Astronomy:Mongolian cosmogony

The Mongol cosmological system is mainly based on the positions, relationships and movements of the sun, the moon, the five major planets in the solar system and the various constellations in the sky. This system of belief is centered around local wild fauna and oral transmission, with few written sources. Mongol cosmology was largely influenced by Chinese civilisation and Buddhism.[1]

Constellations

Generally, stars represent animals turning around the Polar Star which is symbolized by the Altan Gadas (Mongolian: Алтан Гадас, lit. "Golden Spike"). Constellations include Num Sum (Mongolian: Нум сум, lit. "Bow and Arrow") for the Swan, Doloon Burkhan (Mongolian: Долоон бурхан, lit. Seven Gods) for the seven stars of the Big Dipper, Gurvan Maral Od (Mongolian: Гурван марал од, lit. Three Deer Stars) for Orion's Belt, and Hun Tavan Od (Mongolian: Хүн таван од, lit. Five Man Stars) is Cassiopeia.

Planets and stars

Mongolian astrology calculates the positions of each of the planets visible with the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

The names of the celestial and the days they are associated with are:

- the Sun: Nar, Sunday

- the Moon: Sar, Monday

- Mercury: Bud, Wednesday

- Venus: Sugar, Friday

- the Earth: Delkhii

- Mars: Angarag, Tuesday

- Jupiter: Barhasbadi, Thursday

- Saturn: Sanchir, Saturday

- Uranus: Tengeriin van

- Neptune: Dalain van

- Pluto: Delkhiin van.

The noun van at the end of the name of the final three indicates royal status. Therefore a possible translation of Pluto is "the Earth king"; Uranus as "the sky king", and Neptune as "the ocean king." The names of the celestial bodies come from Sanskrit and are largely used in Mongolian, but in an unofficial way.

The star located above Mizar in the Big Bear constellation is prominent in Mongolian astrology. It symbolises the recovery and protection star. According to legend, it was placed there by Tengeriin, the god of heaven, to protect Mizar. In the thirteenth century, to become an archer for Genghis Khan one had to be able to identify these two stars with the naked eye.

Mongolian expertise in astrology and astronomy goes back to the fourteenth and fifteenth century astronomer, mathematician and viceroy in Samarkand, Taraghay, known as Ulug Beg, whose empire spread to Central Asia. Turning away from his royal obligations, he examined celestial bodies and astronomical questions. He was the first to precisely measure Saturn's revolution period (Sanchir) with a sextant of 40 meters radius.

Myths and legends

Mongolians are particularly attached to the Great Bear. This constellation is limited for them to the seven Dipper stars making the bear's tail and body, but the legend concerning it is probably the most famous in Mongolia.

Once upon a time, there were eight orphan brothers gifted with outstanding capabilities living within a kingdom. The king and the queen lived within it peacefully. One day, a monster came and kidnapped the queen. The king asked the eight brothers to bring her back and said: "If one of you succeeds to rescue my beloved, I will give to him a golden arrow". The orphans went together to assist their queen. They searched the monster during two days and three nights, when in the middle of the third night, they found and killed the monster. They brought back the queen in the castle. The king did not cut out the arrow in eight parts, he decided to threw it in the sky. The first to catch it could keep it. The younger brother succeeded the test and changed immediately into the North Star (Polar Star). The seven others changed into the seven gods, the seven Gods visiting their younger brother every night. The name Doloon burkhan (the Seven Gods) come from this legend to appoint the Great Bear and the Golden Stick, Altan Hadaas, the Polar Star.

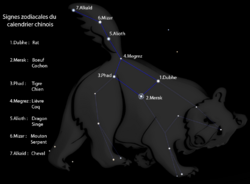

One tradition, based on the birth years in the Chinese calendar, concerns the link between Mongolian people and the Great Bear as one star of this constellation is attributed to each of them. Chinese and Mongolian calendars have some similarities (the Mongolian calendar is a lunar calendar). Each year is symbolized by an animal, itself associated to a star of the constellation Great Bear. The first, Dubhe, corresponds to the Rat's year, the second, Merak, corresponds to the Ox and so on until the end of the Great Bear's tail where Alkaid symbolizes the year of the Horse. Then we come back to the first, the Goat year and we repeat the same way until the twelfth and latest year of the Chinese calendar, the one of the Pig. Therefore, the two stars at the end of the tail are assigned one time only.

Sun

At the origin of the world, there was only one man and vast particularly dry meadows, burned by the seven suns which lit the world. This man, a very good archer, made the promise to the gods that he pierced all these suns without missing a target even once. If he should fail, he would cut himself all the fingers one by one and leave to live in a hole like a marmot (ground-hog) to ward off the curse that would weigh on him. He took his bow, pulled a first arrow and hit his target. A second, a third until the sixth which destroyed the suns. He finished by pulling his seventh arrow towards the last sun, when a swallow flew off and passed through its direction. The bird was hit. The man had not reach his goal, so he left towards exile in a hole, cut his fingers and turned into a marmot. The swallow had just saved our Sun, otherwise all life would have disappeared from the world's surface.

Eclipses

At that time lived a monster named Raah which frightened the entire world. He devoured all who were in its way. The god Orchiwaani owned a magic spring: whoever drank from it became immortal. One day, Raah stole the spring and drunk. The Moon and the Sun caught the monster in the act and reported to Orchiwaani. Seething with rage to hear about this piece of news he went to fight the monster. He cut its head many times but it grew again immediately because Raah had become immortal. He thought then to cut its tail in order to allow all that it ate to leave again directly. Just as Orchiwaani would seize the monster to finish it off, it escaped and disappeared between the Moon and the Sun. Then Orchiwaani asked the Moon, who recaptured Raah and cut its rump and its tail. In revenge, the monster comes back sometimes to eat the Moon or the Sun which exit immediately, giving rise to moon and solar eclipses.[citation needed]

When there is an eclipse, some Mongolians believe it to mean that Raah devours the Moon or the Sun and they make a lot of noise so that the monster liberates the eclipsed star. In the 13th century, Guillaume de Rubruck wrote: "Some [Mongolian people] have knowledge in astronomy and predict them [to other Mongolian people] the Lunar and Solar eclipses and, when it is about to produce one, everybody stocks up on food because they do not pass the door of their habitation. And while the eclipse happened, they play the drum and instruments and do big noise and clamors. When the eclipse is finished, they devote themselves to beverage and festivity and do big party."[2]

Other beliefs linked to the sky

According to a Mongolian legend, a woman devoting herself to count one hundred stars in the sky will dream about her future husband. Sometimes, Mongolians honor the Great Bear (Doloon Burkhan) by throwing milk in its direction. Milk, of white color, symbolizes purity in Mongolia. They pray so that something may be fulfilled, but for several persons, not for just one person, because this would bring bad luck. Milk can be replaced by vodka which, even if it is colorless, symbolizes the dark color and the strength for Mongolians. By doing this, it avoids bad luck, quarrels, fear and fends off evil spirits.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ Masthay, Carl (2006). "A Mongolian Constellation Chart". Mongolian Studies 28: 87–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43193409.

- ↑ Roux, Jean-Paul (1979). Les astres chez les Turcs et les Mongols. Revue de l'histoire des religions. pp. 153–192.

|