Philosophy:Self-awareness

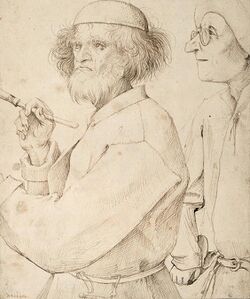

In this drawing by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, the painter is thought to be a self-portrait.

In philosophy of self, self-awareness is the experience of one's own personality or individuality.[1] It is not to be confused with consciousness in the sense of qualia. While consciousness is being aware of one's body and environment, self-awareness is the recognition of that consciousness.[2] Self-awareness is how an individual experiences and understands their own character, feelings, motives, and desires.

Biology

Mirror neurons

Researchers are investigating which part of the brain allows people to be self-aware and how people are biologically programmed to be self-aware. V.S. Ramachandran speculates that mirror neurons may provide the neurological basis of human self-awareness.[3] In an essay written for the Edge Foundation in 2009, Ramachandran gave the following explanation of his theory: "[T]hese neurons can not only help simulate other people's behavior but can be turned 'inward'—as it were—to create second-order representations or meta-representations of your own earlier brain processes. This could be the neural basis of introspection, and of the reciprocity of self awareness and other awareness. There is obviously a chicken-or-egg question here as to which evolved first, but... The main point is that the two co-evolved, mutually enriching each other to create the mature representation of self that characterizes modern humans."[4]

Body

Bodily (self-)awareness is related to proprioception and visualization.[5]

Health

In health and medicine, body awareness refers to a person's ability to direct their focus on various internal sensations accurately. Both proprioception and interoception allow individuals to be consciously aware of multiple sensations.[6] Proprioception allows individuals and patients to focus on sensations in their muscles and joints, posture, and balance, while interoception is used to determine sensations of the internal organs, such as fluctuating heartbeat, respiration, lung pain, or satiety. Over-acute body-awareness, under-acute body-awareness, and distorted body-awareness are symptoms present in a variety of health disorders and conditions, such as obesity, anorexia nervosa, and chronic joint pain.[7] For example, a distorted perception of satiety present in a patient suffering from anorexia nervosa.[sentence fragment]

Human development

Bodily self-awareness in human development refers to one's awareness of one's body as a physical object with physical properties that can interact with other objects. At only a few months old, toddlers know the relationship between the proprioceptive and visual information they receive.[8] This is called "first-person self-awareness".

By around 18 months of age, children begin to develop reflective self-awareness, which is the next stage of bodily awareness. It involves children recognizing themselves in reflections, mirrors, and pictures.[9] Children who have not obtained this stage of bodily self-awareness tend to view reflections of themselves as other children and respond accordingly, as if they were looking at someone else face to face. In contrast, those who reach this level of awareness recognize that they see themselves, for instance, seeing dirt on their face in the reflection and then touching their face to wipe it off.

Soon after toddlers become reflectively self-aware, they begin to recognize their bodies as physical objects in time and space that interact and impact other objects. For instance, a toddler placed on a blanket, when asked to hand someone the blanket, will recognize that they need to get off it to be able to lift it.[8] This is the final stage of body self-awareness and is called objective self-awareness.

Non-human animals

"Mirror tests" have been done on chimpanzees, elephants, dolphins and magpies. During the test, the experimenter looks for the animals to undergo four stages:[10]

- social response (behaving toward the reflection as they would toward another animal of their species)

- physical mirror inspection

- repetitive mirror testing behavior, and

- the mark test, which involves the animals spontaneously touching a mark on their body that would have been difficult to see without the mirror

The red-spot technique, created by Gordon G. Gallup,[11] studies self-awareness in primates. This technique places a red odorless spot on an anesthetized primate's forehead. The spot is placed on the forehead so it can only be seen through a mirror. Once the primate awakens, its independent movements toward the spot after it sees its reflection in a mirror are observed.

Apes

Chimpanzees and other apes—extensively studied species—are most similar to humans, with the most convincing findings and straightforward evidence of self-awareness in animals.[12]

Chimpanzees

During the red-spot technique, after looking in the mirror, chimpanzees used their fingers to touch the red dot on their forehead and, after touching the red dot they would smell their fingertips.[13] "Animals that can recognize themselves in mirrors can conceive of themselves," says Gallup.

Dolphins

Dolphins were put to a similar test and achieved the same results. Diana Reiss, a psycho-biologist at the New York Aquarium discovered that bottlenose dolphins can recognize themselves in mirrors.[14]

Elephants

Three elephants were exposed to large mirrors and experimenters studied their reactions when the elephants saw their reflections. These elephants were given the "litmus mark test"[definition needed] to see whether they were aware of what they were looking at. This visible mark was applied on the elephants and the researchers reported large progress[specify] with self-awareness.[10]

Magpies

Researchers also used the mark or mirror tests to study the magpie's self-awareness.[15] As a majority of birds are blind below the beak, Prior et al. marked the birds' neck with three different colors: red, yellow, and black (as an imitation, as magpies are originally black). When placed in front of a mirror, the birds with red and yellow spots began scratching at their necks, signaling the understanding of something different being on their bodies. During one trial with a mirror and a mark, three of the five magpies showed at least one example of self-directed behavior. The magpies explored the mirror by moving toward it and looking behind it. One of the magpies, Harvey, during several trials would pick up objects, pose, do some wing-flapping, all in front of the mirror with the objects in his beak. This represents a sense of self-awareness; knowing what is going on within himself and in the present. The authors suggest that self-recognition in birds and mammals may be a case of convergent evolution, where similar evolutionary pressures result in similar behaviors or traits, although they arrive at them via different routes.[16]

A few slight occurrences of behavior towards the magpie's own body happened in the trial with the black mark and the mirror. The authors of this study suggest that the black mark may have been slightly visible on the black feathers. "This is an indirect support for the interpretation that the behavior towards the mark region was elicited by seeing the own body in the mirror in conjunction with an unusual spot on the body."[15]

There was a clear contrast between the behaviors of the magpies when a mirror was present versus absent. In the no-mirror trials, a non-reflective gray plate was swapped in the same size and position as the mirror. There were not any mark-directed self-behaviors when the mark was present, in color or in black.[15] The results show that magpies understand that a mirror image represents their own body; magpies have self-awareness.

Three "types" of self-awareness

David DeGrazia identifies three types of self-awareness which animals may share with humans:[17]

- Bodily self-awareness

- This allows animals to understand that they are different from the rest of the environment. It explains why animals do not eat themselves. Bodily-awareness also includes proprioception and sensation.

- Social self-awareness

- Seen in highly social animals, this awareness allows animals to interact with each other.

- Introspective self-awareness

- This is how animals might sense feelings, desires, and beliefs.

Cooperation and evolutionary problems

An organism can be effectively altruistic without being self-aware, aware of any distinction between egoism and altruism, or aware of qualia in others. It can do this via simple reactions to specific situations that benefit other individuals in the organism's environment. If self-awareness led to a necessity of an emotional empathy mechanism for altruism and egoism being default in its absence, that would have precluded evolution from a state without self-awareness to a self-aware state in all social animals.Template:Copy edit inline The ability of the theory of evolution to explain self-awareness can be rescued by abandoning the hypothesis of self-awareness being a basis for cruelty.[dubious ][18]

Psychology

Self-awareness has been called "arguably the most fundamental issue in psychology, from both a developmental and an evolutionary perspective."[19]

Self-awareness theory, developed by Duval and Wicklund in their 1972 landmark book A theory of objective self awareness, states that when we focus on ourselves, we evaluate and compare our current behavior to our internal standards and values. This elicits a state of objective self-awareness. We become self-conscious as objective evaluators of ourselves.[20] Self-awareness should not be confused with self-consciousness.[21] Various emotional states are intensified by self-awareness. However, some people may seek to increase their self-awareness through these outlets[specify]. People are more likely to align their behavior with their standards when they are made self-aware. People are negatively affected if they do not live up to their personal standards. Various environmental cues and situations induce awareness of the self, such as mirrors, an audience, or being videotaped or recorded. These cues also increase the accuracy of personal memory.[22]

In one of Andreas Demetriou's neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development, self-awareness develops systematically from birth through the life span and it is a major factor for the development of[clarification needed] general inferential processes.[23] Self-awareness about cognitive processes contributes to general intelligence on a par with[ambiguous] processing efficiency functions, such as working memory, processing speed, and reasoning.[24]

Albert Bandura's theory of self-efficacy describes "the belief in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations." A person's belief in their ability to succeed sets the stage for how they think, behave, and feel. Someone with a strong self-efficacy, for example, views challenges as tasks to engage in, and is not easily discouraged by setbacks. Such a person is aware of their flaws and abilities and chooses to utilize these qualities to the best of their ability. Someone with a weak sense of self-efficacy evades challenges and quickly feels discouraged by setbacks. They may not be aware of these negative reactions and therefore, may not be prompted to change their attitude. This concept is central to Bandura's social cognitive theory, "which emphasizes the role of observational learning, social experience, and reciprocal determinism in the development of personality."[25][unreliable source?]

Developmental stages

Individuals become conscious of themselves through the development of self-awareness.[19] This particular type of self-development pertains to becoming conscious of one's body and one's state of mind—including thoughts, actions, ideas, feelings, and interactions with others.[26] "Self-awareness does not occur suddenly through one particular behavior: it develops gradually through a succession of different behaviors all of which relate to the self."[27] The monitoring of one's mental states is called metacognition and is considered to be an indicator that there is some concept of the self.[28] It is developed through an early[compared to?] sense of non-self components[specify] using sensory and memory sources. In developing self-awareness through self-exploration and social experiences, one can broaden one's social world and become more familiar with the self.[clarification needed]

According to Philippe Rochat, there are five levels of self-awareness that unfold in early human development and six potential prospects ranging from "Level 0" (having no self-awareness) advancing complexity to "Level 5" (explicit self-awareness):[19]

- Level 0—Confusion

- The person is unaware of any mirror reflection or the mirroring itself; they perceive a mirror image as an extension of their environment. Level 0 can also be displayed when an adult frightens themself in a mirror, mistaking their own reflection as another person just for a moment.

- Level 1—Differentiation

- The individual realizes the mirror is able to reflect things. They see that what is in the mirror is of a different nature from what is surrounding them. At this level they can differentiate between their own movement in the mirror and the movement of the surrounding environment.

- Level 2—Situation

- The individual can link the movements on the mirror to what is perceived within their own body. This is the first hint of self-exploration on a projected surface where what is visualized on the mirror is special to the self.

- Level 3—Identification

- This stage is characterized by the new ability to identify self: an individual can now see that what's in the mirror is not another person but actually them. This is seen when a child, instead of referring to the mirror while referring to themselves, refers to themselves while looking in the mirror.

- Level 4—Permanence

- Once an individual reaches this level they can identify the self beyond the present mirror imagery. They are able to identify the self in previous pictures looking different or younger. A "permanent self" is now experienced.

- Level 5—Self-consciousness or "meta" self-awareness

- At this level not only is the self seen from a first person view but it is realized that it is also seen from a third person's view. A person who develops self consciousness begins to understand they can be in the mind of others: for instance, how they are seen from a public standpoint.

Infancy and early childhood

When a human infant comes into the world, they have no concept of what is around them, nor the significance of others around them.[29]:46 During their first year they gradually begin to acknowledge that their body is separate from that of their mother, and that they are an "active, causal agent in space". By the end of the first year, they additionally realize that their movement, as well, is separate from the movement of the mother.

At first "the infant cannot recognize its own face".[29]:46 By the time an average toddler reaches 18–24 months, they discover themselves and recognize their own reflection in the mirror,[30] however the exact age varies with differing socioeconomic levels and differences relating to culture and parenting.[31] They begin to acknowledge the fact that the image in front of them, who happens to be them, moves; indicating that they appreciate and can consider the relationship between cause and effect that is happening.Template:Copy edit inline[29]

By the age of 24 months the toddler will observe and relate their own actions to actions of other people and the surrounding environment.[30] Once an infant has gotten a lot of experience in front of a mirror, they can recognize themselves in the reflection, and understand that it is them.Template:Repetition inline For example, in a study, an experimenter took a red marker and put a fairly large red dot (so it is visible by the infant) on the infant's nose, and placed them in front of a mirror. Prior to 15 months of age, the infant will not react to this, but after 15 months of age, they will either touch their nose, wondering what it is they have on their face, or point to it. This indicates that they recognize that the image they see in the reflection of the mirror is themselves.[8] A mirror-self recognition task has been used as a research tool for years, and has led to key foundations of the infant's sense/awareness of self.[8] For example,[non sequitur] "for Piaget, the objectification of the bodily self occurs as the infant becomes able to represent the body's spatial and causal relationship with the external world".[8] Facial recognition places a big pivotal point in their[clarification needed] development of self-awareness.[29]

By 18 months of age, an infant can communicate their name to others, and upon being shown a picture they are in, they can identify themselves. By two years old, they also usually acquire gender category and age categories, saying things such as "I am a girl, not a boy" and "I am a baby or child, not a grownup". As an infant moves to middle childhood and onwards to adolescence, they develop more advanced levels of self-awareness and self-description.[29]

As infants develop their senses, using multiple senses of in order to recognize what is around them, infants can become affected by something known as "facial multi stimulation".Template:Copy edit inline In one experiment by Filippetti, Farroni, and Johnson, an infant of around five months in age is presented with what is known as an "enfacement illusion".[32] "Infants watched a side-by-side video display of a peer's face being systematically stroked on the cheek with a paintbrush. During the video presentation, the infant's own cheek was stroked in synchrony with one video and in asynchrony with the other".[32] Infants were proven to recognize and project an image of a peer with that of their own[clarification needed] , showing beginning signs of facial recognition cues onto one's self, with the assistance of such an illusion.

Piaget

Around school age, a child's awareness of their memory transitions into a sense of their self. At this stage, a child begins to develop interests, likes, and dislikes. This transition enables a person's awareness of their past, present, and future to grow as they remember their conscious experiences more often.[30] As a preschooler, they begin to give much more specific details about things, instead of generalizing. For example, the preschooler will talk about the Los Angeles Lakers basketball team, and the New York Rangers hockey team, instead of the infant just stating that they like sports. Furthermore, they will start to express certain preferences (e.g., Tod likes mac and cheese) and will start to identify certain possessions of theirs (e.g., Lara has a bird as a pet at home). At this age, the infant is in what Piaget names the pre operational stage of development. The infant is very inaccurate at judging themselves because they do not have much to go on. For example, an infant at this stage will not associate that they are strong with their ability to cross the jungle gym at their school, nor will they associate the fact that they can solve a math problem with their ability to count.[29]

Adolescence

One becomes conscious of one's emotions during adolescence. Most children are aware of emotions such as shame, guilt, pride, and embarrassment by the age of two, but do not fully understand how those emotions affect their life.[33][page needed] By age 13, children become more in touch with these emotions and begin to apply them to their lives. Many adolescents display happiness and self-confidence around friends, but hopelessness and anger around parents due to the fear of being a disappointment. Teenagers feel intelligent and creative around teachers; shy, uncomfortable, and nervous around people they are not familiar with.[34]

In adolescent development, self-awareness has a more complex emotional context than in the early childhood phase. Elements can include self-image, self-concept, and self–consciousness among other traits that relate to Rochat's final level of self awareness, however it[ambiguous] is still a distinct concept.[35] Social interactions mainly separate the element of self-awareness in adolescent rather than in childhood, as well as further developed emotional recognition skills in adolescents.Template:Copy edit inline

Mental health

As children reach adolescence, their acute sense of emotion has widened into a meta-cognitive state in which mental health issues can become more prevalent due to their[ambiguous] heightened emotional and social development.[36] Elements of contextual behavioral science[definition needed] involved with adolescent self-awareness, such as Self-as-Content, Self-as-Process, and Self-as-Context, [vague] mental health.[36]

Anger management is also [vague] self-awareness in teens.[37] Self-awareness training may reduce anger management issues and reduce aggressive tendencies in adolescents: "Persons having sufficient self-awareness promote relaxation and awareness about themselves and when going angry, at the first step they become aware of anger in their inside and accept it, then try to handle it".[37]

Philosophy

Locke

An early philosophical discussion of self-awareness is that of John Locke. Locke was apparently influenced by René Descartes's statement, normally translated as "I think, therefore I am" (cogito ergo sum). In Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) he conceptualized consciousness as the repeated self-identification of oneself through which moral responsibility could be attributed to the subject—and therefore punishment and guiltiness justified.

Nietzsche would point out that this affirms "the psychology of conscience... is not 'the voice of God in man'; it is the instinct of cruelty... one of the oldest and most indispensable elements in the foundation of culture."[38]

Locke does not use the terms self-awareness or self-consciousness. According to Locke, personal identity (the self) "depends on consciousness, not on substance".[39] A person is the same person to the extent that the person is conscious of their past and future thoughts and actions in the same way as they are conscious of their present thoughts and actions. If consciousness is this "thought" which doubles all thoughts, then personal identity is only founded on the repeated act of consciousness: "This may show us wherein personal identity consists: not in the identity of substance, but... in the identity of consciousness."[40](§19) For example, one may claim to be a reincarnation of Plato, therefore having the same soul. However, one would be the same person as Plato only if one had the same consciousness of Plato's thoughts and actions that he himself did. Therefore, self-identity is not based on the soul. One soul may have various personalities.[39]

Locke argues that self-identity is not founded either on the body or the substance, as the substance may change while the person remains the same. "Animal identity is preserved in identity of life, and not of substance", as the body of the animal grows and changes during its life.[40] Locke describes a case of a prince and a cobbler in which the soul of the prince is transferred to the body of the cobbler and vice versa. The prince still views himself as a prince, though he no longer looks like one.[40] This border-case leads to the problematic thought that since personal identity is based on consciousness, and that only oneself can be aware of one's consciousness, exterior human judges may never know if they really are judging—and punishing—the same person, or simply the same body. Locke argues that one may be judged for the actions of one's body rather than one's soul, and only God knows how to correctly judge a man's actions. Men also are only responsible for the acts of which they are conscious. This forms the basis of the insanity defense which argues that one cannot be held accountable for acts for which they were unconsciously irrational.[41] In reference to man's personality, Locke claims that "whatever past actions it cannot reconcile or appropriate to that present self by consciousness, it can be no more concerned in, than if they had never been done: and to receive pleasure or pain, i.e. reward or punishment, on the account of any such action, is all one as to be made happy or miserable in its first being, without any demerit at all."[40]

Disorders

The medical term for not being aware of one's deficits is anosognosia, or more commonly known as a lack of insight. Having a lack of awareness raises the risks of treatment and service nonadherence.[42] Individuals who deny having an illness may be against seeking professional help because they are convinced that nothing is wrong with them. Disorders of self-awareness frequently follow frontal lobe damage.[43] There are two common methods used to measure how severe an individual's lack of self-awareness is. The Patient Competency Rating Scale (PCRS) evaluates self-awareness in patients who have endured a traumatic brain injury.[44] PCRS is a 30-item self-report instrument which asks the subject to use a 5-point Likert scale to rate his or her degree of difficulty in a variety of tasks and functions. Independently, relatives or significant others who know the patient well are also asked to rate the patient on each of the same behavioral items. The difference between the relatives' and patient's perceptions is considered an indirect measure of impaired self-awareness. The limitations of this experiment rest on the answers of the relatives. Results of their answers can lead to a bias. This limitation prompted a second method of testing a patient's self-awareness. Simply asking a patient why they are in the hospital or what is wrong with their body can give compelling answers as to what they see and are analyzing.[45]

Anosognosia

Anosognosia was a term coined by Joseph Babinski to describe the clinical condition in which an individual suffered from left hemiplegia following a right cerebral hemisphere stroke yet denied that there were any problems with their left arm or leg. This condition is known as anosognosia for hemiplegia (AHP). This condition has evolved throughout the years and is now used to describe people who lack subjective experience in both neurological and neuropsychological cases.[46] A wide variety of disorders are associated with anosognosia. For example, patients who are blind from cortical lesions might in fact be unaware that they are blind and may state that they do not suffer from any visual disturbances. Individuals with aphasia and other cognitive disorders may also suffer from anosognosia as they are unaware of their deficiencies and when they make certain speech errors, they may not correct themselves due to their unawareness.[47] Individuals who suffer from Alzheimer's disease lack awareness; this deficiency becomes more intense throughout their disease.[48] A key issue with this disorder is that people who do have anosognosia and suffer from certain illnesses may not be aware of them, which ultimately leads them to put themselves in dangerous positions and/or environments.[47] To this day there are still no available treatments for AHP, but it has been documented that temporary remission has been used following vestibular stimulation.[49]

Dissociative identity disorder

Dissociative identity disorder or multiple personality disorder (MPD) is a disorder involving a disturbance of identity in which two or more separate and distinct personality states (or identities) control an individual's behavior at different times.[50] One identity may be different from another, and when an individual with DID is under the influence of one of their identities, they may forget their experiences when they switch to the other identity. "When under the control of one identity, a person is usually unable to remember some of the events that occurred while other personalities were in control."[51] They may experience time loss, amnesia, and adopt different mannerisms, attitudes, speech and ideas under different personalities. They are often unaware of the different lives they lead or their condition in general, feeling as though they are looking at their life through the lens of someone else, and even being unable to recognize themselves in a mirror.[52] Two cases of DID have brought awareness to the disorder, the first case being that of Eve. This patient harbored three different personalities: Eve White the good wife and mother, Eve Black the party girl, and Jane the intellectual. Under stress, her episodes would worsen. She even tried to strangle her own daughter and had no recollection of the act afterward. Eve went through years of therapy before she was able to learn how to control her alters and be mindful of her disorder and episodes. Her condition, being so rare at the time, inspired the book and film adaptation The Three Faces of Eve, as well as a memoir by Eve herself entitled I'm Eve. Doctors speculated that growing up during the Depression and witnessing horrific things being done to other people could have triggered emotional distress, periodic amnesia, and eventually DID.[53] In the second case, Shirley Ardell Mason, or Sybil, was described as having over 16 separate personalities with different characteristics and talents. Her accounts of horrific and sadistic abuse by her mother during childhood prompted doctors to believe that this trauma caused her personalities to split, furthering the unproven idea that this disorder was rooted in child abuse, while also making the disorder famous. In 1998 however, Sybil's case was exposed as a sham. Her therapist would encourage Sybil to act as her other alter ego although she felt perfectly like herself. Her condition was exaggerated in order to seal book deals and television adaptations.[53] Awareness of this disorder began to crumble shortly after this finding. To this day, no proven cause of DID has been found, but treatments such as psychotherapy, medications, hypnotherapy, and adjunctive therapies have proven to be very effective.[54]

Autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a range of neurodevelopmental disabilities that can adversely impact social communication and create behavioral challenges (Understanding Autism, 2003).[55] "Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and autism are both general terms for a group of complex disorders of brain development. These disorders are characterized, in varying degrees, by difficulties in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication and repetitive behaviors."[56] ASDs can also cause imaginative abnormalities and can range from mild to severe, especially in sensory-motor, perceptual and affective dimensions.[57] Children with ASD may struggle with self-awareness and self acceptance. Their different thinking patterns and brain processing functions in the area of social thinking and actions may compromise their ability to understand themselves and social connections to others.[58] About 75% diagnosed autistics are mentally handicapped in some general way and the other 25% diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome show average to good cognitive functioning.[59] It is well known that children suffering from varying degrees of autism struggle in social situations. Scientists at the University of Cambridge have produced evidence that self-awareness is a main problem for people with ASD. Researchers used functional magnetic resonance scans (FMRI) to measure brain activity in volunteers being asked to make judgments about their own thoughts, opinions, preferences, as well as about someone else's. One area of the brain closely examined was the ventromedial pre-frontal cortex (vMPFC) which is known to be active when people think about themselves.[60]

A study out of Stanford University has tried to map out brain circuits with understanding self-awareness in Autism Spectrum Disorders.[61] This study suggests that self-awareness is primarily lacking in social situations but when in private they are more self-aware and present. It is in the company of others while engaging in interpersonal interaction that the self-awareness mechanism seems to fail. Higher functioning individuals on the ASD scale have reported that they are more self-aware when alone unless they are in sensory overload or immediately following social exposure.[62] Self-awareness dissipates when an autistic is faced with a demanding social situation. This theory suggests that this happens due to the behavioral inhibitory system which is responsible for self-preservation. This is the system that prevents human from self-harm like jumping out of a speeding bus or putting our hand on a hot stove. Once a dangerous situation is perceived then the behavioral inhibitory system kicks in and restrains our activities. "For individuals with ASD, this inhibitory mechanism is so powerful, it operates on the least possible trigger and shows an over sensitivity to impending danger and possible threats.[62] Some of these dangers may be perceived as being in the presence of strangers, or a loud noise from a radio. In these situations self-awareness can be compromised due to the desire of self preservation, which trumps social composure and proper interaction.

The Hobson hypothesis reports that autism begins in infancy due to a lack of cognitive and linguistic engagement, which results in impaired reflective self-awareness. In this study ten children with Asperger Syndrome were examined using the Self-understanding Interview. This interview was created by Damon and Hart and focuses on seven core areas or schemas that measure the capacity to think in increasingly difficult levels. This interview will estimate the level of self understanding present. "The study showed that the Asperger group demonstrated impairment in the 'self-as-object' and 'self-as-subject' domains of the Self-understanding Interview, which supported Hobson's concept of an impaired capacity for self-awareness and self-reflection in people with ASD."[63] Self-understanding is a self description in an individual's past, present and future. Without self-understanding it is reported that self-awareness is lacking in people with ASD.

Joint attention (JA) was developed as a teaching strategy to help increase positive self-awareness in those with autism spectrum disorder.[64] JA strategies were first used to directly teach about reflected mirror images and how they relate to their reflected image. Mirror Self Awareness Development (MSAD) activities were used as a four-step framework to measure increases in self-awareness in those with ASD. Self-awareness and knowledge is not something that can simply be taught through direct instruction. Instead, students acquire this knowledge by interacting with their environment.[64] Mirror understanding and its relation to the development of self leads to measurable increases in self-awareness in those with ASD. It also proves to be a highly engaging and highly preferred tool in understanding the developmental stages of self- awareness.

There have been many different theories and studies done on what degree of self-awareness is displayed among people with autism spectrum disorder. Scientists have done research about the various parts of the brain associated with understanding self and self-awareness. Studies have shown evidence of areas of the brain that are impacted by ASD. Other theories suggest that helping an individual learn more about themselves through Joint Activities, such as the Mirror Self Awareness Development may help teach positive self-awareness and growth. In helping to build self-awareness it is also possible to build self-esteem and self acceptance. This in turn can help to allow the individual with ASD to relate better to their environment and have better social interactions with others.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric illness characterized by excessive dopamine activity in the mesolimbic tract and insufficient dopamine activity in the mesocortical pathway, leading to symptoms of psychosis along with poor cognition in socialization. Under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, people with schizophrenia have a combination of positive, negative and psychomotor symptoms. These cognitive disturbances involve rare beliefs and/or thoughts of a distorted reality that creates an abnormal pattern of functioning for the patient. The cause of schizophrenia has a substantial genetic component involving many genes. While the heritability of schizophrenia has been found to be around 80%, only about 40% of sufferers report a positive family history of the disorder, and ultimately the cause is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[65] It is believed that the experience of stressful life events is an environmental factor that can trigger the onset of schizophrenia in individuals who already are at risk from genetics and age.[66] The level of self-awareness among patients with schizophrenia is a heavily studied topic.

Schizophrenia as a disease state is characterized by severe cognitive dysfunction and it is uncertain to what extent patients are aware of this deficiency. Medalia and Lim (2004) investigated patients' awareness of their cognitive deficit in the areas of attention, nonverbal memory, and verbal memory.[67] Results from this study (N=185) revealed large discrepancy in patients' assessment of their cognitive functioning relative to the assessment of their clinicians. Though it is impossible to access one's consciousness and truly understand what a schizophrenic believes, regardless in this study, patients were not aware of their cognitive dysfunctional reasoning. In the DSM-5, to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia, they must have two or more of the following symptoms in the duration of one month: delusions*, hallucinations*, disorganized speech*, grossly disorganized/catatonic behavior and negative symptoms (*these three symptoms above all other symptoms must be present to correctly diagnose a patient.) Sometimes these symptoms are very prominent and are treated with a combination of antipsychotics (i.e. haloperidol, loxapine), atypical antipsychotics (such as clozapine and risperidone) and psychosocial therapies that include family interventions and socials skills. When a patient is undergoing treatment and recovering from the disorder, the memory of their behavior is present in a diminutive amount; thus, self-awareness of diagnoses of schizophrenia after treatment is rare, as well as subsequent to onset and prevalence in the patient.

The above findings are further supported by a study conducted by Amador and colleagues.[68] The study suggests a correlation exists between patient insight, compliance, and disease progression. Investigators assess insight of illness was assessed via Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder and was used along with rating of psychopathology, course of illness, and compliance with treatments in a sample of 43 patients. Patients with poor insight are less likely to be compliant with treatment and are more likely to have a poorer prognosis. Patients with hallucinations sometimes experience positive symptoms, which can include delusions of reference, thought insertion/withdrawal, thought broadcast, delusions of persecution, grandiosity, and many more. These psychoses skew the patient's perspectives of reality in ways in which they truly believe are really happening. For instance, a patient that is experiencing delusions of reference may believe while watching the weather forecast that when the weatherman says it will rain, he is really sending a message to the patient in which rain symbolizes a specific warning completely irrelevant to what the weather is. Another example would be thought broadcast, which is when a patient believes that everyone can hear their thoughts. These positive symptoms sometimes are so severe to where the schizophrenic believes that something is crawling on them or smelling something that is not there in reality. These strong hallucinations are intense and difficult to convince the patient that they do not exist outside of their cognitive beliefs, making it extremely difficult for a patient to understand and become self-aware that what they are experiencing is in fact not there.

Furthermore, a study by Bedford and Davis[69] (2013) was conducted to look at the association of denial vs. acceptance of multiple facets of schizophrenia (self-reflection, self-perception, and insight) and its effect on self-reflection (N=26). Study results suggest patients with increased disease denial have lower recollection for self-evaluated mental illnesses. To a great extent, disease denial creates a hardship for patients to undergo recovery because their feelings and sensations are intensely outstanding. But just as this and the above studies imply, a large proportion of schizophrenics do not have self-awareness of their illness for many factors and severity of reasoning of their diagnoses.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is an illness that causes shifts in mood, energy, and ability to function. Self-awareness is crucial in those suffering from this disease, as they must be able to distinguish between feeling a certain way because of the disorder or because of separate issues. "Personality, behavior, and dysfunction affect your bipolar disorder, so you must 'know' yourself in order to make the distinction."[70] This disorder is a difficult one to diagnose, as self-awareness changes with mood. "For instance, what might appear to you as confidence and clever ideas for a new business venture might be a pattern of grandiose thinking and manic behavior".[71] Issues occur between understanding irrationality in a mood swing and being completely wrapped in a manic episode, rationalizing that the exhibited behaviors are normal.

It is important to be able to distinguish what are symptoms of bipolar disorder and what is not. A study done by Mathew et al. was done with the aim of "examining the perceptions of illness in self and among other patients with bipolar disorder in remission".[72]

The study took place at the Department of Psychiatry, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India, which is a centre that specializes in the "management of patients with mental and behavioural disorders".[72] Eighty two patients (thirty two female and fifty male) agreed to partake in the study. These patients met the "International Classification of Diseases – 10 diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder I or II and were in remission"[72] and were put through a variety of baseline assessments before beginning the study. These baseline assessments included using a vignette, which was then used as an assessment tool during their follow-up. Patients were then randomly divided into two groups, one who would be following a "structured educational intervention programme"[72] (experimental group), while the other would be following "usual care" (control group).

The study was based on an interview in which patients were asked an array of open-ended questions regarding topics such as "perceived causes, consequences, severity and its effects on body, emotion, social network and home life, and on work, severity, possible course of action, help-seeking behaviour and the role of the doctor/healer".[72] The McNemar test was then used to compare the patients perspective of the illness versus their explanation of the illness. The results of the study show that the beliefs that patients associated with their illness corresponds with the possible causes of the disorder,[72] whereas "studies done among patients during periods of active psychosis have recorded disagreement between their assessments of their own illness".[73] This ties in to how difficult self-awareness is within people who suffer from bipolar disorder.

Although this study was done on a population that were in remission from the disease, the distinction between patients during "active psychosis" versus those in remission shows the evolution of their self-awareness throughout their journey to recovery.

Plants

Self-discrimination in plants is found within their roots, tendrils and flowers that avoid themselves but not others in their environment.[74]

Self-incompatibility mechanism providing evidence for self-awareness in plants

Self-awareness in plants is a fringe topic in the field of self-awareness, and is researched predominantly by botanists. The claim that plants are capable of perceiving self lies in the evidence found that plants will not reproduce with themselves due to a gene selecting mechanism. In addition, vining plants have been shown to avoid coiling around themselves, due to chemical receptors in the plants' tendrils. Unique to plants, awareness of self means that the plant can recognise self, whereas all other known conceptions of self-awareness involve or are centered on the ability to recognise what is not self.[citation needed]

Recognition and rejection of self in plant reproduction

Research by June B. Nasrallah discovered that the plant's pollination mechanism also serves as a mechanism against self-reproduction, which lays out the foundation of scientific evidence that plants could be considered as self-aware organisms. The SI (Self-incompatibility) mechanism in plants is unique in the sense that awareness of self derives from the capacity to recognise self, rather than non-self. The SI mechanism function depends primarily on the interaction between genes S-locus receptor protein kinase (SRK) and S-locus cysteine-rich protein gene (SCR). In cases of self-pollination, SRK and SCR bind to activate SKR, Inhibiting pollen from fertilizing. In cases of cross-pollination, SRK and SCR do not bind and therefore SRK is not activated, causing the pollen to fertilise. In simple terms, the receptors either accept or reject the genes present in the pollen, and when the genes are from the same plant, the SI mechanism described above creates a reaction to prevent the pollen from fertilising.[citation needed]

Self-discrimination in the tendrils of the vine Cayratia japonica mediated by physiological connection

The research by Yuya Fukano and Akira Yamawo provides a link between self-discrimination in vining plants and amongst other classifications where the mechanism discovery has already been established. It also contributes to the general foundation of evidence of self-discrimination mechanisms in plants. The article makes the claim that the biological self-discrimination mechanism that is present in both flowering plants and ascidians, are also present in vining plants. They tested this hypothesis by doing touch tests with self neighbouring and non-self neighbouring pairs of plants. the test was performed by placing the sets of plants close enough for their tendrils to interact with one-another. Evidence of self-discrimination in above-ground plants is demonstrated in the results of the touch testing, which showed that in cases of connected self plants, severed self plants and non-self plants, the rate of tendril activity and likeliness to coil was higher among separated plants than those attached via rhizomes.[citation needed]

Theater

Theater also concerns itself with other awareness besides self-awareness. There is a possible correlation between the experience of the theater audience and individual self-awareness. As actors and audiences must not "break" the fourth wall in order to maintain context, so individuals must not be aware of the artificial, or the constructed perception of his or her reality. This suggests that both self-awareness and the social constructs applied to others are artificial continuums just as theater is. Theatrical efforts such as Six Characters in Search of an Author, or The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, construct yet another layer of the fourth wall, but they do not destroy the primary illusion.

Science fiction

In science fiction, self-awareness describes an essential human property that often (depending on the circumstances of the story) bestows personhood onto a non-human. If a computer, alien or other object is described as "self-aware", the reader may assume that it will be treated as a completely human character, with similar rights, capabilities and desires to a normal human being.[75] The words "sentience", "sapience" and "consciousness" are used in similar ways in science fiction.

Robotics

In order to be "self-aware", robots can use internal models to simulate their own actions.[76]

See also

References

- ↑ "self-awareness". September 15, 2023. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/self-awareness.

- ↑ Jabr, Ferris (2012). "Self-Awareness with a Simple Brain". Scientific American Mind 23 (5): 28–29. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1112-28.

- ↑ Oberman, L.; Ramachandran, V.S. (2009). "Reflections on the Mirror Neuron System: Their Evolutionary Functions Beyond Motor Representation". in Pineda, J.A.. Mirror Neuron Systems: The Role of Mirroring Processes in Social Cognition. Humana Press. pp. 39–62. ISBN 978-1-934115-34-3. https://archive.org/details/mirrorneuronsyst00pine.

- ↑ Ramachandran, V.S. (2009). "Self Awareness: The Last Frontier". https://www.edge.org/conversation/self-awareness-the-last-frontier.

- ↑ de Vignemont, Frédérique (2020-07-08). "Bodily Awareness". https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bodily-awareness/.

- ↑ Mehling, Wolf E.; Gopisetty, Viranjini; Daubenmier, Jennifer; Price, Cynthia J.; Hecht, Frederick M.; Stewart, Anita (19 May 2009). "Body Awareness: Construct and Self-Report Measures". PLOS ONE 4 (5): e5614. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005614. PMID 19440300. Bibcode: 2009PLoSO...4.5614M.

- ↑ Garfinkel, Paul E.; Moldofsky, Harvey; Garner, David M.; Stancer, Harvey C.; Coscina, Donald V. (1978). "Body Awareness in Anorexia Nervosa: Disturbances in 'Body Image' and 'Satiety'". Psychosomatic Medicine (Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health)) 40 (6): 487–498. doi:10.1097/00006842-197810000-00004. ISSN 0033-3174. PMID 734025.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Moore, Chris; Mealiea, Jennifer; Garon, Nancy; Povinelli, Daniel J. (1 March 2007). "The Development of Body Self-Awareness". Infancy 11 (2): 157–174. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00220.x.

- ↑ Brownell, Celia A.; Zerwas, Stephanie; Ramani, Geetha B. (September 2007). "'So Big': The Development of Body Self-Awareness in Toddlers". Child Development 78 (5): 1426–1440. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01075.x. PMID 17883440.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Plotnik, Joshua; Waal, Frans; Reiss, Diana (2006). "Self recognition in an Asian elephant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 103 (45): 17053–57. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608062103. PMID 17075063. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10317053P.

- ↑ Bekoff, M. (2002). "Animal reflections". Nature 419 (6904): 255. doi:10.1038/419255a. PMID 12239547.

- ↑ Bard, Kim (2006). "Self-Awareness in Human and Chimpanzee Infants: What Is Measured and What Is Meant by the Mark and Mirror Test?". Infancy 9 (2): 191–219. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0902_6.

- ↑ Gallup, Gordon G.; Anderson, James R.; Shillito, Daniel J. (2002). "The Mirror Test". in Bekoff, Marc; Allen, Colin; Burghardt, Gordon M.. The Cognitive Animal: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition. MIT Press. pp. 325–334. ISBN 978-0-262-52322-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=T-ztyW8eTnIC&pg=PA325.

- ↑ Tennesen, Michael (2003). "Do Dolphins Have a Sense of Self?". National Wildlife. World Edition. http://www.nwf.org/news-and-magazines/national-wildlife/animals/archives/2003/natural-inquiries-dolphin.aspx.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Prior, H.; Schwarz, A.; Güntürkün, O. (2008). "Mirror-Induced Behavior in the Magpie (Pica pica): Evidence of Self-Recognition". PLOS Biology 6 (8): e202. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060202. PMID 18715117.

- ↑ Alison, Motluk. "Mirror test shows magpies aren't so bird-brained". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn14552-mirror-test-shows-magpies-arent-so-bird-brained/. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ Degrazia, David (2009). "Self-awareness in animals". in Lurz, Robert W.. The Philosophy of Animal Minds. pp. 201–217. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511819001.012. ISBN 9780511819001. https://philosophy.columbian.gwu.edu/sites/philosophy.columbian.gwu.edu/files/image/degrazia_selfawarenessanimals.pdf. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ↑

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Rochat, Philippe (December 2003). "Five levels of self-awareness as they unfold early in life". Consciousness and Cognition 12 (4): 717–731. doi:10.1016/s1053-8100(03)00081-3. PMID 14656513.

- ↑ Duval, Shelley; Wicklund, Robert A. (1972). A Theory of Objective Self Awareness. Academic Press. ISBN 9780122256509. OCLC 643552644. https://archive.org/details/theoryofobjectiv0000duv.[page needed]

- ↑ Cohen, Anthony (2002). Self Consciousness: An Alternative Anthropology of Identity. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-41898-7.[page needed]

- ↑ Duval, Thomas Shelley; Silvia, Paul J. (2001). "Introduction & Overview". Self-Awareness & Causal Attribution. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1489-3_1. ISBN 978-1-4613-5579-3.

- ↑ Demetriou, Andreas; Kazi, Smaragda (February 2013). Unity and Modularity in the Mind and Self: Studies on the Relationships between Self-awareness, Personality, and Intellectual Development from Childhood to Adolescence. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69601-7.[page needed]

- ↑ Demetriou, Andreas; Kazi, Smaragda (May 2006). "Self-awareness in g (with processing efficiency and reasoning)". Intelligence 34 (3): 297–317. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.10.002.

- ↑ Cherry, Kendra (5 July 2019), Self Efficacy and Why Believing in Yourself Matters

- ↑ Geangu, Elena (March 2008). "Notes on self awareness development in early infancy". Cognitie, Creier, Comportament / Cognition, Brain, Behavior 12 (1): 103–113. ProQuest 201571751. http://www.devpsychology.ro/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/y4t7x_Geangu_ccc_mar2008.pdf.

- ↑ Bertenthal, Bennett I.; Fischer, Kurt W. (1978). "Development of self-recognition in the infant". Developmental Psychology 14 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.14.1.44.

- ↑ Couchman, Justin J. (January 2015). "Humans and monkeys distinguish between self-generated, opposing, and random actions". Animal Cognition 18 (1): 231–238. doi:10.1007/s10071-014-0792-6. PMID 25108418.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Integrative processes and socialization early to middle childhood. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 9780203767696.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Rochat, Philippe (23 October 1998). "Self-perception and action in infancy". Experimental Brain Research 123 (1–2): 102–109. doi:10.1007/s002210050550. PMID 9835398.

- ↑ Broesch, Tanya; Callaghan, Tara; Henrich, Joseph; Murphy, Christine; Rochat, Philippe (August 2011). "Cultural Variations in Children's Mirror Self-Recognition". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42 (6): 1018–1029. doi:10.1177/0022022110381114.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Filippetti, M. L.; Farroni, T.; Johnson, M. H. (May 2016). "Five-Month-old Infants' Discrimination of Visual-Tactile Synchronous Facial Stimulation: Brief Report". Infant and Child Development 25 (3): 317–322. doi:10.1002/icd.1977. http://repository.essex.ac.uk/26203/1/332.pdf.

- ↑ Zeanah, Charles (2009). Handbook of Infant Mental Health. New York: Guilford Press.

- ↑ Harter, Susan (1999). The Construction of the Self. Guilford Press. ISBN 9781572304321. https://archive.org/details/constructionofse00susa.

- ↑ Sandu, Cristina Marina; Pânişoarã, Georgeta; Pânişoarã, Ion Ovidiu (May 2015). "Study on the Development of Self-awareness in Teenagers". Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 1656–1660. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.060.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Moran, Orla; Almada, Priscilla; McHugh, Louise (January 2018). "An investigation into the relationship between the three selves (Self-as-Content, Self-as-Process, and Self-as-Context) and mental health in adolescents". Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 7: 55–62. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.01.002.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Mohammadiarya, Alireza; Sarabi, Salar Dousti; Shirazi, Mahmoud; Lachinani, Fatemeh; Roustaei, Amin; Abbasi, Zohre; Ghasemzadeh, Azizreza (2012). "The Effect of Training Self-Awareness and Anger Management on Aggression Level in Iranian Middle School Students". Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 46: 987–991. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.235.

- ↑

- Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm (1911). "Ecce Homo". in Levy, Oscar. The Complete Works. 17. p. 117.

- Schacht, Richard (1994). Nietzsche, Genealogy, Morality. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-08318-9.

- Wright, Willard Huntington (1915). "The Geneaology of Morals". What Nietzsche Taught. New York: B.W. Huebsch. pp. 209–10.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Nimbalkar, N. (2011). "John Locke on Personal identity". Mens Sana Monographs 9 (1): 268–275. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.77443. PMID 21694978.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Locke, John (1813). "Of Identity and Diversity". An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. 1. Boston: Cummings & Hillard.

- ↑ Goldstein, Abraham S. (1967). The Insanity Defense. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-300-00099-3. https://archive.org/details/insanitydefense00abra_0/page/n7/mode/2up.

- ↑ Xavier, Amador. "Anosognosia (Lack of Insight) Fact Sheet". http://www.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Mental_Illnesses/Schizophrenia9/Anosognosia_Fact_Sheet.htm.

- ↑ Prigatano, George P.. "Disorders of Behavior and Self-Awareness". http://www.thebarrow.org/Education_And_Resources/Barrow_Quarterly/204957.

- ↑ Leathem, Janet M.; Murphy, Latesha J.; Flett, Ross A. (August 9, 2010). "Self- and Informant-Ratings on the Patient Competency Rating Scale in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 20 (5): 694–705. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.5.694.1122. PMID 10079045.

- ↑ Prigatano, George P. (1999). "Diller lecture: Impaired awareness, finger tapping, and rehabilitation outcome after brain injury.". Rehabilitation Psychology 44 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.44.2.145.

- ↑ Prigatano, George P (December 2009). "Anosognosia: clinical and ethical considerations". Current Opinion in Neurology 22 (6): 606–611. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328332a1e7. PMID 19809315.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Heilman, K. M.; Barrett, A. M.; Adair, J. C. (29 November 1998). "Possible mechanisms of anosognosia: a defect in self–awareness". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 353 (1377): 1903–1909. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0342. PMID 9854262.

- ↑ Sack, M; Cassidy, JT; Bole, GG (December 1975). "Prognostic factors in polyarteritis". The Journal of Rheumatology 2 (4): 411–20. PMID 1533.

- ↑ Rubens, A. B. (1 July 1985). "Caloric stimulation and unilateral visual neglect". Neurology 35 (7): 1019–24. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.7.1019. PMID 4010940.

- ↑ National alliance on mental illness. "Mental illnesses". http://nami.org/template.cfm?section=By_Illness.

- ↑ "Dissociative Disorders". National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Dissociative-Disorders.

- ↑ Dryden-Edwards, Roxanne. "Dissociative Identity Disorder Symptoms and Treatments". in Conrad Stöppler, Melissa. https://www.medicinenet.com/dissociative_identity_disorder/article.htm#what_are_dissociative_identity_disorder_symptoms_and_signs.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Ramsland, Katherine; Kuter, Rachel. "Multiple Personalities: Crime and Defense". http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/psychology/multiples/3.html.

- ↑ Dryden-Edwards, Roxanne. "Dissociative Identity Disorder". http://www.medicinenet.com/dissociative_identity_disorder/article.htm.

- ↑ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. "Autism Fact Sheet". Office of Communications and Public Liaison. http://ninds.nih.gov/disorders/autism/detail_autism.htm.

- ↑ "Autistic disorder". http://www.autismspeaks.org/what-autism.

- ↑ "Recognizing Autism Spectrum Disorder". http://www.autism.org.uk/working-with/health/information-for-general-practitioners/recognising-autism-spectrum-disorder.

- ↑ Sarita, Freedman, PhD. "Self-Awareness and Self-Acceptance in School-Age Students with ASD". 2014 Autism Asperger's Digest. AADigest is a division of Future Horizons. http://autismdigest.com/self-awareness-and-self-acceptance-in-school-age-students-with-asd/.

- ↑ McGeer, Victoria (2004). "Autistic Self-Awareness". Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 11 (3): 235–251. doi:10.1353/ppp.2004.0066.

- ↑ Lombardo, M. V.; Chakrabarti, B.; Bullmore, E. T.; Sadek, S. A.; Pasco, G.; Wheelwright, S. J.; Suckling, J.; Baron-Cohen, S. (1 February 2010). "Atypical neural self-representation in autism". Brain 133 (2): 611–624. doi:10.1093/brain/AWP306. PMID 20008375.

- "How the autistic brain distinguishes oneself from others". ScienceDaily (Press release). December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Uddin, Lucina Q.; Davies, Mari S.; Scott, Ashley A.; Zaidel, Eran; Bookheimer, Susan Y.; Iacoboni, Marco; Dapretto, Mirella (29 October 2008). "Neural Basis of Self and Other Representation in Autism: An fMRI Study of Self-Face Recognition". PLOS ONE 3 (10): e3526. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003526. PMID 18958161. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.3526U.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Uddin, Lucina Q. (June 2011). "The self in autism: An emerging view from neuroimaging". Neurocase 17 (3): 201–208. doi:10.1080/13554794.2010.509320. PMID 21207316.

- ↑ Jackson, Paul; Skirrow, Paul; Hare, Dougal Julian (May 2012). "Asperger Through the Looking Glass: An Exploratory Study of Self-Understanding in People with Asperger's Syndrome". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (5): 697–706. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1296-8. PMID 21647793.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "University of Pennsylvania". http://legacy.uphs.upenn.edu.

- ↑ O'Donovan, M. C.; Williams, N. M.; Owen, M. J. (15 October 2003). "Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia". Human Molecular Genetics 12 (suppl 2): R125–R133. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302. PMID 12952866.

- ↑ Day, R. (August 1981). "Life events and schizophrenia: The "triggering" hypothesis". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 64 (2): 97–122. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00765.x. PMID 7032227.

- ↑ Medalia, Alice; Lim, Rosa W. (December 2004). "Self-awareness of cognitive functioning in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research 71 (2–3): 331–338. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.003. PMID 15474903.

- ↑ Amador, XF; Strauss, DH; Yale, SA; Flaum, MM; Endicott, J; Gorman, JM (June 1993). "Assessment of insight in psychosis". American Journal of Psychiatry 150 (6): 873–879. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.6.873. PMID 8494061.

- ↑ Bedford, Nicholas J.; David, Anthony S. (January 2014). "Denial of illness in schizophrenia as a disturbance of self-reflection, self-perception and insight". Schizophrenia Research 152 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.006. PMID 23890596.

- ↑ "Self Awareness". Bipolar Insights. http://bipolarinsights.com/?page_id=247.

- ↑ Tartakovsky, Margarita (2016-05-17). "Living with Bipolar Disorder". http://psychcentral.com/lib/living-with-bipolar-disorder/0001851.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 72.4 72.5 Mathew, Anandit J.; Samuel, Beulah; Jacob, K.S. (September 2010). "Perceptions of Illness in Self and in Others Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder". International Journal of Social Psychiatry 56 (5): 462–470. doi:10.1177/0020764009106621. PMID 19651694.

- ↑ McEvoy, JP; Schooler, NR; Friedman, E; Steingard, S; Allen, M (November 1993). "Use of psychopathology vignettes by patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and by mental health professionals to judge patients' insight". American Journal of Psychiatry 150 (11): 1649–1653. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.11.1649. PMID 8214172.

- ↑ Fukano, Yuya; Yamawo, Akira (7 September 2015). "Self-discrimination in the tendrils of the vine Cayratia japonica is mediated by physiological connection". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282 (1814): 20151379. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.1379. PMID 26311669.

- ↑ Robert Kolker Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, p. 106, Oxford University Press US, 2006 ISBN:978-0-19-517452-6

- ↑ Winfield, Alan F. T. (2014). "Robots with Internal Models: A Route to Self-Aware and Hence Safer Robots". The Computer After Me. pp. 237–252. doi:10.1142/9781783264186_0016. ISBN 978-1-78326-417-9. http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/24467/1/Winfield_Chapter_in_ComputerAfterMe_finaldraft.pdf.

External links

- Ashley, Greg; Reiter-Palmon, Roni (1 September 2012). "Self-Awareness and the Evolution of Leaders: The Need for a Better Measure of Self-Awareness". Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 14 (1): 2–17. doi:10.21818/001c.17902. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub/7/.

- Mograbi, D. C., Hall, S., Arantes, B., & Huntley, J. (2023). The cognitive neuroscience of self‐awareness: Current framework, clinical implications, and future research directions. WIREs Cognitive Science, e1670. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1670

|