Biology:Left-brain interpreter

The left-brain interpreter is a neuropsychological concept developed by the psychologist Michael S. Gazzaniga and the neuroscientist Joseph E. LeDoux.[1][2] It refers to the construction of explanations by the left brain hemisphere in order to make sense of the world by reconciling new information with what was known before.[3] The left-brain interpreter attempts to rationalize, reason and generalize new information it receives in order to relate the past to the present.[4]

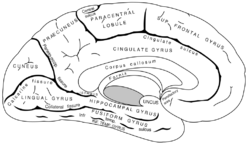

Left-brain interpretation is a case of the lateralization of brain function that applies to "explanation generation" rather than other lateralized activities.[5] Although the concept of the left-brain interpreter was initially based on experiments on patients with split-brains, it has since been shown to apply to the everyday behavior of people at large.[5]

Discovery

The concept was first introduced by Michael Gazzaniga while he performed research on split-brain patients during the early 1970s with Roger Sperry at the California Institute of Technology.[5][6][7] Sperry eventually received the 1981 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his contributions to split-brain research.[8]

In performing the initial experiments, Gazzaniga and his colleagues observed what happened when the left and right hemispheres in the split brains of patients were unable to communicate with each other. In these experiments when patients were shown an image within the right visual field (which maps to the left brain hemisphere), an explanation of what was seen could be provided. However, when the image was only presented to the left visual field (which maps to the right brain hemisphere) the patients stated that they didn’t see anything.[7][9][10]

However, when asked to point to objects similar to the image, the patients succeeded. Gazzaniga interpreted this by postulating that although the right brain could see the image it could not generate a verbal response to describe it.[10][9][7]

Experiments

Since the initial discovery, a number of more detailed experiments have been performed[11] to further clarify how the left brain "interprets" new information to assimilate and justify it. These experiments have included the projection of specific images, ranging from facial expressions to carefully constructed word combinations, and functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) tests.[4][10]

Many of the studies and experiments build on the initial approach of Gazzaniga in which the right hemisphere is instructed to do things that the left hemisphere is unaware of, e.g. by providing the instructions within the visual field that is only accessible to the right brain. The left-brain interpreter will nonetheless construct a contrived explanation for the action, unaware of the instruction the right brain had received.[6]

The typical fMRI experiments have a "block mode", in which specific behavioral tasks are arranged into blocks and are performed over a period of time. The fMRI responses from the blocks are then compared.[12] In fMRI studies by Koutstaal the level of sensitivity of the right visual cortex with respect to the single exposure of an object (e.g. a table) on two occasions was measured against the display of two distinct tables at once. This contrasted with the left hemisphere's lower level of sensitivity to variations.[4]

Although the concept of the left-brain interpreter was initially based on experiments on patients with split brains, it has since been shown to apply to the everyday behavior of people at large.[5]

A hierarchical organization of the lateral prefrontal cortex has been developed in which different regions are categorized according to different "levels" of explanation. The left lateral orbitofrontal cortex and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex generate causal inferences and explanations of events, which are then evaluated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The subjective evaluation of different internally generated explanations is then performed by the anterolateral prefrontal cortex.

Reconciling the past with the present

The drive to seek explanations and provide interpretations is a general human trait, and the left-brain interpreter can be seen as the glue that attempts to hold the story together, in order to provide a sense of coherence to the mind.[5] In reconciling the past and the present, the left-brain interpreter may confer a sense of comfort to a person, by providing a feeling of consistency and continuity in the world. This may in turn produce feelings of security that the person knows how "things will turn out" in the future.[4]

However, the facile explanations provided by the left-brain interpreter may also enhance the opinion of a person about themselves and produce strong biases which prevent the person from seeing themselves in the light of reality and repeating patterns of behavior which led to past failures.[4] The explanations generated by the left-brain interpreter may be balanced by right brain systems which follow the constraints of reality to a closer degree.[4][11] The suppression of the right hemisphere by electroconvulsive therapy leaves patients inclined to accept conclusions that are absurd but based on strictly-true logic. After electroconsulsive therapy to the left hemisphere the same absurd conclusions are indignantly rejected.[13]

The checks and balances provided by the right brain hemisphere may thus avoid scenarios that eventually lead to delusion via the continued construction of biased explanations.[4] In 2002 Gazzaniga stated that the three decades of research in the field had taught him that the left hemisphere is far more inventive in interpreting facts than the right hemisphere's more truthful, literal approach to information management.[10]

Studies on the neurological basis of different defense mechanisms have revealed that the use of immature defense mechanisms, such as denial, projection, and fantasy, is tied to glucose metabolization in the left prefrontal cortex, while more mature defense mechanisms, such as intellectualization, reaction formation, compensation, and isolation, are associated with glucose metabolization in the right hemisphere.[14] It has also been found that grey matter volume of the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex correlates with scores on measures of Machiavellian intelligence, while volume of the right medial orbitofrontal cortex correlates with scores on measures of social comprehension and declarative episodic memory.[15] These studies illustrate the role of the left prefrontal cortex in exerting control over one's environment in contrast to the role of the right prefrontal cortex in inhibition and self-evaluation.

Further development and similar models

Michael Gazzaniga, while working on the model of left-brain interpreter, came to the conclusion that simple right-brain/left-brain model of the mind is a gross oversimplification and the brain is organized into hundreds maybe even thousands of modular-processing systems.[16][17]

Similar models (which also claim that mind is formed from many little agents, i.e. the brain is made up of a constellation of independent or semi-independent agents) were also described by:

- Thomas R. Blakeslee described the brain model similar to Michael Gazzaniga’s. Thomas R. Blakeslee renamed Michael Gazzaniga’s interpreter module into the self module.[18]

- Neurocluster Brain Model describes the brain as a massively parallel computing machine in which huge number of neuroclusters process information independently from each other. The neurocluster which most of the time has the access to actuators (i.e. neurocluster which most of the time acts upon an environment using actuators) is called the main personality. The term main personality is equivalent to Michael Gazzaniga’s term interpreter module.[19]

- Michio Kaku described the brain model similar to Michael Gazzaniga’s using the analogy of large corporation in which Michael Gazzaniga’s interpreter module is equivalent to CEO of large corporation.[20]

- Marvin Minsky’s “Society of Mind” model claims that mind is built up from the interactions of simple parts called agents, which are themselves mindless.[21]

- Robert E. Ornstein claimed that the mind is a squadron of simpletons.[22]

- Ernest Hilgard described neodissociationist theory which claims that a “hidden observer” is created in the mind while hypnosis is taking place and this “hidden observer” has his own separate consciousness.[23][24]

- George Ivanovich Gurdjieff in year 1915 taught his students that man has no single, big I; man is divided into a multiplicity of small I’s. George Ivanovich Gurdjieff described the model similar to Michael Gazzaniga’s using the analogy in which the man is compared to a house which has a multitude of servants and Michael Gazzaniga’s interpreter module is equivalent to master of the servants.[25]

See also

- Dual consciousness

- Divided consciousness

- Lateralization of brain function

- Society of Mind

- Parallel computing

- Bicameralism

- Brain asymmetry

- Exformation

References

- ↑ Gazzaniga, Michael; Ivry, Richard; Mangun, George (2014). Cognitive Neuroscience. The Biology of the Mind. Fourth Edition. pp. 153.

- ↑ Gazzaniga, Michael (1985). The Social Brain. Discovering the Networks of the Mind. pp. 5.

- ↑ Neurosociology: The Nexus Between Neuroscience and Social Psychology by David D. Franks 2010 ISBN:1-4419-5530-5 page 34

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers by Daniel L. Schacter 2002 ISBN:0-618-21919-6 page 159 [1]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 The cognitive neuroscience of mind: a tribute to Michael S. Gazzaniga edited by Patricia A. Reuter-Lorenz, Kathleen Baynes, George R. Mangun, and Elizabeth A. Phelps; The MIT Press; 2010; ISBN:0-262-01401-7; pages 34-35

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions by Jan E. Stets, Jonathan H. Turner 2007 ISBN:0-387-73991-2 page 44

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Handbook of Neuropsychology: Introduction (Section 1) and Attention by François Boller, Jordan Grafman 2000 ISBN:0-444-50367-6 pages 113-114

- ↑ Trevarthen, C. (1994). "Roger W. Sperry (1913–1994)". Trends in Neurosciences 17 (10): 402–404.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Understanding psychology by Charles G. Morris and Albert A. Maisto 2009 ISBN:0-205-76906-3 pages 56-58

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Michael Gazzaniga, The split brain revisited. Scientific American 297 (1998), pp. 51–55. 37 [2]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 The cognitive neurosciences by Michael S. Gazzaniga 2004 ISBN:0-262-07254-8 pages 1192-1193

- ↑ The cognitive neuroscience of mind: a tribute to Michael S. Gazzaniga edited by Patricia A. Reuter-Lorenz, Kathleen Baynes, George R. Mangun, and Elizabeth A. Phelps; The MIT Press; 2010; ISBN:0-262-01401-7; pages 213-214

- ↑ Deglin, V. L., & Kinsbourne, M. (1996). Divergent thinking styles of the hemispheres: How syllogisms are solved during transitory hemisphere suppression. Brain and cognition, 31(3), 285-307.

- ↑ Northoff, G. (2010). Region-based approach versus mechanism-based approach to the brain. Neuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Psychoanalysis and the Neurosciences, 12(2), 167-170.

- ↑ Nestor, P. G., Nakamura, M., Niznikiewicz, M., Thompson, E., Levitt, J. J., Choate, V., ... & McCarley, R. W. (2013). In search of the functional neuroanatomy of sociality: MRI subdivisions of orbital frontal cortex and social cognition. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 8(4), 460-467.

- ↑ Gazzaniga, Michael; LeDoux, Joseph (1978). The Integrated Mind. pp. 132-161.

- ↑ Gazzaniga, Michael (1985). The Social Brain. Discovering the Networks of the Mind. pp. 77-79.

- ↑ Blakeslee, Thomas (1996). Beyond the Conscious Mind. Unlocking the Secrets of the Self. pp. 6-7.

- ↑ "Official Neurocluster Brain Model site". http://neuroclusterbrain.com.

- ↑ Kaku, Michio (2014). The Future of the Mind.

- ↑ Minsky, Marvin (1986). The Society of Mind. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 17-18. ISBN 0-671-60740-5.

- ↑ Ornstein, Robert (1992). Evolution of Consciousness: The Origins of the Way We Think. pp. 2.

- ↑ Hilgard, Ernest (1977). Divided consciousness: multiple controls in human thought and action.. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-39602-4.

- ↑ Hilgard, Ernest (1986). Divided consciousness: multiple controls in human thought and action (expanded edition).. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-80572-6.

- ↑ Ouspenskii, Pyotr (1992). "Chapter 3". In Search of the Miraculous. Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. pp. 72-83.