Biology:Archeopelta

| Archeopelta | |

|---|---|

| |

| A vertebra and adjacent osteoderms from CPEZ-239a | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Archosauria/Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Clade: | Suchia |

| Family: | †Erpetosuchidae |

| Genus: | †Archeopelta Desojo et al., 2011 |

| Type species | |

| †Archeopelta arborensis Desojo et al., 2011

| |

Archeopelta is an extinct genus of carnivorous archosaur from the late Middle or early Late Triassic period (late Ladinian to early Carnian stage). It was a 2 m (6 ft) long predator which lived in what is now southern Brazil.[1] Its exact phylogenetic placement within Archosauriformes is uncertain; it was originally classified as a doswelliid, but subsequently it was argued to be an erpetosuchid archosaur.[2]

Discovery

It is only known from the holotype CPEZ-239a, which consists of partial skeleton (including vertebrae, partial right front and hind limbs, a partial hip, and an undetermined bone which may be part of a tibia) and braincase. It was found in the Santa Maria 1 Sequence, previously known as the Santa Maria Formation, in Chiniquá region, São Pedro do Sul of Rio Grande do Sul State. It was first named by Julia B. Desojo, Martín D. Ezcurra and César L. Schultz in 2011 and the type species is Archeopelta arborensis. The generic name comes from archaios, ancient in Greek and pelta, shield, in reference to its thick osteoderms. The specific name is derived from arbor, tree in Latin, in reference to Sanga da Árvore where the fossils were found.[3]

Description

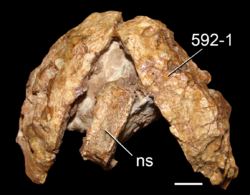

CPEZ-239a's braincase is low, without an occipital neck. The exoccipitals do not meet each other medially. The paraoccipital processes extend outwards and slightly downwards, and the supraoccipital has a ridge. Uniquely, a very deep fossa is present in the corner of the opisthotics. The exit of the hypoglossal nerve is a single opening. The basal tubera are very low and separated by a deep notch. The parabasisphenoid is short and its exits for the internal carotid arteries are small and pushed to the rear edge of the bone. The basipterygoid processes are close to each other and project anterolaterally. The exit for the facial nerve is present on the vestibule, and the lamina separating the metotic foramen and the fenestra ovalis is very thin.

The back vertebrae are only slightly elongated and are not constricted from the sides. The diapophyses are thick, subrectangular, and elongated. The prezygapophyses are short while the neural spines are long and oval-shaped in cross section. The first 'primordial' sacral vertebra (likely the second sacral) is low and wide, with characteristically-shaped sacral ribs. The sacral ribs expand anteroposteriorly at their tips, with the anterior expansions being large and subtriangular. The first primordial's unique prezygapophyses are very large and circular, with their faces pointing upward and inwards. On the other hand, the postzygapophyses are short, downwards-pointing, and connected by a V-shaped hyposphene. Although incomplete, the second 'primordial' sacral (likely the third sacral) is also low, with sacral ribs similarly shaped to those of the first 'primordial' sacral.[3]

The humeral head is offset from the humeral shaft, and the right humerus as a whole is wide and distally tapering (although missing the distal portion). A thin bone has been interpreted to be a right ilium, with an unusual illiac blade which is S-shaped in posterior view. However, this interpretation is uncertain and the bone's shape may be a result of postmortem deformation.[2] The right ischium has a long and deep pubic peduncle but a very short illiac peduncle. The ischial shaft is thin and the lower edge bends towards the midline. The right femur is S-shaped from the front, with a transversely very wide distal end and poorly developed condyles and tubercules. The right tibia is anteroposteriorly wide but distally tapering and missing its distal tip. An unusual rod-like bone may be the distal part of a tibia.[3]

Several osteoderms are preserved with CPEZ-239a. At least two rows of osteoderms attached to each neural spine of the vertebrae, and there is evidence that additional rows of lateral osteoderms were also present. The osteoderms are very thick and quadrangular in shape, with straight posterior and medial borders and rounded anterior and lateral borders. They were rough and covered in deep, circular pits, with each possessing an anterior articular lamina (a smooth area where the preceding osteoderm would have overlapped the front edge of the following osteoderm). Although they had serrated edges, they did not possess a raised keel or peak (a dorsal prominence) on their surface. Small, circular plates attached to the femur may be appendicular osteoderms, although poor preservation makes this uncertain.[2]

Classification

Upon the initial description of Archeopelta, it was placed as a close relative of Doswellia in the newly created family Doswellidae. This referral was due to the structure of its osteoderms, which were very similar to those of Doswellia. In addition, Archeopelta shared several other features with Doswellia which were unknown in Tarjadia, which was rather incomplete at the time of Archeopelta's description. Among these features are the wide first primordial sacral, a long and laterally deflected illiac blade, and anterolaterally-projected basipterygoid processes. This is the cladogram from the study, after Desojo, Ezcurra & Schultz, 2011:[3]

| Archosauromorpha |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2013, Lucas, Spielmann, and Hunt claimed that Archeopelta was a junior synonym of Tarjadia due to a lack of distinguishing features between the two.[4] However, Ezcurra (2016) provided several differences between the two genera. For example, Archeopelta has unconstricted dorsal vertebrae and a ridge on the supraoccipital, while Tarjadia has the opposite traits. Nevertheless, Ezcurra observed that both genera had very thick osteoderms, and he considered that both of them were doswellids more closely related to each other than to Doswellia.[5]

New specimens of Tarjadia described in 2017 provided a phylogenetic analysis that argued that Tarjadia and Archeopelta were not doswellids, but rather pseudosuchian archosaurs of the family Erpetosuchidae. The strict consensus tree of this analysis is given below. Erpetosuchid osteoderms are similar to Doswellid osteoderms, which explains the earlier classification of Tarjadia and Archeopelta. Even in non-parmonious phylogenetic trees of the analysis which forced them to be recovered as doswellids, Tarjadia and Archeopelta still formed a clade with Erpetosuchus. Despite the change in Archeopelta's classification, it still forms a clade with Tarjadia as an erpetosuchid. This is due to both of them possessing a very short or absent occipital neck and osteoderms without a dorsal prominence.[2]

| Eucrocopoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Sues, Hans-Dieter; Desojo, Julia B.; Ezcurra, Martín D. (2013-01-01). "Doswelliidae: a clade of unusual armoured archosauriforms from the Middle and Late Triassic" (in en). Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1144/SP379.13. ISSN 0305-8719. Bibcode: 2013GSLSP.379...49S. https://www.academia.edu/20415098.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Martín D. Ezcurra; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Agustín G. Martinelli; Sebastián Rocher; M. Belén von Baczko; Miguel Ezpeleta; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; E. Martín Hechenleitner et al. (2017). "Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea". Nature Ecology & Evolution 1 (10): 1477–1483. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0305-5. PMID 29185518. Bibcode: 2017NatEE...1.1477E. https://www.academia.edu/34560615.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Julia B. Desojo, Martin D. Ezcurra and Cesar L. Schultz (2011). "An unusual new archosauriform from the Middle–Late Triassic of southern Brazil and the monophyly of Doswelliidae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 161 (4): 839–871. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00655.x.

- ↑ Lucas, S.G.; Spielmann, J.A.; Hunt, A.P. (2013). "A new doswelliid archosauromorph from the Upper Triassic of West Texas". in Tanner, L.H.. The Triassic System. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 61. pp. 382–388. http://paleo.cortland.edu/globaltriassic2/Bulletin%2061%20Final/31-Lucas%20et%20al%20(Ankylosuchus).pdf. Retrieved 2017-12-23.

- ↑ Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms" (in en). PeerJ 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMID 27162705.

Wikidata ☰ Q2908660 entry

|