Astronomy:47 Ursae Majoris b

An artist's impression of 47 Ursae Majoris b, depicting it as a Jovian-like planet | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Marcy and Butler et al. |

| Discovery site | |

| Discovery date | 17 January 1996 |

| Doppler spectroscopy | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| astron|astron|helion}} | 2.17 ± 0.05 AU (324.6 ± 7.5 million km) |

| astron|astron|helion}} | 2.03 ± 0.05 AU (303.7 ± 7.5 million km) |

| 2.10 ± 0.02 AU (314.2 ± 3.0 million km)[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.032 ± 0.014[1] |

| Orbital period | 1,078 ± 2[1] d ~2.95 y |

| Average Orbital speed | 21.3 ± 0.3 |

| astron|astron|helion}} | 2,451,917+63−76[1] |

| 334 ± 23[1] | |

| Semi-amplitude | 49.00 ± 0.87[2] |

| Star | 47 Ursae Majoris |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Physics | 200 K |

47 Ursae Majoris b (abbreviated 47 UMa b), formally named Taphao Thong /təˌpaʊ ˈtɒŋ/,[3] is a gas planet and an extrasolar planet approximately 46 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Ursa Major.[4] The planet was discovered located in a long-period orbit around the star 47 Ursae Majoris in January 1996 and as of 2011 it is the innermost of three known planets in its planetary system. It has a mass at least 2.53 times that of Jupiter.

Name

In July 2014 the International Astronomical Union launched NameExoWorlds, a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[5] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[6] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning name was Taphao Thong (Thai: ตะเภาทอง [tā.pʰāw.tʰɔ̄ːŋ]) for this planet.[7] The winning name was submitted by the Thai Astronomical Society of Thailand. Taphaothong was one of two sisters associated with a Thai folk tale.[8]

Discovery

Taphao Thong was discovered by detecting the changes in its star's radial velocity as the planet's gravity pulls the star around. This was achieved by observing the Doppler shift of the spectrum of Chalawan. After the discovery of the first extrasolar planet around a Sun-like star, Dimidium, astronomers Geoffrey Marcy and R. Paul Butler searched through their observational data for signs of extrasolar planets and soon discovered two: Taphao Thong and 70 Virginis b. The discovery of Taphao Thong was announced in 1996.[9]

Orbit and mass

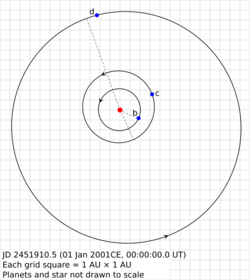

47 Ursae Majoris b orbits at a distance of 2.10 AU from its star, taking 1,078 days or 2.95 years to complete a revolution.[1][4] It was the first long-period planet around a main sequence star to be discovered. Unlike the majority of known long-period extrasolar planets, the eccentricity of the orbit of 47 Ursae Majoris b is low.

A limitation of the radial velocity method used to detect 47 Ursae Majoris b is that only a lower limit on the planet's mass can be obtained. Preliminary astrometric measurements made by the Hipparcos satellite suggest the planet's orbit is inclined at an angle of 63.1° to the plane of the sky, which would imply a true mass 12% greater than the lower limit determined by radial velocity measurements.[10] However, subsequent investigation of the data reduction techniques used suggests that the Hipparcos measurements are not precise enough to adequately characterise the orbits of substellar companions, and the true inclination of the orbit (and hence the true mass) are regarded as unknown.[11]

Physical characteristics

Given the planet's high mass, it is likely that 47 Ursae Majoris b is a gas giant with no solid surface. Because the planet has only been detected indirectly, properties such as its radius, composition and temperature are unknown. Due to its mass it is likely to have a surface gravity 6 to 8 times that of Earth. Assuming a composition similar to that of Jupiter and an environment close to chemical equilibrium, the upper atmosphere of the planet is expected to contain water clouds, as opposed to the ammonia clouds typical of Jupiter.[12]

Although 47 Ursae Majoris b is outside its star's habitable zone, its gravitational influence would disrupt the orbit of planets in the outer part of the habitable zone.[13] In addition, it may have disrupted the formation of terrestrial planets and reduced the delivery of water to any inner planets in the system.[14] Therefore, planets located in the habitable zone of 47 Ursae Majoris are likely to be small and dry.

It has been theorized that light reflections and infrared emissions from 47 UMa b, along with tidal influence, could warm any moons in orbit around it to be habitable, despite the planet being outside the normally accepted habitable zone.[15][16]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Gregory, Philip C.; Fischer, Debra A. (2010). "A Bayesian periodogram finds evidence for three planets in 47 Ursae Majoris". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 403 (2): 731–747. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.16233.x. Bibcode: 2010MNRAS.403..731G.

- ↑ "Planets Table". Catalog of Nearby Exoplanets. http://exoplanets.org/planets.shtml.

- ↑ Thai Astronomical Society, Chalawan, Taphao Thong, Taphao Kaew – First Thai Exoworld Names

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Exoplanet-catalog". https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/exoplanet-catalog/6998/47-ursae-majoris-b/.

- ↑ NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars. IAU.org. 9 July 2014

- ↑ "NameExoWorlds The Process". http://nameexoworlds.iau.org/process.

- ↑ Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015.

- ↑ "NameExoWorlds The Approved Names". http://nameexoworlds.iau.org/names.

- ↑ R. P. Butler et al. (1996). "A Planet Orbiting 47 Ursae Majoris". Astrophysical Journal Letters 464 (2): L153–L156. doi:10.1086/310102. Bibcode: 1996ApJ...464L.153B.

- ↑ I. Han; D. C. Black; G. Gatewood (2001). "Preliminary Astrometric Masses for Proposed Extrasolar Planetary Companions". Astrophysical Journal Letters 548 (1): L57–L60. doi:10.1086/318927. Bibcode: 2001ApJ...548L..57H.

- ↑ D. Pourbaix; F. Arenou (2001). "Screening the Hipparcos-based astrometric orbits of sub-stellar objects". Astronomy and Astrophysics 372 (3): 935–944. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010597. Bibcode: 2001A&A...372..935P.

- ↑ D. Sudarsky et al. (2000). "Albedo and Reflection Spectra of Extrasolar Giant Planets". Astrophysical Journal 538 (2): 885–903. doi:10.1086/309160. Bibcode: 2000ApJ...538..885S.

- ↑ B. Jones et al. (2005). "Prospects for Habitable "Earths" in Known Exoplanetary Systems". Astrophysical Journal 622 (2): 1091–1101. doi:10.1086/428108. Bibcode: 2005ApJ...622.1091J.

- ↑ S. Raymond (2006). "The Search for other Earths: limits on the giant planet orbits that allow habitable terrestrial planets to form". Astrophysical Journal Letters 643 (2): L131–134. doi:10.1086/505596. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...643L.131R.

- ↑ "In Search Of Habitable Moons". Pennsylvania State University. http://www.xs4all.nl/~carlkop/habit.html.

- ↑ "Stellar Data for 47 Ursa Majoris". http://www.exoplaneten.de/47uma/english.html.

External links

- "47 Ursae Majoris". SolStation. http://www.solstation.com/stars2/47uma.htm.

- "47 Ursae Majoris b". Planet Quest. http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov/exoplanet/861.

- "47 Ursae Majoris b". Exoplanet Data Explorer. http://exoplanets.org/detail/47_UMa_b.

Coordinates: ![]() 10h 59m 28.0s, +40° 25′ 49″

10h 59m 28.0s, +40° 25′ 49″

|