Biography:Axel Fredrik Cronstedt

Axel Fredrik Cronstedt | |

|---|---|

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination Axel Fredrik Cronstedt | |

| Born | |

| Died | 19 August 1765 (aged 42) |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Known for | nickel tungsten |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | chemistry Mineralogy |

Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (/kroonstet/ 23 December 1722 – 19 August 1765) was a Swedish mineralogist and chemist who discovered the element nickel in 1751[3][4][5] as a mining expert with the Bureau of Mines.[3] Cronstedt is considered a founder of modern mineralogy,[6] for introducing the blowpipe as a tool for mineralogists, and for proposing that the mineral kingdom be organized on the basis of chemical analysis in his book Försök til mineralogie, eller mineral-rikets upställning (“An attempt at mineralogy or arrangement of the Mineral Kingdom”, 1758).

Life

Axel Fredrik Cronstedt was born on 23 December 1722 on the estate of Ströpsta,[1] in Sudermania.[2] His father, Gabriel Olderman Cronstedt (1670–1757), was a military engineer.[1] His mother, Maria Elizabeth Adlersberg, was Gabriel Cronstedt's second wife.[4]

Beginning in 1738, Axel Cronstedt was an unregistered student at the University of Uppsala, hearing lectures[4] with Johan Gottschalk Wallerius (1709–1785), professor of chemistry, and astronomer Anders Celsius (1701–1744). At Uppsala, he became a friend of Sven Rinman, discoverer of Rinman's green.[1] In 1743, during an unstable period politically, Cronstedt left Uppsala to act as his father's secretary on a military tour of inspection. This tour strengthened his interest in mines and mineralogy.[1]

Cronstedt entered the School of Mines where his instructors included geologist Daniel Tilas (1712-1772). On Tilas' recommendation, Cronstedt went on mining tours in the summers of 1744 and 1745. In 1746, he surveyed copper mines.[4] From 1746 to 1748 Cronstedt took classes with George Brandt, the discoverer of cobalt, at the royal mining laboratory in Stockholm, the Laboratorium Chemicum. There he studied chemical analysis and smelting.[1]

Between 1748, when he completed his studies, and 1758, Cronstedt held a variety of positions.[4] In 1756, he was disappointed to be passed over for a position at the Bureau of Mines, but in 1758, he became a superintendent of mining operations for the mining districts of Öster and Västerbergslagen.[4]

In 1760 Cronstedt married Gertrud Charlotta Söderhielm (1728–1769). In 1761, he moved to the estate of Nisshytte, north of Riddarhyttan. He died there on 19 August 1765.[1][4]

Research

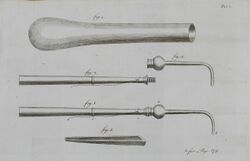

Cronstedt initiated the use of the blowpipe for the analysis of minerals. Originally a goldsmith's tool, it became widely used for the identification of small ore samples, particularly in Sweden where his contemporaries had seen Cronstedt use it. Use of the blowpipe enabled mineralogists to discover eleven new elements, beginning with Cronstedt's discovery of nickel.[1] John Joseph Griffin credits Cronstedt as "the first person of eminence who used the blowpipe" and "the founder of Mineralogy" in A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Blowpipe (1827).[7][8][4]

Cronstedt discovered the mineral now known as scheelite in 1751 at Bispberg Klack, later obtaining samples from the Kuhschacht mine in Freiberg, Germany. He gave it the name tungsten, meaning "heavy stone" in Swedish. Thirty years later, Carl Wilhelm Scheele determined that scheelite was in fact an ore, and that a new metal could be extracted from it. This element then became known by Cronstedt's name, tungsten.[1]

Cronstedt also extracted the element nickel from ores in the cobalt mines of Los, Sweden. The ore was described by miners as kupfernickel because it had a similar appearance to copper (kupfer) and a mischievous sprite (nickel) was supposed by miners to be the cause of their failure to extract copper from it. Cronstedt presented his research on nickel to the Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1751 and 1754. Decades later, some scientists still argued that it was a mixture, and not a new metal, but its nature was eventually accepted.[9][1][10]:690–694[11][12][13]

In 1756, Cronstedt coined the term zeolite after heating the mineral stilbite with a blowpipe flame.[14] He was the first to describe its distinctive properties, having observed the "frothing" when heated with a blowpipe.[15]

Cronstedt's book Försök til mineralogie, eller mineral-rikets upställning (“An attempt at mineralogy or arrangement of the Mineral Kingdom”, 1758) was originally published anonymously. In it, Cronstedt proposed that minerals be classified on the basis of chemical analysis of their composition. He was surprised that others supported his ideas and put them into practice. It was translated into English by Gustav Von Engeström (1738-1813) as An essay towards a system of mineralogy (1770).[1] Engeström added an appendix, "Description and Use of a Mineralogical Pocket Laboratory; and especially the Use of the Blow-pipe in Mineralogy", which brought considerable attention to Cronstedt's use of the blowpipe.[8][16]:127–128[10][17]

Cronstedt noted in Försök til mineralogie, eller mineral-rikets upställning that he had observed an “unidentified earth” in a heavy red stone from the Bastnäs mine in Riddarhyttan. Forty-five years later, Jöns Jacob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger isolated the first element of the lanthanide series of the rare earth elements, cerium, in ore from the mine.[1]

Awards and honors

In 1753, Cronstedt was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Marshall, James L.; Marshall, Virginia R. (2014). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Cronstedt and Nickel". The Hexagon: 12–17. http://www.chem.unt.edu/~jimm/REDISCOVERY%207-09-2018/Hexagon%20Articles/nickel.pdf. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chalmers, Alexander (1813). The General Biographical Dictionary, Vol. 11: Containing an Historical and Critical Account of the Lives and Writings of the Most Eminent Persons in Every Nation. 11. London: Printed for J. Nichols. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9781333069186. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89071082689&view=1up&seq=90. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Gusenius, Edwin M. (1969). "Beginnings of Greatness in Swedish Chemistry (II) Axel Fredrick Cronstedt (1722-1765)". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 72 (4): 476–485. doi:10.2307/3627648. PMID 4918973.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Bartow, Virginia (May 1953). "Axel Fredrick Cronstedt". Journal of Chemical Education 30 (5): 247. doi:10.1021/ed030p247. Bibcode: 1953JChEd..30..247B.

- ↑ Cronstedt, Axel F. (1751). "Rön och försök, Gjorde Med en Malm-art från Los Kobolt Grufvor i Farila Socken och Helsingeland". Kongl. Svenska Veenskapas Academians Handlingar 12: 287–292. https://books.google.com/books?id=K744AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA287.

- ↑ Nordisk familjebok – Cronstedt: "den moderna mineralogiens och geognosiens grundläggare" = "the modern mineralogy's and geognosie's founder"

- ↑ Griffin, John Joseph (1827). A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Blowpipe. Glasgow: R. Griffin & Company. p. 2. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_cqgAAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Abney Salomon, Charlotte A. (5 February 2019). "The Pocket Laboratory: The Blowpipe in Eighteenth-Century Swedish Chemistry". Ambix 66 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/00026980.2019.1573497. PMID 30719948.

- ↑ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education. https://archive.org/details/discoveryoftheel002045mbp.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Enghag, Per (2004), Encyclopedia of the elements, John Wiley and Sons, pp. 236–237, ISBN 978-3-527-30666-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=fUmTX8yKU4gC&pg=PA236

- ↑ Cronstedt, Axel F. (1754). "Fortsättning af rön och försök, Gjorde Med en Malm-art från Los Kobolt Grufvor". Kongl. Svenska Veenskapas Academians Handlingar 15: 38–45. https://books.google.com/books?id=NHdJAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA38.

- ↑ Baldwin, W. H. (1931). "The story of Nickel. I. How "Old Nick's" gnomes were outwitted". Journal of Chemical Education 8 (9): 1749. doi:10.1021/ed008p1749. Bibcode: 1931JChEd...8.1749B.

- ↑ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: III. Some eighteenth-century metals". Journal of Chemical Education 9 (1): 22. doi:10.1021/ed009p22. Bibcode: 1932JChEd...9...22W.

- ↑ Smart, Lesley; Moore, Elaine (2005). Solid state chemistry: an introduction/ (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 302. http://www.uobabylon.edu.iq/eprints/publication_10_10256_250.pdf. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ↑ Colella, Carmine; Gualtieri, Alessandro F. (October 2007). "Cronstedt's zeolite". Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 105 (3): 213–221. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.04.056.

- ↑ Jensen, William B. (December 6, 2012). "The development of blowpipe analysis". The History and Preservation of Chemical Instrumentation: Proceedings of the ACS Divivsion of the History of Chemistry Symposium held in Chicago, Ill., September 9–10, 1985. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 123–150. ISBN 9789400946903. https://books.google.com/books?id=4_X1CAAAQBAJ&pg=PA127.

- ↑ Cronstedt, Axel Fredrik (1770). An essay towards a system of mineralogy / by Axel Fredric Cronstedt ; translated from the original Swedish, with notes, by Gustav von Engestrom ; to which is added, a treatise on the pocket-laboratory, containing an easy method, used by the author, for trying mineral bodies, written by the translator ; the whole revised and corrected, with some additional notes by Emanuel Mendes Da Costa. London: Printed for Edward and Charles Dilly. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100841844.

External links

- Cheetham, A.K.; Peter Day (1992). Solid State Chemistry. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855165-7. https://archive.org/details/solidstatechemis00chee.

|