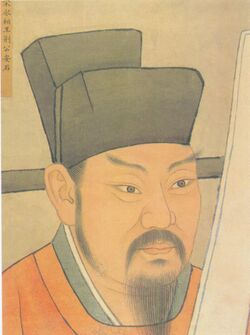

Biography:Wang Anshi

| Wang Anshi |

|---|

Wang Anshi ([wǎŋ ánʂɨ̌]; Chinese: 王安石; December 8, 1021 – May 21, 1086), courtesy name Jiefu (Chinese: 介甫), was a Chinese economist, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. He served as chancellor and attempted major and controversial socioeconomic reforms known as the New Policies.[1][2] These reforms constituted the core concepts of the Song-dynasty Reformists, in contrast to their rivals, the Conservatives, led by the Chancellor Sima Guang.

Wang Anshi's ideas are usually analyzed in terms of the influence the Rites of Zhou or Legalism had on him.[3] His economic reforms included increased currency circulation, breaking up of private monopolies, and early forms of government regulation and social welfare. His military reforms expanded the use of local militias, and his government reforms expanded the education system and attempted to suppress nepotism in government. Although successful for a while, he eventually fell out of favor with the emperor.

Early career

Wang Anshi was born on 8 December 1021, to a family of jinshi degree holders in Linchuan (Fuzhou, Jiangxi province). He placed fourth in the palace exam and obtained a jinshi degree in 1042. He began his career in the Song bureaucracy as a secretary (qianshu) in the office of the assistant military commissioner (jiedu panguan tinggonshi) of Huainan (Yangzhou, Jiangsu province). He was then promoted to district magistrate (zhixian) of Yinxian (Ningbo, Zhejiang province), where he reorganized hydrological projects for irrigation and gave credits to the peasant. Later he was promoted to controller general (tongpan) of Shezhou (Qianshan, Anhui province). In 1060, he was sent to Kaifeng as assistant in the herd office (qunmusi panguan) and then prefect (zhizhou) of Changzhou, commissioner for judificial affairs (tidian xingyu gongshi) in Jiangnan East, assistant in the Financial Commission (sansi duzhi panguan), and finally editor of imperial edicts (zhi zhigao).[4]

Wang's mother died and he observed a mourning period from 1063 to 1066. In 1067, he became governor of Jiangning (Nanjing).[5]

New Policies

Background

During his time in the local administration, Wang Anshi gained an understanding of the difficulties experienced by local officials and the common people. In 1058, he sent a letter ten thousand characters long (Wanyanshu; 万言书/Yanshishu; 言事书/Shang Renzong Huangdi yanshi shu; 上仁宗皇帝言事书) to Emperor Renzong of Song (r. 1022–1063), in which he suggested reforms to the administration in order to solve financial and organizational problems. In the letter he blamed the downfall of previous dynasties on the refusal of their emperors to deviate from traditional patterns of rule. He criticized the imperial examination system for failing to create specialized workers. Wang believed that there should not be generalists but that people should specialize in their roles and not study extraneous teachings.[6] His letter was ignored for ten years until Emperor Shenzong of Song (r. 1067–1085) succeeded the throne. The new emperor faced declining taxes and an increasingly heavy burden of taxation on commoners due to the development of large estates, whose owners managed to evade paying their share of taxes.[7] This led him to seek advice from Wang in 1069. Wang was first appointed vice counsellor (can zhizheng shi; 参知政事), a key position for general administration, and a year later was made chancellor (zaixiang; 宰相).[7]

Objective

The primary objectives of Wang Anshi's New Policies (xinfa) were to cut government expenditure and strengthen the military in the north. To do this, Wang advocated for policies intended to alleviate suffering among the peasantry and to prevent the consolidation of large land estates which would deprive small peasants of their livelihood. He called social elements that came between the people and the government jianbing, translated as "engrossers."[8] By "engrossers" he meant people who monopolized land and wealth and made others their dependents in wealth and agriculture. Wang believed that suppressing jianbing was one of the most important goals.[8] Included in the category of jianbing were owners of large estates, rural usurers, large urban businessmen, and speculators responsible for instability in the urban market. All of them had ties to bureaucrats and had representatives in the government.[9]

Today in every prefecture and subprefecture, there are jianbing [engrossing] families that annually collect interest amounting to several myriad strings of cash without doing anything... What contribution have they made to the state to [warrant] enjoying such a good salary?[10]

— Wang Anshi

According to Wang, "good organization of finance was the duty of the government, and the organization of finance was nothing else than to fulfill public duties."[11] American historian Mary Nourse describes the philosophy of Wang's government that, "The state should take the entire management of commerce, industry, and agriculture into its own hands, with a view to succoring the working classes and preventing them from being ground into the dust by the rich."[12] Wang proposed that "to manage wealth the ruler should see public and private [wealth] as a single whole."[10] Wang believed that it was wealth that united the people and if wealth could not be administered properly, then even the lowliest men who did not possess political power would rise to take advantage of the situation, take control of the economy, monopolize it, and use it to advance their unlimited greed. Under such a situation, Wang considered any claim that the emperor had control of the people to be just words.[13]

Implementation

Wang Anshi was promoted to vice counselor in 1069.[14]

He introduced and promulgated a series of reforms, collectively known as the New Policies/New Laws. The reforms had three main components: 1) state finance and trade, 2) defense and social order, and 3) education and improving of governance.

Equal tax law

The equal tax law (junshuifa), also known as the square field law (fangtianfa) was a land registration project meant to reveal hidden land (untaxed land). Fields were divided into squares 1,000 paces in length on each side. The corners of the fields were marked by earth piles or trees. In the autumn, an official was dispatched to supervise the surveying of the land and to place the soil quality in one of five categories. This information was written in a ledger declared legally binding for the purposes of sale and purchase, and the taxation value assessed appropriately. The law was highly unpopular with land owners, who complained that it restricted their freedom of distribution and other purposes (avoiding tax). Although the square field system was only implemented around the region of Kaifeng, the land surveyed made up 54 percent of known arable land in the Song dynasty. The project was discontinued in 1085. Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100–1125) tried to revive it but the implementation was too impractical and gave up after 1120.[15]

The system of taxation for mining products (kuangshi difen zhi) was a similar project to the equal tax law, except for regulating mining projects.[11]

Green sprouts law

The green sprouts law (qingmiaofa) was a loan to peasants. The government loaned money to buy seeds, or seeds themselves from state granaries, in two disbursements at an interest rate of 2 percent calculated at an average of ten years. Recollections occurred in the summer and winter. Public officials abused the system by forcing loans on the peasants or extracting more than 2 percent interest.[16]

Hydraulic works law

The hydraulic works law (shuilifa) was meant to improve local organization of irrigation works. Instead of using corvée labor, each circuit was supposed to appoint officials to loan money to the people using the local treasury, so that they could hire laborers. The government also encouraged planting mulberry trees to increase silk production.[17]

Labor recruitment law

The labor recruitment law (muyifa) aimed at replacing corvée labor as a form of tax service with hired labor. Each prefecture calculated the funds needed for official projects in advance so that the funds could be distributed appropriately. The government also paid a premium of 20 percent in years of crop failures. Effectively, it transformed labor service to the government into a monetary payment, increasing tax revenue. However, people who were previously exempt from corvée labor were forced to pay taxes for labor on official projects, and thus protested the new law. Although officially abolished in 1086, the new labor recruitment system existed in practice until the end of the Northern Song dynasty in 1127.[18]

Balanced delivery law

The balanced delivery law (junshufa) was meant to curb the prices of commodities purchased by the government and to control the expenditures of the local administration. To do this, circuit level financial institutions in southeast China were made responsible for government purchases and their transport. The central treasury provided funds for the purchase of low cost goods wherever they were available, their storage, and transport to areas where they were expensive. Critics claimed that Wang was waging a price war with merchants.[19]

Market exchange law

The market exchange law (shiyifa), also called the guild avoidance law (mianshangfa), targeted large trading companies and monopolies. A metropolitan market exchange bureau was set up in Kaifeng and 21 market exchange offices in other cities. They were headed by supervisors and office managers who dealt with merchants, merchant guilds, and brokerage houses. These institutions fixed prices for not only resident merchants but also itinerant traders. Surplus commodities were purchased by the government and stored for later sale at a lower price, disrupting price manipulation by merchant monopolies. Merchant guilds that cooperated with the market exchange bureau were allowed to sell goods to the government and buy commodities from government storehouses using money or credit at an interest rate of 10 percent for six months. Small or mid-sized companies and groups of five merchants could provide guarantee with their assets for credit. After 1085, the market exchange bureau and offices became profit making institutions, and bought cheap goods and sold at higher prices. The system stayed in place until the end of the Northern Song dynasty in 1127.[20]

Baojia law

The baojia system, also known as the village defense law or security group law, was a project to improve local security and relieve local government of administrative duties. It ordered groups of ten, fifty, and five hundred men security groups to be organized. Each was to be led by a headman. Initially each household with more than two male adults had to provide one security guard, but this unrealistic expectation was decreased to one per five households later on. The security groups exercised police powers, organized night watches, and trained in martial arts when no agricultural work was required. Essentially it was a local militia with the main effect being a decrease in government expenditures, since the local population was responsible for its own protection.[21]

General and troops law

The general and troops law (jiangbingfa), also known as the creation of commands law (zhijiangfa) targeted improving the relationship between high officials and common troops. The army was divided into commands units of 2,500 to 3,000 men that incorporated a mixed force of infantry, cavalry, archers, as well as tribal troops, instead of each belonging to their own individual unit. This did not include the metropolitan and palace army. The system continued until the end of the Song dynasty.[22]

Three college law

The three college law (sanshefa), also called the Three Hall system, regulated the education of future officials in the Taixue (National University). It divided the Taixue into three colleges. Students first attended the Outer College, then the Inner College, and finally the Superior College. One of the aims of the three-colleges was to provide a more balanced education for students and to de-emphasize Confucian learning. Students were taught in only one of the Confucian classics, depending on the college, as well as arithmetics and medicine. Students of the Outer College who passed a public and institutional examination were allowed to enter the Inner College. At the Inner College there were two exams over a two-year period on which the students were graded. Those who achieved the superior grade on both exams were directly appointed to office equal to that of a metropolitan exam graduate. Those who achieved an excellent grade on one exam but slightly worse on the other could still be considered for promotion, and having a good grade in one exam but mediocre in another still awarded merit equal to that of a provincial exam graduate.[23]

In 1104, the prefectural examinations were abolished in favor of the three-colleges system, which required each prefecture to send an annual quota of students to the Taixue. This drew criticism from some officials who claimed that the new system benefited the rich and young, and was less fair because the relatives of officials could enroll without being examined for their skills. In 1121, the local three-college system was abolished but retained at the national level.[23]

Wang's downfall

The reforms created political factions in the court. Wang Anshi's faction, known as the "Reformers", were opposed by the ministers in the "Conservative" faction led by the historian and Chancellor Sima Guang (1019–1086).[24] As one faction supplanted another in the majority position of the court ministers, it would demote rival officials and exile them to govern remote frontier regions of the empire.[25] One of the prominent victims of the political rivalry, the famous poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101), was jailed and eventually exiled for criticizing Wang's reforms.[25]

Sima and his allies opposed the reforms based on fiscal grounds, but also because they believed that the local elite families rather than the state should be the pillars of society. Fiscally, Wang made it clear that he was not concerned about deficits and promised the emperor that revenues would be adequate even without increasing taxes. Sima did not agree and did not believe that the economy could grow faster than the population.[26] Wang was also in favor of more aggressive foreign policy such as recovering territory and assimilating people to the northwest while Sima preferred a more balanced foreign policy. Sima did not believe that managing wealth was a core function of the government or that it was in their best interests to help those dependent on the rich. He saw that as the breakdown of social order which would cause the eventual downfall of the state. Sima did not even like the imperial examinations and argued that only candidates recommended by court officials should be able to sit the examinations.[27]

Essentially, Sima Guang believed that government was the domain of the pre-existing elite and only the elite. He argued that the empire would be better off if rich families kept more of their wealth. "If (wealth) is in the hands of the state then it is not in the hands of the people," Sima said in a debate with Wang before the emperor. Other officials argued that the baojia system would prevent local gentry from serving in their traditional roles as military commanders, raising private militias and serving as the eyes and ears of the state in the country.[28]

The Green Sprouts program and the baojia system were not conceived as revenue-generating policies but soon were changed to finance new state initiatives and military campaigns. Within a few months of the start of the Green Sprouts program in 1069 the government started to charge an annual interest of 20–30% on the loans it made to farmers. As the officials of the Ever-Normal Granaries who were managing the program were evaluated based on the revenue they could generate, this resulted in forced loans and lack of focus on disaster relief, which was the original task of the Ever-Normal Granaries.[29]

In 1074, a famine in northern China drove many farmers off their lands. Their circumstances were made worse by the debts they had incurred from the seasonal loans granted under Wang's reform initiatives. Local officials insisted on collecting the loans as the farmers were leaving their land. This crisis was depicted as being Wang’s fault. Wang still had the emperor's favor, though he resigned in 1076. With the emperor's death in 1085 and the return of the opposition leader Sima Guang, the New Policies were abolished under the regency of Dowager Empress Xiang.[30] With Sima back in power, he blamed the New Policies' implementation on Shenzong's wish to extend Song borders to match the Han and Tang dynasties, that they were only a tool for irredentism.[31] The pro-New policies faction regained power when Emperor Zhezong came of age in 1093. The policies largely continued under the reign of Emperor Huizong until the end of the Northern Song dynasty in 1126.[31]

Literary

In addition to his political achievements, Wang Anshi was a major poet of his time and he continued to compose poetry throughout his political career.[32] He wrote poems in the shi form, modeled on those of Du Fu.[33] His poetry often included social themes along with the traditional observations of nature.[34] Wang dedicated himself to crafting poetry that was technically sophisticated yet read "smoothly and naturally". While he served at provincial posts and at the central court, his poems were filled with viewpoints, political opinions, and discussion of social and policy issues that were often themes of essays.[35] After he withdrew from central politics and spent his retirement years in Jiangning, His poetry grew increasingly personal and reflective, with his subjects shifting to the landscape and the surroundings of his mountain estate, often adopting a Buddhistic tone.[36]

He was an adherent of the Classical Prose Movement championed by Han Yu and Liu Zongyuan during the Tang dynasty and revived by his older contemporary Ouyang Xiu of the Song dynasty.He was later recognized as one of the Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song.

Legacy

Chinese politicians and historians have continued to look back on the reforms of Wang Anshi as either principled and measured or misguided and disastrous.

The twentieth-century Chinese warlord Yan Xishan cited the reforms of Wang Anshi to justify his use of a limited form of local democracy in Shanxi. Yan believed that the focus and intent of Wang's reforms was to strengthen the Song dynasty by persuading ordinary Chinese to give the dynasty their active support, instead of merely serving it. The system of "democratic" government that Yan justified via the philosophy of Wang Anshi was mostly focused on improving Yan's own popularity without holding any real power, and never became an effective alternative to military dictatorship.[37] On the other hand, the popular scholar Lin Yutang cast Wang as the equivalent of communist totalitarian government in his biography of Wang's adversary Su Dongpo.[38]

See also

- History of the Song dynasty

- Chancellor of China

- Fan Zhongyan

- Sima Guang

References

- ↑ D.B. Boulger (1881). History of China. pp. 388–. https://archive.org/details/historyofchina01bouluoft.

- ↑ Man and the Universe: Japan, Siberia, China. Carmelite House. 1907. pp. 771–. https://books.google.com/books?id=anBKAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA771.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Smith, Paul Jakov (2016-07-19) (in en). State Power in China, 900-1325. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99848-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=9SpADAAAQBAJ&pg=PA237.

- ↑ Mote ch. 6

- ↑ Liu 1959, p. 3.

- ↑ Drechsler 2013, p. 355-356.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Wang Anshi 王安石 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Song/personswanganshi.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bol 1992, p. 250.

- ↑ Zhao 2017, p. 1242.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bol 1992, p. 249.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Reforms of Wang Anshi (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/wanganshireforms.html.

- ↑ Nourse, Mary A. 1944. A Short History of the Chinese, 3rd edition. P.136

- ↑ Zhao 2017, p. 1247.

- ↑ "Wang Anshi | Chinese author and political reformer | Britannica.com". britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/635311/Wang-Anshi.

- ↑ "junshuifa 均税法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/junshuifa.html.

- ↑ "qingmiaofa 青苗法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/qingmiaofa.html.

- ↑ "shuilifa 水利法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/shuilifa.html.

- ↑ "muyifa 募役法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/muyifa.html.

- ↑ "junshufa 均輸法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/junshufa.html.

- ↑ "shiyifa 市易法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/shiyifa.html.

- ↑ "baojia 保甲 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/baojia.html.

- ↑ "zhijiangfa 置將法 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/zhijiangfa.html.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Sanshefa 三舍法 (WWW.chinaknowledge.de)". http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/sanshefa.html.

- ↑ Sivin 1995, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4, https://archive.org/details/eastasiacultural00ebre_0

- ↑ Bol 1992, p. 247.

- ↑ Bol 1992, p. 251-252.

- ↑ Yuhua Wang (2022). The Rise and Fall of Imperial China. Princeton University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-069121517-4.

- ↑ Denis Twitchett and Paul Jakov Smith, ed (2009). The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 414–419. ISBN 9780521812481.

- ↑ Bol 1992, p. 246.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Bol 1992, p. 252.

- ↑ Egan 2010, p. 401.

- ↑ Egan 2010, p. 404.

- ↑ Jaroslav Průšek and Zbigniew Słupski, eds., Dictionary of Oriental Literatures: East Asia (Charles Tuttle, 1978): 192.

- ↑ Egan 2010, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ Egan 2010, pp. 407.

- ↑ Gillin 42

- ↑ Yutang Lin. Gay Genius: The Life and Times of Su Tungpo. New York: John Day, 1947; rpr. Hesperides 2008 ISBN 978-1-4437-2217-9.

Works cited

- Bol, Peter Kees (1992). "This culture of ours" : intellectual transitions in Tʼang and Sung China. Stanford, Calif.. ISBN 978-0-8047-6575-6. OCLC 987792605.

- Chu, Ming-kin (2020), The Politics of Higher Education

- Drechsler, Wolfgang (2013), Wang Anshi and the origins of modern public management in Song Dynasty China

- Egan, Ronald (2010). "The Northern Song (1020–1126)". in Owen, Stephen. The Cambridge history of Chinese literature. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. ISBN 9780521855587.

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 122, 138–142.

- Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. LCCN 66-14308

- von Glahn, Richard (2016), The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century

- Liu, James T.C. (1959), Reform in Sung China

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in ancient China : researches and reflections. Aldershot, Great Britain: Variorum. ISBN 0-86078-492-4. OCLC 32738303. https://books.google.com/books?id=FdDaAAAAMAAJ.

- Zhao, Xuan (2017), Wang Anshi's economic reforms: proto-Keynesian economic policy in Song China

Further reading

- Anderson, Gregory E., To Change China: A Tale of Three Reformers", Asia Pacific: Perspectives, 1:1 (2001).

- Sivin, Nathan, 1995. Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in Ancient China. Researches and Reflections. Variorum Collected Studies Series. Idem.

External links

- Works by Wang Anshi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Preceded by to be added |

Prime Minister of China 1070–1074 |

Succeeded by to be added |

| Preceded by to be added |

Prime Minister of China 1075–1076 |

Succeeded by Sima Guang |

Template:Song dynasty topics Template:Eight Great Literati of Tang and Song Template:Political philosophy

|