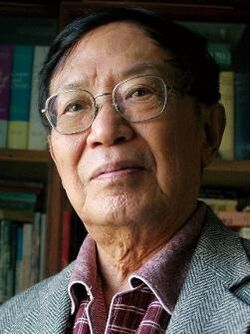

Biography:Li Zehou

Template:Contemporary Chinese political thought Li Zehou (Chinese: 李泽厚; 13 June 1930 – 2 November 2021) was a Chinese scholar of philosophy and intellectual history.[1][2][3] He is considered an influential modern scholar of Chinese history and culture whose work was central to the period known as the Chinese "New Enlightenment" in the 1980s.[1][4][5]

Li served as a long-term vice president of the Chinese Society for Aesthetics (1980–1998).[6] His works on aesthetics, such as The Path of Beauty: A Study of Chinese Aesthetics, triggered an "aesthetics fever (美学热)" in mainland China in the 1980s.[1][7] Soon after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, Li was severely criticized by the Chinese authorities for "poisoning a whole young generation" and his works were forbidden for several years.[8] In 1992, he emigrated to the United States and held visiting or chair professorships at numerous universities, including Colorado College, University of Michigan, University of Wisconsin, Swarthmore College, and University of Colorado Boulder.[1][9][10]

Life

Li was born in Daolin, Ningxiang County, Hunan, on 13 June 1930.[11][12][13] (Another saying: he was born in the city of Hankou, but his family moved to Changsha when he was four years old.[14])

Li was born into a declining gentry family.[15]: 55 His grandfather Li Chaobin (李朝斌) was a general in the Xiang Army under the leadership of Zeng Guofan.[16] His father, an employee of the post office, died of illness in another province. His mother Tao Maolan (陶懋兰) was a teacher in a primary school in his hometown.[17] His elementary school studies occurred at Ningxiang No. 4 High School and his secondary studies at Hunan First Normal University.[18] Li was a Marxist at an early age and participated in covert Communist activities.[15]: 55

After graduating from Peking University in 1954, he joined the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, as a fellow.[13][15]: 55 Between 1956 and 1961, Li participated in the Great Debate of Aesthetics, an academic and ideological campaign.[15]: 55

During the Cultural Revolution, Li was sent to a May Seventh Cadre School.[15]: 55–56

In the late 1970s, Li returned to Beijing and completed a major philosophical treatise, his Critique of Critical Philosophy: a New Approach to Kant.[15]: 56

In 1992, he moved to Boulder, Colorado, United States.[13] In 2021, his head was cryopreserved by the Alcor Life Extension Foundation.[19][20]

Role in Chinese culture

On Li's role in Chinese culture, Yu Ying-shih of Princeton University wrote, "Through (his) books he emancipated a whole generation of young Chinese intellectuals from Communist ideology"[10] Li himself writes that "our younger generation longs to make a contribution to the fields of philosophy and that they are searching [for new avenues] to meet the nation's general goal of modernization as well as the challenge to answer the question about what direction the world is heading."[21]

Critic of Chinese government response to Tiananmen Square

As a result of his criticism of the Chinese government's response to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, he was confined to house arrest for three years. Following substantial U.S. official and academic pressure, the Chinese government granted Li permission to visit the United States in 1991.[8] Subsequently, the U.S. government granted him permanent resident status. From 1992, Li held numerous academic positions, including appointments at Colorado College, the University of Michigan, the University of Wisconsin, Swarthmore College and the University of Colorado Boulder.[22]

Philosophy of the human being

Practical philosophy of subjectivity

With this construct of "Subjectivity", the most fundamental dimension is the technosocial. "Human beings first need to ensure their bodily existence before they can occupy themselves with other matters". But the cultural-psychological aspect, ritual, communal and linguistic dimension separates humans from animals.[23]

Motor thinking

Motor Thinking is the conscious coordination of using a tool. To elaborate, the use of tools is not an instinctive biological activity, but rather one "attained and consolidated through a long period of posteriori learning from experience". The Motor Thinking process creates self-consciousness arising from the attention paid to tool making. Transmission of tool based activities to others, using primitive language, results in semantic thinking: "The forms of motor thinking gradually made way for the forms of language-led thought". Coupled with primitive language, motor thinking ultimately results in the creation of a "vague, common consciousness of being a community" which develops into the "symbolic tools of shamanic rites and ceremonies resulting in the establishment of primitive human society… fundamentally different from that of the animals".[24]

Chinese aesthetics and the relation to freedom

Li's 1981 The Path of Beauty is among his most significant works.[15]: 54–55 Li used the term "emotional-rational structure" to describe what he viewed as the harmony of reason and emotion at the core of Confucian aesthetics.[15]: 57

Li identifies four features that sum up his views on Chinese aesthetics. The concept of Music/Joy (乐: Yue/Le) holds a central place in Chinese culture, "Music is joy". Music has a civilizing effect and "prevents human emotions from developing in an animal-like fashion". Music causes "people to be on good terms with each other, promoting harmony in society". Music is linear, flows in time, and expresses emotion. From this linearity derives the second feature of Chinese aesthetics – the importance of the line in Chinese art. Li recalls that Immanuel Kant also felt was the superior aesthetic visual format. (Chinese art also emphasizes the expression of emotion and pays particular attention to rhythm, rhyme and flavor.) He then goes on to describe the third element which is the blending of feeling and reason: "imaginative reality is more significant than sensible reality." Finally, he lists the "union of heaven and humankind" and describes it as the "fundamental spirit of Chinese philosophy...the relation between human and human, and between humankind and nature." He then proclaims that "to roam with the arts" is essential to the attainment of freedom. Freedom is neither heaven-sent nor given at birth as Rousseau suggested. Freedom is established by humankind ... " For Li, aesthetics are important![25]

Impact on conventional Chinese thought

Li also wrote critiques of contemporary Chinese thought in the second half of the 1980s. Li Zehou’s 1987 essay "The Western is the Substance, and the Chinese is for Application", turned conventional contemporary Chinese thought on its head. Li stated that Western Learning encompasses technology as well as conceptual systems and philosophies including Marxism and is the pluralistic and diverse technosocial basis of modern-day China's reality. Li Zehou concluded that the Chinese application should adapt Western Learning with Chinese traditions, influencing but not dictating the results. To paraphrase, the goal of this examination synthesis should preserve in ethics the strength and splendor of giving precedence to others before oneself; should preserve the value of intuition within the process of reasoning, and should preserve the rich Chinese culture with regard to the handling of inter-human relationships.[26]

In "Dual Variation of Enlightenment and Nationalism", Li Zehou argues that all modern concepts such as freedom, independence human rights, which were discarded after 1919, and all Chinese traditions should be analyzed and investigated. He proposed the idea of "Salvation overwhelmed enlightenment". He wrote that following a relatively long period of peace, developing prosperity and modernization, China would benefit from an examination of the West's "centuries of experience in political-legal theory and practice such as the separations of the three powers". He foresaw that the concept of freedom limited by law would protect the weak and prevent Party officials standing above the law.[27]

Selected works

Li and Liu Zaifu wrote A Farewell to Revolution in 1995.[15]: 46 The book, which criticised Mao-era radicalism and mass uprising as violent and called to "bid farewell to revolution" in favor of incremental reform and the development of democratic temperament, became a major text for those who continued to advocate the New Enlightenment ideals.[15]: 46 The book also led to the increasing divergence of perspective between liberal intellectuals and New Left intellectuals over the New Enlightenment legacy, as New Left intellectuals viewed the book as a veiled neoliberal effort to depoliticise radical thinking and legitimate end-of-history liberal triumphalism.[15]: 47

Other selected works

- History of Chinese Aesthetics (中国美学史), with Liu Gangji, China Social Sciences Press, 1984 (volume 1) and 1987 (volume 2)

- Four Essays on Aesthetics: Toward a Global Perspective, with Jane Cauvel, Lexington Books, 2006

- The Chinese Aesthetic Tradition, with Maija Bell Samei, University of Hawai'i Press, 2010

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ma, Josephine (2021-11-04). "Obituary | Star of 1980s ‘Chinese enlightenment’ dies in the US at 91" (in en). https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3154759/star-1980s-chinese-enlightenment-dies-us-91.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in zh). The Beijing News. 2021-11-03. https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/163591345414728.html. - ↑ Anthony Blencowe Li Zehou, Confucius and Continuity with the Past in Contemporary China . Centre for Asian Studies. University of Adelaide 1993

- ↑ Ames, Roger T., ed (2018). Li Zehou and Confucian Philosophy. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-7289-2. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvvn0qg.

- ↑ "The Transformative Power of Art: LI Zehou's Aesthetic Theory", Jane Cauvel; Philosophy East & West, Vol. 49, 1999

- ↑ "中华美学学会". 2009-07-10. http://philosophy.ac.cn/bsgk/zzjg/stxh/202005/t20200505_5123475.html.

- ↑ Ames, Roger T. (1997). "The Path of Beauty: A Study of Chinese Aesthetics by Li Zehou, Gong Lizeng". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55 (1): 77–79. doi:10.2307/431616. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/27683524.2023.2206304.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rošker, Jana S. (January 2019). "Chapter 1 Li Zehou and His Time". Following His Own Path: Li Zehou and Contemporary Chinese Philosophy. SUNY Press. pp. 9. ISBN 9781438472478. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/163/oa_monograph/chapter/3968053/pdf.

- ↑ Xing, Wen (2023-04-03). "Introduction: "Proper Measure"—In Memoriam of Li Zehou" (in en). Chinese Literature and Thought Today 54 (1-2): 99–101. doi:10.1080/27683524.2023.2206304. ISSN 2768-3524. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/27683524.2023.2206304.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Li Zehou, The Confucian World". http://www.coloradocollege.edu/Academics/Anniversary/Participants/Li.htm.. coloradocollege.edu

- ↑ He Lidan (11 October 2005). (in zh)Xinmin Weekly. http://ent.sina.com.cn/x/2005-10-11/0946861905.html.+"李泽厚,1930年出生,湖南长沙宁乡人。"

- ↑ (in zh)hunan.voc.com.cn. 23 March 2016. http://hunan.voc.com.cn/xhn/article/201603/201603230922311079.html.+"李泽厚,1930年6月出生于湖南宁乡道林。"

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 (in zh)ifeng. 14 August 2014. http://hunan.ifeng.com/hunanspecial/hnzhongguomeng/detail_2014_08/14/2766421_0.shtml.+"李泽厚,中国湖南长沙宁乡人。"

- ↑ Rošker, Jana S. (2019). Following his Own Path: Li Zehou and Contemporary Chinese Philosophy. New York: SUNY. pp. 8. ISBN 978-1-4384-7247-8.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 Tu, Hang (2025). Sentimental Republic: Chinese Intellectuals and the Maoist Past. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674297579.

- ↑ qq.com. 2021-11-03. https://new.qq.com/omn/20211103/20211103A0749U00.html. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ↑ Chen Wangheng (陈望衡) (2021-11-03). Hunan Daily. https://hnrb.voc.com.cn/hnrb_epaper/html/2020-08/14/content_1468220.htm?div=-1. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ↑ Shi Zhenzhuan (石祯专) (2021-11-03). Changsha Evening News. https://www.icswb.com/h/100104/20211103/736067.html.

- ↑ "Leading Chinese Philosopher’s Brain Cryopreserved in the US". Sixth Tone. 2024-02-07. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1014626.

- ↑ "Complete List of Non-Confidential Cryopreserved Alcor Patients". https://www.alcor.org/complete-list-of-non-confidential-cryopreserved-alcor-patients/.

- ↑ From M.E Sharp, Inc., book publishers, "Contemporary Chinese Thought", Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000, Pages: 3 – 19

- ↑ A biographical introduction from a Source Cultures in the 21st Century:Conflicts &Convergences A Symposium Celebrating the 125th Anniversary of The Colorado College 4–6 February 1999

- ↑ "A Supplementary Explanation of Subjectivity" (originally published in 1987), M.E Sharp, Inc., from Summaries of Essays published in "Contemporary Chinese Thought", Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000, Pages 26–31, translated by Peter Wong Yih Jiun

- ↑ An Outline of the Origin of Humankind (Originally published in 1985), M.E Sharp, Inc., Summaries of Essays published in "Contemporary Chinese Thought", Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000 Pages 20 -26 translated by Peter Wong Yih Jiun.

- ↑ "A few Questions Concerning the History of Chinese Aesthetics" (originally published in 1985), M.E Sharp, Inc., Summaries of Essays published in "Contemporary Chinese Thought" Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000, pages 66–78 translated by Peter Wong Yih Jiun.

- ↑ "The Western is the Substance and the Chinese is for Application" (Originally published in 1987), M.E Sharp, Inc., Summaries of Essays published in "Contemporary Chinese Thought" Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000 Pages 32–39,

- ↑ "Dual Variation of Enlightenment and Nationalism" (Originally published in 1987), M.E Sharp, Inc., Summaries of Essays published in "Contemporary Chinese Thought" Volume 31, Number 2 / Winter 1999–2000 Pages 40 to 43

External links

- "Modernization and the Confucian World", Colorado College's 125th Anniversary Symposium on Cultures in the 21st Century: Conflicts and Convergences, address given February 5, 1999

- "Li Zehou And The Marxist Reconstruction Of Confucianism", High Culture Fever, UC Press Ebooks

- Interview with Li (in Chinese), Shanghai Review of Books, October 2010

|