Biology:Laccase

Laccases (EC 1.10.3.2) are multicopper oxidases found in plants, fungi, and bacteria. Laccases oxidize a variety of phenolic substrates, performing one-electron oxidations, leading to crosslinking. For example, laccases play a role in the formation of lignin by promoting the oxidative coupling of monolignols, a family of naturally occurring phenols.[1] Other laccases, such as those produced by the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus, play a role in the degradation of lignin, and can therefore be classed as lignin-modifying enzymes.[2] Other laccases produced by fungi can facilitate the biosynthesis of melanin pigments.[3] Laccases catalyze ring cleavage of aromatic compounds.[4]

Laccase was first studied by Hikorokuro Yoshida in 1883 and then by Gabriel Bertrand[5] in 1894[6] in the sap of the Japanese lacquer tree, where it helps to form lacquer, hence the name laccase.

Active site

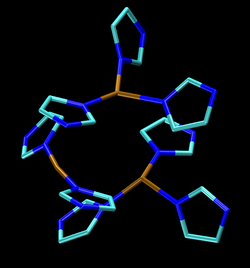

The active site consists of four copper centers, which adopt structures classified as type I, type II, and type III. A tricopper ensemble contains types II and III copper (see figure). It is this center that binds O2 and reduces it to water. Each Cu(I,II) couple delivers one electron required for this conversion. The type I copper does not bind O2, but functions solely as an electron transfer site. The type I copper center consists of a single copper atom that is ligated to a minimum of two histidine residues and a single cysteine residue, but in some laccases produced by certain plants and bacteria, the type I copper center contains an additional methionine ligand. The type III copper center consists of two copper atoms that each possess three histidine ligands and are linked to one another via a hydroxide bridging ligand. The final copper center is the type II copper center, which has two histidine ligands and a hydroxide ligand. The type II together with the type III copper center forms the tricopper ensemble, which is where dioxygen reduction takes place.[7] The type III copper can be replaced by Hg(II), which causes a decrease in laccase activity.[1] Cyanide removes all copper from the enzyme, and re-embedding with type I and type II copper has been shown to be impossible. Type III copper, however, can be re-embedded back into the enzyme. A variety of other anions inhibit laccase.[8]

Laccases affects the oxygen reduction reaction at low overpotentials. The enzyme has been examined as the cathode in enzymatic biofuel cells.[9] They can be paired with an electron mediator to facilitate electron transfer to a solid electrode wire.[10] Laccases are some of the few oxidoreductases commercialized as industrial catalysts.

Activity in wheat dough

Laccases have the potential to crosslink food polymers such as proteins and nonstarch polysaccharides in dough. In non-starch polysaccharides, such as arabinoxylans (AX), laccase catalyzes the oxidative gelation of feruloylated arabinoxylans by dimerization of their ferulic esters.[11] These cross-links have been found to greatly increase the maximum resistance and decrease extensibility of the dough. The resistance was increased due to the crosslinking of AX via ferulic acid and resulting in a strong AX and gluten network. Although laccase is known to crosslink AX, under the microscope it was found that the laccase also acted on the flour proteins. Oxidation of the ferulic acid on AX to form ferulic acid radicals increased the oxidation rate of free SH groups on the gluten proteins and thus influenced the formation of S-S bonds between gluten polymers.[12] Laccase is also able to oxidize peptide-bound tyrosine, but very poorly.[12] Because of the increased strength of the dough, it showed irregular bubble formation during proofing. This was a result of the gas (carbon dioxide) becoming trapped within the crust so it could not diffuse out (like it would have normally) and causing abnormal pore size.[11] Resistance and extensibility was a function of dosage, but at very high dosage the dough showed contradictory results: maximum resistance was reduced drastically. The high dosage may have caused extreme changes in the structure of dough, resulting in incomplete gluten formation. Another reason is that it may mimic overmixing, causing negative effects on gluten structure. Laccase-treated dough had low stability over prolonged storage. The dough became softer and this is related to laccase mediation. The laccase-mediated radical mechanism creates secondary reactions of FA-derived radicals that result in breaking of covalent linkages in AX and weakening of the AX gel.[11]

Biotechnology

The ability of laccases to degrade various aromatic polymers has led to research into their potential for bioremediation and other industrial applications. Laccases have been applied in the production of wines[13] as well as in the food industry.[14][15] Studies utilizing fungal and bacterial laccases to degrade emerging pollutants have also been conducted.[16][17] In particular, it has been shown that laccases can be applied to catalyze the degradation and detoxification a large range of aromatic contaminants,[18] including azo dyes,[19][20] bisphenol A[21] and pharmaceuticals.[22] Transgenic plants whose roots secrete it could also be used in the same way.[23][24]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Multicopper Oxidases and Oxygenases". Chemical Reviews 96 (7): 2563–2606. November 1996. doi:10.1021/cr950046o. PMID 11848837.

- ↑ "Biotechnological applications and potential of wood-degrading mushrooms of the genus Pleurotus". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 58 (5): 582–594. April 2002. doi:10.1007/s00253-002-0930-y. PMID 11956739.

- ↑ "Unraveling Melanin Biosynthesis and Signaling Networks in Cryptococcus neoformans". mBio 10 (5): e02267-19. October 2019. doi:10.1128/mBio.02267-19. PMID 31575776.

- ↑ "Laccases: structure, reactions, distribution". Micron 35 (1–2): 93–96. 2004. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2003.10.029. PMID 15036303.

- ↑ "Gabriel Bertrand on isimabomba" (in fr). http://isimabomba.free.fr/biographies/chimistes/bertrand.htm.

- ↑ Science and civilisation in China: Chemistry and chemical. 5. Cambridge University Press. 1980-09-25. p. 209. ISBN 9780521085731. https://books.google.com/books?id=xrNDwP0pS8sC&pg=PA209.

- ↑ "Electron transfer and reaction mechanism of laccases". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 72 (5): 869–883. March 2015. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1826-6. PMID 25572295.

- ↑ "Laccases: Biological functions, molecular structure and industrial applications.". Industrial Enzymes. Springer. 2007. pp. 461–476. doi:10.1007/1-4020-5377-0_26. ISBN 978-1-4020-5376-4.

- ↑ "Direct, Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction by Laccase on Anthracene-2-methanethiol Modified Gold". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 1 (15): 2251–2254. August 2010. doi:10.1021/jz100745s. PMID 20847902.

- ↑ "Bioelectrocatalytic hydrogels from electron-conducting metallopolypeptides coassembled with bifunctional enzymatic building blocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (40): 15275–15280. October 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805249105. PMID 18824691. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10515275W.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tyrosinase and laccase as novel crosslinking tools for food biopolymers.. VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. October 2008. ISBN 978-951-38-7118-5. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/3018.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Elucidating the mechanism of laccase and tyrosinase in wheat bread making". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55 (15): 6357–6365. July 2007. doi:10.1021/jf0703349. PMID 17602567.

- ↑ "Phenols Removal in Musts: Strategy for Wine Stabilization by Laccase". J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 45 (3): 102–107. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2006.12.004.

- ↑ "Laccases in Food Industry: Bioprocessing, Potential Industrial and Biotechnological Applications". Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8 (8): 222. 2020. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00222. PMID 32266246.

- ↑ "Uses of laccases in the food industry". Enzyme Research 2010: 918761. September 2010. doi:10.4061/2010/918761. PMID 21048873.

- ↑ "Linking Enzymatic Oxidative Degradation of Lignin to Organics Detoxification". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19 (11): 3373. October 2018. doi:10.3390/ijms19113373. PMID 30373305.

- ↑ "Laccases to take on the challenge of emerging organic contaminants in wastewater". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98 (24): 9931–9952. December 2014. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-6177-6. PMID 25359481. http://doc.rero.ch/record/326346/files/253_2014_Article_6177.pdf.

- ↑ "Novel thermophilic bacterial laccase for the degradation of aromatic organic pollutants". Front. Chem. 9: 711345. 2021. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.711345. PMID 34746090. Bibcode: 2021FrCh....9..880S.

- ↑ "Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Bacterial Laccase and Improvement of Its Efficiency by Directed Evolution on Dye Degradation". Frontiers in Microbiology 12: 633004. 2021. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.633004. PMID 34054745.

- ↑ "Characterisation and optimisation of a novel laccase from Sulfitobacter indolifex for the decolourisation of organic dyes". International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 190: 574–584. November 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.003. PMID 34506861.

- ↑ "A promising laccase immobilization approach for Bisphenol A removal from aqueous solutions". Bioresource Technology 271: 360–367. January 2019. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.09.129. PMID 30293031.

- ↑ "Degradation of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by White-Rot Fungi—a Critical Review". Current Pollution Reports 3 (2): 88–103. 2017. doi:10.1007/s40726-017-0049-5. https://ro.uow.edu.au/eispapers/6332.

- ↑ Singh Arora, Daljit; Kumar Sharma, Rakesh (2009-06-10). "Ligninolytic Fungal Laccases and Their Biotechnological Applications". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (Springer) 160 (6): 1760–1788. doi:10.1007/s12010-009-8676-y. ISSN 0273-2289. PMID 19513857.

- ↑ Tschofen, Marc; Knopp, Dietmar; Hood, Elizabeth; Stöger, Eva (2016-06-12). "Plant Molecular Farming: Much More than Medicines". Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry (Annual Reviews) 9 (1): 271–294. doi:10.1146/annurev-anchem-071015-041706. ISSN 1936-1327. PMID 27049632. Bibcode: 2016ARAC....9..271T.

General sources

- "Laccases for Denim Bleaching: An Eco-Friendly Alternative". Open Textile Journal 5 (1): 1–7. February 2012. doi:10.2174/1876520301205010001.

- "An in silico [correction of insilico] approach to bioremediation: laccase as a case study". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling 26 (5): 845–849. January 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2007.05.005. PMID 17606396.

- Xu, Feng (Spring 2005). "Applications of oxidoreductases: Recent progress". Industrial Biotechnology (Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.) 1 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1089/ind.2005.1.38. ISSN 1931-8421.

External links

- BRENDA

- Laccase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

|