Biology:Austrolestes colensonis

| Austrolestes colensonis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Suborder: | Zygoptera |

| Family: | Lestidae |

| Genus: | Austrolestes |

| Species: | A. colensonis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Austrolestes colensonis (White, 1846)[1]

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

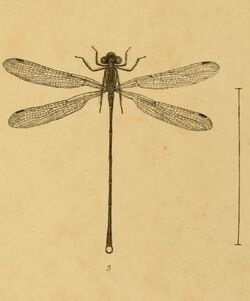

Austrolestes colensonis (Māori: kekewai),[3] commonly known as the blue damselfly, is a species of damselfly of the family Lestidae. It is endemic to New Zealand and can commonly be found throughout the country, and at any time of the year. It is New Zealand's largest damselfly, and only blue odonate.[3]

Taxonomy

This species was first being described by Adam White in 1846.[1][4] The first reference to this species was an illustration published under the name Agrion colensonis.[2] In 1862 Edmond de Sélys Longchamps wrote a description of the species and used the name Lestes colensonis.[5] The New Zealand entomologist George Hudson described, discussed and illustrated this species in 1904 under the name L. colensonis.[6] In 1913 Robin Tillyard placed this species within the genus Austrolestes.[7]

Description

Hudson described the species as follows:

The expansion of the wings is 2 1⁄8 inches, and the length of the body 1 3⁄4 inches. The general colour of the male is dark purplish-black, with brilliant blue markings. The front of the labium, the pronotum, two broad stripes on the mesonotum, the articulations of the wings and the articulations of the abdomen are brilliant blue. The legs are black above and yellowish-brown beneath. The superior appendages of the male are like pincers toothed inside and having a tubercle at the base inside, which is the commencement of a dilatation, terminated towards the middle by a very sharp tooth ; the end inclined downwards and curved slightly outwards. The inferior appendages are not half the length of the superior ; they are brown, thick, approximated, and slightly attenuated. In the female the head and pronotum are dull slaty black, the central portions of the mesonotum brilliant green-edged, first with a narrow band of white and then broadly with black. The abdomen is bright green at the base, becoming dull purple towards the tip ; the end of each segment is marked with a shaded ring of black, and the beginning of the succeeding segment with a sharp, fine ring of white. The anal appendages are separated, sub-cylindrical, yellowish, shorter than the last segment, the valves slightly toothed at the tips.[6]

A. colensonis is the largest damselfly in New Zealand.[8][3] Adult males can be distinguished by their widely separated blue eyes alongside a pale blue upper border on the mouthparts.[8] The thorax has three metallic blue stripes separated by black, which is the predominant colour.[8] Along the abdomen each segment from two to seven has a blue anterior ring located on the margin between segments; the remainder of the abdomen is black except for a dorsal blue area on segment ten.[8] Females are similar to the male but with a thicker abdomen which has long thin appendages at the clubbed tip. Both females and young males are iridescent green in colour rather than blue.[9]

The larvae of this species are between 17 and 21 millimetres in length and have a broad head with large eyes, a cylindrical body shape and a rounded tip on the tail gill with no hairs, and three horizontal brown stripes.[8][10]

Distribution

This species is found throughout New Zealand, including Stewart Island and Chatham Island; the Chatham Island individuals seem to be genetically distinct from the mainland population, and most have an interrupted blue stripe on the thorax, but currently this is thought insufficient to consider them a separate species.[9] A. colensonis can be seen near water at any time, but especially November to April; adults seen in June and July may be overwintering.[9] It is the main damselfly species in mountain tarns, so is presumably cold-tolerant.[9]

Life cycle

A. colensonis has a twenty-year life cycle.[11] Some eggs hatch in the summer that they are laid while others overwinter and hatch the following spring. Those eggs that hatch in the following year overwinter in a dormant state.[11] Temperature is the major influence that regulates the rate of development. Too low and it can cause the death of the embryo.[11]

Eggs can hatch in about 20–21 days where the temperature is 20 degrees Celsius.[8] Nymphs then live for a year to a year and a half before metamorphosis takes place.[12] Before emergence, the nymphal darkens until it is nearly black in colour. The nymphs may take several short trips from the water a few days before emergence.[8] Emergence normally takes place on rush or grass stalks 10–40 cm above the water line.[8] It is common for there to be a high rate of mortality due to the moulting adult losing its grip on the substrate and ending up in a body of water where it can drown.[8]

Emergence occurs during the day from the months of October to February, with the majority bursting around January.[13] However adults can be found at late as May in Dunedin and in early June in Northland.[8] After emergence and maiden flight, young adults mature sexually for several days; during this time there can be quite a high number of dispersals.[8] Once males reach maturity they venture out to find habitats suitable for breeding and to set their territories where they stay motionless on their established porch for extended periods of time until they are bothered by an intruder.[8] Early afternoons, the height of reproductive activity, you will see males go chasing after females that fly through their territory. The mating "wheel" lasts for 10 minutes, and egg-laying generally occurs in tandem; the pair land on a floating piece of vegetation and the female drives a shaft through the stem and into the pith.[9][8] She then lays 6–9 eggs, taking up to a minute. This is repeated and eggs are laid out either in close batches or spaced between one another. Once the nymphs, known as pronaiads, are hatched they begin to search for water so they can moult and release the second larval instar (about 2.3 mm long).[8] These nymphs are quite active swimmers; once they reach a later stage they roam about on the surface of detritus and vegetation on the bottom of ponds.[8]

Behaviour

The larvae are quite active due to their ability to perform jumping movements and when disturbed the larvae swim very rapidly with the legs held close to the body towards the bottom sediments in which it buries itself.[14][15]

They eat a range of prey including oligochaetes, rotifers, cyclopoids, copepods, ostracods, Chydorus sphaericus, Simocephalus vetulus elizabethae, water mites, Sigara species, Anisops species, damselfly larvae, and chironomid larvae.[15] The larvae of A. colensonis are also cannibalistic.[16] They catch other water insects by hiding amongst submerged vegetation and then ambushing their prey.[16]

A. colensonis has been found to show aggressive, agonistic behavior. Larvae remain still and sit in one spot for hours and are easily bothered by disturbance. Rowe observed captured larvae that were placed in aquariums where the larvae executed various forms of postures and motor patterns.[16] The larvae were perched on two separate straws, one vertical, the other horizontal; each larvae defended their territory from the other organism.[16] If larvae were put together in high numbers it was noted that they would lose legs or caudal lamellae on occasion in intraspecific interactions.[16] Attacks that would occur sometimes resulted in the severing of a seized appendage, however there were no signs of predation after the event.

As adults A. colensonis also exhibit thermoregulation behavior. There are two mechanisms involved: physiological colour changes and behavioural responses.[8] They change in the intensity of their blue colouration. Males are pale blue-purple earlier on in the morning or after being cool for several hours. However, as they warm first the thorax then the abdomen become a brighter blue.[8] Females that have warmed enough may also look bluish in colour.[9]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

The larvae of the New Zealand damselfly also have predators even though they are usually one of the more dominant species in their pooling area. The predators consist of fish and beetles that they hide from in weed and submerged vegetation.[15]

Humans also contribute significantly to New Zealand damselfly survival with their power to redirect streams, leaving dry ponds with larvae unable to survive and eggs unable to hatch. Natural events, such as droughts, can also cause ponds and streams to dry up with similarly deadly results for larvae and eggs.[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Austrolestes colensonis (White, 1846)". New Zealand Organisms Register (NZOR). http://www.nzor.org.nz/names/e3af1acb-d428-4aac-adb5-697233311885.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kimmins, Douglas Eric (1970). "A list of the type-specimens of Odonata in the British Museum (Natural History) Part III". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Entomology 24: 171–205. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.1521. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2314341.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Parkinson B. J. & Horne D. (2007). A photographic guide to insects of New Zealand. New Holland.. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781869661519.

- ↑ White, Adam (1844–1875). "Insects". in Richardson, John. The zoology of the voyage of the H.M.S. Erebus & Terror, under the command of Captain Sir James Clark Ross, during the years 1839 to 1843. By authority of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.. 2. London: E. W. Janson. pp. Tab. 6. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7364. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/6962842.

- ↑ Sélys-Longchamps, Michel-Edmond (1860–65). Synopsis des agrionines. 2. Bruxelles. pp. 44. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.66021. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/42186521.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hudson, George (1904). New Zealand Neuroptera : a popular introduction to the life-histories and habits of may-flies, dragon-flies, caddis-flies and allied insects inhabiting New Zealand, including notes on their relation to angling. London: West, Newman & Co.. pp. 19–20, plate III. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.8516. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8645599.

- ↑ Tillyard, R.J. (1913). "On some new and rare Australian Agrionidae (Odonata)". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 37: 404–479 [421]. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.22352. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2903653.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 Rowe, Richard J.; Corbet, Philip S.; Winstanley, W. J. (1987). The dragonflies of New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 1869400038. OCLC 59837832.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Marinov, Milen; Ashbee, Mike (2019). Dragonflies and Damselflies of New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press. ISBN 978-1-86940-892-3. OCLC 1093850386. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1093850386.

- ↑ "Blue damselfly" (in en). http://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/resources/identification/animals/freshwater-invertebrates/guide/jointed-legs/insects-and-springtails/dragonflies-and-damselflies/blue-damselfly.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Deacon, K.J. (1979). The Seasonality of four Odonata species from mid Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Canterbury University. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ↑ Balance, Alison (17 December 2015). "Damselflies - fast blue and slow red". https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ourchangingworld/audio/201782907/damselflies-fast-blue-and-slow-red.

- ↑ Crowe, Andrew (2002). Which New Zealand insect? : with over 650 life-size photos of New Zealand insects. Auckland, N.Z.: Penguin. p. 78. ISBN 0141006366. OCLC 52477325.

- ↑ Rowe, R. J. (January 1985). "Intraspecific interactions of New Zealand damselfly larvae I. Xanthocnemis zealandica, Ischnura aurora, and Austrolestes colensonis (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae: Lestidae)" (in en). New Zealand Journal of Zoology 12 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/03014223.1985.10428263. ISSN 0301-4223.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Crumpton, Joy (April 1979). "Aspects of the biology of Xanthocnemis zealandica and Austrolestes colensonis (Odonata: Zygoptera) at three ponds in the South Island, New Zealand" (in en). New Zealand Journal of Zoology 6 (2): 285–297. doi:10.1080/03014223.1979.10428367. ISSN 0301-4223.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Rowe, R. J. (January 1992). "Agonistic behaviour in final-instar larvae of Austrolestes colensonis (Odonata: Lestidae)" (in en). New Zealand Journal of Zoology 19 (1–2): 1–5. doi:10.1080/03014223.1992.10423245. ISSN 0301-4223.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q2467682 entry

|