Biology:Amphidromus

| Amphidromus | |

|---|---|

| |

| The species Amphidromus roseolabiatus has dextral shell coiling. | |

| |

| The species Amphidromus fuscolabris has sinistral shell coiling. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Superfamily: | Helicoidea |

| Family: | Camaenidae |

| Subfamily: | Camaeninae |

| Genus: | Amphidromus Albers, 1850[1] |

| Type species | |

| Amphidromus perversus | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Diversity[2][3] | |

| over 110 species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Amphidromus is a genus of tropical air-breathing land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusks in the family Camaenidae. The shells of Amphidromus are relatively large, from 25 mm (0.98 in) to 75 mm (3.0 in) in maximum dimension, and particularly colorful. During the 18th century, they were among the first Indonesian land snail shells brought to Europe by travelers and explorers. Since then, the genus has been extensively studied: several comprehensive monographs and catalogs were authored by naturalists and zoologists during the time period from the early 19th to the mid 20th centuries. Modern studies have focused on better understanding the evolutionary relationships within the group, as well as solving taxonomic problems.

The genus Amphidromus is unusual in that it includes species that have dextral shell-coiling and species that have sinistral shell-coiling. In addition, some species within this genus are particularly notable because their populations simultaneously include individuals with left-handed and right-handed shell-coiling. This is an extremely rare phenomenon, and very interesting to biologists. Studies focused on the soft anatomy of Amphidromus are scattered and fragmentary. Information on the internal anatomy is known only from a few species, and no larger, comparative morphological study has ever been carried out.

Species in the genus Amphidromus are arboreal — in other words, they are tree snails. However, more detailed information on their habits is still lacking. The general feeding habits of these snails are unknown, but a few species are known to feed on microscopic fungi, lichens or terrestrial algae. Amphidromus themselves are preyed upon by birds, snakes, and probably also by smaller mammals such as rats.

Taxonomy and history

The generic name is derived from the ancient Greek words amphí (ἀμφί), meaning "on both sides", and drómos (δρόμος), meaning "running", alluding to the different chiralities of the shells.[5] The shells of Amphidromus are relatively large, and quite colorful; considerable numbers of them were among the first Indonesian land snail shells brought back to Europe by travelers and explorers during the 18th century. Comparatively speaking, malacologists have gathered a much smaller number of specimens.[4]

Several species and forms were described before 1800, most of them with inadequate locality data. At least two names — Amphidromus laevus (Müller, 1774) and the form A. perversus f. aureus Martyn, 1784 – still (as of 2017) have not yet been reported from a precise locality. During the first half of the nineteenth century, many species and varieties were named, again usually with poor locality data. Not until Eduard von Martens (1867) published his monograph[6] was there an attempt to cover the entire complex of species within this genus. The 1867 monograph contained considerable information both on the variation within the genus, and on the problems of the geographic distribution of the species. Many concepts that originated with von Martens are still (as of 2017) in use.[4]

In 1896, Hugh Fulton[7] organized 142 specific and varietal names into eighteen species groups containing a total of 64 species. When Henry Augustus Pilsbry's 1900 monograph Manual of Conchology[8] appeared, the number of species in the genus Amphidromus had increased to 81, and these were placed in nineteen groups. Pilsbry's study has remained the only illustrated monograph of the genus, and it is still considered indispensable for any serious study of the genus.[4]

Since 1900, the major taxonomic studies on Amphidromus have been faunistic (a study of the fauna of some territory or area) in scope. The papers of American malacologist Paul Bartsch (1917, 1918, 1919)[9][10][11] on the Philippine species, Bernhard Rensch (1932)[12] on the Lesser Sunda Islands forms, and Tera van Benthem Jutting (1950, 1959)[13][14] on Javan and Sumatran populations are especially comprehensive. Potentially the most valuable[4] contribution is that of Curt Haniel (1921),[15] who discussed the variation within A. contrarius and A. reflexilabris on Timor; the variations in color and form were well illustrated in a series of color plates.

Literature published after 1900 contains many scattered descriptions of new color forms and subspecies. Of the 309 names in the nomenclatural list, 111 (35.9%) were published after Pilsbry (1900). Adolf Michael Zilch (1953)[16] listed type specimens in the Senckenberg Museum, and illustrated many previously unfigured species. Frank Fortescue Laidlaw & Alan Solem (1961) recognized 74 species by name, and considered that material from the Banda Islands probably represented an undescribed species. Eleven of the species recognized by Laidlaw & Solem were described after the appearance of Pilsbry's monograph. However, several species recognized by Pilsbry have subsequently been subordinated to subspecific or varietal status, and a few names have been transferred to incertae sedis, since they are based on hundred-year-old references that have not been substantiated by more recent collectors. In fact, the study by Laidlaw & Solem (1961) forms a supplement to Pilsbry's monograph with his extensive plates, and many of Laidlaw & Solem's conclusions concerning the relationships of color forms described as species were taken not so much from new samples, but from the extent of variation that was outlined by Haniel (1921) in his pioneer study.[4]

Characterization

Species in the genus Amphidromus usually have smooth, glossy, brightly colored, elongate or conic, dextrally or sinistrally coiled shells. The shells are moderately large, ranging from 25 mm (0.98 in) to 70 mm (2.8 in) in maximum dimension, having from 6 to 8 convex whorls. Their color pattern is usually monochromatic yellowish or greenish, but can be variegated. The aperture is oblique or ovate in shape, without any teeth or folds, and with the aperture height ranging from two-fifths to one-third of total shell height. The peristome is expanded and/or reflected, and is sometimes thickened. The columella may be straight or recurved, and the parietal callus is weak to well-developed, and the umbilicus may be open or closed. The radula is spatulate, has cusped teeth arranged in rows, usually with a monocuspid central tooth and bicuspid or tricuspid lateral teeth. The jaw is thin and weak, with low flat ribs. The pallial region is sigmurethrous, with a very long, narrow kidney. The genitalia are that of typical camaenids, with a long seminal receptacle, a short penis with low insertion of the retractor muscle, and a short or long epiphallic caecum (flagellum and appendix). The spermatophores have a pentagonal outline in cross-section. Amphidromus are typically arboreal animals.[4][17]

Shell description

The shells of Amphidromus are relatively large, from one to three inches high, and colorful. Amphidromus has an elongate-conic or ovate-conic helicoid shell of 5 to 8 whorls. The shell may be thin and fragile, or very heavy and solid, with no known correlation of shell structure with distribution or habitats.[4]

Shell coiling

In some species within this genus, the shell coils invariably to the right, and in many others just as invariably to the left. However, a significant number of species in this genus are "amphidromine"; this term means that both left- and right-handed shell coiling are found within the same population. One could say they are "polymorphic" for the direction of shell coiling, but because there are only two possible types of shell coiling, they are described as "dimorphic" in coiling. The two types of shell coiling occur in some species in approximately equal numbers, other species have a distinct predominance of one phase. There is as yet no information on the heredity of this character in Amphidromus.[4]

Because almost all other species of amphidromine gastropods, such as ones within the genera Partula and Achatinella, have already become extinct,[18] the genus Amphidromus, containing over 110 species, is uniquely useful for the study of the evolution of asymmetry in animals,[18] and this is why the conservation of this genus is of essential importance to biologists.

-

In A. floresianus, subgenus Syndromus, shell coiling is normally sinistral. Scale bar 10 mm.

-

Shells in the amphidromine species A. perversus can be dextral, as shown here.

-

But shell coiling in A. perversus can also be sinistral, as shown here.

-

Abapertural view of a sinistral shell (left), and apertural view of a dextral shell (right) of A. perversus

Shell shape and sculpture

The whorls of the shell of species of Amphidromus are moderately convex and, with only a few exceptions, are smooth or have a faint sculpture of growth lines. However, a sculpture of moderately heavy oblique radial ribs has appeared at least four separate times in the genus, and can be seen in the following species: Amphidromus costifer Smith from Binh Dinh Province in Vietnam; A. begini Morlet from Cambodia; A. heccarii Tapparone-Canefri from Celebes; and the A. palaceus-A. winteri complex from Java and Sumatra. Correlated with the ribbing is a light, monochrome coloration, and a thin shell with a large aperture and a flaring lip. Many solid shells in other species do show a slight roughening of the surface, but this is very different from the ribbed sculpture mentioned above.[4]

The aperture is generally large, varying from about two-fifths to one-third the height of the shell, often within the same population. Usually the lip is at least somewhat expanded, and in forms such as A. reflexilabris Schepman and A. winteri (Pfeiffer) var. inauris Fulton, the lip can only be called flaring. In A. perversus (Linnaeus) and most other thick-shelled species, the lip is internally thickened, forming a "roll" in its expansion, and has a very heavy parietal callus. In thin-shelled species, the lip is usually a simple reflected edge. The umbilical area can be partially open, nearly closed, or sealed. This feature sometimes provides a useful criterion for specific identification. The angle of the parietal wall varies, but no precise information on this has been compiled.[4]

Generally the whorls of the shell increase rather regularly in size, however, species which are probably closely related, such as A. sinistralis (Reeve) and A. heccarii Tapparone-Canefri, can have quite different degrees of whorl increment. No attempt has been made to express these differences meristically, since most of the available material was inadequate for statistical treatment. Actual dimensions of the shell vary greatly both within and between species. The minimum adult size is about 21 mm high, the observed maximum about 75 mm. There is not much variation in adult size within species: only a few species, notably A. maculiferus, A. sinensis and A. entobaptus, have a variation in adult size that is greater than seven or eight millimeters in total.[4]

Shell coloration

The single most major aspect of shell variation within the genus is the color patterning. In general, many arboreal snails are brightly colored, obvious examples being the bulimulid genera Drymaeus and Liguus, the cepolid Polymita, and the camaenid Papuina. However, Polymita, Liguus and Amphidromus are particularly noted for their color variations. The basic ground color of Amphidromus appears to be yellow, and this color is usually (except for Amphidromus entobaptus) confined to the surface layers of the shell, since worn specimens appear to be nearly devoid of color. In some species the background color is whitish, and a few have dark background colors. The apical whorls are pale, purple, brown, or black, and this sometimes varies within a population (as in A. quadrasi). A few species, for example A. schomburgki, have a deciduous green periostracum.[4]

Continuous zonal patterns can take the form of whitish subsutural bands (A. similis), heavy subperipheral pigmentation (A. perversus var. infraviridis), subsutural color lines (A. columellaris), broad spiral color bands (A. metabletus, A. webbi), or narrow spiral bands (A. laevus). Interrupted zonation can consist of the interruption of bands into spots in (A. maculatus); highly irregular splitting of zones (A. perversus vars. sultanus and interruptus); formation of oblique radial streaks which run parallel to (in A. inversus) or cross (in A. latestrigatus) the incremental growth lines; or almost every conceivable combination and variation of these factors. Often the pattern will change radically from the apex to the body whorl (in A. quadrasi vars.). The aperture, parietal callus, columella, lip, and umbilical region are variously marked with pink, brown, purple, white, or black. Haniel (1921)[15] includes several color plates which clearly demonstrate the extent of color variation within two species of the Syndromus type. A. perversus and A. maculiferus of the subgenus Amphidromus are equally variable, whereas species such as A. inversus and A. similis are almost uniform in coloration.[4]

In shells of most of the species in the subgenus Amphidromus, resting stages are marked by the deposition of a brown or black radial band called a varix. This appears to be rare in the subgenus Syndromus, although the shell of A. laevus does show evidence of interruption of the spiral banding after a resting phase.[4]

Species recognition

Species recognition is based on combinations of minor structural variations in the shape, aperture, whorl contour, umbilical region, and color pattern. It appears to be the case that many species have a stable color pattern, while other species seem to vary tremendously. Adequate unselected field samples will enable a better understanding of the relative stability or variability of particular species in single localities.[4]

Anatomy

Information concerning the soft anatomy of Amphidromus is widely scattered and fragmentary. The most complete account is that of Arnold Jacobi (1895)[19] on specimens from Great Natuna (Natuna Islands) and Djemadja (Anamba Islands). Unfortunately, although it is clear that anatomical differences exist in the two species Jacobi dissected, unfortunately we do not know which forms he worked on, because he had incorrectly identified his material. In his paper he referred to the two species as Amphidromus chloris and the interruptus phase of A. perversus. However, that is not possible, because in reality Amphidromus chloris is a species found only in the Philippine Islands, and the interruptus phase of A. perversus is not present in the Natuna Islands.[4]

Carl Arend Friedrich Wiegmann (1893, 1898)[20][21] discussed portions of the anatomy of A. adamsii, A. porcellanus, A. contrarius, and A. sinistralis. Walter Edward Collinge (1901, 1902)[22][23] briefly noted features of A. palaceus and A. parakensis (reported as A. perversus). Haniel (1921)[15] dissected A. contrarius and A. reflexilabris, and Bernhard Rensch published a few scattered notes in his various faunistic surveys. A few earlier notes are mentioned in Pilsbry (1900).[4][8]

Characters such as the long, narrow kidney with reflexed ureter and closed secondary ureter, the penial complex with distinct penis, which is continuous with the epiphallus, epiphallic caecum (a flagellum and an appendix), unbranched gametolytic duct, lack of vaginal accessory organs, and the basic condition of the nervous and retractor muscle systems support the inclusion of Amphidromus in the family Camaenidae.[17] This group of snails occur in a wide variety of habitats in the tropics of Eastern Asia and Australasia, and is one of the most diverse families in the clade Stylommatophora.[24] Though Laidlaw & Solem (1961) provided no more additional details on the anatomy of Amphidromus, subsequent studies by distinct authors, e.g., Bishop (1977)[25] and Solem (1983),[26] have demonstrated that the reproductive system can provide valuable data for species recognition.[4]

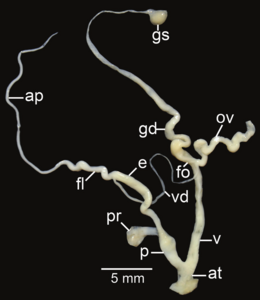

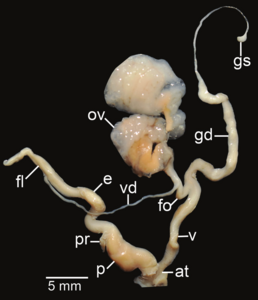

- Reproductive systems isolated through dissection

-

Amphidromus areolatus; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

-

Amphidromus flavus; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

-

Amphidromus fuscolabris; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

-

Amphidromus roseolabiatus; ap – appendix; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

-

Amphidromus syndromoideus; ap – appendix; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

-

Amphidromus xiengensis; at – atrium; e – epiphallus; fl – flagellum; fo – free oviduct; gd – gametolytic duct; gs – gametolytic sac; ov – oviduct; p – penis; pr – penial retractor muscle; v – vagina; vd – vas deferens

Diversity and phylogeny

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of Amphidromus according to Sutcharit et al. (2007)[18] |

Prior to 1900, the similarity in shape of the shell of Amphidromus to that of South American tree snails in the family Bulimulidae had misled taxonomists. However, the dissections made by Wiegmann and Jacobi clearly showed that the inner anatomical features of Amphidromus were the same as those of the Asian-Indonesian Camaenidae, and that the resemblance of the shell of Amphidromus to that of bulimulids was merely an example of parallelism.[4]

- Subgenera and species

Laidlaw and Solem (1961) recognized 75 species in the genus Amphidromus, and placed another seven names under incertae sedis. In 2010, 87 species in the genus Amphidromus were recognized.[18][27][28][4] Species within the genus Amphidromus are divided into two subgenera, as in the following list:[18]

- Subgenus Amphidromus Albers, 1850

Originally described as Helix perversus by Linnaeus in 1758, Amphidromus perversus is the type species of the genus Amphidromus, by the subsequent designation of Eduard von Martens (1860).[29] Species in the subgenus Amphidromus are amphidromine (left-handed and right-handed snails occur within the population) with a few exceptions. Four dextral taxa are: A. givenchyi, A. protania, A. schomburgki dextrochlorus and A. inversus annamiticus; and one sinistral: A. atricallosus classiaris.[18] These species usually have shells which have ht following characteristics: they are large (height often exceeding 35 mm (1.4 in)); they have a height/width ratio of less than 1.85; and a shell color which is yellowish or greenish. Anatomically they have a long epiphallus and flagellum, and an appendix is usually present.[4][17]

- Subgenus Syndromus Pilsbry, 1900[8]

All but two species within the subgenus Syndromus are sinistral. The exceptions are the amphidromine A. glaucolarynx and the dextral A. kruehni.[28] The type species of the subgenus Syndromus is A. contrarius Müller, 1774, by the subsequent designation of Adolf Michael Zilch (1960).[30] Species in the subgenus Syndromus have smaller shells (height usually less than 35 mm (1.4 in) and height/width ratio greater than 1.85), with variable color pattern. They also have a short epiphallus and flagellum, lacking an appendix.[4][17] A third possible subgenus, Goniodromus Bülow, 1905 (type species Amphidromus büllowi Fruhstorfer, 1905),[31] is also cited in the literature, though its subgeneric status is yet to be confirmed.[17]

- Phylogeny

Molecular analyses of partial sequences of 16S rDNA of 18 distinct species carried out by Sutcharit and colleagues (2007)[18] indicate that Amphidromus is a monophyletic group. In their study, different cladograms obtained through distinct methods such as maximum parsimony, neighbor joining and maximum likelihood were congruent among themselves. Though the topology obtained for the subgenus Amphidromus was fairly consistent with current taxonomy, the phylogeny of sinistral Syndromus species showed no such correspondence. Also according to their results, enantiomorphy seems to be the ancestral state of shell coiling in the genus Amphidromus, which is contrary to the general expectation of dextrally coiled shells as an ancestral condition.[18]

Despite being morphologically identical, some specimens supposedly belonging to three species, namely Amphidromus semitessellatus, A. xiengensis and A. areolatus, apparently had polyphyletic origins of mtDNA haplotypes. This resulted in the same species simultaneously appearing in distinct clades along the topology: for instance, A. areolatus can be found in two different clades in Sutcharit and colleague's (2007) cladogram, clustered respectively with A. xiengiensis and also with A. semitesselatus. According to the authors, these results could be explained by convergent and polymorphic shell color patterns (e.g., the shells of the specimens had very similar colors and shape, though the mtDNA markers showed significant differences). Alternatively, they could also be the result of introgressive hybridization or ancestral polymorphism of mtDNA. In any case, analyses of phylogeography using other markers (nuclear markers or other mtDNA markers) or additional morphological characters would still be necessary to further clarify these issues.[18]

Fossil history

Currently, no reliable pre-human fossil occurrences of Amphidromus have been recorded. Tera van Benthem Jutting (1932)[32] reported finding several specimens of A. filozonatus which had been eaten in prehistoric times by natives, in Sampoeng Cave, central Java; and a few years later (van Benthem Jutting, 1937, pp. 92–94)[33] the same author reported a single specimen of A. palaceus from the Trinil Beds of Java. Neither record predates human occupancy, and therefore these shed no light on the pre-human history of Amphidromus.[4]

Ecology

Distribution

The genus Amphidromus ranges from eastern India, in south-western Asia (limited to the north by the Himalayas), to northern Australia (limited eastward by Weber's Line).[17][26] Amphidromus species are found in localities as follows: from the Garo Hills and Khasi Hills of Meghalaya in northeastern India; throughout Burma, Malay Peninsula, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia as far east as the Sulawesi, Banda Islands, Timor and the Tenimber Islands (but not on Ceram, Buru, Halmahera, Batjan Island, the Obi Islands, the Aru and Kei Islands or the Talaud Archipelago and some Celebesian satellite islands); in the southern Philippines , notably Mindanao and the Balabac, Palawan;[4] and in northern Australia (solely represented by Amphidromus cognatus).[26]

Habitat and feeding habits

Amphidromus species are arboreal land snails. Further information concerning the habits and mode of life of the species of Amphidromus is almost non-existent, however, these snails have generally been collected while they were crawling on trees or shrubs. The diet of Amphidromus is unknown, but Amphidromus atricallosus perakensis is thought to feed on microscopic fungi, lichens or terrestrial algae.[4][34]

Life cycle

Despite the great diversity within this genus, as of 2017, comprehensive life-history studies of Amphidromus species are still lacking; only a few observations of behavior of species within the genus exist, and these observations are scattered throughout the literature. A study by Eugen Paravicini (1921)[35] described egg-laying behaviour in Amphidromus palaceus var. pura at Palimanan, West Java. According to Paravicini's observations, in October, 1920, locals from West Java brought in two "nests" containing snails that had just begun depositing their eggs; one snail had folded the exterior leaves of a young bamboo shoot and gummed them together into a pointed cornet. The shoot hung vertically with the narrow end pointed upward, and the wide opening below.[4] The upper part of the sack was filled with eggs when collected. The snail descended slowly, rotating around its longitudinal axis, and deposited eggs until the entire cavity was filled up. If a crack in the basket exposed eggs to the air, they quickly dried up. Two days after capture, egg-laying was finished, and the snail closed the opening by folding over more leaves. Probably four days were spent in egg-laying, since the cavity was half filled at the start of observations. A second nest of similarly folded mango leaves contained 234 eggs. The volume of eggs in each case greatly exceeded the size of the snail, indicating that the eggs must be encapsulated just before deposition. The capsules were very thin, and dried quickly upon any exposure to the air. October marked the start of the rainy season and probably this is the normal breeding period. Eggs of A. porcellanus were reported by van Benthem Jutting (1950, p. 493)[13] to have started hatching only ten days after being laid. Similar nest-building habits have been reported for other species, but no complete study of a life cycle has been published. Up until 1961, no information was available on the cycle of activity, longevity, rate of growth, etc.[4]

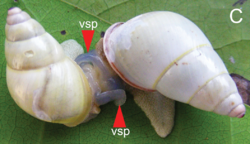

Schilthuizen et al. (2005) described the spatial structure of a population of A. inversus in Malaysia.[36] Schilthuizen et al. (2007) found that there is sexual selection in mating with snails of the opposite chirality.[37] This means that the left-handed snails mate more often with right-handed snails than they do with snails of the same coiling. Additionally there are anatomical adaptations of the spermatophore and of the female part of the reproductive system for the success of these matings.[37]

Predators

Predators of Amphidromus snails include the red-crowned barbet Megalaima rafflesii,[38] and probably other bird species.[34] Asian snakes in the genus Pareas are known to feed on Amphidromus species by removing the soft parts from the shells.[39][17] Many shells of Amphidromus were found in the den of a rat in Malaysia.[37]

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference.[4]

- ↑

Albers J. C. (1850). Die Heliceen nach natürlicher Verwandtschaft: systematisch georduct: 138.

Albers J. C. (1850). Die Heliceen nach natürlicher Verwandtschaft: systematisch georduct: 138.

- ↑ Sutcharit, Chirasak; Ablett, Jonathan; Tongkerd, Piyoros; Naggs, Fred; Panha, Somsak (2015-03-30). "Illustrated type catalogue of Amphidromus Albers, 1850 in the Natural History Museum, London, and descriptions of two new species". ZooKeys (492): 49–105. doi:10.3897/zookeys.492.8641. ISSN 1313-2970. PMID 25878542. PMC 4389215. https://zookeys.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=5002. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Inkhavilay, Khamla; Sutcharit, Chirasak; Panha, Somsak (2017-06-13). "Taxonomic review of the tree snail genus Amphidromus Albers, 1850 (Pulmonata: Camaenidae) in Laos, with the description of two new species". European Journal of Taxonomy (330). doi:10.5852/ejt.2017.330. ISSN 2118-9773.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28

Laidlaw F. F. & Solem A. (1961). "The land snail genus Amphidromus: a synoptic catalogue". Fieldiana Zoology 41(4): 505–720.

Laidlaw F. F. & Solem A. (1961). "The land snail genus Amphidromus: a synoptic catalogue". Fieldiana Zoology 41(4): 505–720.

- ↑ Brown, R. W. (1954). Composition of Scientific Words. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Published by the author. https://archive.org/download/compositionofsci00brow/compositionofsci00brow.pdf.

- ↑

Martens E. von (1867). Die Preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Zoologischer Theil. 2: xii, 447 pp., 22 plates.

Martens E. von (1867). Die Preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien. Zoologischer Theil. 2: xii, 447 pp., 22 plates.

- ↑ Fulton H. (1896). "A list of the species of Amphidromus, Albers, with critical notes and descriptions of some hitherto undescribed species and varieties". Annals and Magazine of Natural History (6)17: 66–94, plates 5–7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2

Pilsbry H. A. (1900). Manual of Conchology, structural and systematic, with illustrations of the species. Second series: Pulmonata. Volume 13. Australasian Bulimulidae: Bothriembryon, Placostylus. Helicidae: Amphidromus. 253 pp., 72 plates, page 184.

Pilsbry H. A. (1900). Manual of Conchology, structural and systematic, with illustrations of the species. Second series: Pulmonata. Volume 13. Australasian Bulimulidae: Bothriembryon, Placostylus. Helicidae: Amphidromus. 253 pp., 72 plates, page 184.

- ↑ 15px Bartsch P. (1917). "The Philippine land snails of the genus Amphidromus". U. S. Nat. Mus. Bull. 100(1), part 1: 1–47, 22 plates.

- ↑ 15px Bartsch P. (1918). "The land snails of the genus Amphidromus from the islands of the Palawan Passage". Jour. Washington Acad. Sci. 8(11): 361–367.

- ↑ 15px Bartsch P. (1919). "Critical remarks on Philippine Island land shells". Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington 32: 177–184.

- ↑ (in German) Rensch B. (1932). "Die Mollusken Fauna der Kleinen Sunda-Inseln, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores und Sumba". Zool. Jahrb., Syst. 63: 1–130, 3 plates.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 van Benthem Jutting T. (1950). "Critical studies of the Javanese pulmonate land-shells of the families Helicarionidae, Pleurodontidae, Fruticicolidae and Streptaxidae". Treubia 20(3): 381–505, 107 figs.

- ↑ van Benthem Jutting T. (1959). "Catalogue of the non-marine Mollusca of Sumatra and of its satellite islands". Beaufortia 7(83): 41–191, 1 plate, 11 figs.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 (in German) Haniel C. (1921). "Variationsstudie an Timoresischen Amphidromus Arten". Zeits. Induct. Abstamm. und Vererbungsl. 25(1–2): 88 pp., 5 plates.

- ↑ (in German) Zilch A. M. (1953). "Die Typen und Typoide des Natur-Museums Senckenberg. 10: Mollusca, Pleurodontidae (1)". Archiv für Molluskenkunde 82(4–6): 131–140, plates 22–25.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Sutcharit, C. (2005). "Taxonomic review of the tree snail Amphidromus Albers, 1850 (Pulmonata: Camaenidae) in Thailand and adjacent areas: subgenus Amphidromus". Journal of Molluscan Studies 72: 1–30. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyi044.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 Sutcharit, C.; Asami, T.; Panha, S. (2007). "Evolution of whole-body enantiomorphy in the tree snail genus Amphidromus". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 20 (2): 661–672. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01246.x. PMID 17305832.

- ↑ (in German) Jacobi A. (1895). "Anatomische Untersuchungen an Malayischen Landschnecken". Arch. Naturg. 61: 293–318, plate 14.

- ↑ 15px (in German) Wiegmann C. A. F. (1863). "Beitrage zur Anatomie der Landschnecken des Indischen Archipels". In: Weber (1863). Zool. Ergeb. Reisen Indischen Arch. 3: 112–259, plates 9–16.

- ↑ 15px (in German) Wiegmann C. A. F. (1898). "Landmollusken (Stylommatophoren)". Zootomischer Teil. Abhl. Sencken. Naturf. Gesell. 24(3): 289–557, plates 21–31. 514-527.

- ↑ Collinge W. E. (1901). "Note on the anatomy of Amphidromus palaceus, Mouss". Jour. Malac. 8(2): 50–52, plate 4.

- ↑ Collinge W. E. (1902). "On the non-operculated land and fresh-water molluscs collected by members of the "Skeat Expedition" in the Malay Peninsula, 1899–1900". Op. cit. 9(3): 71–95, plates 4–6.

- ↑ Cuezzo, M.G. (2003). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Camaenidae (Mollusca: Stylommatophora) with special emphasis on the American taxa". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 138 (4): 449–476. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2003.00061.x.

- ↑ Bishop, M.J. (1977). "Anatomical notes on some Javanese Amphidromus (Pulmonata: Camaenidae)". Journal of Conchology 29: 199–205.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Solem, A (1983). "First record of Amphidromus from Australia with anatomical note on several species (Mollusca: Pulmonata: Camaenidae)". Records of the Australian Museum 35 (4): 153–166. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.35.1983.315.

- ↑ Chan S.-Y., Tan S.-K. & Abbas J. B. (2008). "On a new species of Amphidromus (Syndromus) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Camaenidae) from Rotti Island, Indonesia". Occasional Molluscan Papers 1: 1–5. PDF , Internet Archive

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Chan S.-Y. & Tan S.-K. (2008). "On a new species of Amphidromus (Syndromus) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Camaenidae) from Sumba Island, Indonesia". Occasional Molluscan Papers 1: 6–10. PDF , Internet Archive

- ↑ von Martens E. (1860). Die Heliceen 2nd ed., p. 184.

- ↑ Zilch A. M. (1960). Gastropoda, Euthyneura. Handb. Palaozool. (6)2(4): 601–834, figs. 2112–2515. page 623.

- ↑ Bülow (1905). Nachr. d. Malak. Gesell. 37: 83.

- ↑ van Benthem Jutting T. (1932). "On prehistoric shells from Sampoeng Cave (central Java)". Treubia 14(1): 103–108, 5 figs.

- ↑ van Benthem Jutting T. (1937). "Non-marine Mollusca from fossil horizons in Java with special reference to the Trinil fauna. Zool. Meded., 20: 83–180, pis. 4–12.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Lok A. F. S. L. & Tan S. K. (2008). "A review of the Singapore status of the green tree snail, Amphidromus atricallosus perakensis Fulton, 1901 and its biology". Nature in Singapore 1: 225–230. PDF

- ↑ Paravicini E. (1921). "Die Eiablage zweier Javanischer Landschnecken". Archiv für Molluskenkunde 53: 113–116, plate 2.

- ↑ Schilthuizen, M; Scott, B J; Cabanban, A S; Craze, P G (2005). "Population structure and coil dimorphism in a tropical land snail". Heredity 95 (3): 216–220. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800715. PMID 16077741.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Schilthuizen, M.; Craze, P. G.; Cabanban, A. S.; Davison, A.; Stone, J.; Gittenberger, E.; Scott, B. J. (2007). "Sexual selection maintains whole-body chiral dimorphism in snails". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 20 (5): 1941–1949. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01370.x. PMID 17714311.

- ↑ Wee J. (2006). "Red-crowned barbet feeding on snail". http://besgroup.talfrynature.com/2006/06/01/red-crowned-barbet-feeding-on-a-snail/ . Accessed 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Danaisawadi, P.; Asami, T.; Ota, H.; Sutcharit, C.; Panha, Somsak (5 April 2016). "A snail-eating snake recognizes prey handedness". Scientific Reports 6 (1): 23832. doi:10.1038/srep23832. PMID 27046345. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...623832D.

Further reading

- Craze, Paul G.; Bin Elahan, Berjaya; Schilthuizen, Menno (2006). "Opposite shell-coiling morphs of the tropical land snail Amphidromus martensi show no spatial-scale effects". Ecography 29 (4): 477–486. doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04731.x. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/2148/1/Craze%2C_bin_Elahan_%26_Schilthuizen_2006.pdf.

- Dharma, E. (2008). "Penerapan sistem pakar dalam perancangan program identifikasi jenis siput-pohon Amphidromus di Indonesia. Part 1". Berita Solaris 11 (2): 12–16.

- Dumrongrojwattana P., Mutchacheep S. & Senapin R. (2006). "Identification of 7 Thai arboreal snails genus Amphidromus Alber, 1850 by using morphometrics technique (Pulmonata: Camaenidae)". The Proceeding of 44th Kasetsart University Annual Conference, 30 Jan – 2 Feb 2006, Subject Science: 7 pp. Kasetsart University, Bangkok.

- Goldberg, R. L.; Severns, M. (1997). "Isolation and evolution of the Amphidromus in Nusa Tenggara". American Conchologist 25 (2): 3–7. http://www.conchologistsofamerica.org/articles/y1997/9706_Gold&Seve.asp. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Panha, S.; Sutcharit, C.; Tongkerd, P.; Burch, J. B. (2001). "Morphogeography of an endemic tree snail genus Amphidromus of Thailand (Pulmonata: Camaenidae)". Of Sea and Shore 24 (2): 106–113.

- Prasankok, P; Ota, H; Toda, M; Panha, S (2007). "Allozyme variation in the camaenid tree snails Amphidromus atricallosus (Gould, 1843) and A. inversus (Müller, 1774).". Zoological Science 24 (2): 189–97. doi:10.2108/zsj.24.189. PMID 17409732.

- Severns, M. (2003). "A quick explanation of Amphidromus". Of Sea and Shore 25 (4): 228–231.

- Severns, M. (2006). "A new species and a new subspecies of Amphidromus from Atauro Island, East Timor (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Camaenidae)". Basteria 70: 23–28.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q3977888 entry

|