Engineering:Maritime Express

| Overview | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Discontinued | ||||

| Locale | Canada | ||||

| First service | 1 March, 1898 | ||||

| Last service | 26 April, 1964 (66 years) | ||||

| Former operator(s) | ICR (1904–1918), CNR (1919–1964) | ||||

| Route | |||||

| Start | Montreal | ||||

| End | Halifax | ||||

| Distance travelled | 1,346 km (836 mi) | ||||

| Average journey time | 26 hours (1957) | ||||

| Service frequency | Daily | ||||

| Train number(s) | 33, 34 (1898-1915), 3, 4 (1915-1920), 1, 2 (1920-1955), 3, 4 (1955-1964) | ||||

| Technical | |||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||||

| |||||

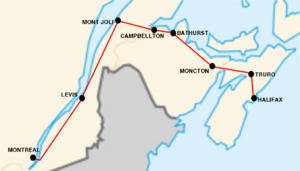

The Maritime Express was a Canada passenger train. When it was launched on the first of March, 1898, it was the flagship of the Intercolonial Railway (ICR) between Halifax, Nova Scotia and Montreal , Quebec. The train was operated by the Canadian National Railway (CNR) from 1919 until 1964, when it was reduced to a regional service and its name retired.

Construction of the Intercolonial Railway

The call for a railway to link Canada’s Maritime Provinces with the colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada (after 1840, the Province of Canada), gained momentum by the mid-1830s. In 1835, editor Joseph Howe, a future Nova Scotia premier, wrote in the Novascotian that railway construction would greatly enhance trade within the province.[1]

In April, 1846, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Sir Colin Campbell, wrote to William Gladstone, Britain’s Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs, calling for a survey of a route for a rail connection linking Halifax with Montreal. In June of that year, Captain John Pipon and Lieutenant E. Wallcott Henderson of the Royal Corps of Engineers were ordered to conduct a survey to identify the optimal route. Pipon would die in the attempt, drowned in New Brunswick’s Restigouche River in November, 1846, to be replaced by Major William Robinson.[2]

It was Robinson’s 1849 report to the legislatures of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia that would largely define the route of the interprovincial railway. He identified four advantages of a rail line that would traverse northern New Brunswick, close to the shores of the Bay of Chaleur: opening the region to settlement, reduced elevations, lower cost and the military advantage of distance from the United States border.[3]

Construction of what was to become to become the Intercolonial’s main line began in the mid-1850s, with the first trains operating on the Nova Scotia Railway between Halifax and Truro in 1858.[4] In 1864, the British and colonial governments appointed the engineer Sandford Fleming to survey possible routes[5]; by 1867 he declared his support for the northern route advocated by Robinson.[6] Construction to complete the link between the Maritimes and Quebec would wait until after Confederation in 1867. (Indeed, construction of the railway was to be a condition of the union, enshrined in the Constitution Act, 1867.)[7]

Passenger service on the Intercolonial Railway

There was no formal “last spike” commemoration when the last section of the ICR’s line between Quebec and Halifax was completed on 1 July, 1876.[8] Work had been completed in sections, with passenger and freight service offered as important communities were linked. Construction crews completed the difficult task of traversing Nova Scotia’s Cobequid Mountains in 1872[9] and the first passenger train from Halifax reached Saint John, New Brunswick on 11 November that year. (Although, not without incident, the train having been delayed three hours by a derailed ballast train.)[10] Two years later, the first trains ran between Mont-Joli, Quebec and Campbellton, New Brunswick.[4]

The first through passenger trains to link Montreal and Halifax departed on 3 July 1876, using Intercolonial tracks between Halifax and Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec, and tracks of the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) to Montreal. The trains took almost a day and a half to reach their destinations. The westbound train, called the Quebec Express, was scheduled to leave Halifax at 7:10 p.m., arriving in Montreal two days later at 6:30 a.m.; the eastbound Saint John & Halifax Express left Montreal at 10:00 p.m., arriving in Halifax at 8:25 a.m. The trains carried Pullman Company first class cars, the first sleeping cars to operate in eastern Canada.[11]

(Pullman’s presence in Atlantic Canada was short-lived. Demand for sleeping car space fell short of projections, averaging six beds per trip over the first two years. ICR ended its Pullman contract, taking over sleeping car operations, in 1885.)[12]

The schedules’ 36-hour running time required coach passengers to change trains at Point Levi, Quebec; sleeping cars were added to connecting regional trains. The trains originated and terminated at GTR’s Bonaventure Station in Montreal and North Street Station in Halifax.[13]

Inauguration of the Maritime Express

By the dawn of the 1890s, the ICR recognized the need for improved service on its Halifax-Montreal route. Beginning in 1889, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had become a direct competitor, operating its Eastern Express and Western Express trains out of Montreal’s Windsor Station via Sherbrooke, Quebec and Saint John to Halifax. Most vexing for ICR managers, the federal government had granted running rights to the CPR over ICR rails from Saint John to Halifax. By virtue of its shorter route, the CPR was able to complete the trip in three hours less than the Intercolonial trains. ICR responded by petitioning the government to extend its own tracks to Montreal through the purchase of a regional Quebec line, eliminating the need to change trains in Point-Levi. The railway also secured permission to purchase more powerful locomotives and new modern cars.[14]

On 1 March, 1898, the Intercolonial launched a faster schedule, rebranding its flagship trains as the Maritime Express. The eastbound train left Montreal at 7:30 p.m., arriving in Halifax the next day at 9:40 p.m.; westbound, the train departed Halifax at 1:30 p.m. and pulled into Bonaventure station the following day at 5:35 p.m. The trains featured first-class dining cars and sleepers built by the Wagner Palace Car Company. The sleepers featured 10 open sections and two drawing rooms, “finished in polished mahogany beautifully inlaid with lighter woods [with] ceilings of green and gold, in the Empire style, and the upholstering…of a rich green plush.”[15]

In 1900, the ICR revised the schedule of the eastbound Maritime Express to depart Montreal at 11:30 a.m., arriving in Halifax a day later at 3:30 p.m. This allowed for an early evening arrival at Point-Levi, providing a more convenient ferry connection for passengers crossing the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City. On the whole, the train proved to be popular with travellers, with a 45% increase in sleeping car revenues and a 260% jump in dining car revenues in its first year of operation. [16]

Expansion

Between 1900 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, ICR invested heavily in improvements to its rolling stock, motive power and infrastructure. It ordered new passenger cars, installed upgraded tracks and bridges to carry heavier trains, and constructed impressive new stations in communities along the line. In 1912 the railway undertook a massive project to construct a new terminus in the south end of Halifax, connecting it to the main line by blasting through miles of solid bedrock. The project would prove to be prescient when North Street Station and much of the railway’s waterfront infrastructure was wrecked by the Halifax Explosion in 1917. The Maritime Express moved to a new “temporary” south end station on 22 December, 1918 and to the new Halifax Station in 1928.[17]

The Maritime Express continued to build patronage through its first 12 years. Heavy traffic often required the addition of a second following section; in 1906 Christmas travel volumes forced the addition of a third section on part of the route. In 1904, the railway began to replace its older, lighter engines, mostly 4-6-0 “Ten-wheeler” types, with faster and more powerful 4-6-2 “Pacifics” built by Kingston Locomotive Works and Montreal Locomotive Works (MLW).[18] Travellers were enchanted by the bucolic Maritime scenery as the train skirted the Bay of Chaleur, crossed the Tantramar Marshes between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and crested the Cobequid Mountains. Journalist (and future Nova Scotia premier) William Stevens Fielding wrote in 1872 that the view of Nova Scotia’s Wentworth Valley from the train was “a scene of grandeur and beauty unequalled by any other. (…) It seemed as though the mountain were a monarch clothed in the loveliest raiment, sitting there to protect the smiling and fruitful valley. No wonder the ladies ceased their gossip, the card players threw aside their cards, and singers forgot their songs. All gazed with admiration on the beautiful scene spread out before them."[19]

The success of the Maritime Express led in 1904 to the introduction of a second Montreal-Halifax train on the route. ICR inaugurated the Ocean Limited on 3 July, 1904, calling it “the finest passenger service…it has ever had.” [20] Begun as a seasonal summer service, it was expanded to a year-round operation in 1912, becoming a full running mate to the Maritime Express. Like other trains bestowed with the name “Limited”, the Ocean Limited made fewer stops than the older train. Its popularity was such that the Maritime Express had added so many stops along its route that “the name ‘Express’ began to lose all meaning.”[21] In the summer of 1909, the journey of the Maritime Express from Montreal to Halifax took 28 hours and 15 minutes, compared to 24 hours and 35 minutes for the Ocean Limited. [22]

The Maritime Express operated on a six-day per week schedule for much of its history, originally eschewing Sunday departures in deference to Maritime sensibilities about travel on the Sabbath. In Quebec, where attitudes were apparently more liberal, the train operated daily between Montreal and Mont Joli for many years. With the inauguration of daily service on a year-round Ocean, the Maritime Express would maintain a Monday-Saturday schedule. Traffic volumes continued to grow on both trains to the extent that a third daily-except-Sunday train was added to the schedule in 1927, the all-sleeping car Acadian; however, the train was short-lived, an early casualty of the Great Depression in late 1929.[23]

The train on the bill

In 1912, the Dominion of Canada issued its first five dollar banknote, featuring an engraving of a steam-powered passenger train. The image on the face of the bill is of the Maritime Express traversing Nova Scotia’s Wentworth Valley. The picture closely follows an original publicity photo, shot by an unknown photographer for the ICR, circa 1903. Some later sources identify the train pictured as the Ocean Limited[24]; however, historians Jay Underwood and Douglas Smith both confirm the image is of the Maritime Express. Among other evidence, the same image appears on postcards produced in the first decade of the century that clearly identify the train as the Maritime Express. The locomotive in the photograph is a smaller 4-6-0 type that had been largely replaced by bigger motive power at the time the Ocean Limited was introduced. Over 11 million of the banknotes were produced and they remained in circulation until the early 1930s. [25][26]

Later years

In 1915, as World War I deepened, the federal government moved to consolidate its railway holdings, including the ICR and the Moncton-Winnipeg National Transcontinental Railway, under the umbrella of the Canadian Government Railways (CGR). Despite this, the ICR continued to largely maintain its own brand, including the use of its “IRC” reporting marks and its slogan, “The People’s Railway”. The ongoing financial crisis began to impact other struggling lines and in 1918 the government created Canadian National Railways to take over operations of the CGR and the Canadian Northern Railway, followed by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and its parent, the Grand Trunk.[27] CNR continued to operate the Maritime Express and the Ocean Limited, outfitting the trains with new power in the form of 4-8-2 Mountain-type locomotives and, later, powerful 4-8-4 “Northerns”. During the depths of the Depression, the Ocean Limited lost much of its lustre, becoming as much of a plodding local as its older running mate. Consideration was given briefly to discontinuing the Maritime Express during the economic downturn but the option was rejected.[28]

With the outbreak of World War II, traffic on CNR’s lines to the Atlantic coast soared, resulting in massive improvements to infrastructure and an expansion of passenger service. The trains frequently operated in multiple sections and in 1941 the railway introduced a third daily train, the Scotian, and converted the Ocean to a sleeping-car only train. Wartime traffic continued to stretch capacity to the limit, resulting in the replacement of full dining cars on the Maritime Express with café cars in 1942. The running time for the Maritime Express was extended to almost 31 hours in 1943. That year, the train moved to the long-awaited new Montreal Central Station. [29]

With the end of World War II and the decline in military traffic, ridership on the Maritime Express and its two running mates began to erode. Revenue losses grew, although there were a few bright spots: the Maritime Express continued to show a profit on its Campbellton-Riviere-du-Loup route segment in 1949. The loss of passengers was compounded by the introduction of the first rudimentary interprovincial bus service and expanded air service by Trans-Canada Air Lines. In an effort to arrest the trend, in 1952-53 CNR ordered 359 new passenger cars to replace war-weary rolling stock, including sleepers with more private rooms. In March, 1950, diesel power appeared on the Maritime Express for the first time in the form of a three-unit General Motors EMD FP7 demonstrator; however, the Maritime Express was the last of the three trains to fully convert to diesel power in 1958, mostly in favour of MLW FPA-2 models.[30]

Discontinuance

In 1955, the Maritime Express lost its status as the railroad’s premiere train, giving up the numbers 1 and 2 to the Ocean Limited, which it shared with the newly-inaugurated Vancouver -Toronto/Montreal Super Continental. Following the recommendations of a parliamentary committee established to examine the future of Maritime passenger services, the schedule of the Maritime Express was reduced in 1957 to less than 26 hours eastbound and just over 23 hours westbound, improving connections with the Yarmouth-Halifax train to boost express fish shipments. The new schedule had the train leaving Halifax at 3:10 p.m., changed from 7:45 p.m. Despite the changes, ridership on the train continued to decline, resulting in the removal of sleeping, cafeteria and parlour cars from its consist over parts of the route. On 28 October, 1961, the Maritime Express was cut back to Moncton, no longer travelling between the New Brunswick city and Halifax. The schedule also added a layover of more than five hours in Campbellton. For most of the year, the train carried mostly mail and express cars along with a few coaches.[31]

Efforts by CNR to boost ridership with its innovative “red, white and blue” fare structure and other improvements in the early 1960s failed to produce positive results for the Maritime Express and on 27 October, 1963, the train became a daylight-only train between Montreal and Campbellton. Less than six months later, on 26 April, CNR removed the Maritime Express name from the train.[32]

Accidents

- The Maritime Express operated without a major accident from its inception in 1898 until 5 October, 1909, when the engineer and express handler died after their train collided with a freight train near Campbellton, New Brunswick. The engineer of the freight train was also killed. An inquest blamed improper timekeeping for the freight train’s failure to clear the line in time.

- On 10 July, 1912, the train derailed at Grand Lake, 23 miles from its destination in Halifax. The engineer and fireman died when their locomotive rolled down an embankment into the lake. A kinked rail was blamed for the mishap, which also killed a hobo riding in a baggage car.

- The Ocean Limited was in the siding at Thomson Station, Nova Scotia, on 31 March, 1927, when the Maritime Express, travelling at speed on the main line, went through an open switch and collided with the train. The Ocean’s fireman was killed in the crash.

- The last major incident involving the train occurred on 6 July, 1943, at the height of heavy World War II traffic. The westbound Maritime Express, with 15 cars, collided with a 42-car freight train on the bridge spanning the Montmagny River in Quebec. The investigation found that the passenger train’s engineer had seen the approaching freight in time to nearly stop his train, but the engineer of the freight train inexplicably applied his brakes only moments before impact. He died in the wreck. [33]

References

- ↑ Seton, L.A. (1958, March). The Intercolonial Railway: Part one – Genesis of the project. Canadian Railway Historical Association News Report, 87, 31-38. Retrieved from https://www.exporail.org/can_rail/Canadian%20Rail_no087_1958.pdf

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2005). Built for war: Canada’s Intercolonial Railway. Pickering ON: Railfare

- ↑ Underwood, Ibid

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 J. Boyko (March 27, 2017). "Intercolonial Railway". The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/intercolonial-railway. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ↑ Creet, M. (2003).Fleming, Sir Sandford. In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved from [www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fleming_sandford_14E.html Fleming]

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2005). Built for war: Canada’s Intercolonial Railway. Pickering ON: Railfare-DC Books.

- ↑ Marsh, J. J. (2015): Railway history, at The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed September 3, 2019. dated March 4, 2015

- ↑ Intercolonial Railway-1876 (2001). Canadian Rail (483), pp. 111-129.

- ↑ Underwood., J. (2010). A line through the hills: How the Intercolonial Railway crossed Nova Scotia’s Cobequid Mountains. Halifax: Pennydreadful.

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Starting in August, 1877. Before that, Halifax trains stopped at the station built in 1854 by the Nova Scotia Railway at Richmond. Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2005). Built for war: Canada’s Intercolonial Railway. Pickering ON: Railfare

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Underwood, J. (n.d.). A train runs through it. Saltscapes. Retrieved from http://www.saltscapes.com/roots-folks/628-a-train-runs-through-it.html

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2004). The creation of a legend. Canadian Rail (500), p. 92.

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Canada Currency (n.d.). Dominion of Canada May 1st 1912 Five Dollar Bill. Retrieved from: http://canadacurrency.com/dominion-of-canada/five-dollar-bank-notes-dominion-of-canada/value-of-may-1st-1912-5-bill-from-the-dominion-of-canada-2/

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2010). History follows the Ocean to the ocean. Canadian Rail (536), pp. 95-106.

- ↑ Underwood, J. (2005). Built for war: Canada’s Intercolonial Railway. Pickering ON: Railfare

- ↑ Smith, D.N.W. (2004). The Ocean Limited: A centennial tribute. Ottawa: Trackside Canada.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ A nameless train carrying the Maritime Express’ final numbers – 3 and 4 – would continue to run between Montreal and Campbellton until 1966. Smith, Ibid.

- ↑ Smith, Ibid.