Biology:Adamanterpeton

| Adamanterpeton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Family: | †Cochleosauridae |

| Genus: | †Adamanterpeton Milner and Sequeira, 1998 |

| Type species | |

| †Adamanterpeton ohioensis Milner and Sequeira, 1998

| |

Adamanterpeton (from Greek: Αδάμαντας adamantas, meaning 'diamond' and Greek: ἑρπετόν herpetón, meaning 'creeping thing') is a genus of Edopoid Temnospondyl within the family Cochleosauridae. The type species A. ohioensis was named in 1998 and is currently the only known species within this genus.[1] Adamanterpeton is rare in the Linton vertebrate assemblage, with other amphibians like Sauropleura, Ophiderpeton, and Colosteus being more common.[2] Unlike other Linton vertebrates, Adamanterpeton may have been adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle.[1]

History and Discovery

The species is only known from two specimens in the fossil record. The cochleosaurid specimens were discovered in the fossil-rich Allegheny Formation of Linton, Ohio by John Strong Newberry, but were only formally described and figured by Edward Drinker Cope in 1875.[3] Using Cope's (1875) work, Moodie (1916) attributed the specimens to Macrerpeton huxleyi, however, given that the holotype for M. huxleyi was well described and distinct from the two specimens this attribution was not recognized by future authors. In 1930, Alfred Romer categorized the specimens as Anthracosaurus.[4] In 1947, Romer revised his previous classification and designated them as Leptophractus obsoletus. However, instead of using the type specimen of L. obsoletus he used the two cochleosaurid specimens and erroneously classified L. obsoletus as small Temnospondyli belonging to the Edopoidea family.[5][1] In 1963, Romer made revisions to what constituted the Anthracosaurus material from Linton, Ohio, and in doing so removed the two cochleosaurid specimens from its previous classification leaving them with no official systematic status or classification. Hook and Baird (1986) identified them as Gaudrya latistoma,[6] however Sequeira & Milner (1993) disproved this classification.[7]

In their 1998 paper, Sequeira and Milner attempted to classify the cochleosaurid specimens and finding no similarities to existing cochleosaurid genera, considered them to be a plesiomorphic stem cochleosaurid and named the corresponding genus Adamanterpeton and assigned the species name ohioensis to the type specimen.[1]

Paleoenvironment and Geology

The species is only known from the Diamond coal mines of Linton, Ohio. Linton fossils are preserved in a coal deposit known as the Upper Freeport coal, which is a thin deposit of cannel coal that lies beneath a locally thick layer of bituminous coal at the top of the Allegheny Group.[2] The area was likely a meander of a larger river that was cut off, thus forming an oxbow lake. A reduction in sediment deposits to the lake led to an increase in peat-forming mires which allowed for peat to directly accumulate over sapropel found in abandoned channel segments, which is what eventually formed the coal deposits.[2] The considerable depth of the lake was also thought to contribute to the extended length of time that the sapropelic conditions existed for in the area after the lake dried up.

The area is thought to have produced somewhere between 200 and 300 Temnospondyl specimens, of which only two represent A. ohioensis effectively making it the rarest Temnospondyl and one of the rarer tetrapods from the assemblage.[2][6] Milner and Sequeira (1998) attribute its scarcity in the Linton fauna to its terrestrial nature, suggesting it wasn't naturally found in this aquatic environment and was likely an accidental preservation.[1] C. florensis was found in an assemblage in Florence, Nova Scotia that is considered similar to the Linton assemblage in terms of its depositional setting. Both C. florensis and A. ohioensis have relatively corrugated skulls that measure between 100 and 500 mm in length, a feature commonly associated with terrestrial Temnospondyls, which led Milner and Sequeira to hypothesize that the Cochleosaurid family included amphibians and small terrestrial carnivores.[1]

Description

Both specimens only consist of a skull and lack any post cranial materials. The skulls of both specimens aren't fully preserved, however, the type specimen skull measures to be about 130 mm in length and the other specimen measuring around 120 mm.[1]

The honeycomb pattern produced from the pit-and-ridge system, that is characteristic of Temnospondyls, is also observed in Adamanterpeton. However, this ornament pattern is significantly reduced in the area between the anterior snout and the posterior skull table margin, and in the lacrimals and jugals, which is a pattern also observed in C. bohemicus and C. florensis.[8] The specimens also display a pattern where ossified struts extend from either side of the midline of the premaxilla, which then extend to the midline of the nasals and the frontals, and finish along the parietals.[1] The struts are a feature considered to be characteristic of Cochleosaurids.

Similar to Procochleosaurus, Adamanterpeton retains a pineal foramen[9][1] unlike the other members of the Cochleosaurid family, where the pineal foramen is either completely closed or only open in juveniles.[10] It is unknown whether the pineal foramen ever closes in their evolutionary history, however, the size of the foramen in both genera suggest that they do not and instead have the primitive condition found in tetrapods.[8]

The skull roof of the specimens were considered to be representative of the primitive Temnospondyl condition, either through direct observation of the features or through inference, which was necessary as regions of the squamosal and quadratojugal were missing from both specimens.[1]

The palate is also considered to be representative of a primitive Temnospondyl, as it retains primitive features such as smaller interpterygoid vacuities, paired vomers, ectopterygoids and pterygoids. The vomers are elongated, in addition to an elongated prechoanal and interchoanal region, both of which can be associated with elongated choanae, features that are all typical of cochleosaurid as well.[1]

The parasphenoid plate of the cranium is wider than it is long in Adamanterpeton, similar to C. bohemicus[1]. It also contains three shallow depressions on its ventral surface that are thought to maybe be homologous with the parasphenoid tubera that are present in other edopoids.[9]

The mandible was relatively shallow and made up of the same bones typically observed in Temnospondyls, which is a feature also observed in Cochleosaurus and Nigerpeton. This is contrasted with the Procochleosaurus condition where the mandible is deeper and more robust.[11] They had simple, pointed teeth and fangs, that were implanted into the bone with the tooth socket remaining separate.[1][9] Teeth were arranged in the typical Temnospondyl condition with three pairs of fangs on the palatal bones.[1]

Classification

Adamanterpeton is classified as a stem Cochleosaurus, along with Procochleosaurus however, there is uncertainty about whether Adamanterpeton should be more stemward or Procochleosaurus, as despite Adamanterpeton having all the Cochelosaurid character states it lacks the apomorphies shared by more derived cochelosaurids. However, Procochleosaurus data is quite scarce, it is less than 50% complete, so its phylogenetic position remains ambiguous and up to interpretation.[8]

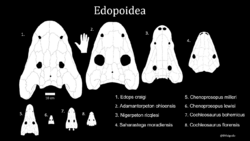

Despite the ambiguity of the order of the stem groups, there has been repeated support for a monophyletic Cochleosauridae family that consists of Procochleosaurus and Adamanterpeton as stem groups to the crown group that consists of Cochleosaurus, Nigerpeton and Chenoprosopus[11][8][1]. The characters that diagnose this family are thought to be pineal foramen closure, anteriorly broad choanae, extreme anterior vomerine elongation, jugal expansion on the palatal surface and are generally agreed upon by researchers,[8] although there has been pushback against the inclusion of pineal foramen.[12]

| Cochleosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Milner, A.R.; Sequeira, S.E.K. (1998). "A cochleosaurid temnospondyl amphibian from the Middle Pennsylvanian of Linton, Ohio, U.S.A.". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 122 (1): 261–290. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb02532.x.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hook, R.W.; Baird, D. (1988). "An overview of the Upper Carboniferous fossil deposit at Linton, Ohio". The Ohio Journal of Science 88 (1): 55–60. https://dspace.lib.ohio-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/23240/V088N1_055.pdf;jsessionid=2B657A45990DBB9CCDC17ECDF54D2F1E?sequence=1.

- ↑ Cope, Edward D. (1875). "Supplement to the Extinct Batrachia and Reptilia of North America". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 15 (2): 261–278. doi:10.2307/1005377. ISSN 0065-9746. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1005377.

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood (1930). The Pennsylvanian tetrapods of Linton, Ohio. American Museum of Natural History.

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood (1947). Review of the Labyrinthodontia. Museum of Comparative Zoology..

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hook, Robert W.; Baird, Donald (1986-06-19). "The Diamond Coal Mine of Linton, Ohio, and its Pennsylvanian-age vertebrates" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 6 (2): 174–190. doi:10.1080/02724634.1986.10011609. ISSN 0272-4634. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.1986.10011609.

- ↑ Sequeira, S. E. K.; Milner, A. R. (1993). "The temnospondyl amphibian Capetus from the upper Carboniferous of the Czech republic.". Palaeontology 36 (3): 657–680.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Sequeira, S. K. (2003). "The skull of Cochleosaurus bohemicus Frič, a temnospondyl from the Czech Republic (Upper Carboniferous) and cochleosaurid interrelationships". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 94 (1): 21. doi:10.1017/S0263593303000026. ISSN 0263-5933. http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0263593303000026.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Damiani, ROss; Sidor, Christian A.; Steyer, J. Sébastien; Smith, Roger M. H.; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Maga, Abdoulaye; Ide, Oumarou (2006-09-11). "The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger. V. The primitive temnospondyl Saharastega moradiensis" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (3): 559–572. doi:10.1080/02724634.2006.10010015. ISSN 0272-4634. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.2006.10010015.

- ↑ Rieppel, O. (1980). "The edopoid amphibian Cochleosaurus from the Middle Pennsylvanian of Nova Scotia.". Palaeontology 23: 143–149.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Steyer, J. Sébastien; Damiani, Ross; Sidor, Christian A.; O'Keefe, F. Robin; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Maga, Abdoulaye; Ide, Oumarou (2006-03-30). "The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger. IV. Nigerpeton ricqlesi (Temnospondyli: Cochleosauridae), and the Edopoid Colonization of Gondwana" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[18:TVFOTU2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0272-4634. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634%282006%2926%5B18%3ATVFOTU%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

- ↑ Hook, R. W. (1993). "Chenoprosopus lewisi, a new cochleosaurid amphibian (Amphibia:Temnospondyli) from the Permo- Carboniferous of north-central Texas. Annals of the Carnegie Museum.". Annals of the Carnegie Museum 62: 273–91. doi:10.5962/p.215123.

Wikidata ☰ Q4680106 entry

|