Biology:Capsella bursa-pastoris

| Shepherd's purse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flowering and fruiting | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Brassicales |

| Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Genus: | Capsella |

| Species: | C. bursa-pastoris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik.

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

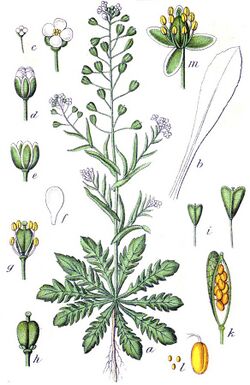

Capsella bursa-pastoris, known as shepherd's purse because of its triangular flat fruits, which are purse-like, is a small annual and ruderal flowering plant in the mustard family (Brassicaceae).[2] It is native to eastern Europe and Asia minor,[3] but is naturalized and considered a common weed in many parts of the world, especially in colder climates,[4] including British Isles,[5] where it is regarded as an archaeophyte,[6][7] North America[8][9] and China,[10] but also in the Mediterranean and North Africa.[3] C. bursa-pastoris is the second-most prolific wild plant in the world,[10] and is common on cultivated ground and waysides and meadows.[11]

Scientists have referred to this species as a "protocarnivore", since it has been found that its seeds attract and kill nematodes as a means to locally enrich the soil.[12][13]

History

Pictured and published in 1486.[14]

Description

Capsella bursa-pastoris plants grow from a rosette of lobed leaves at the base. From the base emerges a stem about 0.2–0.5 m (0.66–1.64 ft) tall, which bears a few pointed leaves which partly grasp the stem. The flowers, which appear in any month of the year in the British Isles,[11]:56 are white and small, 2.5 mm (0.098 in) in diameter, with four petals and six stamens.[11] They are borne in loose racemes, and produce flattened, two-chambered seed pods known as silicles, which are triangular to heart-shaped, each containing several seeds.[9]

Like a number of other plants in several plant families, its seeds contain a substance known as mucilage, a condition known as myxospermy.[15] Recently, this has been demonstrated experimentally to perform the function of trapping nematodes, as a form of 'protocarnivory'.[12][13][16]

Capsella bursa-pastoris is closely related to the model organism such as Arabidopsis thaliana and is also used as a model organism, due to the variety of genes expressed throughout its life cycle that can be compared to genes that are well studied in A. thaliana. Unlike most flowering plants, it flowers almost all year round.[9][10] Like other annual ruderals exploiting disturbed ground, C. bursa-pastoris reproduces entirely from seed, has a long soil seed bank,[6] and short generation time,[3] and is capable of producing several generations each year.

Taxonomy

It was formally described by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in his seminal publication Species Plantarum in 1753, and then published by Friedrich Kasimir Medikus in Pflanzen-Gattungen (Pfl.-Gatt.) on page 85 in 1792.[17][18]

Capsella bursa-pastoris subsp. thracicus (Velen.) Stoj. & Stef. is the only known subspecies.[17]

William Coles wrote in his book, Adam in Eden (1657), "It is called Shepherd's purse or Scrip (wallet) from the likeness of the seed hath with that kind of leathearne bag, wherein Shepherds carry their Victualls [food and drink] into the field."[19]

In England and Scotland, it was once commonly called 'mother's heart', from which was derived a child's game/trick of picking the seed pod, which then would burst and the child would be accused of 'breaking his mother's heart'.[19]

Uses

Capsella bursa-pastoris gathered from the wild or cultivated[20][21] has many uses, including for food,[10][21] to supplement animal feed,[20] for cosmetics,[20] and in traditional medicine[10][20]—reportedly to stop bleeding.[22] The plant can be eaten raw;[23] the leaves are best when gathered young.[24] Native Americans ground it into a meal and made a beverage from it.[22]

Cooking

It is cultivated as a commercial food crop in Asia. [25] In China, where it is known as jìcài (荠菜; 薺菜) it is commonly used in food in Shanghai and the surrounding Jiangnan region. The savory leaf is stir-fried with rice cakes and other ingredients or as part of the filling in wontons.[26] It is one of the ingredients of the symbolic dish consumed in the Japanese spring-time festival, Nanakusa-no-sekku. In Korea, it is known as naengi (냉이) and used as a root vegetable in the characteristic Korean dish, namul (fresh greens and wild vegetables).[27]

The seeds of shepherd's purse were used as a pepper substitute in colonial New England.[28]

Chemistry

Fumaric acid is one chemical substance that has been isolated from C. bursa-pastoris.[29]

Pathogens

Pathogens of this plant include:[citation needed]

- White rust Albugo candida

- One species of downy mildew Hyaloperonospora parasitica

- Phoma herbarum[30]

References

- ↑ "Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik.". Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30092589-2#synonyms.

- ↑ Parnell, J.; Curtis, T. (2012). Webb's An Irish Flora. Cork University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-185918-4783.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Aksoy, A; Dixon, JM; Hale, WH (1998). "Biological flora of the British Isles. Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medikus (Thlaspi bursapastoris L., Bursa bursa-pastoris (L.) Shull, Bursa pastoris (L.) Weber)". Journal of Ecology 86: 171–186. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.1998.00260.x.

- ↑ "Capsella bursa-pastoris". http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=5&taxon_id=200009292.

- ↑ Clapham, A.R., Tutin, T.G. and Warburg, E.F. 1968. Excursion Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN:0-521-04656-4

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Preston, CD; Pearman, DA; Dines, TD (2002). New Atlas of the British & Irish Flora. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198510673.

- ↑ Preston, CD; Pearman, DA; Hall, AR (2004). "Archaeophytes in Britain". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 145 (3): 257–294. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00284.x.

- ↑ "Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik". https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=CABU2.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Capsella bursa-pastoris". http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=200009292.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 Clapham, A.R.; Tutin, T.G.; Warburg, E.F. (1981). Excursion Flora of the British Isles (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521232906.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Nature - Evidence for Facultative Protocarnivory in Capsella bursa-pastoris seeds

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Telegraph - Tomatoes Can Eat Insects

- ↑ Morton, A.G. (1981). History of Botanical Science'. Academic Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0125083823. https://archive.org/details/historyofbotanic0000mort/page/96/mode/2up.

- ↑ Tamara L. Western; Debra J. Skinner; George W. Haughn (February 2000). "Differentiation of Mucilage Secretory Cells of the Arabidopsis Seed Coat". Plant Physiology 122 (2): 345–355. doi:10.1104/pp.122.2.345. PMID 10677428.

- ↑ Barber, J.T. (1978). "Capsella bursa-pastoris seeds: Are they "carnivorous"?". Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 7 (2): 39–42. http://www.carnivorousplants.org/cpn/articles/CPNv07n2p39_42.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 "Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. is an accepted name". theplantlist.org. 23 March 2012. http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-2697999.

- ↑ "Brassicaceae Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik". ipni.org. http://www.ipni.org/ipni/idPlantNameSearch.do?id=279929-1.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Reader's Digest Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. Reader's Digest. 1981. p. 54. ISBN 9780276002175.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 "Capsella bursa-pastoris (Ecocrop code 4164)". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/dataSheet?id=4164.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 "Capsella bursa-pastoris - (L.)Medik". http://www.pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Capsella+bursa-pastoris.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 Nyerges, Christopher (2017). Foraging Washington: Finding, Identifying, and Preparing Edible Wild Foods. Guilford, CT: Falcon Guides. ISBN 978-1-4930-2534-3. OCLC 965922681.

- ↑ Nyerges, Christopher (2016). Foraging Wild Edible Plants of North America: More than 150 Delicious Recipes Using Nature's Edibles. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4930-1499-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=RwDHCgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Benoliel, Doug (2011). Northwest Foraging: The Classic Guide to Edible Plants of the Pacific Northwest (Rev. and updated ed.). Seattle, WA: Skipstone. pp. 139. ISBN 978-1-59485-366-1. OCLC 668195076. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/668195076.

- ↑ Mills, David (March 11, 2014). Nature's Restaurant: Fields, Forests & Wetlands Foods of Eastern North America - A Complete Wild Food Guide. http://natures-restaurant-online.com/ShepherdsPurse.html.

- ↑ Samuels, Debra (12 May 2015). "This Chinese grandma forages and cooks". bostonglobe.com. https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/food-dining/2015/05/12/this-chinese-grandma-forages-and-cooks/Aw3Nl9IUj4UpaJi4UN9feI/story.html.

- ↑ Pratt Keith L.; Richard Rutt; James Hoare (1999). Korea: a historical and cultural dictionary. Richmond, Surrey.: Curzon Press. pp. 310. ISBN 978-0-7007-0464-4.

- ↑ Hussey, Jane Strickland (Jul–Sep 1974). "Some Useful Plants of Early New England". Economic Botany 28 (3): 311–337. doi:10.1007/BF02861428.

- ↑ Kuroda, K.; Akao, M.; Kanisawa, M.; Miyaki, K. (1976). "Inhibitory effect of Capsella bursa-pastoris extract on growth of Ehrlich solid tumor in mice". Cancer Research 36 (6): 1900–1903. PMID 1268843.

- ↑ Helgi Hallgrímsson & Guðríður Gyða Eyjólfsdóttir (2004). Íslenskt sveppatal I - smásveppir [Checklist of Icelandic Fungi I - Microfungi. Fjölrit Náttúrufræðistofnunar. Náttúrufræðistofnun Íslands [Icelandic Institute of Natural History]. ISSN 1027-832X

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q27264 entry

|