Engineering:Parallel-plate flow chamber

A parallel-plate fluid flow chamber is a benchtop (in vitro) model that simulates fluid shear stresses on various cell types exposed to dynamic fluid flow in their natural, physiological environment. The metabolic response of cells in vitro is associated with the wall shear stress.

A typical parallel-plate flow chamber consists of a polycarbonate distributor, a silicon gasket, and a glass coverslip. The distributor, forming one side of the parallel-plate flow chamber, includes inlet port, outlet port, and a vacuum slot. The thickness of the gasket determines the height of the flow path. The glass coverslip forms another side of the parallel-plate flow chamber and can be coated with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, vascular cells, or biomaterials of interest. A vacuum forms a seal to hold these three parts and ensures a uniform channel height.[1]

Typically, the fluid enters one side of the chamber and leaves from an opposite side. The upper plate is usually transparent while the bottom is a prepared surface on which the cells have been cultured for a predetermined period. Cell behavior is viewed with either transmitted or reflective light microscope.

Equation

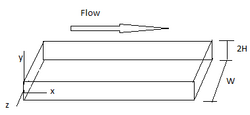

Within the chamber, fluid flow creates shear stress ([math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]) at the chamber wall, and a typical equation describing this relationship as a function of flow rate, Q, and chamber height, h, can be derived from Navier-Stokes equations and continuity equation:

[math]\displaystyle{ \rho(\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial t} + V_x\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial x} + V_y\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial y} + V_z\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial z}) = \frac{\partial P}{\partial x} + \mu (\frac{\partial ^2V_x}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial ^2V_x}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial ^2V_x}{\partial z^2}) + \rho g_x }[/math]

With the assumptions such as Newtonian Fluid, Incompressible, Laminar Flow and no slip boundary conditions, Navier-Stokes equations simplifies to:

[math]\displaystyle{ -\frac{\partial P}{\partial x} = \mu (\frac{\partial ^2V_x}{\partial y^2}) }[/math]

Solving the first differential equation will provide:

[math]\displaystyle{ -\frac{\partial P}{\partial x} y = \mu (\frac{\partial V_x}{\partial y}) + C }[/math]

Solving the second differential equation for no slip boundary condition the velocity profile is given by:

[math]\displaystyle{ V_x = \frac{1}{2\mu} \frac{\partial P}{\partial x}(H^2 - y^2) }[/math]

This can then be used in continuity equation that states:

[math]\displaystyle{ Q = \int\int_A V_x dA = W \int_{-H} ^H \frac{1}{2\mu} \frac{\partial P}{\partial x}(H^2 - y^2) dy }[/math]

Solving this integral will output:

[math]\displaystyle{ Q = \frac{2WH^3}{3\mu} \frac{\partial P}{\partial x} }[/math]

When solving the equation for the change in pressure and plugging it into the first differential equation the shear stress can be calculated for the parallel plate flow chamber.

[math]\displaystyle{ \tau = -\mu \frac{\partial V_x}{\partial y} = \frac{\partial P}{\partial x} H = \frac{3Q\mu}{2WH^2} }[/math]

In which μ is the dynamic viscosity, and w the width of the flow chamber. In these methods, the shear stresses exerted on the cells are assumed approximately equal to the chamber wall shear stresses since cell height is approximately two orders of magnitude less than the chamber.

Advantages

The parallel-plate flow chamber, in its original design, is capable of producing well-defined wall shear-stress in the physiological range of 0.01-30 dyn/cm2. Shear stress is generated by flowing fluid (e.g., anticoagulated whole blood or isolated cell suspensions) through the chamber over the immobilized substrate under controlled kinematic conditions using a syringe pump. The advantages of the parallel-plate flow chamber are:

1. It makes possible study of the effects of constant shear-stress on cells over a defined time-period.

2. The device is simple in design, assembly, and operation.

3. The cells can be grown under flow conditions, and can be observed under a microscope, or visualized in real time, utilizing video microscopy.,[2][3]

PPFC Design

The initial design of the parallel flow chamber is based upon that described by Hochmuth and colleagues to study red blood cells. The parallel plate flow chamber was used in early studies on neutrophils by Wikinson et al. and Forrestor et al. to study their adhesive characteristic on absorbed plasma proteins. Lawrence et al. described one of the first parallel flow chamber assays to study neutrophil adhesion to endothelium. Since these earlier studies, numerous researchers have utilized the parallel plate flow chamber and modified versions of it to examine the dynamics of neutrophil adhesion to various substrates, including endothelial cells, platelets, leukocytes, transfected cell lines, and purified molecules.[4]

Application

The parallel-plate flow chamber is a widely used piece of equipment for studying cellular mechanics on the benchtop. Many researchers used parallel-plate flow chambers to investigate the dynamic adhesion between leukocytes (white blood cells) and endothelial cells (blood vessel lining cells) under definite shear stress.[5] In particular, some studies have been carried out to study leukocyte receptor-ligand interactions.[6] Interactions between cell receptors (selectins and/or integrins) and their ligands mediate rolling and are believed to play an important role in leukocyte adhesion.[7] Moreover, many researchers used parallel-plate flow chambers to provide shear stress and to mimic the environment of cancer cell growth outside of the body.[8] It is a versatile tool in understanding the mechanisms of proliferation, adhesion, and metastasis of cancer cells. Parallel plate flow chambers are widely used also for drug testing in the cellular chemotaxis assay [9] and for novel targeted drug delivery systems based on leukocyte-endothelium adhesion processes.

References

- ↑ Loscalzo J., Schafer A.I. "Thrombosis and hemorrhage". Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003

- ↑ Morgan J.R., Yarmush M. L. "Tissue engineering methods and protocols". Humana Press, 1999 - Science -

- ↑ Mousa A. "Anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and thrombolytics". Humana Press, 2004 - Medical -

- ↑ Quinn M. T., Deleo F., Bokoch G. M. "Neutrophil methods and protocols". Methods in Molecular Biology. Volume 412.

- ↑ LING Xu, YE Jian-Feng, ZHENG Xiao-Xiang. "Dynamic Investigation of Leukocyte-Endothelial Cell Adhesion Interaction under Fluid Shear Stress in Vitro". Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 2003, 35(6): 567-572

- ↑ Taite, Lakeshia J.; Rowland, Maude L.; Ruffino, Katie A.; Smith, Bryan R. E.; Lawrence, Michael B.; West, Jennifer L. "Bioactive Hydrogel Substrates: Probing Leukocyte Receptor–Ligand Interactions in Parallel Plate Flow Chamber Studies". Annals of Biomedical Engineering. Vol. 34 Issue 11. 2006-11-02

- ↑ Georg K. Wiese, Steven R. Barthel, Charles J. Dimitroff. "Parallel-plate flow chamber analysis of physiologic E-selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling on microvascular endothelial cells". J Vis Exp. 2009 February 11.

- ↑ ZHAO Lian,LIAO Fu-Long, HAN Dong, ZHOU Hong. "Application of parallel-plate flow chamber in cancer research". Bulletin of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences. 2009-05

- ↑ Mario Mellado, Carlos Martínez‐A, José Miguel Rodríguez‐Frade. "Drug Testing in Cellular Chemotaxis Assays". Current Protocols in Pharmacology. Unit Number: UNIT 12.11. June, 2008

|