Biology:Benjamina (hominin)

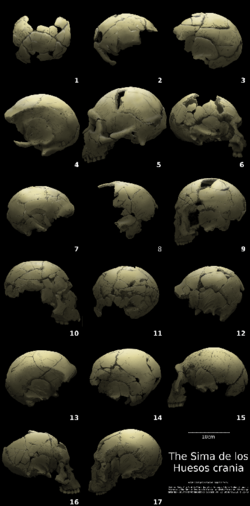

Cranium 14 as seen in the middle of the row second to the bottom. | |

| Catalog no. | SH 14 |

|---|---|

| Common name | Benjamina |

| Species | Homo neanderthalensis |

| Age | 530 ka |

| Place discovered | Atapuerca, Spain |

| Date discovered | 2001–2002 |

| Discovered by | Ana Gracia Téllez |

Benjamina is the nickname of a skull belonging to an early Neanderthal[1] child that is the earliest documented case of lambdoid craniosynostosis in the human fossil record. It was recovered from Sima de los Huesos, Spain , aged around 530 ka, minimum.[2] It has many catalogues, such as Sima de los Huesos 14, SH 14, Cranium 14, and Cr14.

History

During the field sessions of 2001–2002, the cranium was discovered, broken, by Ana Gracia Téllez and shattered into in many pieces in the laboratory. Its excavators were aware of its infantile state and recognized the specimen's importance.[3] Subsequent reconstruction over the following years found the specimen to be a near-complete neurocranium. It is nicknamed Benjamina because it is the feminine variation of Benjamín, a Hebrew name that allocates the "favorite member of a family" and is often given to the youngest child in the family.[2]

Unlike the fate of many disabled children in human history, Benjamina reached at last ten years of age. Despite having been visibly disfigured, the group probably cared for and allowed for them to reach a relatively advanced age. The discovery is significant in that it is the earliest case of craniosynostosis and an early case of human social care.[2] Benjamina may have had walking difficulties that would have needed more than their parents could have provided, suggesting communal care.[3]

Description

Benjamina is complete aside from the face, right occipital condyle, ethmoid, central sphenoid, petrous and mastoid processes.[4] Based on the spheno-occipital and jugular synchondroses, the specimen was not an adult at death. only being around 10-12 years of age. The cranial capacity of the specimen is 1200 centimeters cubed. The skull has a small wormian bone, which was caused by pathologies in the specimen, in a gap formed between the lambdoid suture. This gap is quite wide, which indicates that an additional supernumerary ossicle may have been present.[2]

Pathology

After reconstruction, it was discovered that 2/3 of the left lateral and medial areas of the lambdoid suture. This birth defect is true lambdoid craniosynostosis, which, unnaturally, thickens the contralateral parietal and right frontal, bulges the ipsilateral occipitomastoid, and tilts the entire skull ipsilaterally downward towards the cranial base. The aforementioned thickening of the frontal greatly raises the forehead, creating a superficial resemblance with Homo sapiens. Frequently reported in cases of craniosynostosis is a wormian bone, which this specimen has right of the lambdoid suture.[2]

The internal surface of the cranium bears defined endocranial convolutions and suggested expanded subarachnoid spaces, which can be found in people living with positional plagiocephaly, or true craniosynostosis. Study of the specimen by Gracia et al. suggests that various causations for the synostosis (intrauterine trauma, fetal head constraint, torticollis congenita). One of which, fetal head constraint, is caused due to a lack of amniotic fluid. The skull may have deformed during week 28 of the third trimester and was probably born with the skull already abnormally fusing in place.[3] Metabolic diseases such as anemia or rickets are not supported as causes because they do not alter the bone shape in their subjects.[2] It is important to note that none of the Sima de los Huesos sample aside from this fossil are not deformed postmortem. The amount these conditions affected the abilities of the individual,[4] as these conditions may damage the brain.[3]

References

- ↑ Stringer, Chris (2012). "The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908)" (in en). Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 21 (3): 101–107. doi:10.1002/evan.21311. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/evan.21311.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Gracia, Ana; Martínez-Lage, Juan F.; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; Martínez, Ignacio; Lorenzo, Carlos; Pérez-Espejo, Miguel-Ángel (2010-06-01). "The earliest evidence of true lambdoid craniosynostosis: the case of “Benjamina”, a Homo heidelbergensis child" (in en). Child's Nervous System 26 (6): 723–727. doi:10.1007/s00381-010-1133-y. ISSN 1433-0350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-010-1133-y.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Romero, Lorena Sánchez (2020-11-27). "Prehistoria - Benjamina, la niña pre neandertal más querida de Atapuerca" (in es). https://quo.eldiario.es/ser-humano/q2011650310/neandertal-atapuerca-benjamina/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gracia, Ana; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Martínez, Ignacio; Lorenzo, Carlos; Carretero, José Miguel; Bermúdez de Castro, José María; Carbonell, Eudald (2009-04-21). "Craniosynostosis in the Middle Pleistocene human Cranium 14 from the Sima de los Huesos, Atapuerca, Spain" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (16): 6573–6578. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900965106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 19332773. PMC 2672549. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0900965106.

|