Physics:Microrheology

Microrheology[1] is a technique used to measure the rheological properties of a medium, such as microviscosity, via the measurement of the trajectory of a flow tracer (a micrometre-sized particle). It is a new way of doing rheology, traditionally done using a rheometer. There are two types of microrheology: passive microrheology and active microrheology. Passive microrheology uses inherent thermal energy to move the tracers, whereas active microrheology uses externally applied forces, such as from a magnetic field or an optical tweezer, to do so. Microrheology can be further differentiated into 1- and 2-particle methods.[2] [3]

Passive microrheology

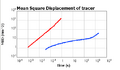

Passive microrheology uses the thermal energy (kT) to move the tracers, although recent evidence suggests that active random forces inside cells may instead move the tracers in a diffusive-like manner.[4] The trajectories of the tracers are measured optically either by microscopy, or alternatively by light scattering techniques. Diffusing-wave spectroscopy (DWS) is a common choice that extends light scattering measurement techniques to account for multiple scattering events.[5] From the mean squared displacement with respect to time (noted MSD or <Δr2> ), one can calculate the visco-elastic moduli G′(ω) and G″(ω) using the generalized Stokes–Einstein relation (GSER). Here is a view of the trajectory of a particle of micrometer size.

In a standard passive microrheology test, the movement of dozens of tracers is tracked in a single video frame. The motivation is to average the movements of the tracers and calculate a robust MSD profile.

Observing the MSD for a wide range of integration time scales (or frequencies) gives information on the microstructure of the medium where are diffusing the tracers.

If the tracers are experiencing free diffusion in a purely viscous material, the MSD should grow linearly with sampling integration time:

[math]\displaystyle{ \langle \Delta r^2\rangle=4Dt }[/math].

If the tracers are moving in a spring-like fashion within a purely elastic material, the MSD should have no time dependence:

[math]\displaystyle{ \langle \Delta r^2\rangle=\text{Const} }[/math]

In most cases the tracers are presenting a sub-linear integration-time dependence, indicating the medium has intermediate viscoelastic properties. Of course, the slope changes in different time scales, as the nature of the response from the material is frequency dependent.

Microrheology is another way to do linear rheology. Since the force involved is very weak (order of 10−15 N), microrheology is guaranteed to be in the so-called linear region of the strain/stress relationship. It is also able to measure very small volumes (biological cell).

Given the complex viscoelastic modulus [math]\displaystyle{ G(\omega)=G'(\omega)+i G''(\omega)\, }[/math] with G′(ω) the elastic (conservative) part and G″(ω) the viscous (dissipative) part and ω=2πf the pulsation. The GSER is as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{G}(s)=\frac{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}{\pi a s \langle\Delta \tilde{r}^{2}(s)\rangle} }[/math]

with

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{G}(s) }[/math]: Laplace transform of G

- kB: Boltzmann constant

- T: temperature in kelvins

- s: the Laplace frequency

- a: the radius of the tracer

- [math]\displaystyle{ \langle\Delta \tilde{r}^{2}(s)\rangle }[/math]: the Laplace transform of the mean squared displacement

A related method of passive microrheology involves the tracking positions of a particle at high frequency, often with a quadrant photodiode.[6] From the position, [math]\displaystyle{ x(t) }[/math], the power spectrum, [math]\displaystyle{ \langle x_{\omega}^2\rangle }[/math] can be found, and then related to the real and imaginary parts of the response function, [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha(\omega) }[/math].[7] The response function leads directly to a calculation of the complex shear modulus, [math]\displaystyle{ G(\omega) }[/math] via:

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(\omega) = \frac{1}{6 \pi a \alpha(\omega)} }[/math]

Two Point Microrheology[8]

There could be many artifacts that change the values measured by the passive microrheology tests, resulting in a disagreement between microrheology and normal rheology. These artifacts include tracer-matrix interactions, tracer-matrix size mismatch and more.

A different microrheological approach studies the cross-correlation of two tracers in the same sample. In practice, instead of measuring the MSD [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \Delta r^2\rangle }[/math], movements of two distinct particles are measured - [math]\displaystyle{ \langle\Delta r_1 \Delta r_2\rangle }[/math]. Calculating the G(ω) of the medium between the tracers follows:

[math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{G}(s)=\frac{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}{2\pi R s \langle\Delta \tilde{r}_1(s)\Delta \tilde{r}_2(s)\rangle} }[/math]

Notice this equation does not depend on a, but instead in depends on R - the distance between the tracers (assuming R>>a).

Some studies has shown that this method is better in coming to agreement with standard rheological measurements (in the relevant frequencies and materials)

Active microrheology

Active microrheology may use a magnetic field ,[9][10][11][8][12] [13] optical tweezers[14] [15] [16] [17][18] or an atomic force microscope[19] to apply a force on the tracer and then find the stress/strain relation.

The force applied is a sinusoidal force with amplitude A and frequency ω -

[math]\displaystyle{ F=A \sin(\omega t) }[/math]

The response of the tracer is a factor of the matrix visco-elastic nature. If a matrix is totally elastic (a solid), the response to the acting force should be immediate and the tracers should be observed moving by-

[math]\displaystyle{ X_e=B \sin(\omega t) }[/math].

with [math]\displaystyle{ A/B = G(\omega) }[/math].

On the other hand, if the matrix is totally viscous (a liquid), there should be a phase shift of [math]\displaystyle{ 90^o }[/math] between the strain and the stress -

[math]\displaystyle{ X_v=B \sin(\omega t + 90^o) = B\cos(\omega t) }[/math]

in reality, as most materials are visco-elastic, the phase shift observed is [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \varphi\lt 90 }[/math].

When φ>45 the matrix is considered mostly in its "viscous domain" and when φ<45 the matrix is considered mostly in its "elastic domain".

Given a measured response phase shift φ (sometimes noted as δ), this ratio applies:

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{G''}{G'}=\frac{\frac{A}{B}\sin(\varphi)}{\frac{A}{B}\cos(\varphi)}=\tan(\varphi) }[/math]

Similar response phase analysis is used in regular rheology testing.

More recently, it has been developed into Force spectrum microscopy to measure contributions of random active motor proteins to diffusive motion in the cytoskeleton.[4]

References

- ↑ Mason, Thomas G.; Weitz, David A. (1995). "Optical Measurements of Frequency-Dependent Linear Viscoelastic Moduli of Complex Fluids". Physical Review Letters 74 (7): 1250–1253. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.74.1250. PMID 10058972. Bibcode: 1995PhRvL..74.1250M.

- ↑ Crocker, John C.; Valentine, M. T.; Weeks, Eric R.; Gisler, T. et al. (2000). "Two-Point Microrheology of Inhomogeneous Soft Materials". Physical Review Letters 85 (4): 888–891. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.888. PMID 10991424. Bibcode: 2000PhRvL..85..888C. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-opus-53924.

- ↑ Levine, Alex J.; Lubensky, T. C. (2000). "One- and Two-Particle Microrheology". Physical Review Letters 85 (8): 1774–1777. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1774. PMID 10970611. Bibcode: 2000PhRvL..85.1774L.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Guo, Ming (2014). "Probing the Stochastic, Motor-Driven Properties of the Cytoplasm Using Force Spectrum Microscopy". Cell 158 (4): 822–832. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.051. PMID 25126787.

- ↑ Furst, Eric M.; Todd M. Squires (2017). Microrheology (First ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-965520-5. OCLC 990115841.

- ↑ Schnurr, B.; Gittes, F.; MacKintosh, F. C.; Schmidt, C. F. (1997). "Determining Microscopic Viscoelasticity in Flexible and Semiflexible Polymer Networks from Thermal Fluctuations". Macromolecules 30 (25): 7781–7792. doi:10.1021/ma970555n. Bibcode: 1997MaMol..30.7781S.

- ↑ Gittes, F.; Schnurr, B.; Olmsted, P. D.; MacKintosh, F. C. et al. (1997). "Determining Microscopic Viscoelasticity in Flexible and Semiflexible Polymer Networks from Thermal Fluctuations". Physical Review Letters 79 (17): 3286–3289. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.3286. Bibcode: 1997PhRvL..79.3286G.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Weitz, D. A., John C. Crocker (2000). "Two-Point Microrheology of Inhomogeneous Soft Materials". Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (4): 888–891. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.888. PMID 10991424. Bibcode: 2000PhRvL..85..888C. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-opus-53924.

- ↑ A.R. Bausch (1999). "Measurement of local viscoelasticity and forces in living cells by magnetic tweezers". Biophysical Journal 76 (1 Pt 1): 573–9. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77225-5. PMID 9876170. Bibcode: 1999BpJ....76..573B.

- ↑ K.S. Zaner; P.A. Valberg (1989). "Viscoelasticity of F-actin measured with magnetic microparticles". Journal of Cell Biology 109 (5): 2233–43. doi:10.1083/jcb.109.5.2233. PMID 2808527.

- ↑ F.Ziemann; J. Radler; E. Sackmann (1994). "Local measurements of viscoelastic moduli of entangled actin networks using an oscillating magnetic bead micro-rheometer". Biophysical Journal 66 (6): 2210–6. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(94)81017-3. PMID 8075354. Bibcode: 1994BpJ....66.2210Z.

- ↑ F. Amblard (1996). "Subdiffusion and Anomalous Local Viscoelasticity in Actin Networks". Physical Review Letters 77 (21): 4470–4473. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.4470. PMID 10062546. Bibcode: 1996PhRvL..77.4470A.

- ↑ Manlio Tassieri (2010). "Analysis of the linear viscoelasticity of polyelectrolytes by magnetic microrheometry—Pulsed creep experiments and the one particle response". Journal of Rheology 54 (1): 117–131. doi:10.1122/1.3266946. Bibcode: 2010JRheo..54..117T.

- ↑ E. Helfer (2000). "Microrheology of Biopolymer-Membrane Complexes". Physical Review Letters 85 (2): 457–60. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.457. PMID 10991307. Bibcode: 2000PhRvL..85..457H. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01960753/file/PRL2000_Helfer%26al.pdf.

- ↑ Manlio Tassieri (2009). "Measuring storage and loss moduli using optical tweezers: Broadband microrheology". Phys. Rev. E 81 (2): 026308. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.81.026308. PMID 20365652. Bibcode: 2010PhRvE..81b6308T.

- ↑ Daryl Preece (2011). "Optical tweezers: wideband microrheology". Journal of Optics 13 (11): 044022. doi:10.1088/2040-8978/13/4/044022. Bibcode: 2011JOpt...13d4022P.

- ↑ Manlio Tassieri (2012). "Microrheology with optical tweezers: data analysis". New Journal of Physics 14 (11): 115032. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/14/11/115032. Bibcode: 2012NJPh...14k5032T.

- ↑ David Engström; Michael C.M. Varney; Martin Persson; Rahul P. Trivedi et al. (2012). "Unconventional structure-assisted optical manipulation of high-index nanowires in liquid crystals". Optics Express 20 (7): 7741–7748. doi:10.1364/OE.20.007741. PMID 22453452. Bibcode: 2012OExpr..20.7741E.

- ↑ Rigato, Annafrancesca; Miyagi, Atsushi; Scheuring, Simon; Rico, Felix (2017-05-01). "High-frequency microrheology reveals cytoskeleton dynamics in living cells" (in en). Nature Physics advance online publication (8): 771–775. doi:10.1038/nphys4104. ISSN 1745-2481. PMID 28781604. Bibcode: 2017NatPh..13..771R.

External links

- Harvard Weitz Lab page

- Review of microrheology in optical tweezers

- Review on microrheology

- Illustrated description of microrheology and a microrheology analysis, with movies

- DWS Microrheology Overview

|