Biology:Aegle marmelos

| Bael | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Subfamily: | Aurantioideae |

| Genus: | Aegle Corrêa[3] |

| Species: | A. marmelos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aegle marmelos | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Aegle marmelos, commonly known as bael (or bili[4] or bhel[5]), also Bengal quince,[2] golden apple,[2] Japanese bitter orange,[6] stone apple[7][8] or wood apple,[6] is a species of tree native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.[2] It is present in India , Pakistan , Bangladesh,[9] Sri Lanka, and Nepal as a naturalized species.[2][9] The tree is considered to be sacred by Hindus and Buddhists.

Description

Aegle marmelos is a deciduous shrub or small to medium-sized tree, up to 13 metres (43 feet) tall with slender drooping branches and rather open, irregular crown.[10]

Bark

The bark is pale brown or grayish, smooth or finely fissured and flaking, armed with long straight spines, 1.2–2.5 centimetres (1⁄2–1 inch) singly or in pairs, often with slimy sap oozing out from cut parts. The gum is also described as a clear, gummy sap, resembling gum arabic, which exudes from wounded branches and hangs down in long strands, becoming gradually solid. It is sweet at first taste and then irritating to the throat.[8]

Leaves

The leaf is trifoliate, alternate, each leaflet 5–14 cm (2–5 1⁄2 in) x 2–6 cm (3⁄4–2 1⁄4 in), ovate with tapering or pointed tip and rounded base, untoothed or with shallow rounded teeth. Young leaves are pale green or pinkish, finely hairy while mature leaves are dark green and completely smooth. Each leaf has 4–12 pairs of side veins which are joined at the margin.

Flowers

The flowers are 1.5 to 2 cm, pale green or yellowish, sweetly scented, bisexual, in short drooping unbranched clusters at the end of twigs and leaf axils. They usually appear with young leaves. The calyx is flat with 4(5) small teeth. The four or five petals of 6–8 millimetres (1⁄4–3⁄8 in) overlap in the bud. Many stamens have short filaments and pale brown, short style anthers. The ovary is bright green with an inconspicuous disc.

Fruits

The fruit typically has a diameter of between 5 and 10 cm (2 and 4 in).[11] It is globose or slightly pear-shaped with a thick, hard rind and does not split upon ripening. The woody shell is smooth and green, gray until it is fully ripe when it turns yellow. Inside are 8 to 15 or 20 sections filled with aromatic orange pulp, each section with 6 (8) to 10 (15) flattened-oblong seeds each about 1 cm long, bearing woolly hairs and each enclosed in a sac of adhesive, transparent mucilage that solidifies on drying. The exact number of seeds varies in different publications. The fruit takes about 11 months to ripen on the tree, reaching maturity in December.[11] It can reach the size of a large grapefruit or pomelo, and some are even larger. The shell is so hard it must be cracked with a hammer or machete. The fibrous yellow pulp is very aromatic. It has been described as tasting of marmalade and smelling of roses. Boning (2006) indicates that the flavor is "sweet, aromatic and pleasant, although tangy and slightly astringent in some varieties. It resembles a marmalade made, in part, with citrus and, in part, with tamarind."[12] Numerous hairy seeds are encapsulated in a slimy mucilage.

Chemistry

The bael tree contains furocoumarins, including xanthotoxol and the methyl ester of alloimperatorin, as well as flavonoids, rutin and marmesin; a number of essential oils; and, among its alkaloids, á-fargarine(=allocryptopine), O-isopentenylhalfordinol, O-methylhafordinol.[13] Aegeline (N-[2-hydroxy-2(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl]-3-phenyl-2-propenamide) is a constituent that can be extracted from bael leaves.[14][15]

Aeglemarmelosine, molecular formula C16H15NO2 [α]27D+7.89° (c 0.20, CHCl3), has been isolated as an orange viscous oil.[16]

Taxonomy

Bael is the only member of the monotypic genus Aegle.[9]

Habit and habitat

Aegle marmelos is native across the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, and is cultivated throughout Sri Lanka, Tamilnadu, Thailand, and Malesia.[2] It occurs in dry, open forests on hills and plains at altitudes from 0–1,200 m (0–3,937 ft) with mean annual rainfall of 570–2,000 mm (22–79 in).[8][9] It has a reputation in India for being able to grow in places that other trees cannot. It copes with a wide range of soil conditions (pH range 5–10), is tolerant of waterlogging and has an unusually wide temperature tolerance from −7–48 °C (19–118 °F).[9] It requires a pronounced dry season to give fruit.

Ecology

The tree is a larval food plant for the following two Indian Swallowtail butterflies: the lime butterfly (Papilio demoleus) and the common Mormon (Papilio polytes).

Toxicity

Aegeline is a known constituent of the bael leaf and consumed as a dietary supplement with the intent to produce weight loss.[14][15] In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Defense Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, and Hawaii state and local health officials identified an outbreak of 97 persons with acute non-viral hepatitis that first emerged in Hawaii. Seventy-two of these persons had reported using the dietary supplement containing aegeline, called OxyElite Pro which was manufactured by the Dallas company, USPlabs.[14][17] FDA had previously taken action against an earlier formulation of OxyElite Pro because it contained dimethylamylamine, a stimulant that FDA had determined to be an adulterant when included in dietary supplements and could cause high blood pressure and lead to heart attacks, seizures, psychiatric disorders, and death.[17] USPlabs subsequently reformulated this product without informing FDA or submitting the required safety data for a new dietary ingredient.[17]

Doctors at the Liver Center at The Queen's Medical Center investigating the first cases in Hawaii reported that between May and September 2013, eight previously healthy individuals presented themselves at their center suffering from a drug-induced liver injury.[14][18] All of these patients had been using the reformulated OxyElite Pro, which they had purchased from different sources, and which had different lot numbers and expiration dates, at doses within the manufacturer's recommendation.[14][18] Three of these patients developed fulminant liver failure, two underwent urgent liver transplantation, and one died.[14][18] The number of such cases would ultimately rise to 44 in Hawaii.[14][18] In January 2014, leaders from the Queen's Liver Center informed state lawmakers that they were almost certain that aegeline was the agent responsible for these cases,[19] but the mechanism of how aegeline may damage the liver has not been isolated.[14]

Uses

Culinary

Rich in vitamin C,[11] the fruits can be eaten either fresh from trees or after being dried[20] and produced into candy, toffee, pulp powder or nectar.[9] If fresh, the juice is strained and sweetened to make a drink similar to lemonade.[11] It can be made into sharbat, also called as Bela pana, a beverage. Bela Pana made in Odisha has fresh cheese, milk, water, fruit pulp, sugar, crushed black pepper, and ice. Bæl pana, a drink made of the pulp with water, sugar, and citron juice, is mixed, left to stand a few hours, strained, and put on ice. One large bael fruit may yield five or six liters of sharbat. If the fruit is to be dried, it is usually sliced and sun-dried. The hard leathery slices are then immersed in water. The leaves and small shoots are eaten as salad greens. Bael fruits are of dietary use and the fruit pulp is used to prepare delicacies like murabba, puddings and juices.

Traditional medicine

The leaves, bark, roots, fruits, and seeds are used in traditional medicine to treat various illnesses,[9] although there is no clinical evidence that these methods are safe or effective.[citation needed]

In culture

Bael is considered one of the sacred trees of Hindus[21] (known in Sanskrit as बिल्व bilva[22]) thus are used in ritual rites.[23][24] Earliest evidence of religious importance of bael appears in the Sri Sukta of the Rigveda, which reveres this plant as the residence of goddess Lakshmi, the deity of wealth and prosperity.[25] Bael trees are also considered an incarnation of goddess Sati.[26] Bael trees can be usually seen near the Hindu temples and their home gardens.[27] It is believed that Shiva is fond of bael trees to a point of earning the epithet बिल्वदण्ड Bilvadaṇḍa or "bel-staffed".[22] Its leaves and fruit still play a main role in his worship, because the leaf's triple shape symbolises his trident.[28]

In the traditional practice of the Hindu and Buddhist religions by people of the Newar culture of Nepal, the bael tree is part of a fertility ritual for girls known as the Bel Bibaaha. Girls are "married" to the bael fruit; as long as the fruit is kept safe and never cracks, the girl can never become widowed, even if her human husband dies. This is a ritual that guarantees the high status of widows in the Newar community compared to other women in Nepal.[29]

References

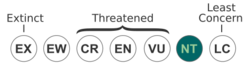

- ↑ Plummer, J. (2020). Aegle marmelos. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T156233789A156238207. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T156233789A156238207.en. Downloaded on 07 March 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Taxon: Aegle marmelos (L.) Corrêa". GRIN Global, National Plant Germplasm System, US Department of Agriculture. 19 September 2017. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?1560.

- ↑ "genus Aegle". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) online database. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomygenus.aspx?id=228.

- ↑ "FOI search results". flowersofindia.net. http://www.flowersofindia.net/risearch/search.php?query=bili&stpos=0&stype=AND.

- ↑ Wilder, G.P. (1907), Fruits of the Hawaiian Islands, Hawaiian Gazette, ISBN 9781465583093, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZRN1DZJPhuMC

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "M.M.P.N.D. - Sorting Aegle names". unimelb.edu.au. http://www.plantnames.unimelb.edu.au/Sorting/Aegle.html.

- ↑ "Bael: Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa". Philippine Medicinal Plants. http://www.stuartxchange.org/Bael.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Orwa, C (2009). "Aegle marmelos". Agroforestree Database:a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0. http://www.worldagroforestry.org/treedb/AFTPDFS/Aegle_marmelos.PDF.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Misra KK (1999). "Bael". NewCROP, the New Crop Resource Online Program, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Purdue University, W. Lafayette, IN. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/CropFactSheets/bael.html.

- ↑ Gardner, Simon (2007). Field guide to forest trees of Northern Thailand. Bangkok: Kobfai Publishing Project. pp. 102. ISBN 978-974-8367-29-3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 (in en-US) The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. United States Department of the Army. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. 2009. pp. 23. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/277203364.

- ↑ Boning, Charles (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc.. p. 35.

- ↑ Rasadah Mat Ali; Zainon Abu Samah; Nik Musaadah Mustapha; Norhara Hussein (2010). Aegle marmelos (L.): In ASEAN Herbal and Medicinal Plants (page 107). Jakarta, Indonesia: Association of Southeast Asian Nations. p. 43. ISBN 978-979-3496-92-4. http://www.asean.org/uploads/archive/publications/aseanherbal2010.pdf.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 "Hepatotoxicity associated with weight loss or sports dietary supplements, including OxyELITE Pro™ - United States, 2013". Drug Test Anal 9 (1): 68–74. 2017. doi:10.1002/dta.2036. PMID 27367536.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Avula, B; Chittiboyina, A. G; Wang, Y. H et al. (2016). "Simultaneous Determination of Aegeline and Six Coumarins from Different Parts of the Plant Aegle marmelos Using UHPLC-PDA-MS and Chiral Separation of Aegeline Enantiomers Using HPLC-ToF-MS". Planta Medica 82 (6): 580–8. doi:10.1055/s-0042-103160. PMID 27054911.

- ↑ Laphookhieo, Surat (2011). "Chemical constituents from Aegle marmelos". J. Braz. Chem. Soc. [online] 22: 176–178. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-50532011000100024&lng=en&nrm=iso.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "FDA Investigation Summary: Acute Hepatitis Illnesses Linked to Certain OxyElite Pro Products". US Food and Drug Administration. 30 July 2014. https://www.fda.gov/Food/RecallsOutbreaksEmergencies/Outbreaks/ucm370849.htm.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Outbreak of severe hepatitis linked to weight-loss supplement OxyELITE Pro". Am J Gastroenterol 109 (8): 1296–8. August 2014. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.159. PMID 25091255.

- ↑ Daysong, Rick (January 28, 2014). "Months after recall, new OxyElite Pro illnesses reported". Hawaii News Now. http://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/24561216/exclusive.

- ↑ Hazra, Sudipta Kumar (2020). "Characterization of phytochemicals, minerals and in vitro medicinal activities of bael (Aegle marmelos L.) pulp and differently dried edible leathers". Heliyon 6 (10): e05382. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05382. PMID 33163665. Bibcode: 2020Heliy...605382H.

- ↑ Panda, H (2002). Medicinal Plants Cultivation & Their Uses. Asia Pacific Business Press Inc.. p. 159. ISBN 9788178330969. https://books.google.com/books?id=nYyuAwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Monier-Williams, Monier (1981). "बिल bil". बिल bil. Delhi, Varanasi, Patna: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 684. https://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/csl-apidev/servepdf.php?dict=MW72&page=0684-c.

- ↑ Peg, Streep (2003). Spiritual Gardening: Creating Sacred Space Outdoors. New World Library. ISBN 9781930722248. https://books.google.com/books?id=olAvkAfA3zIC.

- ↑ Bakhru, HK (1995). Foods That Heal. Orient Paperbacks. pp. 28–30. ISBN 9788122200331. https://books.google.com/books?id=jyqzV-tcDRQC.

- ↑ The Astrological Magazine, Volume 92. Raman Publications. 2003. p. 48. https://books.google.com/books?id=s7Z-AAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Shambhala Publications. 2003-10-14. ISBN 9780834824232. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sp1BCwAAQBAJ&q=bel+tree+parvati&pg=PT70.

- ↑ S.M. Jain, K. Ishii (2012). Micropropagation of Woody Trees and Fruits Volume 75 of Forestry Sciences. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789401001250.

- ↑ Lim, T. K. (2012). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 4, F0000000000ruits Volume 4 of Edible Medicinal and Non-medicinal Plants: Fruits. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 613. ISBN 9789400740532. https://books.google.com/books?id=c4KuB3iGmbwC.

- ↑ Gutschow, Niels; Michaels, Axel; Bau, Christian (2008). "The Girl's Hindu Marriage to the Bel Fruit: Ihi and The Girl's Buddhist Marriage to the Bel Fruit: Ihi". Growing Up—Hindu and Buddhist Initiation Ritual among Newar Children in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Wiesbaden, GER: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 93–173. ISBN 978-3447057523. https://books.google.com/books?id=DK-eoCXM_WsC.

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|