Company:Antony Gibbs & Sons

| Type |

|

|---|---|

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Successor |

|

| Founded | 1808 |

| Founder |

|

| Defunct | 22 June 2005 |

Number of locations |

|

Area served | Global |

Key people |

|

| Services |

|

| Subsidiaries | Gibbs, Bright & Co. |

Antony Gibbs & Sons was a British trading company, established in London in 1802, whose interests spanned trading in cloth, guano, wine and fruit, and led to it becoming involved in banking, shipping and insurance. Having been family-owned via a partnership from its foundation, by the turn of the 20th century it was focused on banking and insurance. Floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1973, it was bought by HSBC in 1981 and formed the basis of its insurance broking arm, now part of global insurance company Marsh & McLennan.

Background

Antony Gibbs (1756–1816) from Clyst St Mary, Devon, was the fourth son of Dr. George Abraham Gibbs (1718–1794), who rose to be Chief Surgeon at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. After leaving Exeter Grammar School, Antony was apprenticed to merchant Nicholas Brooke, whose firm traded with Spain exporting locally made woollen cloth. Brooke sent Antony to Madrid, where he developed Spanish language skills, and an extensive personal network that included the King of Spain, his court, government and also the civil servants who managed Spain's extensive colonies abroad.

In 1778 due to the extensive wars in mainland Europe, Antony returned to Exeter and formed Gibbs Brothers Cloth Makers with his older brother Abraham and with financial backing from their father, in a warehouse in Exwick. However, after the death of weaver Abraham in 1782, Antony married his brother's former fiancée Dolly and continued with the brothers' business plans. However, his subsequent cloth weaving business activities without the expertise of weaver Abraham went bankrupt through over trading, resulting in the subsequent bankruptcy of both Anthony and his father.[1]

Relocating to Madrid again with his wife, Antony wished to clear his name and repay his creditors. There he reformed his personal network, and again began exporting cloth from England, and also found profit in exporting Spanish wine and fruit back to the United Kingdom.[2][3] After the birth of their second son William in 1790, the family returned to Devon, living at Lower Cleave.[1]

After being sent in 1800 to Blundell's School, Tiverton, in 1802 William was withdrawn to accompany his father and brother on business trips to Spain, until in 1806 he was apprenticed to his uncle George Gibbs of Redland, Bristol. With trade to Spain decaying, in the same year with the help of his brother Sir Vicary Gibbs, Antony procured a licence for a Spanish merchant vessel to take his stock to South America; the Hermosa Mexicana arrived in Lima, Peru in 1807.[1]

Foundation

In 1808, Antony relocated his family and business to London, buying a home on Dulwich Common. With the help of Sir Vicary he was named as one of four Commissioners appointed by Order in Council dealing with the Portuguese government's British property interests. As a result, he founded merchants Antony Gibbs & Co.[1][2][3][4]

Joined in 1808 by his eldest son George Henry, he expanded the business into merchant banking. In 1813, the two were joined by William, when the company was renamed Antony Gibbs & Sons, a partnership with board members Antony, George Henry, William and at partnership level included Sir Vicary.[1][2] William was sent to Spain, but on the death of his father in 1815 returned home to run the business with his brother. The two vowed to repay their father and grandfather's debts from their bankruptcies, and had fully done so with all interest by 1840. Henry died in 1842.[1][2]

Family partnership

From its foundation until its listing on the London Stock Exchange in 1973, the company was formed and operated as a partnership in which the extended Gibbs family of grandfather Dr. George Abraham Gibbs all had a share.[1][2] Secondly, as was usual with Victorian families, they 'did business' with each other and various members of the extended family who were associated in numerous ways.[1][2]

Gibbs, Bright & Co.

In 1814, Robert Bright joined George Gibbs & Son of Bristol, the families Uncle's shipping business in which William had taken a stake. In 1816, Robert Bright replaced William as Antony Gibbs & Sons representative in Spain. After the death of George Gibbs in 1818, the firm was renamed as Gibbs, Bright & Co. of Bristol and Liverpool, with partners George Gibbs Jnr (managing), William Gibbs and Robert Bright.[5]

Until this point, the firm had been involved in the West African slave trade to and in the Caribbean, and continued to be so. However, now acting as the global shipment and shipping contractor to Antony Gibbs & Sons, this trade now began to dominate the firm's balance sheet. After the retirement of George Gibbs Jnr in 1839, Bright replaced him as managing partner, and then ceased the firm's slave trading activities on 10 September 1841.[5]

In 1881, after the death of William Gibbs and the later retirement of Robert Bright, the firm was fully acquired and absorbed into Anthony Gibbs & Sons.[5]

SS Great Britain

In 1846, the captain of Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain ran the ship hard aground in Dundrum Bay on the northeast coast of Ireland.[6] After being floated free a year later in August 1847 at a cost of £34,000, she was taken back to Liverpool and languished there for a year before being sold to Gibbs, Bright & Co. for £25,000, who had been her shipping agents when she had been based from Bristol.

Instead of just recommissioning her, the firm agreed to a complete refit, that:

- Completely renewed a 150-foot (46 m) length of the keel

- Strengthen the hull, bow and stern

- Replaced the engines with a pair of smaller, lighter and more modern oscillating engines, with 82 1⁄2-inch (210 cm) cylinders and 6-foot (180 cm) stroke, built by John Penn & Sons of Greenwich

- Replaced the chain-drive with a proven cog-wheel arrangement

- Replaced the original three large boilers with six new smaller ones, operating at 10 psi (69 kPa). This allowed the ship's cargo capacity to be almost doubled, from 1,200 to 2,200 tons.[7]

- Added a new 300-foot (91 m) cabin on the main deck

- Replaced the four-bladed propeller with a three-bladed model

In this guise she undertook one more trip to New York under the flag of Gibbs, Bright & Co., before they sold her to Antony Gibbs & Sons. Gibbs, Bright & Co. remained the ship's agents and operators, and under instruction employed Great Britain to exploit a temporary demand for passenger service to the Australian gold fields following the discovery of gold in Australia in 1851.[8] In 1852, Great Britain made her first voyage to Melbourne, carrying 630 emigrants. She excited great interest there, with 4,000 people paying a shilling each to inspect her. On her return to Liverpool, she was given a third refit:

- Passenger accommodations were increased from 360 to 730

- Sail plan altered to a traditional three-masted, square-rigged pattern

- Fitted with a removable propeller, which could be hauled up onto deck by means of chains to reduce drag when the vessel was operating under sail power alone

From 1854, Robert's son Charles Edward Bright became the firm's representative in Australia, and later partner in the firm. Great Britain continued to operate on the England–Australia route for almost thirty years, interrupted only by two relatively brief sojourns as a troopship—first during the Crimean War and later during the Indian Mutiny. Gradually, she came to earn a reputation for herself as the most reliable of the emigrant ships to Australia.

In 1882 the Great Britain was converted into a sailing ship to transport bulk coal, but after a fire on board in 1886 she was found on arrival at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands to be damaged beyond repair. She was sold to the Falkland Islands Company and used, afloat, as a storage hulk (coal bunker) until 1937, when she was towed to Sparrow Cove, 3.5 miles from Port Stanley, scuttled and abandoned.

Guano trade

From 1790 onwards, following the earlier American War of Independence and the French Revolution , the wave of Latin American Wars of Independence took place, creating a number of independent countries in Latin America from the formerly Spanish, Portuguese and French colonies. In a bid to generate cash and hence tax revenue, these new countries looked to export their natural resources back to the industrialised Europe. The Gibbs's being well connected in these Spanish-speaking circles, but not being Spanish and hence associated with the former colonial administration, had an advantage.[2][3]

The firm had opened an agents office in Lima in 1822. In 1841, the agent announced he was about to sign contracts with the Peruvian and Bolivian governments to purchase consignments of guano. William called it "an act of insanity" because of the huge loans needed to facilitate the business. Rich in nitrogen and phosphate, guano soon became accepted in England and Europe for the same purpose, with 211,000 tons imported via the ports of Bristol and London in 1856.[1] The firm's profits from this trade were such that William became the richest non-noble man in England,[2][3] remembered in the Victorian music hall ditty:[1]

| “ | William Gibbs made his dibs, Selling the turds of foreign birds | ” |

Within a few years however, cheaper products such as nitrate of soda and super phosphate fertilisers were available. Hence by 1880 the company had moved its South American base to Chile , where it manufactured nitrate of soda and its by-product iodine, both of which were in high demand for use in the burgeoning European and North American munitions trade.[1][2]

1850s onwards

In 1843 Henry Hucks Gibbs (later Lord Aldenham), nephew of William, joined the business and became more and more involved in running it. When William retired, he left Henry in charge. Finally he bequeathed the majority of his share in the partnership to Hucks on his death, which ensured continuity and also transferred ownership of the business to the Aldenham side of the family.[1][2]

Merchant bank

Henry Hucks Gibbs drove the business more towards Merchant banking, so successfully that the firm financed the construction of the Great Western Railway, and Brunel's SS Great Eastern, a ship that they also insured via the developing insurance brokerage business.[1]

From 1853 to 1901, Henry Hucks Gibbs was a Director of the Bank of England, and its Governor from 1875 to 1877. In the late 1880s, Barings Bank daring efforts in underwriting got the firm into serious trouble through overexposure to Argentine and Uruguayan debt. In 1890, Argentine president Miguel Juárez Celman was forced to resign following the Revolución del Parque, and the country was close to defaulting on its debt payments. This crisis finally exposed the vulnerability of Barings position. Lacking sufficient reserves to support the Argentine bonds until they got their house in order, the bank had to be rescued by a consortium organised by the then governor of the Bank of England, William Lidderdale, with the commercial consortia headed by Henry Hucks Gibbs and the family firm.[1] The resulting turmoil in financial markets became known as the Panic of 1890.

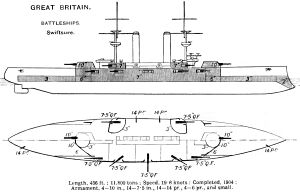

Swiftsure-class battleship

In late 1901, Chile and Argentina were on the brink of war, and Chile was concerned about its navy's ability to counter the armoured cruisers Rivadavia and Moreno, which Argentina had ordered from Italy earlier that year. Sir Edward Reed, chief designer for Armstrong Whitworth, was in Chile for health reasons at the time, and met with Chilean Navy officials to discuss the idea of purchasing or building two battleships with high speed and a powerful armament on a low displacement. Purchase of existing ships was not a practical option, so the Chileans asked Reed to design the ships for construction in the UK. Chile ordered the ships in 1901: Constitución from Armstrong Whitworth at Elswick; Libertad from Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness.[9]

Considered second-class battleships, Chile had required the ships to fit into the graving dock at Talcahuano, so they had to be longer and narrower for their displacement than ships built to British standards. Details in mast and anchor arrangements as well as the arrangement of magazines and shell-handling rooms also were different from British standards.[10]

As part of the Pacts of May, which ended the near-war tensions between Argentina and Chile, Argentina sold its two armoured cruisers that were under construction in Italy to Japan. As a result, in 1903 Chile also put its battleships up for sale. While the United Kingdom was not entirely interested in the ships, international politics took precedence: when the Russian Empire made an offer for the ships, the British grew concerned that the ships could be used against their new ally Japan. By now Antony Gibbs & Sons was run by the partnership of Members of Parliament (MP's) Alban Gibbs and his younger brother Vicary Gibbs.[11] After representation to the Admiralty and Antony Gibbs & Sons jointly by a delegation of Argentine, Chilean and Japanese diplomats, the brothers offered to finance the Admiralty's purchase of the ships by companies merchant banking arm. As a result, the Admiralty purchased both Chilean battleships on 3 December 1903 for £2,432,000.[12][13]

However, under an old law which debarred MPs from accepting contracts from the Crown, the transaction triggered two by-elections, in which Alban was re-elected unopposed,[14] but Vicary lost his seat.[15] Both ships were subsequently modified for service with the Royal Navy, with Constitución entering service in June 1904 as HMS Swiftsure, and Libertad soon afterwards as HMS Triumph.[16]

Later history

In 1973, the company was floated on the London Stock Exchange. During the initial float, Midland Bank acquired a stake, and in 1981 HSBC acquired the complete business to form the basis of HSBC Insurance Brokers.[1][17] Having dissolved the company in 2005 and fully absorbed the assets ito their group structure, HSBC later sold their commercial insurance broking arm to Marsh McLelland in 2012, many of which include the Gibbs name.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 "William Gibbs". Exeter Memories. http://www.exetermemories.co.uk/em/_people/gibbs-william.php. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 James Miller (25 May 2006). Fertile Fortune – The Story of Tyntesfield. National Trust. ISBN 1905400403.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Terry Steven (17 January 2011). "History of the House and Family at Tyntesfield". Kennet Valley National Trust. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160114075411/http://http//. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Oxford DNB: Antony Gibbs

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Gibbs, Bright & Co.". University College London. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/firm/view/-1218981458. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ↑ Ted Osborn (June 2010). "Great Britain Sinks!". Cruising (The Cruising Association): 24–26.

- ↑ Fletcher, R. A. (1910): Steamships: The Story Of Their Development To The Present Day, Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd., London, pp. 225–227

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 227.

- ↑ Burt, pp. 259, 261

- ↑ Burt, pp. 262, 264

- ↑ "Commons Sitting – New Writs". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 2 February 1904. col. 74–75. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1904/feb/02/new-writs#column_74.

- ↑ Burt, p. 262

- ↑ Scheina, pp. 49–52, 298–99, 349.

- ↑ Craig, p. 11

- ↑ Craig, p. 297

- ↑ Burt, pp. 259, 261–62

- ↑ Michelle Worvell (1 December 2008). "Philip Gregory". Professional Broking. http://www.insuranceage.co.uk/professional-broking/interview/1193147/philip-gregory-a-giant-awakes. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

|