Earth:Watershed delineation

Watershed delineation is the process of identifying the boundary of a watershed, also referred to as a catchment, drainage basin, or river basin. It is an important step in many areas of environmental science, engineering, and management, for example to study flooding, aquatic habitat, or water pollution.

The activity of watershed delineation is typically performed by geographers, scientists, and engineers. Historically, watershed delineation was done by hand on paper topographic maps, sometimes supplemented with field research. In the 1980s, automated methods were developed for watershed delineation with computers and electronic data, and these are now in widespread use.

Computerized methods for watershed delineation use digital elevation models (DEMs), datasets that represent the height of the earth's land surface. Computerized watershed delineation may be done using specialized hydrologic modeling software such as WMS, Geographic Information System software like ArcGIS or QGIS, or with programming languages like Python or R.

Watersheds are a fundamental geographic unit in hydrology, the science concerned with the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth. Delineating watersheds may be considered an application of hydrography, the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers. It is also related to geomorphometry, the quantitative science of analyzing land surfaces. Watershed delineation continues to be an active area of research, with scientists and programmers developing new algorithms and methods, and making use of increasingly high-resolution data from aerial or satellite remote sensing.

Manual watershed delineation

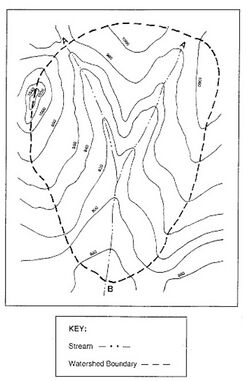

The conventional method of finding a watershed boundary is to draw it by hand on a paper topographic map, or on a transparent overlay. The watershed area can then be estimated using a planimeter, by overlaying graph paper and counting grid cells, or the result can be digitized for use with mapping software. The same process can be done on a computer, sketching the watershed boundary (with a mouse or stylus) over a digital copy of a topographic map.[1] This is referred to as "heads up digitizing" or "on-screen digitizing."[2]

For "manual" watershed delination, one must know how to read and interpret a topographic map, for example to identify ridges, valleys, and the direction of steepest slope.[3] Even in the computer era, manual watershed delineation is still a useful skill, in order to check whether watersheds generated with software are correct.[1]

Instructions for manual watershed delineation can be found in some textbooks in geography or environmental management, in government pamphlets,[4][5] or in online video tutorials.[6]

According to the US Geological Survey, there are 5 steps to manual watershed delineation:[6]

- Find the point of interest along a stream on the map. This is the "watershed outlet" or "pour point."

- Imagine or draw surface water flow lines that point downhill perpendicular to the topographic contours (this is the steepest direction).

- Mark the location of topographical high points (peaks) around the stream.

- Mark the points along contours that divide flows towards or away from the stream (ridges).

- Connect the dots to delineate the watershed.

General Rules:

- The watershed boundary should be perpendicular to contour lines where it crosses them.

- The watershed boundary must not cross rivers or streams other than at the outlet. (In some cases, a blue line representing a man-made canal or pipeline may traverse your watershed boundary.)

- The watershed boundary should run along ridgelines and connect high points.

One disadvantage to manual watershed delineation is that it is subject to errors and the individual judgment of the analyst. The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency wrote, "bear in mind that delineating a watershed is an inexact science. Any two people, even if both are experts, will come up with slightly different boundaries."[5]

Especially for smaller watersheds and when accurate results are important, field reconnaissance may be needed to find features that are not shown on maps. "Going out into the field allows you to identify human alterations, such as road ditches, storm sewers and culverts that could change the direction of waters flow and thus change the watershed boundaries."[5]

Automated or computerized watershed delineation

Using computer software to delineate watersheds can be much faster than manual methods. It may also be more consistent, as it removes analyst's subjectivity. Automatic methods of watershed delineation have been in use since the 1980s, and are now in widespread use in the science and engineering communities. Researchers have even used computer methods to delineate watersheds on Mars.[7][8]

Automated watershed delineation methods use digital data of the earth's elevation, a Digital Elevation Model, or DEM. Typically, algorithms use the method of "steepest slope" to calculate the flow direction from a grid cell (or pixel) to one of its neighbors.[9]

It is possible to use DEMs in different formats for watershed delineation, such as a Triangular Irregular Network (TIN),[10] or Hexagonal tiling[11] however most contemporary algorithms make use of a regular rectangular grid.[12] In the 1980s and 1990s, digital elevation models were often obtained by scanning and digitizing the contours on paper topographic maps, which were then converted to a TIN or a gridded DEM.[13] More recently, the DEM is obtained by aerial or satellite remote sensing, using stereophotogrammetry, lidar, or radar.[14]

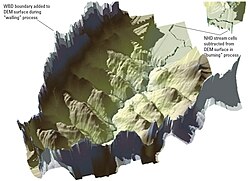

To use a rectangular grid DEM for watershed delineation, it must first be processed or "conditioned" in order to return realistic results.[9] The result is sometimes referred to as a "hydro-enforced" DEM or a "HydroDEM." Most of the software packages listed below can perform these functions on a "raw" DEM, or analysts can download hydrologically-conditioned DEMs such as the near-global HydroSHEDS,[15] MERIT-Hydro,[16] or EDNA [17] for the continental United States. The usual steps for hydrologic conditioning of a DEM are:

- Fill sinks.

- "Burn in" the stream channels.

- Calculate flow direction.

- Calculate flow accumulation.

Additionally, some methods allow for "fencing ridgelines" and burning in flow pathways through lakes.[18] Some methods also enforce a small slope onto flat areas so that flow will continue to move toward the outlet.[19] The step of "burning in" stream channels involves artificially deepening the channel, by subtracting a large elevation value from pixels that represent the channel. This ensures that once flow has entered the channel, it will stay there rather than jumping out and flowing overland or into another channel. Some algorithms infer the location of channels automatically from the DEM. Better results are usually obtained by burning in mapped stream channels, or channels derived from satellite or aerial imagery.[20]

There are several different algorithms available for calculating flow direction from a DEM. The first method, introduced by Australian geographers O'Callaghan and Mark in 1984, is referred to as D8.[12] Water flows from a pixel to one of 8 possible directions to a neighboring cell (including diagonally), based on the direction of steepest slope. There are disadvantages to this method as water flow is limited to 8 directions, separated by 45°, which may result in unrealistic flow patterns. Also, because all of the flow is routed in one direction, the D8 method is unable to model situations where the flow diverges, such as on convex hillsides, in a river delta, or in branched or braided rivers. Alternative algorithms have been proposed and implemented to overcome this limitation, such as D∞.[21] Nevertheless, the D8 algorithm remains in widespread use, and has been used to create important datasets such as HydroBasins [15] and MERIT-Basins.[16]

Computerized watershed delineation is not always correct. Some errors stem from incorrectly placing the watershed outlet on the digital river network, or "snapping the pour point."[22] Another class of errors stems from inaccuracies in the digital terrain data, or where its resolution is too coarse to capture flow pathways.[2] In general, DEMs with higher spatial resolution can more realistically describe topography of the land surface and flow direction. However, there is a tradeoff, as a finer grid with more pixels increases computing time.[16] Nevertheless, even high-resolution data may not adequately capture flow pathways in complex environments like cities and suburbs, where flow is directed by curbs, culverts, and storm drains.[23] Finally, some errors can result from the algorithm or the choice of parameters.[24]

Because errors are common, some authorities insist that the results of automated delineation must be carefully checked. The US Geological Survey's standards for the US Watershed Boundary Dataset allow the use of software "to generate intermediate or “draft” boundary lines," which then must be verified by the analyst by overlaying them on a computer display over basemaps (scanned topographic maps, aerial photographs) to verify their accuracy.[1]

Software for watershed delineation

Some of the first watershed delineation software was written in FORTRAN, such as CATCH [25] and DEDNM.[19] Watershed delineation tools are a part of several Geographic Information System software packages such as ArcGIS, QGIS, and GRASS GIS. There are standalone programs for watershed delineation such as TauDEM. Watershed delineation tools are also incorporated into some hydrologic modeling software packages.

Software developers have also published libraries or modules in several languages (see list below). Many of these packages are free and open source, which means they can be expanded or adapted by those willing and able to write or modify code. Finally, there are web applications for delineating watersheds. Some of these web apps have extra features for science and engineering like calculating flow statistics or watershed land cover types (e.g.: StreamStats, Model My Watershed).

Standalone watershed delineation software

- TauDEM,[26] Toolbox for ArcGIS, or command line executable for Windows.

- TOPAZ,[27] from the US Department of Agriculture, Windows executable.

Hydrologic Modeling Software with Watershed Delineation Capability

- WMS (hydrology software)

- SWAT model

- BASINS[28]

- BasinMaker,[29] for use with the RAVEN software suite, for parts of US and Canada only

- WEAP Model

GIS-based software

- ESRI ArcGIS or the ArcGIS online web application

- GRASS GIS, modules r.water, r.watershed, and r.stream

- QGIS

- SAGA GIS

- Whitebox Geospatial Analysis Tools

- ILWIS

- TerrSet (formerly IDRISI)

- TNTmips

- MapWindow GIS

- Manifold System

- Blue Marble Geographics § Global Mapper

Web Applications

- Global Watersheds,[30] web app and API

- Stream Stats,[31] from the US Geological Survey, allows you to delineate watersheds in the US only

- Model My Watershed,[32] by the Stroud Water Research Center, US only, can delineate watersheds based on an outlet point, and perform analyses related to water quality

- Ontario Watershed Information Tool,[33] for the province of Ontario in Canada

Vector datasets of pre-delineated watersheds

There are a number of vector datasets representing watersheds as polygons that can be displayed and analyzed with GIS or other software. In these datasets, the entire land surface is divided into "subwatersheds" or "unit catchments." Individual unit watersheds can be combined or merged to find larger watersheds. The unit catchments have linked hydrological code data or similar metadata to create a flow network, so flow pathways and connections can be determined via network analysis.[34]

This list is non-exhaustive, as many organizations and territories have produced their own watershed map data and have published via the web. Notable datasets include:

- United States Watershed Boundary Dataset,[35] website (continually updated)

- Canadian National Hydrographic Network Watershed Boundaries,[36] website

- HydroBasins [37] website (global, 2013)

- Hydrologic Derivatives for Modeling and Applications (HDMA),[38][39] (global, 2017)

- MERIT-Basins,[40][41] website (global, 2021)

- Hydrography90m,[42] website (2022, global, shows smaller headwater streams)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Federal guidelines, requirements, and procedures for the national Watershed Boundary Dataset. U.S. Geological Survey. 2009. https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/11/a3/pdf/tm11-a3_1ed.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Maceyka, Andy; Hansen, William F (2016). "Enhancing hydrologic mapping using LIDAR and high resolution aerial photos on the Francis Marion National Forest in coastal South Carolina". North Charleston, South Carolina: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. pp. 302. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs211/gtr_srs211_012.pdf.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey (2020-07-22). "To delineate a watershed you must identify land surface features from topographic contours". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTO3lRfpKVs. Retrieved 2023-02-07.

- ↑ USDA (n.d.), How to Read a Topographic Map and Delineate a Watershed, US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, https://bwsr.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2020-05/MN_Watershed_Delineation.pdf, retrieved 2023-02-07

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. "Determining Your Lake's Watershed". http://www.epa.state.il.us/water/conservation/lake-notes/determining-watershed.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 U.S. Geological Survey (July 22, 2020). "Manual watershed delineation is a five-step process". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IediKgLNMXA&t.

- ↑ Jenson, Susan K. (1991). "Applications of hydrologic information automatically extracted from digital elevation models". Hydrological Processes 5 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1002/hyp.3360050104. ISSN 1099-1085. Bibcode: 1991HyPr....5...31J. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hyp.3360050104. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ↑ Mest, Scott C.; Crown, David A.; Harbert, William (2010-09-01). "Watershed modeling in the Tyrrhena Terra region of Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research 115 (E9): –09001. doi:10.1029/2009JE003429. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 2010JGRE..115.9001M. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1029/2009JE003429. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Maidment, David R.; Djokic, Dean (2000). Hydrologic and Hydraulic Modeling Support: With Geographic Information Systems. ESRI, Inc.. ISBN 978-1-879102-80-4.

- ↑ Jones, Norman L.; Wright, Stephen G.; Maidment, David R. (1990-10-01). "Watershed Delineation with Triangle‐Based Terrain Models". Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 116 (10): 1232–1251. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1990)116:10(1232). ISSN 0733-9429. https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%290733-9429%281990%29116%3A10%281232%29. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- ↑ Liao, Chang; Tesfa, Teklu; Duan, Zhuoran; Leung, L. Ruby (2020-06-01). "Watershed delineation on a hexagonal mesh grid". Environmental Modelling & Software 128: 104702. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2020.104702. ISSN 1364-8152. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364815219308278. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 O'Callaghan, John F.; Mark, David M. (December 1984). "The extraction of drainage networks from digital elevation data". Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing 28 (3): 323–344. doi:10.1016/S0734-189X(84)80011-0.

- ↑ Wiche, Gregg J.; Jenson, S. K.; Baglio, J. V.; Domingue, Julia O. (1990). "Application of digital elevation models to delineate drainage areas and compute hydrologic characteristics for sites in the James River Basin, North Dakota". US Geological Survey. pp. 30. https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/2383/report.pdf.

- ↑ Li, Zhilin; Zhu, Christopher; Gold, Chris (2004). Digital terrain modeling: principles and methodology. CRC press. p. Chapter 3. ISBN 978-0-429-20507-1.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Lehner, Bernhard; Verdin, Kristine; Jarvis, Andy (2008). "New Global Hydrography Derived From Spaceborne Elevation Data". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 89 (10): 93–94. doi:10.1029/2008EO100001. ISSN 2324-9250. Bibcode: 2008EOSTr..89...93L. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008EO100001. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Yamazaki, D.; Oki, T.; Kanae, S. (2009-11-26). "Deriving a global river network map and its sub-grid topographic characteristics from a fine-resolution flow direction map". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 13 (11): 2241–2251. doi:10.5194/hess-13-2241-2009. ISSN 1607-7938. Bibcode: 2009HESS...13.2241Y. https://hess.copernicus.org/articles/13/2241/2009/. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ↑ Earth Resources Observation And Science (EROS) Center (2017), Elevation Derivatives for National Applications (EDNA) Seamless Three-Dimensional Hydrologic Database, U.S. Geological Survey, https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-elevation-derivatives-national-applications, retrieved 2023-02-21

- ↑ Maidment, David R.; Djokic, Dean (2000). Hydrologic and Hydraulic Modeling Support: With Geographic Information Systems. ESRI, Inc.. ISBN 978-1-879102-80-4.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Martz, L.W.; Garbrecht, J. (July 1992). "Numerical definition of drainage network and subcatchment areas from Digital Elevation Models". Computers & Geosciences 18 (6): 747–761. doi:10.1016/0098-3004(92)90007-E. ISSN 0098-3004. Bibcode: 1992CG.....18..747M. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/009830049290007E. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

- ↑ Lindsay, John B. (2016). "The practice of DEM stream burning revisited". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 41 (5): 658–668. doi:10.1002/esp.3888. ISSN 1096-9837. Bibcode: 2016ESPL...41..658L. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/esp.3888. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- ↑ Tarboton, David G. (February 1997). "A new method for the determination of flow directions and upslope areas in grid digital elevation models". Water Resources Research 33 (2): 309–319. doi:10.1029/96WR03137. Bibcode: 1997WRR....33..309T.

- ↑ Jenson, Susan K.; Domingue, Julia O. (1988). "Extracting topographic structure from digital elevation data for geographic information system analysis". Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 54 (11): 1593–1600. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=06a20725ae38b4dce81951bbb230b197dd346daa.

- ↑ Kayembe, Aimé; Mitchell, Carl P. J. (2018). "Determination of subcatchment and watershed boundaries in a complex and highly urbanized landscape". Hydrological Processes 32 (18): 2845–2855. doi:10.1002/hyp.13229. ISSN 1099-1085. Bibcode: 2018HyPr...32.2845K. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hyp.13229. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ Datta, Srijon; Karmakar, Shyamal; Mezbahuddin, Symon; Hossain, Mohammad Mozaffar; Chaudhary, B. S.; Hoque, Md. Enamul; Abdullah Al Mamun, M. M.; Baul, Tarit Kumar (2022-07-15). "The limits of watershed delineation: implications of different DEMs, DEM resolutions, and area threshold values". Hydrology Research 53 (8): 1047–1062. doi:10.2166/nh.2022.126. ISSN 0029-1277. https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2022.126. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ↑ Martz, Lawrence W.; Jong, Eeltje de (January 1988). "CATCH: A FORTRAN program for measuring catchment area from digital elevation models". Computers & Geosciences 14 (5): 627–640. doi:10.1016/0098-3004(88)90018-0. ISSN 0098-3004. Bibcode: 1988CG.....14..627M. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0098300488900180. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ↑ David Tarbotton (2016), Terrain Analysis Using Digital Elevation Models (TauDEM), Utah State University, Hydrology Research Group, https://hydrology.usu.edu/taudem/taudem5/, retrieved 2023-02-21

- ↑ USDA (1999), TOPAZ, United States Department of Agriculture, https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/30700510/TOPAZ_Table-of-Contents3.pdf, retrieved 2023-02-21

- ↑ US EPA (2015-07-23), Better Assessment Science Integrating Point and Non-point Sources (BASINS), United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, https://www.epa.gov/ceam/better-assessment-science-integrating-point-and-non-point-sources-basins, retrieved 2023-02-21

- ↑ M. Han; H. Shen; B. A. Tolson; J. R. Craig; J. Mai; S. Lin; N. B. Basu; F. Awol (2023), BasinMaker 3.0: a GIS toolbox for distributed watershed delineation of complex lake-river routing networks, University of Waterloo, http://hydrology.uwaterloo.ca/basinmaker/index.html, retrieved 2023-02-21

- ↑ Heberger, Matthew (2023). "Global Watersheds App". mghydro.com. https://mghydro.com/watersheds. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ↑ "StreamStats". U.S. Geological Survey. 2021. https://streamstats.usgs.gov/ss/. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ↑ Stroud Water Research Center (2023). "Model My Watershed". WikiWatershed. https://modelmywatershed.org/draw. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ↑ "Ontario Watershed Information Tool (OWIT) | ontario.ca". Government of Ontario. 2022. http://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-watershed-information-tool-owit. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ↑ Lehner, Bernhard (2014), HydroBASINS Technical Documentation Version 1.c, McGill University, https://data.hydrosheds.org/file/technical-documentation/HydroBASINS_TechDoc_v1c.pdf, retrieved 2023-02-16

- ↑ "Watershed Boundary Dataset". U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/national-hydrography/watershed-boundary-dataset. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ↑ Natural Resources Canada (2018-09-10). "National Hydrographic Network". https://natural-resources.canada.ca/science-and-data/science-and-research/earth-sciences/geography/topographic-information/geobase-surface-water-program-geeau/national-hydrographic-network/21361. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ↑ Lehner, Bernhard; Grill, Günther (2013). "Global river hydrography and network routing: baseline data and new approaches to study the world's large river systems". Hydrological Processes 27 (15): 2171–2186. doi:10.1002/2017GL072874.

- ↑ Verdin, Kristine L. (2017). "Hydrologic Derivatives for Modeling and Analysis—A new global high-resolution database". Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 24. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/ds1053. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- ↑ Verdin, Kristine L. (2017), Hydrologic Derivatives for Modeling and Applications (HDMA) Data, U.S. Geological Survey, https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/5910def6e4b0e541a03ac98c, retrieved 2023-03-02

- ↑ Lin, Peirong; Pan, Ming; Beck, Hylke E.; Yang, Yuan; Yamazaki, Dai; Frasson, Renato; David, Cédric H.; Durand, Michael et al. (2019). "Global Reconstruction of Naturalized River Flows at 2.94 Million Reaches". Water Resources Research 55 (8): 6499–6516. doi:10.1029/2019WR025287. PMID 31762499. Bibcode: 2019WRR....55.6499L.

- ↑ Yamazaki, Dai; Ikeshima, Daiki; Sosa, Jeison; Bates, Paul D.; Allen, George H.; Pavelsky, Tamlin M. (201). "MERIT Hydro: A High‐Resolution Global Hydrography Map Based on Latest Topography Dataset". Water Resources Research 55 (6): 5053–5073. doi:10.1029/2019WR024873. Bibcode: 2019WRR....55.5053Y. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2019WR024873. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ↑ Amatulli, Giuseppe; Garcia Marquez, Jaime; Sethi, Tushar; Kiesel, Jens; Grigoropoulou, Afroditi; Üblacker, Maria M.; Shen, Longzhu Q.; Domisch, Sami (2022-10-17). "Hydrography90m: a new high-resolution global hydrographic dataset". Earth System Science Data 14 (10): 4525–4550. doi:10.5194/essd-14-4525-2022. ISSN 1866-3508. https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/14/4525/2022/. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

|