Philosophy:Yama (Buddhism)

In East Asian and Buddhist mythology, Yama (Chinese: 閻魔/閻摩; pinyin: Yánmó; Wade–Giles: Yen-mo) or King Yan-lo/Yan-lo Wang (Chinese: 閻羅王; pinyin: Yánluó Wáng; Wade–Giles: Yen-lo Wang), also known as King Yan/Yan Wang (Chinese: 閻王; pinyin: Yánwáng; Wade–Giles: Yen-wang), Grandfatherly King Yan (Chinese: 閻王爺; pinyin: Yánwángyé; Wade–Giles: Yen-wang-yeh), Lord Yan (Chinese: 閻君; pinyin: Yánjūn; Wade–Giles: Yen-chün), and Yan-lo, Son of Heaven (Chinese: 閻羅天子; pinyin: Yánluó Tiānzǐ; Wade–Giles: Yen-lo T'ien-tzu), is the King of Hell and a dharmapala (wrathful god) said to judge the dead and preside over the Narakas[lower-alpha 1] and the cycle of saṃsāra.

Although based on the god Yama of the Hindu Vedas, the Buddhist Yama has spread and developed different myths and different functions from the Hindu deity. He has also spread far more widely and is known in most countries where Buddhism is practiced, including China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, Bhutan, Mongolia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos.

In Theravāda Buddhism

In the Pali canon, the Buddha states that a person who has ill-treated their parents, ascetics, holy persons, or elders is taken upon his death to Yama.[lower-alpha 2] Yama then asks the ignoble person if he ever considered his own ill conduct in light of birth, deterioration, sickness, worldly retribution and death. In response to Yama's questions, such an ignoble person repeatedly answers that he failed to consider the karmic consequences of his reprehensible actions and as a result is sent to a brutal hell "so long as that evil action has not exhausted its result."[1]

In the Pali commentarial tradition, the scholar Buddhaghosa's commentary to the Majjhima Nikaya describes Yama as a vimānapeta (विमानपेत), a "being in a mixed state", sometimes enjoying celestial comforts and at other times punished for the fruits of his karma. However, Buddhaghosa considered his rule as a king to be just.[2]

Modern Theravādin countries portray Yama sending old age, disease, punishments, and other calamities among humans as warnings to behave well. At death, they are summoned before Yama, who examines their character and dispatches them to their appropriate rebirth, whether to earth or to one of the heavens or hells. Sometimes there are thought to be two or four Yamas, each presiding over a distinct Hell.[2][lower-alpha 3]

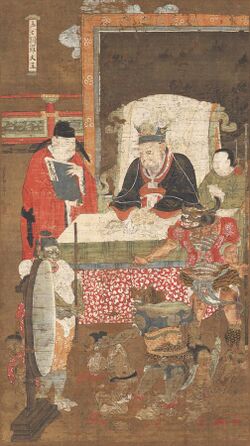

In Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Japanese mythology

In Chinese mythology, Chinese religion, and Taoism, King Yan (simplified Chinese: 阎王; traditional Chinese: 閻王; pinyin: Yánwáng) is the god of death and the ruler of Diyu, overseeing the "Ten Kings of Hell" in its capital of Youdu. He is also known as King Yanluo/Yanluo Wang (阎罗王; 閻羅王; Yánluówáng), a transcription of the Sanskrit for "King Yama" (यम राज/閻魔羅社, Yama Rāja). In both ancient and modern times, Yan is portrayed as a large man with a scowling red face, bulging eyes, and a long beard. He wears traditional robes and a judge's cap or a crown which bears the character for "king" (王). He typically appears on Chinese hell money in the position reserved for political figures on regular currency.

According to legend, he is often equated with Yama from Buddhism, but actually, Yanluo Wang has his own number of stories and long been worshiped in China. Yan is not only the ruler but also the judge of the underworld and passes judgment on all the dead. He always appears in a male form, and his minions include a judge who holds in his hands a brush and a book listing every soul and the allotted death date for every life. Ox-Head and Horse-Face, the fearsome guardians of hell, bring the newly dead, one by one, before Yan for judgement. Men or women with merit will be rewarded good future lives or even revival in their previous life. Men or women who committed misdeeds will be sentenced to suffering or miserable future lives. In some versions, Yan divides Diyu into eight, ten, or eighteen courts each ruled by a Yan King, such as King Chujiang, who rules the court reserved for thieves and murderers.

The spirits of the dead, on being judged by Yan, are supposed to either pass through a term of enjoyment in a region midway between the earth and the heaven of the gods or to undergo their measure of punishment in the nether world. Neither location is permanent and after a time, they return to Earth in new bodies.

"Yan" was sometimes considered to be a position in the celestial hierarchy, rather than an individual. There were said to be cases in which an honest mortal was rewarded the post of Yan and served as the judge and ruler of the underworld.[citation needed] Some said common people like Bao Zheng, Fan Zhongyan, Zhang Binglin became the Yan at night or after death.[3][4][5][better source needed]

Drawing from various India n texts and local culture, the Chinese tradition proposes several versions concerning the number of hells and deities who are at their head. It seems that originally there were two competing versions: 136 hells (8 big ones each divided into 16 smaller ones) or 18 hells, each of them being led by a subordinate king of Yanluo Wang.

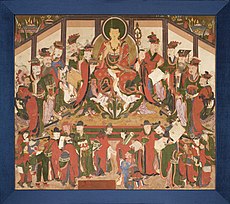

They were strongly challenged from the Tang dynasty by a new version influenced by Daoism, which adopted Yanluo Wang to make it the fifth of a set of ten kings (shidian Yánluó wáng 十殿阎罗王, Guardian king-sorter of the ten chambers) each named at the head of a hell by the Jade Emperor. The other nine kings are: Qinguangwang (秦广王), Chujiangwang (楚江王), Songdiwang (宋帝王), Wuguanwang (五官王), Bianchengwang (卞城王), Taishanwang (泰山王), Pingdengwang (平等王) Dushiwang (都市王) Zhuanlunwang (转轮王), typically Taoist names. They compete with Heidi, another Taoist god of the world of the dead. Yanluo Wang remains nevertheless the most famous, and by far the most present in the iconography.[6]

However, then it disappears completely from the list, giving way to a historical figure, a magistrate appointed during his lifetime as judge of the dead by a superior deity. This magistrate is most often Bao Zheng, a famous judge who lived during the Song dynasty. Sometimes he is accompanied by three assistants named "Old Age", "Illness" and "Death".[7]

Yama is also regarded as one of the Twenty Devas (二十諸天 Èrshí Zhūtiān) or the Twenty-Four Devas (二十四諸天 Èrshísì zhūtiān), a group of protective Dharmapalas, in Chinese Buddhism.[8]

Some of these Chinese beliefs subsequently spread to Korea, Japan and Vietnam. In Japan, he is called Enma (閻魔, prev. "Yenma"), King Enma (閻魔王, Enma-ō), and Great King Enma (閻魔大王, Enma Dai-Ō). In Korea, Yan is known as Yeom-ra (염라) and Great King Yeom-ra' (염라대왕, Yŏm-ra Daewang). In Vietnam, these Buddhist deities are known as Diêm La Vương (閻羅王) or Diêm Vương (閻王), Minh Vương (冥王) and are venerated as a council of all ten kings who oversee underworld realm of âm phủ, and according to the Vietnamese concept, the ten kings of hell are all governed by Phong Đô Đại Đế (酆都大帝).[9]

A Japanese proverb states "When borrowing, the face of a jizō; when repaying (a loan), the face of Enma" (借りる時の地蔵顔、返す時の閻魔顔 Kariru toki no jizōgao, kaesu toki no enmagao). Jizō is typically portrayed with a serene, happy expression whereas Enma is typically portrayed with a thunderous, furious expression. The kotowaza alludes to changes in people's behaviour for selfish reasons depending on their circumstances.[citation needed]

Variable identity

In the syncretic and non-dogmatic world of Chinese religious views, Yanluo Wang's interpretation can vary greatly from person to person. While some recognize him as a Buddhist deity, others regard him as a Taoist counterpart of Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha. Generally seen as a stern deity, Yanluo Wang is also a righteous and fair Supreme Judge in underworld or skillful advocate of Dharma.

In Tibetan Buddhism

In Tibetan Buddhism Yama occurs in the form of Yama Dharmaraja, also known as Kalarupa,[10][11] Shinje or Shin Je Cho Gyal (Tibetan: གཤིན་རྗེ་, Gshin.rje).[10][12] He is both regarded with horror as the prime mover of the cycle of death and rebirth and revered as a guardian of spiritual practice. In the popular mandala of the Bhavachakra, all of the realms of life are depicted between the jaws or in the arms of a monstrous Shinje. Shinje is sometimes shown with a consort, Chamundi, or a sister, Yami,[13] and sometimes pursued by Yamantaka (conqueror of death).

He is often depicted with the head of a buffalo, three round eyes, sharp horns entwined with flame, fierce and angry. In his right hand he often has a stick with a skull and in his left a lasso. On his head he has a crown of skulls. In many depictions he is standing on a recumbent bull crushing a man lying on his back. He is also portrayed with an erect penis.[14]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Meaning "Hells", "Hell Realm", or "Purgatories".

- ↑ See, for example, MN 130 (Nanamoli Bodhi) and AN 3.35 (Thera Bodhi), both of which are entitled "Devaduta Sutta" (The Divine Messengers).

- ↑ According to (Nanamoli Bodhi) the Majjhima Nikaya Atthakatha states that "there are in fact four Yamas, one at each of four gates (of hell?)." The paranthetical expression is from the text.

References

- ↑ Nanamoli & Bodhi 2001, p. 1032.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nanamoli & Bodhi 2001, p. 1341, n. 1206.

- ↑ 七閻羅王信仰[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 中国古代传说中的三大阎王:包公寇准范仲淹

- ↑ 学子 | 真有阎王阴界,虽唯心造,因果丝毫不爽!

- ↑ Chenivesse, Sandrine (1998) (in fr). Fengdu: cité de l'abondance, cité de la male mort. pp. 287–339. https://www.persee.fr/doc/asie_0766-1177_1998_num_10_1_1137.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in Chinese). http://ez-dao.com/daobook/B/qa/(67)%2520-q@a1.htm. - ↑ Hodous, Lewis; Soothill, William Edward (2004). A dictionary of Chinese Buddhist terms: with Sanskrit and English equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-203-64186-8. OCLC 275253538.

- ↑ Tuyển tập Vũ Bằng. Văn học. 2000. pp. 834. https://books.google.com/books?id=PFzB32AUWhkC&q=phong+%C4%91%C3%B4+%C4%91%E1%BA%A1i+%C4%91%E1%BA%BF.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Samiksha (2020-04-03). "Interpreting Yama Dharmaraja Thangka" (in en-EN). https://mandalas.life/2020/interpreting-yama-dharmaraja-thangka/.

- ↑ "Yama Dharmaraja (Buddhist Protector) - Outer (Himalayan Art)". https://www.himalayanart.org/items/700009.

- ↑ "Buddhist Protector: Yama Dharmaraja Main Page". https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=178.

- ↑ Barbara Lipton, Nima Dorjee Ragnubs (1996). Treasures of Tibetan Art: Collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art. Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art. p. 169. ISBN 9780195097139.

- ↑ Pratapaditya Pal (1983). Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520051409.

Sources

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu; Bodhi, Bhikkhu (2001). The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-072-X.

- Thera, Nyanaponika; Bodhi, Bhikkhu (1999). Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: An Anthology of Suttas from the Anguttara Nikaya. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7425-0405-0.

- "阎罗王是如何由来的:钟馗和阎王什么关系-历史趣闻网". lishiquwen.com. http://wap.lishiquwen.com/news/24627.html.

- "道教科仪之十王转案科_斋醮科仪_道教之音_十王转案,十王,冥府,道教科仪". www.daoisms.org. http://www.daoisms.org/article/sort026/info-16433.html.

External links

|