great ape language

- Koko (gorilla)

- List of individual apes

- Alex (parrot), talking parrot

- Batyr (elephant)

References

- ↑ Livingston, John A. (1996). "other selves". in Vitek, William; Jackson, Wes. Rooted in the land: essays on community and place. Yale University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-300-06961-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=NZ3UfrZkSDsC&pg=PA133.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Johnson, Lawrence E. (1993). A morally deep world: an essay on moral significance and environmental ethics. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-521-44706-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=R1byaqvqVKUC&pg=PA27.

- ↑ Fouts, R.H.; Fouts, D.M.; Van Cantfort, T.E. (1989). Gardner, Beatrice; Allen, R.. eds. Teaching sign language to chimpanzees. SUNY Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-88706-965-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=_VN2QrM03MAC&pg=PA281.

- ↑ Fouts, Roger S.; Waters, Gabriel S. (2002). "Continuity, Ethology, and Stokoe: How to Build a Better Language Model". in Stokoe, William C.; Armstrong, David F.. The study of signed languages: essays in honor of William C. Stokoe. Gallaudet University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pc-Rcg2-L0UC&pg=107.

- ↑ Byrne, Richard W. (1999). "Primate cognition: evidence for the ethical treatment of primates". in Dolins, Francine L.. Attitudes to animals: views in animal welfare. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-521-47906-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=qregiFqILWMC&pg=PA119.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 ""Signing" chimp Washoe broke language barrier". The Seattle Times. November 1, 2007. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2003986892_washoe01m.html.

- ↑ Gardner, R. Allen, Beatrix T. Gardner, and Thomas E. Van Cantfort. Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees. State University of New York Press, 1989, p. 1

- ↑ Goodall, Jane (September 1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-11649-8. https://archive.org/details/chimpanzeesofgom00good.

- ↑ Goodall, Jane (April 1, 1996). My Life with the Chimpanzees (Revised ed.). Aladdin. ISBN 978-0-671-56271-7. https://archive.org/details/mylifewithchimpa00good.

- ↑ Prof. Mark Kruase, Southern Oregon University, January 20, 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Carey, Benedict (November 1, 2007). "Washoe, a Chimp of Many Words, Dies at 42". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/science/01chimp.html.

- ↑ Hillix, William A.; Rumbaugh, Duane P. (2004). Animal bodies, human minds: ape, dolphin, and parrot language skills. Springer. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-306-47739-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=MluTYjQ6qVUC&pg=PA87.

- ↑ Hillix, William A.; Rumbaugh, Duane P. (2004). Animal bodies, human minds: ape, dolphin, and parrot language skills. Springer. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-306-47739-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=MluTYjQ6qVUC&pg=PA69.

- ↑ Dresser, Norine (2005). "The horse bar mitzvah: a celebratory exploration of the human-animal bond". in Podberscek, Anthony L.. Companion Animals and Us: Exploring the Relationships Between People and Pets. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-521-01771-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=tSs2yV_F4n0C&pg=PA91.

- ↑ Fouts, Roger S.; Deborah H. Fouts (1993). "Chimpanzees' Use of Sign Language". in Cavalieri, Paola; Singer, Peter. The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity. Macmillan. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-312-11818-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=8RMSPt0kC_kC&pg=PA28.

- ↑ Orlans, F. Barbara (1998). "Washoe and Her Successors". The human use of animals: case studies in ethical choice. Oxford University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=yBWL1t2b_w0C&pg=PA140.

- ↑ Gardner, R. A.; Gardner, B. T. (1998). The structure of learning from sign stimuli to sign language. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ↑ Wise, Stephen M. (2003). Drawing the line: science and the case for animal rights. Basic Books. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7382-0810-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Wq7kZBdvIcC&pg=PA200.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Hillix, William A.; Rumbaugh, Duane P. (2004). Animal bodies, human minds: ape, dolphin, and parrot language skills. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-306-47739-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=MluTYjQ6qVUC&pg=PA82.

- ↑ Gardner, R. A. & Gardner, B. T. (1984). A vocabulary test for chimpanzees. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 98, pg. 381–404

- ↑ Gardner, R. A.; Gardner, B. T. (1984). "A vocabulary test for chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)". Journal of Comparative Psychology 98 (4): 381–404. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.98.4.381. PMID 6509904.

- ↑ Hillix, William A.; Rumbaugh, Duane P. (2004). Animal bodies, human minds: ape, dolphin, and parrot language skills. Springer. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-306-47739-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=MluTYjQ6qVUC&pg=PA71.

- ↑ Sapolsky, Robert M. Human Behavioral Biology 23:Language. Stanford University. May 2010

- ↑ Donovan, James M.; Anderson, H. Edwin (2006). Anthropology & Law. Berghahn Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-57181-424-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=gb35_pWmcDwC&pg=PA190.

- ↑ Mitchell, Robert W. (2002). "A history of pretense in animals and children". in Mitchell, Robert W.. Pretending and imagination in animals and children. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-77030-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=pnycVZXcPrEC&pg=PA40.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (2010). "The Behavior of Chimpanzees in their Natural Habitat". in Cohen, Yehudi. Human Adaptation: The Biosocial Background. Aldine Transaction. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-202-36384-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=hW1sPY90eeMC&pg=PA113.

- ↑ Peterson, Dale; Goodall, Jane (2000). Visions of Caliban: On Chimpanzees and People. University of Georgia Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-8203-2206-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=-CvJnqkHaAYC&pg=PA21.

- ↑ Blum, Deborah (1995). The Monkey Wars. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-19-510109-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=OiEn9kxamE0C&pg=PA15.

- ↑ Gómez, Juan-Carlos; Martín-Andrade, Beatriz (2005). "Fantasy Play in Apes". in Pellegrini, Anthony D.; Smith, Peter K.. The nature of play: great apes and humans. Guilford Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-59385-117-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Nukz6dJNCO0C&pg=PA153.

- ↑ McCune, L.; Agayoff, J. (2002). "Pretending as representation". in Mitchell, Robert W.. Pretending and imagination in animals and children. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-77030-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=pnycVZXcPrEC&pg=PA51.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Meet Washoe – Friends of Washoe". http://www.friendsofwashoe.org/meet/washoe.html.

- ↑ Fouts, Roger S. (2008). "Foreword". in McMillan, Franklin D.. Mental Health and Well-Being in Animals. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8138-0489-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=vxS9FZfv4jMC&pg=PR15.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 Extract from Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees, Gardiner

- ↑ Fern, Richard L. (2002). Nature, God and humanity: envisioning an ethics of nature. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-00970-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=gJAoyQaavZsC&pg=PA20.

- ↑ Guerrini, Anita (2003). Experimenting with humans and animals: from Galen to animal rights. JHU Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8018-7197-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=8as-dLk-6N0C&pg=PA135.

- ↑ Kendon, Adam (2002). "Historical Observations on the Relationship Between Research on Sign Languages and Language Origins Theory". in Stokoe, William C.; Armstrong, David F.. The study of signed languages: essays in honor of William C. Stokoe. Gallaudet University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pc-Rcg2-L0UC&pg=PA45.

- ↑ Wade, N. (1980). "Does man alone have language? Apes reply in riddles, and a horse says neigh". Science 208: pp. 1349–1351.

- ↑ Pinker, S.; Bloom, P. (1990). "Natural language and natural selection". Behavioral and Brain Sciences 13: pp. 707–784.

- ↑ Lieberman, Philip (1998). Eve spoke: human language and human evolution. W.W. Norton & Co.. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-393-04089-0. https://archive.org/details/evespokehumanlan00lieb.

- ↑ Miles, H. Lyn (1997). "Anthropomorphism, Apes, and Language". in Mitchell, Robert W.. Anthropomorphism, anecdotes, and animals. SUNY Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-7914-3125-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=1kWZt3de0loC&pg=PA389.

- ↑ Hillix, William A.; Rumbaugh, Duane M. (1998). "Language in Animals". in Greenberg, Gary; Haraway, Maury M.. Comparative psychology: a handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 841. ISBN 978-0-8153-1281-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wx89TPdv4h0C&pg=PA841.

- ↑ Herbert Terrace (December 4, 1980). More on Monkey Talk. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1980/12/04/more-on-monkey-talk-1/. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

Further reading

- Fouts, Roger (1997). Next of Kin: what chimpanzees have taught me about who we are. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-14862-X.

- Beckoff, Marc, ed (2010). "Chimpanzees in captivity". Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-313-35257-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=AmgYIBQ-XKkC&pg=PA112.

- Wolfe, Cary (2003). "In the Shadow of Wittgenstein's Lion: Language, Ethics, and the Question of the Animal". in Wolfe, Cary. Zoontologies: the question of the animal. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4105-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=FGvX6wnM_aUC&pg=PA1.

External links

- Friends of Washoe—a non-profit organization

- A conversation with Warshoe – When Her Caretaker Told The Chimp She Had Lost Her Baby

|