*-algebra

In mathematics, and more specifically in abstract algebra, a *-algebra (or involutive algebra; read as "star-algebra") is a mathematical structure consisting of two involutive rings R and A, where R is commutative and A has the structure of an associative algebra over R. Involutive algebras generalize the idea of a number system equipped with conjugation, for example the complex numbers and complex conjugation, matrices over the complex numbers and conjugate transpose, and linear operators over a Hilbert space and Hermitian adjoints. However, it may happen that an algebra admits no involution.[lower-alpha 1]

Definitions

*-ring

| Algebraic structure → Ring theory Ring theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, a *-ring is a ring with a map * : A → A that is an antiautomorphism and an involution.

More precisely, * is required to satisfy the following properties:[1]

- (x + y)* = x* + y*

- (x y)* = y* x*

- 1* = 1

- (x*)* = x

for all x, y in A.

This is also called an involutive ring, involutory ring, and ring with involution. The third axiom is implied by the second and fourth axioms, making it redundant.

Elements such that x* = x are called self-adjoint.[2]

Archetypical examples of a *-ring are fields of complex numbers and algebraic numbers with complex conjugation as the involution. One can define a sesquilinear form over any *-ring.

Also, one can define *-versions of algebraic objects, such as ideal and subring, with the requirement to be *-invariant: x ∈ I ⇒ x* ∈ I and so on.

*-rings are unrelated to star semirings in the theory of computation.

*-algebra

A *-algebra A is a *-ring,[lower-alpha 2] with involution * that is an associative algebra over a commutative *-ring R with involution ′, such that (r x)* = r′ x* ∀r ∈ R, x ∈ A.[3]

The base *-ring R is often the complex numbers (with ′ acting as complex conjugation).

It follows from the axioms that * on A is conjugate-linear in R, meaning

- (λ x + μ y)* = λ′ x* + μ′ y*

for λ, μ ∈ R, x, y ∈ A.

A *-homomorphism f : A → B is an algebra homomorphism that is compatible with the involutions of A and B, i.e.,

- f(a*) = f(a)* for all a in A.[2]

Philosophy of the *-operation

The *-operation on a *-ring is analogous to complex conjugation on the complex numbers. The *-operation on a *-algebra is analogous to taking adjoints in complex matrix algebras.

Notation

The * involution is a unary operation written with a postfixed star glyph centered above or near the mean line:

- x ↦ x*, or

- x ↦ x∗ (TeX:

x^*),

but not as "x∗"; see the asterisk article for details.

Examples

- Any commutative ring becomes a *-ring with the trivial (identical) involution.

- The most familiar example of a *-ring and a *-algebra over reals is the field of complex numbers C where * is just complex conjugation.

- More generally, a field extension made by adjunction of a square root (such as the imaginary unit √−1) is a *-algebra over the original field, considered as a trivially-*-ring. The * flips the sign of that square root.

- A quadratic integer ring (for some D) is a commutative *-ring with the * defined in the similar way; quadratic fields are *-algebras over appropriate quadratic integer rings.

- Quaternions, split-complex numbers, dual numbers, and possibly other hypercomplex number systems form *-rings (with their built-in conjugation operation) and *-algebras over reals (where * is trivial). None of the three is a complex algebra.

- Hurwitz quaternions form a non-commutative *-ring with the quaternion conjugation.

- The matrix algebra of n × n matrices over R with * given by the transposition.

- The matrix algebra of n × n matrices over C with * given by the conjugate transpose.

- Its generalization, the Hermitian adjoint in the algebra of bounded linear operators on a Hilbert space also defines a *-algebra.

- The polynomial ring R[x] over a commutative trivially-*-ring R is a *-algebra over R with P *(x) = P (−x).

- If (A, +, ×, *) is simultaneously a *-ring, an algebra over a ring R (commutative), and (r x)* = r (x*) ∀r ∈ R, x ∈ A, then A is a *-algebra over R (where * is trivial).

- As a partial case, any *-ring is a *-algebra over integers.

- Any commutative *-ring is a *-algebra over itself and, more generally, over any its *-subring.

- For a commutative *-ring R, its quotient by any its *-ideal is a *-algebra over R.

- For example, any commutative trivially-*-ring is a *-algebra over its dual numbers ring, a *-ring with non-trivial *, because the quotient by ε = 0 makes the original ring.

- The same about a commutative ring K and its polynomial ring K[x]: the quotient by x = 0 restores K.

- In Hecke algebra, an involution is important to the Kazhdan–Lusztig polynomial.

- The endomorphism ring of an elliptic curve becomes a *-algebra over the integers, where the involution is given by taking the dual isogeny. A similar construction works for abelian varieties with a polarization, in which case it is called the Rosati involution (see Milne's lecture notes on abelian varieties).

Involutive Hopf algebras are important examples of *-algebras (with the additional structure of a compatible comultiplication); the most familiar example being:

- The group Hopf algebra: a group ring, with involution given by g ↦ g−1.

Non-Example

Not every algebra admits an involution:

Regard the 2×2 matrices over the complex numbers. Consider the following subalgebra:

Any nontrivial antiautomorphism necessarily has the form:[4] for any complex number .

It follows that any nontrivial antiautomorphism fails to be involutive:

Concluding that the subalgebra admits no involution.

Additional structures

Many properties of the transpose hold for general *-algebras:

- The Hermitian elements form a Jordan algebra;

- The skew Hermitian elements form a Lie algebra;

- If 2 is invertible in the *-ring, then the operators 1/2(1 + *) and 1/2(1 − *) are orthogonal idempotents,[2] called symmetrizing and anti-symmetrizing, so the algebra decomposes as a direct sum of modules (vector spaces if the *-ring is a field) of symmetric and anti-symmetric (Hermitian and skew Hermitian) elements. These spaces do not, generally, form associative algebras, because the idempotents are operators, not elements of the algebra.

Skew structures

Given a *-ring, there is also the map −* : x ↦ −x*. It does not define a *-ring structure (unless the characteristic is 2, in which case −* is identical to the original *), as 1 ↦ −1, neither is it antimultiplicative, but it satisfies the other axioms (linear, involution) and hence is quite similar to *-algebra where x ↦ x*.

Elements fixed by this map (i.e., such that a = −a*) are called skew Hermitian.

For the complex numbers with complex conjugation, the real numbers are the Hermitian elements, and the imaginary numbers are the skew Hermitian.

See also

- Semigroup with involution

- B*-algebra

- C*-algebra

- Dagger category

- von Neumann algebra

- Baer ring

- Operator algebra

- Conjugate (algebra)

- Cayley–Dickson construction

- Composition algebra

Notes

References

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. (2015). "C-Star Algebra". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/C-Star-Algebra.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Baez, John (2015). "Octonions". University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150326133405/http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/octonions/node5.html. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ star-algebra in nLab

- ↑ Winker, S. K.; Wos, L.; Lusk, E. L. (1981). "Semigroups, Antiautomorphisms, and Involutions: A Computer Solution to an Open Problem, I". Mathematics of Computation 37 (156): 533–545. doi:10.2307/2007445. ISSN 0025-5718. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2007445.

In mathematical analysis and in probability theory, a σ-algebra ("sigma algebra") is part of the formalism for defining sets that can be measured. In calculus and analysis, for example, σ-algebras are used to define the concept of sets with area or volume. In probability theory, they are used to define events with a well-defined probability. In this way, σ-algebras help to formalize the notion of size.

In formal terms, a σ-algebra (also σ-field, where the σ comes from the German "Summe",[1] meaning "sum") on a set is a nonempty collection of subsets of closed under complement, countable unions, and countable intersections. The ordered pair is called a measurable space.

The set is understood to be an ambient space (such as the 2D plane or the set of outcomes when rolling a six-sided die {1,2,3,4,5,6}), and the collection is a choice of subsets declared to have a well-defined size. The closure requirements for σ-algebras are designed to capture our intuitive ideas about how sizes combine: if there is a well-defined probability that an event occurs, there should be a well-defined probability that it does not occur (closure under complements); if several sets have a well-defined size, so should their combination (countable unions); if several events have a well-defined probability of occurring, so should the event where they all occur simultaneously (countable intersections).

The definition of σ-algebra resembles other mathematical structures such as a topology (which is required to be closed under all unions but only finite intersections, and which doesn't necessarily contain all complements of its sets) or a set algebra (which is closed only under finite unions and intersections).

Examples of σ-algebras

If one possible σ-algebra on is where is the empty set. In general, a finite algebra is always a σ-algebra.

If is a countable partition of then the collection of all unions of sets in the partition (including the empty set) is a σ-algebra.

A more useful example is the set of subsets of the real line formed by starting with all open intervals and adding in all countable unions, countable intersections, and relative complements and continuing this process (by transfinite iteration through all countable ordinals) until the relevant closure properties are achieved (a construction known as the Borel hierarchy).

Motivation

There are at least three key motivators for σ-algebras: defining measures, manipulating limits of sets, and managing partial information characterized by sets.

Measure

A measure on is a function that assigns a non-negative real number to subsets of this can be thought of as making precise a notion of "size" or "volume" for sets. We want the size of the union of disjoint sets to be the sum of their individual sizes, even for an infinite sequence of disjoint sets.

One would like to assign a size to every subset of but in many natural settings, this is not possible. For example, the axiom of choice implies that when the size under consideration is the ordinary notion of length for subsets of the real line, then there exist sets for which no size exists, for example, the Vitali sets. For this reason, one considers instead a smaller collection of privileged subsets of These subsets will be called the measurable sets. They are closed under operations that one would expect for measurable sets, that is, the complement of a measurable set is a measurable set and the countable union of measurable sets is a measurable set. Non-empty collections of sets with these properties are called σ-algebras.

Limits of sets

Many uses of measure, such as the probability concept of almost sure convergence, involve limits of sequences of sets. For this, closure under countable unions and intersections is paramount. Set limits are defined as follows on σ-algebras.

- The limit supremum or outer limit of a sequence of subsets of is It consists of all points that are in infinitely many of these sets (or equivalently, that are in cofinally many of them). That is, if and only if there exists an infinite subsequence (where ) of sets that all contain that is, such that

- The limit infimum or inner limit of a sequence of subsets of is It consists of all points that are in all but finitely many of these sets (or equivalently, that are eventually in all of them). That is, if and only if there exists an index such that all contain that is, such that

The inner limit is always a subset of the outer limit: If these two sets are equal then their limit exists and is equal to this common set:

Sub σ-algebras

In much of probability, especially when conditional expectation is involved, one is concerned with sets that represent only part of all the possible information that can be observed. This partial information can be characterized with a smaller σ-algebra which is a subset of the principal σ-algebra; it consists of the collection of subsets relevant only to and determined only by the partial information. Formally, if are σ-algebras on , then is a sub σ-algebra of if .

The Bernoulli process provides a simple example. This consists of a sequence of random coin flips, coming up Heads () or Tails (), of unbounded length. The sample space Ω consists of all possible infinite sequences of or

The full sigma algebra can be generated from an ascending sequence of subalgebras, by considering the information that might be obtained after observing some or all of the first coin flips. This sequence of subalgebras is given by Each of these is finer than the last, and so can be ordered as a filtration

The first subalgebra is the trivial algebra: it has only two elements in it, the empty set and the total space. The second subalgebra has four elements: the two in plus two more: sequences that start with and sequences that start with . Each subalgebra is finer than the last. The 'th subalgebra contains elements: it divides the total space into all of the possible sequences that might have been observed after flips, including the possible non-observation of some of the flips.

The limiting algebra is the smallest σ-algebra containing all the others. It is the algebra generated by the product topology or weak topology on the product space

Definition and properties

Definition

Let be some set, and let represent its power set, the set of all subsets of . Then a subset is called a σ-algebra if it satisfies the following three properties:[2]

- is in .

- is closed under complementation: If some set is in then so is its complement,

- is closed under countable unions: If are in then so is

From these properties, it follows that the σ-algebra is also closed under countable intersections (by applying De Morgan's laws).

It also follows that the empty set is in since by (1) is in and (2) asserts that its complement, the empty set, is also in Moreover, since satisfies all 3 conditions, it follows that is the smallest possible σ-algebra on The largest possible σ-algebra on is

Elements of the σ-algebra are called measurable sets. An ordered pair where is a set and is a σ-algebra over is called a measurable space. A function between two measurable spaces is called a measurable function if the preimage of every measurable set is measurable. The collection of measurable spaces forms a category, with the measurable functions as morphisms. Measures are defined as certain types of functions from a σ-algebra to

A σ-algebra is both a π-system and a Dynkin system (λ-system). The converse is true as well, by Dynkin's theorem (see below).

Dynkin's π-λ theorem

This theorem (or the related monotone class theorem) is an essential tool for proving many results about properties of specific σ-algebras. It capitalizes on the nature of two simpler classes of sets, namely the following.

- A π-system is a collection of subsets of that is closed under finitely many intersections, and

- A Dynkin system (or λ-system) is a collection of subsets of that contains and is closed under complement and under countable unions of disjoint subsets.

Dynkin's π-λ theorem says, if is a π-system and is a Dynkin system that contains then the σ-algebra generated by is contained in Since certain π-systems are relatively simple classes, it may not be hard to verify that all sets in enjoy the property under consideration while, on the other hand, showing that the collection of all subsets with the property is a Dynkin system can also be straightforward. Dynkin's π-λ Theorem then implies that all sets in enjoy the property, avoiding the task of checking it for an arbitrary set in

One of the most fundamental uses of the π-λ theorem is to show equivalence of separately defined measures or integrals. For example, it is used to equate a probability for a random variable with the Lebesgue-Stieltjes integral typically associated with computing the probability: for all in the Borel σ-algebra on where is the cumulative distribution function for defined on while is a probability measure, defined on a σ-algebra of subsets of some sample space

Combining σ-algebras

Suppose is a collection of σ-algebras on a space

Meet

The intersection of a collection of σ-algebras is a σ-algebra. To emphasize its character as a σ-algebra, it often is denoted by:

Sketch of Proof: Let denote the intersection. Since is in every is not empty. Closure under complement and countable unions for every implies the same must be true for Therefore, is a σ-algebra.

Join

The union of a collection of σ-algebras is not generally a σ-algebra, or even an algebra, but it generates a σ-algebra known as the join which typically is denoted A π-system that generates the join is Sketch of Proof: By the case it is seen that each so This implies by the definition of a σ-algebra generated by a collection of subsets. On the other hand, which, by Dynkin's π-λ theorem, implies

σ-algebras for subspaces

Suppose is a subset of and let be a measurable space.

- The collection is a σ-algebra of subsets of

- Suppose is a measurable space. The collection is a σ-algebra of subsets of

Relation to σ-ring

A σ-algebra is just a σ-ring that contains the universal set [3] A σ-ring need not be a σ-algebra, as for example measurable subsets of zero Lebesgue measure in the real line are a σ-ring, but not a σ-algebra since the real line has infinite measure and thus cannot be obtained by their countable union. If, instead of zero measure, one takes measurable subsets of finite Lebesgue measure, those are a ring but not a σ-ring, since the real line can be obtained by their countable union yet its measure is not finite.

Typographic note

σ-algebras are sometimes denoted using calligraphic capital letters, or the Fraktur typeface. Thus may be denoted as or

Particular cases and examples

Separable σ-algebras

A separable -algebra (or separable -field) is a -algebra that is a separable space when considered as a metric space with metric for and a given finite measure (and with being the symmetric difference operator).[4] Any -algebra generated by a countable collection of sets is separable, but the converse need not hold. For example, the Lebesgue -algebra is separable (since every Lebesgue measurable set is equivalent to some Borel set) but not countably generated (since its cardinality is higher than continuum).

A separable measure space has a natural pseudometric that renders it separable as a pseudometric space. The distance between two sets is defined as the measure of the symmetric difference of the two sets. The symmetric difference of two distinct sets can have measure zero; hence the pseudometric as defined above need not be a true metric. However, if sets whose symmetric difference has measure zero are identified into a single equivalence class, the resulting quotient set can be properly metrized by the induced metric. If the measure space is separable, it can be shown that the corresponding metric space is, too.

Simple set-based examples

Let be any set.

- The family consisting only of the empty set and the set called the minimal or trivial σ-algebra over

- The power set of called the discrete σ-algebra.

- The collection is a simple σ-algebra generated by the subset

- The collection of subsets of which are countable or whose complements are countable is a σ-algebra (which is distinct from the power set of if and only if is uncountable). This is the σ-algebra generated by the singletons of Note: "countable" includes finite or empty.

- The collection of all unions of sets in a countable partition of is a σ-algebra.

Stopping time sigma-algebras

A stopping time can define a -algebra the so-called stopping time sigma-algebra, which in a filtered probability space describes the information up to the random time in the sense that, if the filtered probability space is interpreted as a random experiment, the maximum information that can be found out about the experiment from arbitrarily often repeating it until the time is [5]

σ-algebras generated by families of sets

σ-algebra generated by an arbitrary family

Let be an arbitrary family of subsets of Then there exists a unique smallest σ-algebra which contains every set in (even though may or may not itself be a σ-algebra). It is, in fact, the intersection of all σ-algebras containing (See intersections of σ-algebras above.) This σ-algebra is denoted and is called the σ-algebra generated by

If is empty, then Otherwise consists of all the subsets of that can be made from elements of by a countable number of complement, union and intersection operations.

For a simple example, consider the set Then the σ-algebra generated by the single subset is By an abuse of notation, when a collection of subsets contains only one element, may be written instead of in the prior example instead of Indeed, using to mean is also quite common.

There are many families of subsets that generate useful σ-algebras. Some of these are presented here.

σ-algebra generated by a function

If is a function from a set to a set and is a -algebra of subsets of then the -algebra generated by the function denoted by is the collection of all inverse images of the sets in That is,

A function from a set to a set is measurable with respect to a σ-algebra of subsets of if and only if is a subset of

One common situation, and understood by default if is not specified explicitly, is when is a metric or topological space and is the collection of Borel sets on

If is a function from to then is generated by the family of subsets which are inverse images of intervals/rectangles in

A useful property is the following. Assume is a measurable map from to and is a measurable map from to If there exists a measurable map from to such that for all then If is finite or countably infinite or, more generally, is a standard Borel space (for example, a separable complete metric space with its associated Borel sets), then the converse is also true.[6] Examples of standard Borel spaces include with its Borel sets and with the cylinder σ-algebra described below.

Borel and Lebesgue σ-algebras

An important example is the Borel algebra over any topological space: the σ-algebra generated by the open sets (or, equivalently, by the closed sets). This σ-algebra is not, in general, the whole power set. For a non-trivial example that is not a Borel set, see the Vitali set or Non-Borel sets.

On the Euclidean space another σ-algebra is of importance: that of all Lebesgue measurable sets. This σ-algebra contains more sets than the Borel σ-algebra on and is preferred in integration theory, as it gives a complete measure space.

Product σ-algebra

Let and be two measurable spaces. The σ-algebra for the corresponding product space is called the product σ-algebra and is defined by

Observe that is a π-system.

The Borel σ-algebra for is generated by half-infinite rectangles and by finite rectangles. For example,

For each of these two examples, the generating family is a π-system.

σ-algebra generated by cylinder sets

Suppose

is a set of real-valued functions. Let denote the Borel subsets of A cylinder subset of is a finitely restricted set defined as

Each is a π-system that generates a σ-algebra Then the family of subsets is an algebra that generates the cylinder σ-algebra for This σ-algebra is a subalgebra of the Borel σ-algebra determined by the product topology of restricted to

An important special case is when is the set of natural numbers and is a set of real-valued sequences. In this case, it suffices to consider the cylinder sets for which is a non-decreasing sequence of σ-algebras.

Ball σ-algebra

The ball σ-algebra is the smallest σ-algebra containing all the open (and/or closed) balls. This is never larger than the Borel σ-algebra. Note that the two σ-algebra are equal for separable spaces. For some nonseparable spaces, some maps are ball measurable even though they are not Borel measurable, making use of the ball σ-algebra useful in the analysis of such maps.[7]

σ-algebra generated by random variable or vector

Suppose is a probability space. If is measurable with respect to the Borel σ-algebra on then is called a random variable () or random vector (). The σ-algebra generated by is

σ-algebra generated by a stochastic process

Suppose is a probability space and is the set of real-valued functions on If is measurable with respect to the cylinder σ-algebra (see above) for then is called a stochastic process or random process. The σ-algebra generated by is the σ-algebra generated by the inverse images of cylinder sets.

See also

- Measurable function – Function for which the preimage of a measurable set is measurable

- Sample space – Set of all possible outcomes or results of a statistical trial or experiment

- Sigma-additive set function – Mapping function

- Sigma-ring – Ring closed under countable unions

References

- ↑ Elstrodt, J. (2018). Maß- Und Integrationstheorie. Springer Spektrum Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-57939-8

- ↑ Rudin, Walter (1987). Real & Complex Analysis. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054234-1.

- ↑ Vestrup, Eric M. (2009). The Theory of Measures and Integration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-470-31795-2.

- ↑ Džamonja, Mirna; Kunen, Kenneth (1995). "Properties of the class of measure separable compact spaces". Fundamenta Mathematicae: 262. https://archive.uea.ac.uk/~h020/fundamenta.pdf. "If is a Borel measure on the measure algebra of is the Boolean algebra of all Borel sets modulo -null sets. If is finite, then such a measure algebra is also a metric space, with the distance between the two sets being the measure of their symmetric difference. Then, we say that is separable if and only if this metric space is separable as a topological space.".

- ↑ Fischer, Tom (2013). "On simple representations of stopping times and stopping time sigma-algebras". Statistics and Probability Letters 83 (1): 345–349. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2012.09.024. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spl.2012.09.024.

- ↑ Kallenberg, Olav (2001). Foundations of Modern Probability (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 7. ISBN 0-387-95313-2.

- ↑ van der Vaart, A. W., & Wellner, J. A. (1996). Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes. In Springer Series in Statistics. Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2545-2

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Algebra of sets", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/a011400

- Sigma Algebra from PlanetMath.

In mathematics, specifically in category theory, F-algebras generalize the notion of algebraic structure. Rewriting the algebraic laws in terms of morphisms eliminates all references to quantified elements from the axioms, and these algebraic laws may then be glued together in terms of a single functor F, the signature.

F-algebras can also be used to represent data structures used in programming, such as lists and trees.

The main related concepts are initial F-algebras which may serve to encapsulate the induction principle, and the dual construction F-coalgebras.

Definition

If is a category, and is an endofunctor of , then an -algebra is a tuple , where is an object of and is a -morphism . The object is called the carrier of the algebra. When it is permissible from context, algebras are often referred to by their carrier only instead of the tuple.

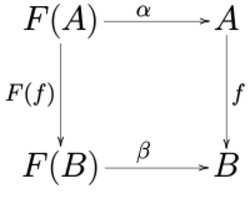

A homomorphism from an -algebra to an -algebra is a -morphism such that , according to the following commutative diagram:

Equipped with these morphisms, -algebras constitute a category.

The dual construction are -coalgebras, which are objects together with a morphism .

Examples

Groups

Classically, a group is a set with a group law , with , satisfying three axioms: the existence of an identity element, the existence of an inverse for each element of the group, and associativity.

To put this in a categorical framework, first define the identity and inverse as functions (morphisms of the set ) by with , and with . Here denotes the set with one element , which allows one to identify elements with morphisms .

It is then possible to write the axioms of a group in terms of functions (note how the existential quantifier is absent):

- ,

- ,

- .

Then this can be expressed with commutative diagrams:[1][2]

Template:Dark mode invert Template:Dark mode invert Template:Dark mode invert

Now use the coproduct (the disjoint union of sets) to glue the three morphisms in one: according to

Thus a group is an -algebra where is the functor . However the reverse is not necessarily true. Some -algebra where is the functor are not groups.

The above construction is used to define group objects over an arbitrary category with finite products and a terminal object . When the category admits finite coproducts, the group objects are -algebras. For example, finite groups are -algebras in the category of finite sets and Lie groups are -algebras in the category of smooth manifolds with smooth maps.

Algebraic structures

Going one step ahead of universal algebra, most algebraic structures are F-algebras. For example, abelian groups are F-algebras for the same functor F(G) = 1 + G + G×G as for groups, with an additional axiom for commutativity: m∘t = m, where t(x,y) = (y,x) is the transpose on GxG.

Monoids are F-algebras of signature F(M) = 1 + M×M. In the same vein, semigroups are F-algebras of signature F(S) = S×S

Rings, domains and fields are also F-algebras with a signature involving two laws +,•: R×R → R, an additive identity 0: 1 → R, a multiplicative identity 1: 1 → R, and an additive inverse for each element -: R → R. As all these functions share the same codomain R they can be glued into a single signature function 1 + 1 + R + R×R + R×R → R, with axioms to express associativity, distributivity, and so on. This makes rings F-algebras on the category of sets with signature 1 + 1 + R + R×R + R×R.

Alternatively, we can look at the functor F(R) = 1 + R×R in the category of abelian groups. In that context, the multiplication is a homomorphism, meaning m(x + y, z) = m(x,z) + m(y,z) and m(x,y + z) = m(x,y) + m(x,z), which are precisely the distributivity conditions. Therefore, a ring is an F-algebra of signature 1 + R×R over the category of abelian groups which satisfies two axioms (associativity and identity for the multiplication).

When we come to vector spaces and modules, the signature functor includes a scalar multiplication k×E → E, and the signature F(E) = 1 + E + k×E is parametrized by k over the category of fields, or rings.

Algebras over a field can be viewed as F-algebras of signature 1 + 1 + A + A×A + A×A + k×A over the category of sets, of signature 1 + A×A over the category of modules (a module with an internal multiplication), and of signature k×A over the category of rings (a ring with a scalar multiplication), when they are associative and unitary.

Lattice

Not all mathematical structures are F-algebras. For example, a poset P may be defined in categorical terms with a morphism s:P × P → Ω, on a subobject classifier (Ω = {0,1} in the category of sets and s(x,y)=1 precisely when x≤y). The axioms restricting the morphism s to define a poset can be rewritten in terms of morphisms. However, as the codomain of s is Ω and not P, it is not an F-algebra.

However, lattices, which are partial orders in which every two elements have a supremum and an infimum, and in particular total orders, are F-algebras. This is because they can equivalently be defined in terms of the algebraic operations: x∨y = inf(x,y) and x∧y = sup(x,y), subject to certain axioms (commutativity, associativity, absorption and idempotency). Thus they are F-algebras of signature P x P + P x P. It is often said that lattice theory draws on both order theory and universal algebra.

Recurrence

Consider the functor that sends a set to . Here, denotes the category of sets, denotes the usual coproduct given by the disjoint union, and is a terminal object (i.e. any singleton set). Then, the set of natural numbers together with the function —which is the coproduct of the functions and —is an F-algebra.

Initial F-algebra

If the category of F-algebras for a given endofunctor F has an initial object, it is called an initial algebra. The algebra in the above example is an initial algebra. Various finite data structures used in programming, such as lists and trees, can be obtained as initial algebras of specific endofunctors.

Types defined by using least fixed point construct with functor F can be regarded as an initial F-algebra, provided that parametricity holds for the type.[3]

See also Universal algebra.

Terminal F-coalgebra

In a dual way, a similar relationship exists between notions of greatest fixed point and terminal F-coalgebra. These can be used for allowing potentially infinite objects while maintaining strong normalization property.[3] In the strongly normalizing Charity programming language (i.e. each program terminates in it), coinductive data types can be used to achieve surprising results, enabling the definition of lookup constructs to implement such “strong” functions like the Ackermann function.[4]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The vertical arrows without labels in the second diagram must be unique since * is terminal.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, (i,id) and (id,i) are labelled inconsistently with the other diagrams as these morphisms "diagonalise" first.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Philip Wadler: Recursive types for free! University of Glasgow, June 1990. Draft.

- ↑ Robin Cockett: Charitable Thoughts (ps and ps.gz)

References

- Pierce, Benjamin C. (1991). "F-Algebras". Basic Category Theory for Computer Scientists. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-66071-7.

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (1990). Category theory for computing science. New York: Prentice Hall. p. 355. ISBN 0131204866. OCLC 19126000.

External links

- Categorical programming with inductive and coinductive types () by Varmo Vene

- Philip Wadler: Recursive types for free! () University of Glasgow, June 1990. Draft.

- Algebra and coalgebra () from CLiki

- B. Jacobs, J. Rutten: A Tutorial on (Co) Algebras and (Co) Induction. Bulletin of the European Association for Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 62, 1997,

- Understanding F-Algebras () by Bartosz Milewski

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In the mathematical field of functional analysis, a nuclear C*-algebra is a C*-algebra A such that for every C*-algebra B the injective and projective C*-cross norms coincides on the algebraic tensor product A⊗B and the completion of A⊗B with respect to this norm is a C*-algebra. This property was first studied by (Takesaki 1964) under the name "Property T", which is not related to Kazhdan's property T.

Characterizations

Nuclearity admits the following equivalent characterizations:

- The identity map, as a completely positive map, approximately factors through matrix algebras. By this equivalence, nuclearity can be considered a noncommutative analogue of the existence of partitions of unity.

- The enveloping von Neumann algebra is injective.

- It is amenable as a Banach algebra.

- (For separable algebras) It is isomorphic to a C*-subalgebra B of the Cuntz algebra 𝒪2 with the property that there exists a conditional expectation from 𝒪2 to B.

Examples

The commutative unital C* algebra of (real or complex-valued) continuous functions on a compact Hausdorff space as well as the noncommutative unital algebra of n×n real or complex matrices are nuclear.[1]

See also

- Exact C*-algebra

- Injective tensor product

- Nuclear space – Generalization of finite-dimensional Euclidean spaces different from Hilbert spaces

- Projective tensor product

References

- ↑ Argerami, Martin (20 January 2023). Answer to "The C∗ algebras of matrices, continuous functions, measures and matrix-valued measures / continuous functions and their state spaces". Mathematics StackExchange. Stack Exchange.

- Connes, Alain (1976), "Classification of injective factors.", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 104 (1): 73–115, doi:10.2307/1971057, ISSN 0003-486X

- Effros, Edward G.; Ruan, Zhong-Jin (2000), Operator spaces, London Mathematical Society Monographs. New Series, 23, The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853482-2, http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Mathematics/PureMathematics/?ci=9780198534822

- Lance, E. Christopher (1982), "Tensor products and nuclear C*-algebras", Operator algebras and applications, Part I (Kingston, Ont., 1980), Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., 38, Providence, R.I.: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 379–399

- Pisier, Gilles (2003), Introduction to operator space theory, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 294, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-81165-1

- Rørdam, M. (2002), "Classification of nuclear simple C*-algebras", Classification of nuclear C*-algebras. Entropy in operator algebras, Encyclopaedia Math. Sci., 126, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 1–145

- Takesaki, Masamichi (1964), "On the cross-norm of the direct product of C*-algebras", The Tohoku Mathematical Journal, Second Series 16: 111–122, doi:10.2748/tmj/1178243737, ISSN 0040-8735

- Takesaki, Masamichi (2003), "Nuclear C*-algebras", Theory of operator algebras. III, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, 127, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 153–204, ISBN 978-3-540-42913-5

Template:Topological tensor products and nuclear spaces

Warning: Default sort key "Nuclear C-algebra" overrides earlier default sort key "-algebra".

it:C*-algebra#C*-algebra nucleare

- REDIRECT Predictable process

This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (September 2025) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics, the spectrum of a C*-algebra or dual of a C*-algebra A, denoted Â, is the set of unitary equivalence classes of irreducible *-representations of A. A *-representation π of A on a Hilbert space H is irreducible if, and only if, there is no closed subspace K different from H and {0} which is invariant under all operators π(x) with x ∈ A. We implicitly assume that irreducible representation means non-null irreducible representation, thus excluding trivial (i.e. identically 0) representations on one-dimensional spaces. As explained below, the spectrum  is also naturally a topological space; this is similar to the notion of the spectrum of a ring.

One of the most important applications of this concept is to provide a notion of dual object for any locally compact group. This dual object is suitable for formulating a Fourier transform and a Plancherel theorem for unimodular separable locally compact groups of type I and a decomposition theorem for arbitrary representations of separable locally compact groups of type I. The resulting duality theory for locally compact groups is however much weaker than the Tannaka–Krein duality theory for compact topological groups or Pontryagin duality for locally compact abelian groups, both of which are complete invariants. That the dual is not a complete invariant is easily seen as the dual of any finite-dimensional full matrix algebra Mn(C) consists of a single point.

Primitive spectrum

The topology of  can be defined in several equivalent ways. We first define it in terms of the primitive spectrum .

The primitive spectrum of A is the set of primitive ideals Prim(A) of A, where a primitive ideal is the kernel of a non-zero irreducible *-representation. The set of primitive ideals is a topological space with the hull-kernel topology (or Jacobson topology). This is defined as follows: If X is a set of primitive ideals, its hull-kernel closure is

Hull-kernel closure is easily shown to be an idempotent operation, that is

and it can be shown to satisfy the Kuratowski closure axioms. As a consequence, it can be shown that there is a unique topology τ on Prim(A) such that the closure of a set X with respect to τ is identical to the hull-kernel closure of X.

Since unitarily equivalent representations have the same kernel, the map π ↦ ker(π) factors through a surjective map

We use the map k to define the topology on  as follows:

Definition. The open sets of  are inverse images k−1(U) of open subsets U of Prim(A). This is indeed a topology.

The hull-kernel topology is an analogue for non-commutative rings of the Zariski topology for commutative rings.

The topology on  induced from the hull-kernel topology has other characterizations in terms of states of A.

Examples

Commutative C*-algebras

The spectrum of a commutative C*-algebra A coincides with the Gelfand dual of A (not to be confused with the dual A' of the Banach space A). In particular, suppose X is a compact Hausdorff space. Then there is a natural homeomorphism

This mapping is defined by

I(x) is a closed maximal ideal in C(X) so is in fact primitive. For details of the proof, see the Dixmier reference. For a commutative C*-algebra,

The C*-algebra of bounded operators

Let H be a separable infinite-dimensional Hilbert space. L(H) has two norm-closed *-ideals: I0 = {0} and the ideal K = K(H) of compact operators. Thus as a set, Prim(L(H)) = {I0, K}. Now

- {K} is a closed subset of Prim(L(H)).

- The closure of {I0} is Prim(L(H)).

Thus Prim(L(H)) is a non-Hausdorff space.

The spectrum of L(H) on the other hand is much larger. There are many inequivalent irreducible representations with kernel K(H) or with kernel {0}.

Finite-dimensional C*-algebras

Suppose A is a finite-dimensional C*-algebra. It is known A is isomorphic to a finite direct sum of full matrix algebras:

where min(A) are the minimal central projections of A. The spectrum of A is canonically isomorphic to min(A) with the discrete topology. For finite-dimensional C*-algebras, we also have the isomorphism

Other characterizations of the spectrum

The hull-kernel topology is easy to describe abstractly, but in practice for C*-algebras associated to locally compact topological groups, other characterizations of the topology on the spectrum in terms of positive definite functions are desirable.

In fact, the topology on  is intimately connected with the concept of weak containment of representations as is shown by the following:

- Theorem. Let S be a subset of Â. Then the following are equivalent for an irreducible representation π;

- The equivalence class of π in  is in the closure of S

- Every state associated to π, that is one of the form

- with ||ξ|| = 1, is the weak limit of states associated to representations in S.

The second condition means exactly that π is weakly contained in S.

The GNS construction is a recipe for associating states of a C*-algebra A to representations of A. By one of the basic theorems associated to the GNS construction, a state f is pure if and only if the associated representation πf is irreducible. Moreover, the mapping κ : PureState(A) → Â defined by f ↦ πf is a surjective map.

From the previous theorem one can easily prove the following;

- Theorem The mapping

- given by the GNS construction is continuous and open.

The space Irrn(A)

There is yet another characterization of the topology on  which arises by considering the space of representations as a topological space with an appropriate pointwise convergence topology. More precisely, let n be a cardinal number and let Hn be the canonical Hilbert space of dimension n.

Irrn(A) is the space of irreducible *-representations of A on Hn with the point-weak topology. In terms of convergence of nets, this topology is defined by πi → π; if and only if

It turns out that this topology on Irrn(A) is the same as the point-strong topology, i.e. πi → π if and only if

- Theorem. Let Ân be the subset of  consisting of equivalence classes of representations whose underlying Hilbert space has dimension n. The canonical map Irrn(A) → Ân is continuous and open. In particular, Ân can be regarded as the quotient topological space of Irrn(A) under unitary equivalence.

Remark. The piecing together of the various Ân can be quite complicated.

Mackey–Borel structure

is a topological space and thus can also be regarded as a Borel space. A famous conjecture of G. Mackey proposed that a separable locally compact group is of type I if and only if the Borel space is standard, i.e. is isomorphic (in the category of Borel spaces) to the underlying Borel space of a complete separable metric space. Mackey called Borel spaces with this property smooth. This conjecture was proved by James Glimm for separable C*-algebras in the 1961 paper listed in the references below.

Definition. A non-degenerate *-representation π of a separable C*-algebra A is a factor representation if and only if the center of the von Neumann algebra generated by π(A) is one-dimensional. A C*-algebra A is of type I if and only if any separable factor representation of A is a finite or countable multiple of an irreducible one.

Examples of separable locally compact groups G such that C*(G) is of type I are connected (real) nilpotent Lie groups and connected real semi-simple Lie groups. Thus the Heisenberg groups are all of type I. Compact and abelian groups are also of type I.

- Theorem. If A is separable, Â is smooth if and only if A is of type I.

The result implies a far-reaching generalization of the structure of representations of separable type I C*-algebras and correspondingly of separable locally compact groups of type I.

Algebraic primitive spectra

Since a C*-algebra A is a ring, we can also consider the set of primitive ideals of A, where A is regarded algebraically. For a ring an ideal is primitive if and only if it is the annihilator of a simple module. It turns out that for a C*-algebra A, an ideal is algebraically primitive if and only if it is primitive in the sense defined above.

- Theorem. Let A be a C*-algebra. Any algebraically irreducible representation of A on a complex vector space is algebraically equivalent to a topologically irreducible *-representation on a Hilbert space. Topologically irreducible *-representations on a Hilbert space are algebraically isomorphic if and only if they are unitarily equivalent.

This is the Corollary of Theorem 2.9.5 of the Dixmier reference.

If G is a locally compact group, the topology on dual space of the group C*-algebra C*(G) of G is called the Fell topology, named after J. M. G. Fell.

References

- J. Dixmier, C*-Algebras, North-Holland, 1977 (a translation of Les C*-algèbres et leurs représentations)

- J. Dixmier, Les C*-algèbres et leurs représentations, Gauthier-Villars, 1969.

- J. Glimm, Type I C*-algebras, Annals of Mathematics, vol 73, 1961.

- G. Mackey, The Theory of Group Representations, The University of Chicago Press, 1955.

Warning: Default sort key "Spectrum of a C-algebra" overrides earlier default sort key "Nuclear C-algebra". In mathematics — specifically, in measure theory and functional analysis — the cylindrical σ-algebra[1] or product σ-algebra[2][3] is a type of σ-algebra which is often used when studying product measures or probability measures of random variables on Banach spaces.

For a product space, the cylinder σ-algebra is the one that is generated by cylinder sets.

In the context of a Banach space and its dual space of continuous linear functionals the cylindrical σ-algebra is defined to be the coarsest σ-algebra (that is, the one with the fewest measurable sets) such that every continuous linear function on is a measurable function. In general, is not the same as the Borel σ-algebra on which is the coarsest σ-algebra that contains all open subsets of

Definition

Consider two topological vector spaces and with dual pairing , then we can define the so called Borel cylinder sets

for some and . The family of all these sets is denoted as . Then

is called the cylindrical algebra. Equivalently one can also look at the open cylinder sets and get the same algebra.

The cylindrical σ-algebra is the σ-algebra generated by the cylindrical algebra.[4]

Properties

- Let a Hausdorff locally convex space which is also a hereditarily Lindelöf space, then

See also

- Cylinder set – Natural basic set in product spaces

- Cylinder set measure

- Measure theory in topological vector spaces

References

- ↑ Gine, Evarist; Nickl, Richard (2016). Mathematical Foundations of Infinite-Dimensional Statistical Models. Cambridge University Press. p. 16.

- ↑ Athreya, Krishna; Lahiri, Soumendra (2006). Measure Theory and Probability Theory. Springer. pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Cohn, Donald (2013). Measure Theory (Second ed.). Birkhauser. p. 365.

- ↑ Richard M. Dudley, Jacob Feldman und Lucien Le Cam (1971), Princeton University, ed., "On Seminorms and Probabilities, and Abstract Wiener Spaces", Annals of Mathematics 93 (2): 390-392

- ↑ Mitoma, Itaru; Okada, Susumu; Okazaki, Yoshiaki (1977). "Cylindrical σ-algebra and cylindrical measure". Osaka Journal of Mathematics (Osaka University and Osaka Metropolitan University, Departments of Mathematics) 14 (3): 640.

- Ledoux, Michel (1991). Probability in Banach spaces. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. xii+480. ISBN 3-540-52013-9. (See chapter 2)

- Lunardi, Alessandra; Miranda, Michele; Pallara, Diego (2016), Infinite Dimensional Analysis, Lecture Notes, 19th Internet Seminar, Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica Università degli Studi di Ferrara, http://www.dm.unife.it/it/ricerca-dmi/seminari/isem19/lectures/lecture-notes/at_download/file (See chapter 2)

Template:Measure theory Template:Banach spaces

Warning: Default sort key "Cylindrical sigma-algebra" overrides earlier default sort key "Spectrum of a C-algebra".

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics, an ultragraph C*-algebra is a universal C*-algebra generated by partial isometries on a collection of Hilbert spaces constructed from ultragraphs.[1]pp. 6-7. These C*-algebras were created in order to simultaneously generalize the classes of graph C*-algebras and Exel–Laca algebras, giving a unified framework for studying these objects.[1] This is because every graph can be encoded as an ultragraph, and similarly, every infinite graph giving an Exel-Laca algebras can also be encoded as an ultragraph.

Definitions

Ultragraphs

An ultragraph consists of a set of vertices , a set of edges , a source map , and a range map taking values in the power set collection of nonempty subsets of the vertex set. A directed graph is the special case of an ultragraph in which the range of each edge is a singleton, and ultragraphs may be thought of as generalized directed graph in which each edges starts at a single vertex and points to a nonempty subset of vertices.

Example

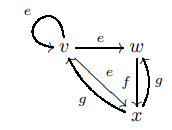

An easy way to visualize an ultragraph is to consider a directed graph with a set of labelled vertices, where each label corresponds to a subset in the image of an element of the range map. For example, given an ultragraph with vertices and edge labels

,

with source an range maps

can be visualized as the image on the right.

Ultragraph algebras

Given an ultragraph , we define to be the smallest subset of containing the singleton sets , containing the range sets , and closed under intersections, unions, and relative complements. A Cuntz–Krieger -family is a collection of projections together with a collection of partial isometries with mutually orthogonal ranges satisfying

- , , for all ,

- for all ,

- whenever is a vertex that emits a finite number of edges, and

- for all .

The ultragraph C*-algebra is the universal C*-algebra generated by a Cuntz–Krieger -family.

Properties

Every graph C*-algebra is seen to be an ultragraph algebra by simply considering the graph as a special case of an ultragraph, and realizing that is the collection of all finite subsets of and for each . Every Exel–Laca algebras is also an ultragraph C*-algebra: If is an infinite square matrix with index set and entries in , one can define an ultragraph by , , , and . It can be shown that is isomorphic to the Exel–Laca algebra .[1]

Ultragraph C*-algebras are useful tools for studying both graph C*-algebras and Exel–Laca algebras. Among other benefits, modeling an Exel–Laca algebra as ultragraph C*-algebra allows one to use the ultragraph as a tool to study the associated C*-algebras, thereby providing the option to use graph-theoretic techniques, rather than matrix techniques, when studying the Exel–Laca algebra. Ultragraph C*-algebras have been used to show that every simple AF-algebra is isomorphic to either a graph C*-algebra or an Exel–Laca algebra.[2] They have also been used to prove that every AF-algebra with no (nonzero) finite-dimensional quotient is isomorphic to an Exel–Laca algebra.[2]

While the classes of graph C*-algebras, Exel–Laca algebras, and ultragraph C*-algebras each contain C*-algebras not isomorphic to any C*-algebra in the other two classes, the three classes have been shown to coincide up to Morita equivalence.[3]

See also

- Leavitt path algebra

- Exel–Laca algebras

- Infinite matrix

- Infinite graph

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 A unified approach to Exel–Laca algebras and C*-algebras associated to graphs, Mark Tomforde, J. Operator Theory 50 (2003), no. 2, 345–368.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Realization of AF-algebras as graph algebras, Exel–Laca algebras, and ultragraph algebras, Takeshi Katsura, Aidan Sims, and Mark Tomforde, J. Funct. Anal. 257 (2009), no. 5, 1589–1620.

- ↑ Graph algebras, Exel–Laca algebras, and ultragraph algebras coincide up to Morita equivalence, Takeshi Katsura, Paul Muhly, Aidan Sims, and Mark Tomforde, J. Reine Angew. Math. 640 (2010), 135–165.

In mathematics, a Lie n-algebra is a generalization of a Lie algebra, a vector space with a bracket, to higher order operations. For example, in the case of a Lie 2-algebra, the Jacobi identity is replaced by an isomorphism called a Jacobiator.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ Baez & Crans 2004, 1. Introduction

- Jim Stasheff and Urs Schreiber, Zoo of Lie n-Algebras.

- A post about the paper at the n-category café.

- Baez, John; Crans, Alissa (2004). "Higher-Dimensional Algebra VI: Lie 2-Algebras". Theory and Applications of Categories 12 (15): 492–528. https://eudml.org/doc/124264.

Further reading

- https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/Lie+2-algebra

- https://golem.ph.utexas.edu/category/2007/08/string_and_chernsimons_lie_3al.html

In mathematics, an AW*-algebra is an algebraic generalization of a W*-algebra. They were introduced by Irving Kaplansky in 1951.[1] As operator algebras, von Neumann algebras, among all C*-algebras, are typically handled using one of two means: they are the dual space of some Banach space, and they are determined to a large extent by their projections. The idea behind AW*-algebras is to forget the former, topological, condition, and use only the latter, algebraic, condition.

Definition

Recall that a projection of a C*-algebra is a self-adjoint idempotent element. A C*-algebra A is an AW*-algebra if for every subset S of A, the left annihilator

is generated as a left ideal by some projection p of A, and similarly the right annihilator is generated as a right ideal by some projection q:

- .

Hence an AW*-algebra is a C*-algebra that is at the same time a Baer *-ring.

The original definition of Kaplansky states that an AW*-algebra is a C*-algebra such that (1) any set of orthogonal projections has a least upper bound, and (2) each maximal commutative C*-subalgebra is generated by its projections. The first condition states that the projections have an interesting structure, while the second condition ensures that there are enough projections for it to be interesting.[1] Note that the second condition is equivalent to the condition that each maximal commutative C*-subalgebra is monotone complete.

Structure theory

Many results concerning von Neumann algebras carry over to AW*-algebras. For example, AW*-algebras can be classified according to the behavior of their projections, and decompose into types.[2] For another example, normal matrices with entries in an AW*-algebra can always be diagonalized.[3] AW*-algebras also always have polar decomposition.[4]

However, there are also ways in which AW*-algebras behave differently from von Neumann algebras.[5] For example, AW*-algebras of type I can exhibit pathological properties,[6] even though Kaplansky already showed that such algebras with trivial center are automatically von Neumann algebras.

The commutative case

A commutative C*-algebra is an AW*-algebra if and only if its spectrum is a Stonean space. Via Stone duality, commutative AW*-algebras therefore correspond to complete Boolean algebras. The projections of a commutative AW*-algebra form a complete Boolean algebra, and conversely, any complete Boolean algebra is isomorphic to the projections of some commutative AW*-algebra.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kaplansky, Irving (1951). "Projections in Banach algebras". Annals of Mathematics 53 (2): 235–249. doi:10.2307/1969540.

- ↑ Berberian, Sterling (1972). Baer *-rings. Springer.

- ↑ Heunen, Chris; Reyes, Manuel L. (2013). "Diagonalizing matrices over AW*-algebras". Journal of Functional Analysis 264 (8): 1873–1898. doi:10.1016/j.jfa.2013.01.022.

- ↑ Ara, Pere (1989). "Left and right projections are equivalent in Rickart C*-algebras". Journal of Algebra 120 (2): 433–448. doi:10.1016/0021-8693(89)90209-3.

- ↑ Wright, J. D. Maitland. "AW*-algebra". Springer. http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php/AW*-algebra.

- ↑ Ozawa, Masanao (1984). "Nonuniqueness of the cardinality attached to homogeneous AW*-algebras". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 93: 681–684. doi:10.2307/2045544.

Warning: Default sort key "AW-algebra" overrides earlier default sort key "Cylindrical sigma-algebra".

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

In mathematics, BF algebras are a class of algebraic structures arising out of a symmetric "Yin Yang" concept for Bipolar Fuzzy logic, the name was introduced by Andrzej Walendziak in 2007. The name covers discrete versions, but a canonical example arises in the BF space [-1,0]x[0,1] of pairs of (false-ness, truth-ness).

Definition

A BF-algebra is a non-empty subset with a constant and a binary operation satisfying the following:

Example

Let be the set of integers and '' be the binary operation 'subtraction'. Then the algebraic structure obeys the following properties:

References

- Walendziak, Andrzej (2007), "On BF-algebras", Math. Slovaca 57 (2): 119–128, doi:10.2478/s12175-007-0003-x

In mathematics, specifically in functional analysis, a C∗-algebra (pronounced "C-star") is a Banach algebra together with an involution satisfying the properties of the adjoint. A particular case is that of a complex algebra A of continuous linear operators on a complex Hilbert space with two additional properties:

- A is a topologically closed set in the norm topology of operators.

- A is closed under the operation of taking adjoints of operators.

Another important class of non-Hilbert C*-algebras includes the algebra of complex-valued continuous functions on X that vanish at infinity, where X is a locally compact Hausdorff space.

C*-algebras were first considered primarily for their use in quantum mechanics to model algebras of physical observables. This line of research began with Werner Heisenberg's matrix mechanics and in a more mathematically developed form with Pascual Jordan around 1933. Subsequently, John von Neumann attempted to establish a general framework for these algebras, which culminated in a series of papers on rings of operators. These papers considered a special class of C*-algebras that are now known as von Neumann algebras.

Around 1943, the work of Israel Gelfand and Mark Naimark yielded an abstract characterisation of C*-algebras making no reference to operators on a Hilbert space.

C*-algebras are now an important tool in the theory of unitary representations of locally compact groups, and are also used in algebraic formulations of quantum mechanics. Another active area of research is the program to obtain classification, or to determine the extent of which classification is possible, for separable simple nuclear C*-algebras.

Abstract characterization

We begin with the abstract characterization of C*-algebras given in the 1943 paper by Gelfand and Naimark.

A C*-algebra, A, is a Banach algebra over the field of complex numbers, together with a map for with the following properties:

- It is an involution, for every x in A:

- For all x, y in A:

- For every complex number and every x in A:

- For all x in A:

Remark. The first four identities say that A is a *-algebra. The last identity is called the C* identity and is equivalent to:

which is sometimes called the B*-identity. For history behind the names C*- and B*-algebras, see the history section below.

The C*-identity is a very strong requirement. For instance, together with the spectral radius formula, it implies that the C*-norm is uniquely determined by the algebraic structure:

A bounded linear map, π : A → B, between C*-algebras A and B is called a *-homomorphism if

- For x and y in A

- For x in A

In the case of C*-algebras, any *-homomorphism π between C*-algebras is contractive, i.e. bounded with norm ≤ 1. Furthermore, an injective *-homomorphism between C*-algebras is isometric. These are consequences of the C*-identity.

A bijective *-homomorphism π is called a C*-isomorphism, in which case A and B are said to be isomorphic.

Some history: B*-algebras and C*-algebras

The term B*-algebra was introduced by C. E. Rickart in 1946 to describe Banach *-algebras that satisfy the condition:

- for all x in the given B*-algebra. (B*-condition)

This condition automatically implies that the *-involution is isometric, that is, . Hence, , and therefore, a B*-algebra is also a C*-algebra. Conversely, the C*-condition implies the B*-condition. This is nontrivial, and can be proved without using the condition .[1] For these reasons, the term B*-algebra is rarely used in current terminology, and has been replaced by the term 'C*-algebra'.

The term C*-algebra was introduced by I. E. Segal in 1947 to describe norm-closed subalgebras of B(H), namely, the space of bounded operators on some Hilbert space H. 'C' stood for 'closed'.[2][3] In his paper Segal defines a C*-algebra as a "uniformly closed, self-adjoint algebra of bounded operators on a Hilbert space".[4]

Structure of C*-algebras

C*-algebras have a large number of properties that are technically convenient. Some of these properties can be established by using the continuous functional calculus or by reduction to commutative C*-algebras. In the latter case, we can use the fact that the structure of these is completely determined by the Gelfand isomorphism.

Self-adjoint elements

Self-adjoint elements are those of the form . The set of elements of a C*-algebra A of the form forms a closed convex cone. This cone is identical to the elements of the form . Elements of this cone are called non-negative (or sometimes positive, even though this terminology conflicts with its use for elements of )

The set of self-adjoint elements of a C*-algebra A naturally has the structure of a partially ordered vector space; the ordering is usually denoted . In this ordering, a self-adjoint element satisfies if and only if the spectrum of is non-negative, if and only if for some . Two self-adjoint elements and of A satisfy if .

This partially ordered subspace allows the definition of a positive linear functional on a C*-algebra, which in turn is used to define the states of a C*-algebra, which in turn can be used to construct the spectrum of a C*-algebra using the GNS construction.

Quotients and approximate identities

Any C*-algebra A has an approximate identity. In fact, there is a directed family {eλ}λ∈I of self-adjoint elements of A such that

- In case A is separable, A has a sequential approximate identity. More generally, A will have a sequential approximate identity if and only if A contains a strictly positive element, i.e. a positive element h such that hAh is dense in A.

Using approximate identities, one can show that the algebraic quotient of a C*-algebra by a closed proper two-sided ideal, with the natural norm, is a C*-algebra.

Similarly, a closed two-sided ideal of a C*-algebra is itself a C*-algebra.

Examples

Finite-dimensional C*-algebras

The algebra M(n, C) of n × n matrices over C becomes a C*-algebra if we consider matrices as operators on the Euclidean space, Cn, and use the operator norm ||·|| on matrices. The involution is given by the conjugate transpose. More generally, one can consider finite direct sums of matrix algebras. In fact, all C*-algebras that are finite dimensional as vector spaces are of this form, up to isomorphism. The self-adjoint requirement means finite-dimensional C*-algebras are semisimple, from which fact one can deduce the following theorem of Artin–Wedderburn type:

Theorem. A finite-dimensional C*-algebra, A, is canonically isomorphic to a finite direct sum

where min A is the set of minimal nonzero self-adjoint central projections of A.

Each C*-algebra, Ae, is isomorphic (in a noncanonical way) to the full matrix algebra M(dim(e), C). The finite family indexed on min A given by {dim(e)}e is called the dimension vector of A. This vector uniquely determines the isomorphism class of a finite-dimensional C*-algebra. In the language of K-theory, this vector is the positive cone of the K0 group of A.

A †-algebra (or, more explicitly, a †-closed algebra) is the name occasionally used in physics[5] for a finite-dimensional C*-algebra. The dagger, †, is used in the name because physicists typically use the symbol to denote a Hermitian adjoint, and are often not worried about the subtleties associated with an infinite number of dimensions. (Mathematicians usually use the asterisk, *, to denote the Hermitian adjoint.) †-algebras feature prominently in quantum mechanics, and especially quantum information science.

An immediate generalization of finite dimensional C*-algebras are the approximately finite dimensional C*-algebras.

C*-algebras of operators

The prototypical example of a C*-algebra is the algebra B(H) of bounded (equivalently continuous) linear operators defined on a complex Hilbert space H; here x* denotes the adjoint operator of the operator x : H → H. In fact, every C*-algebra, A, is *-isomorphic to a norm-closed adjoint closed subalgebra of B(H) for a suitable Hilbert space, H; this is the content of the Gelfand–Naimark theorem.

C*-algebras of compact operators

Let H be a separable infinite-dimensional Hilbert space. The algebra K(H) of compact operators on H is a norm closed subalgebra of B(H). It is also closed under involution; hence it is a C*-algebra.

Concrete C*-algebras of compact operators admit a characterization similar to Wedderburn's theorem for finite dimensional C*-algebras:

Theorem. If A is a C*-subalgebra of K(H), then there exists Hilbert spaces {Hi}i∈I such that

where the (C*-)direct sum consists of elements (Ti) of the Cartesian product Π K(Hi) with ||Ti|| → 0.

Though K(H) does not have an identity element, a sequential approximate identity for K(H) can be developed. To be specific, H is isomorphic to the space of square summable sequences l2; we may assume that H = l2. For each natural number n let Hn be the subspace of sequences of l2 which vanish for indices k ≥ n and let en be the orthogonal projection onto Hn. The sequence {en}n is an approximate identity for K(H).

K(H) is a two-sided closed ideal of B(H). For separable Hilbert spaces, it is the unique ideal. The quotient of B(H) by K(H) is the Calkin algebra.

Commutative C*-algebras

Let X be a locally compact Hausdorff space. The space of complex-valued continuous functions on X that vanish at infinity (defined in the article on local compactness) forms a commutative C*-algebra under pointwise multiplication and addition. The involution is pointwise conjugation. has a multiplicative unit element if and only if is compact. As does any C*-algebra, has an approximate identity. In the case of this is immediate: consider the directed set of compact subsets of , and for each compact let be a function of compact support which is identically 1 on . Such functions exist by the Tietze extension theorem, which applies to locally compact Hausdorff spaces. Any such sequence of functions is an approximate identity.

The Gelfand representation states that every commutative C*-algebra is *-isomorphic to the algebra , where is the space of characters equipped with the weak* topology. Furthermore, if is isomorphic to as C*-algebras, it follows that and are homeomorphic. This characterization is one of the motivations for the noncommutative topology and noncommutative geometry programs.

C*-enveloping algebra

Given a Banach *-algebra A with an approximate identity, there is a unique (up to C*-isomorphism) C*-algebra E(A) and *-morphism π from A into E(A) that is universal, that is, every other continuous *-morphism π ' : A → B factors uniquely through π. The algebra E(A) is called the C*-enveloping algebra of the Banach *-algebra A.

Of particular importance is the C*-algebra of a locally compact group G. This is defined as the enveloping C*-algebra of the group algebra of G. The C*-algebra of G provides context for general harmonic analysis of G in the case G is non-abelian. In particular, the dual of a locally compact group is defined to be the primitive ideal space of the group C*-algebra. See spectrum of a C*-algebra.

Von Neumann algebras

Von Neumann algebras, known as W* algebras before the 1960s, are a special kind of C*-algebra. They are required to be closed in the weak operator topology, which is weaker than the norm topology.

The Sherman–Takeda theorem implies that any C*-algebra has a universal enveloping W*-algebra, such that any homomorphism to a W*-algebra factors through it.

Type for C*-algebras

A C*-algebra A is of type I if and only if for all non-degenerate representations π of A the von Neumann algebra π(A)″ (that is, the bicommutant of π(A)) is a type I von Neumann algebra. In fact it is sufficient to consider only factor representations, i.e. representations π for which π(A)″ is a factor.

A locally compact group is said to be of type I if and only if its group C*-algebra is type I.

However, if a C*-algebra has non-type I representations, then by results of James Glimm it also has representations of type II and type III. Thus for C*-algebras and locally compact groups, it is only meaningful to speak of type I and non type I properties.

C*-algebras and quantum field theory

In quantum mechanics, one typically describes a physical system with a C*-algebra A with unit element; the self-adjoint elements of A (elements x with x* = x) are thought of as the observables, the measurable quantities, of the system. A state of the system is defined as a positive functional on A (a C-linear map φ : A → C with φ(u*u) ≥ 0 for all u ∈ A) such that φ(1) = 1. The expected value of the observable x, if the system is in state φ, is then φ(x).

This C*-algebra approach is used in the Haag–Kastler axiomatization of local quantum field theory, where every open set of Minkowski spacetime is associated with a C*-algebra.

See also

- Banach algebra

- Banach *-algebra

- *-algebra

- Hilbert C*-module

- Operator K-theory

- Operator system, a unital subspace of a C*-algebra that is *-closed.

- Gelfand–Naimark–Segal construction

- Jordan operator algebra

Notes

- ↑ Doran & Belfi 1986, pp. 5–6, Google Books.

- ↑ Doran & Belfi 1986, p. 6, Google Books.

- ↑ Segal 1947

- ↑ Segal 1947, p. 75

- ↑ John A. Holbrook, David W. Kribs, and Raymond Laflamme. "Noiseless Subsystems and the Structure of the Commutant in Quantum Error Correction." Quantum Information Processing. Volume 2, Number 5, pp. 381–419. Oct 2003.

References

- Arveson, W. (1976), An Invitation to C*-Algebra, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90176-0. An excellent introduction to the subject, accessible for those with a knowledge of basic functional analysis.

- Connes, Alain (1994), Non-commutative geometry, Gulf Professional, ISBN 0-12-185860-X, https://archive.org/details/noncommutativege0000conn. This book is widely regarded as a source of new research material, providing much supporting intuition, but it is difficult.

- Dixmier, Jacques (1969), Les C*-algèbres et leurs représentations, Gauthier-Villars, ISBN 0-7204-0762-1, https://archive.org/details/calgebras0000dixm. This is a somewhat dated reference, but is still considered as a high-quality technical exposition. It is available in English from North Holland press.

- Doran, Robert S.; Belfi, Victor A. (1986), Characterizations of C*-algebras: The Gelfand-Naimark Theorems, CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-8247-7569-8.

- Emch, G. (1972), Algebraic Methods in Statistical Mechanics and Quantum Field Theory, Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-23900-3. Mathematically rigorous reference which provides extensive physics background.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "C*-algebra", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=c/c020020

- Sakai, S. (1971), C*-algebras and W*-algebras, Springer, ISBN 3-540-63633-1.

- Segal, Irving (1947), "Irreducible representations of operator algebras", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 53 (2): 73–88, doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1947-08742-5.

Pre-algebra is a common name for a course taught in middle school mathematics in the United States, usually taught in the 6th, 7th, 8th, or 9th grade.[1] The main objective of it is to prepare students for the study of algebra. Usually, Algebra I is taught in the 8th or 9th grade.[2]

As an intermediate stage after arithmetic, pre-algebra helps students pass specific conceptual barriers. Students are introduced to the idea that an equals sign, rather than just being the answer to a question as in basic arithmetic, means that two sides are equivalent and can be manipulated together. They may also learn how numbers, variables, and words can be used in the same ways.[3]

Subjects

Subjects taught in a pre-algebra course may include:

- Review of natural number arithmetic

- Types of numbers such as integers, fractions, decimals and negative numbers

- Ratios and percents

- Factorization of natural numbers

- Properties of operations such as associativity and distributivity

- Simple (integer) roots and powers

- Rules of evaluation of expressions, such as operator precedence and use of parentheses

- Basics of equations, including rules for invariant manipulation of equations

- Understanding of variable manipulation

- Manipulation and plotting in the standard 4-quadrant Cartesian coordinate plane

- Powers in scientific notation (example: 340,000,000 in scientific notation is 3.4 × 108)

- Identifying Probability

- Solving Square roots

- Pythagorean Theorem[4]

Pre-algebra may include subjects from geometry, especially to further the understanding of algebra in applications to area and volume.

Pre-algebra may also include subjects from statistics to identify probability and interpret data.

Proficiency in pre-algebra is an indicator of college success. It can also be taught as a remedial course for college students.[5]

See also

- Precalculus

- Mathematics education in the United States

References

- ↑ In the Introduction to their book on prealgebra.(Szczepanski Kositsky) say that "the math in this book should match what's taught in many middle school classrooms in California, Florida, New York, Texas, and other states." (p. xix)

- ↑ "A Leak in the STEM Pipeline: Taking Algebra Early" (in en). U.S. Department of Education. November 2018. https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/stem/algebra/index.html.