Biology:Banded surili

| Banded surili[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Presbytis femoralis robinsoni in Khao Sok National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Presbytis |

| Species: | P. femoralis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Presbytis femoralis (Martin, 1838)

| |

| |

| Banded surili range | |

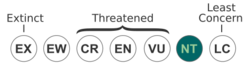

The banded surili (Presbytis femoralis), also known as the banded leaf monkey or banded langur, is a species of primate in the family Cercopithecidae. It is endemic to the Thai-Malay Peninsula and the Indonesia island of Sumatra.[2] It is threatened by habitat loss.[2]

Taxonomy

Three subspecies, femoralis (nominate), robinsoni and percura, are currently recognized,[1] but the taxonomy is complex and disputed,[3] and it has also included P. natunae, P. siamensis and P. chrysomelas as subspecies, or alternatively all these (including P. femoralis) have been considered subspecies of P. melalophos.[1] It is diurnal and eats fruit. Of the subspecies currently recognized, P. f. femoralis lives in Singapore and Johor in the southern Malay Peninsula, P. f. robinsoni lives in the northern Malay Peninsula, including southern Burma and Thailand, and P. f. percura lives in east-central Sumatra.[2][4]

In the past, some scientists, such as Oates, Davies and Delson (1994), regarded P. femoralis as a subspecies of the Sumatran surili (Presbytis melalophos).[5] Until 1984, the white-thighed surili (Presbytis siamensis) was considered a subspecies of the banded surili.[6] This would have covered the Natuna Island surili (Presbytis natunae), which was only deemed to be separate from the white-thighed surili in 2001.[7] The white-thighed surili has a range in Malaysia between the ranges of P. f. femoralis and P. f. robinsoni.[8][9] In Thailand, individual white-thighed suurilis are sometimes found within the range of P. f. robinsoni.[9] A 2010 genetic study by Vun, et al. suggested that P. f. robinsoni may be more closely related to the white-thighed surili than to P. f. femoralis.[10]

William Charles Linnaeus Martin formally described P. femoralis based on material that had been collected by Sir Stamford Raffles in Singapore.[11] Martin had given the distribution as "Sumatra etc.", not mentioning Singapore explicitly, resulting in some confusion over the actual type locality.[11][12] Gerrit Smith Miller resolved the issue in 1934, determining that Singapore was the actual type locality.[11][12]

Description

The banded surili is 432 to 610 millimetres (17.0 to 24.0 in) long, excluding the tail, with a tail length of 610 to 838 millimetres (24.0 to 33.0 in).[13] It weighs 5.9 to 8.2 kilograms (13 to 18 lb).[13] It has dark fur on the back and sides with lighter fur on the underside.[8] P. f. femoralis, sometimes known as Raffles' banded langur, has particularly dark fur on top and particularly white fur on the belly.[8] P. f. robinsoni, sometimes known as Robinson's banded langur, is more grey on the underside.[8]

Habits

The banded surili is diurnal and arboreal, preferring rainforest with trees of the family Dipterocarpaceae.[8][13] It comes to the ground less frequently than most other leaf monkeys.[14] It lives in both primary and secondary forest, and also in swamp forests and mangrove forests, and even in rubber plantations.[13] It moves primarily by walking on all fours and by leaping.[13]

According to wildlife researcher Charles Francis, it typically lives in groups of 3 to 6.[8] However, a study in Perawang, Sumatra found an average group size of 11 monkeys in mixed-sex groups.[15] The latter study also found an average ratio of 1 adult male to 4.8 adult females in mixed-sex groups and a ratio of 1.25 adult monkeys for every immature monkey in mixed-sex groups.[15] It also found an average range size for a group of 22 hectares, and an average population density of 42 monkeys per square kilometer.[15] Other studies found somewhat smaller home ranges, of between 9 and 21 hectares.[13]

The banded surili has a primarily vegetarian diet. Specialized bacteria in its gut allow it to digest leaves and unripe fruit.[14] The Perawang study found that nearly 60% of the diet consisted of fruits and seeds.[15] Another 30% consisted of leaves, primarily young leaves.[15] A different study found that fruit made up 49% of the diet.[13] Unlike some other monkeys, such as the long-tailed macaque, the banded langur destroys the seeds it eats, and so it is not a significant factor in dispersing seeds.[16]

The banded surili does not have a specific breeding season.[15] Infants are weaned at the age of 9 to 10 months old.[15] The infants often benefit from alloparenting for up to the first 3 months of their lives.[15] The Perawang study found that in the first month of their lives, infants are held by adults other than their mother about a third of the time.[15] Males leave their natal group before reaching maturity, at about 4 years old.[5][14]

The call of mature males sounds like "ke-ke-ke."[8] Mammalogist Ronald M. Nowak described the species' alarm call as "a harsh rattle followed by a loud chak-chak-chak-chak."[5]

Singapore population

The banded surili was once common throughout the island of Singapore but that population is now critically endangered with approximately 40 to 60 individuals left in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve.[17][18][19][14] The species was formerly found in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, but that population died out in 1987.[20] The last individual to live in Bukit Timah is now displayed at the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research.[20][21] The Central Catchment population had declined to as few as 10-15 monkeys before recovering to about 40 by 2012.[18]

The main threat to the Singapore population appears to be habitat loss.[22] 99.8% of Singapore's original primary forest, including much of its dipterocarp flora, has been eliminated, with less than 200 ha remaining, primarily in Bukhit Timah and the MacRitchie Reservoir and Nee Soon Swamp Forest portions of Central Catchment.[23] The Nee Soon Swamp Forest is the primary area of Central Catchment where the banded surili is found.[24][25] The monkey groups inhabit forest fragments that have limited arboreal connections to other fragments.[26] Other contributors to the species' decline in Singapore have been hunting for food and the pet trade.[19] The species has been legally protected in Singapore since 1947.[23] The Singapore government hopes that the development of Thomson Nature Park near Central Catchment will help maintain the banded leaf monkey population, since it is located near a traditional feeding area for the monkeys and will increase the forested area they can use.[27][28][29] They also hope that eventually when the vegetation matures the Eco-Link@BKE will allow banded leaf monkeys to repopulate Bukit Timah.[30]

The Singapore population feeds from at least 27 plant species, including Hevea brasiliensis leaves, Adinandra dumosa flowers and Nephelium lappaceum fruits.[4][26] They appear to prefer specific fruits and will travel long distances to reach their preferred fruit, rather than settle for more accessible foods.[19] The National Biodiversity Centre, in partnership with the Evolution Lab of the National University of Singapore, launched an ecological study to determine suitable conservation strategies. A 2012 study found extremely low genetic diversity within the remaining Singapore population and suggested that translocation of banded surilis from Malaysia may be necessary to provide the Singapore population with enough genetic diversity to survive in the long run.[18]

An earlier study had found that at least six infants had been born in the Singapore population over the years 2008-2010, with at least one birthing season occurring regularly in June and July.[31] That study found low infant mortality, with several infants surviving at least to seven months old.[31] The study also found that the infant coloration of the Singapore population is indistinguishable from that of the Johor, Malaysia population, with infants having white fur with a black stripe down the back from the head to the tail, crossed by another black stripe across the shoulders and to the forearms.[31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M.. eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100648.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Nijman, V.; Geissman, T.; Meijaard, E. (2008). "Presbytis femoralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T18126A7665311. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T18126A7665311.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/18126/7665311.

- ↑ Brandon-Jones, D., Eudey, A. A., Geissmann, T., Groves, C. P., Melnick, D. J., Morales, J. C., Shekelle, M. and Stewart, C.-B. 2004. Asian primate classification. International Journal of Primatology 25(1): 97-164.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Andie Ang Primatologist". Andie Ang. http://www.andieang.org/#!banded-leaf-monkey/cm45. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0801862519. https://archive.org/details/walkersprimateso0000nowa/page/159.

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M.. eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100673.

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M.. eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100663.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Francis, C.M. (2008). A Guide to the Mammals of Southeast Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 78, 263–265. ISBN 9780691135519.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Nijman, V.; Geissman, T.; Meijaard, E. (2008). "Presbytis siamensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T18134A7668889. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T18134A7668889.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/18134/7668889.

- ↑ Vun, V.F. (2011). "Phylogenetic relationships of leaf monkeys (Presbytis; Colobinae) based on cytochrome b and 12S rRNA genes". Genetics and Molecular Research 10 (1): 368–381. doi:10.4238/vol10-1gmr1048. PMID 21365553.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Low, M.E.Y. & Lim K.K.P. (30 October 2015). "The Authorship and Type Locality of the Banded Leaf Monkey, Presbytis Femoralis". Nature in Singapore 8: 69–71. https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/app/uploads/2017/06/2015nis069-071.pdf. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Miller, Gerrit S. (May 1934). "The Langurs of the Presbytis Femoralis Group". Journal of Mammalogy 15 (2): 124–137. doi:10.2307/1373983.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Rowe, N. (1996). A Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. Pogonias Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0964882508. https://archive.org/details/pictorialguideto0000rowe.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Attenborough, David (2019). Wild City:Forest Life. Channel NewsAsia.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Kirkpatrick, R.C. (2007). "The Asian Colobines". Primates in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–223. ISBN 9780195171334.

- ↑ Corlett, R.T. & Lucas, P.W.. "Mammals of Bukit Timah". The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore Supplement No. 3. Singapore Botanic Gardens: National Parks Board. p. 98. http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/dna/docs/fb6050e4ee025362a43a216afd6af802.pdf. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- ↑ "Ang Hui Fang's Banded Leaf Monkey work in The Straits Times - The Biodiversity Crew @ NUS". The Biodiversity Crew @ NUS. 2010-04-12. http://nusbiodiversity.wordpress.com/2010/04/12/hui-fangs-banded-leaf-monkey-work-in-the-straits-times/. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ang A.; Srivasthan A.; Md.-Zain B.; Ismail M.; Meier R. (2012). "Low genetic variability in the recovering urban banded leaf monkey population of Singapore". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 60 (2): 589–594. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259189658. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Ang, A. (July-September 2010). "Living Treasures in the Tree Tops: A Fresh Look at Singapore's Banded Leaf Monkeys". BeMuse Magazine (Splash Publishing): pp. 46–50. https://issuu.com/splash/docs/bemuse_july-sept_lowres. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Hope remains for last monkeys". Singapore Press Holdings. April 8, 2002. http://www.ecologyasia.com/news-archives/2002/apr-02/straitstimes.asia1.com.sg_singapore_story_0,1870,112907,00.html. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ "Raffles' banded langur (Banded leaf monkey)". National Library Board Singapore. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1472_2009-02-26.html. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ↑ "Singapore Red Data Book 2008:Banded Leaf Monkey". National Parks Board. http://www.nparks.gov.sg/cms/docs/redbook/presbytis-femoralis.pdf. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Corlett, Richard T. (July 1992). "The Ecological Transformation of Singapore, 1819-1990". Journal of Biogeography 19 (4): 411–420. doi:10.2307/2845569.

- ↑ Min, Chew Hui & Pazos, Rebecca (December 11, 2015). "Animals Crossing". Straits Times. https://graphics.straitstimes.com/STI/STIMEDIA/Interactives/2015/11/feature-ecolink-BKE-national-parks/index.html. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ↑ Ng, Peter & Lim, Kelvin (September 1992). "The conservation status of the Nee Soon freshwater swamp forest of Singapore". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2 (3): 255–266. doi:10.1002/aqc.3270020305.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Ang, A.; D'Rozario, V. (2016z). "Species Action Plan for the Conservation of Raffles' Banded Langur (Presbytis femoralis femoralis) in Malaysia and Singapore". IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/1200343/27337009/1479355170030/2016Nov17_Pff_Species+Action+Plan_Final.pdf?token=t2qZZG2om4zsaXUp2Q6mD9Z7mhw%3D. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ↑ Tan, Audrey (April 11, 2016). "More parks to save shy monkey from extinction". Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/more-parks-to-save-shy-monkey-from-extinction. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ↑ "NParks announces plans for Upcoming Thomson Nature Park". National Parks Board. October 8, 2016. https://www.nparks.gov.sg/news/2016/10/nparks-announces-plans-for-upcoming-thomson-nature-park. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ↑ "Media Fact Sheet A: Thomson Nature Park". National Parks Board. https://www.nparks.gov.sg/-/media/nparks-real-content/news/2016/thomson-nature-park/02-factsheetthomson-nature-park.pdf. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ↑ "Eco-Link@BKE". National Parks Board. https://www.nparks.gov.sg/news/2015/11/factsheet-eco-link-at-bke. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Ang, A.; Ismail, M.; Meier, R. (2010). "Reproduction and infant pelage coloration of the banded leaf monkey, Presbytis femoralis (Mammalia: Primates: Cercopithecidae) in Singapore". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 58 (2): 411–415. http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/rbz/biblio/58/58rbz411-415.pdf. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

Wikidata ☰ Q374384 entry