Biology:Carolina heelsplitter

| Carolina heelsplitter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Lasmigona |

| Species: | L. decorata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lasmigona decorata (I. Lea, 1852)

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The Carolina heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata) is a species of freshwater mussel, an aquatic bivalve mollusk in the family Unionidae.

It is named the "Carolina heelsplitter" because in life the sharp edge of the valves protrudes from the substrate and could cut the foot of someone walking on the river or stream bed.

This species is endemic to the United States and is found in only North Carolina and South Carolina.

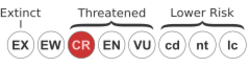

This species' current status is classified as "critically endangered". The IUCN Red List website states that to be considered critically endangered, the species must face an extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild in the immediate future.[1]

Description

The first recorded encounter with the Carolina heelsplitter was in 1852 by Isaac Lea. He described this new creature as Unio decoratus. The largest recorded specimen was about five inches long.

This freshwater mussel has a shell which is greenish-brown to dark brown on the outside. The inside of the shell usually has nacre that is pearly white or bluish-white, although the nacre can be pale orange in older specimens. The younger individuals tend to have faint black or greenish-brown rays on the outer surface of the shell.

This medium-sized mussel has well-developed, but thin, lateral teeth that are somewhat delicate. The Carolina heelsplitter also has two blade-like pseudocardinal teeth in the left valve, and one in the right valve.

With an “ovate, trapezoid-shaped, unsculptured shell“, the size of the largest Carolina heelsplitter currently is about 4.6 inches (12 cm) in length and 1.56 inches (4.0 cm) in width, with a height of 2.7 inches (6.9 cm).[citation needed]

Endangered Species Act and Recovery Plan

This species was determined to be endangered on Wednesday, June 30, 1993. The reasons stated were: “Present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range”, “over utilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes”, “disease or predation”, “the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms”, and “other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence”. There has since been a review of the species and how it has been recovering, dated July 28, 2006.

The original recovery plan for the species was written by John A. Fridell and recognized in January 1997. The major points were using government regulations to protect the species, creating educational opportunities, continuing to search for new populations, establishing six viable populations, and alleviating major threats to the species, with the final objective being to get the species de-listed.

When the recovery plan was written, there were only four known populations of Lasmigona decorata. The original report stated that the populations appeared to have extremely restricted distribution and that much of the habitat in the species historic range (Catawba, Pee Dee, Saluda, and Savannah River systems) is now unsuitable for the reintroduction of the species. The recovery plan also stated that it was very important that the species were extensively enough established so the population couldn't be completely wiped out by one major event involving their habitat.

Reproduction

The reproductive cycle begins when the male Carolina heelsplitter releases its sperm into the stream. Soon afterwards the sperm is taken in by the females, a process which is called siphoning. The female's eggs, which will be carried in the female's gills, are then fertilized. The Carolina heelsplitter is a bradytichtic species, brooding fertilized eggs over the winter after spawning.[5] When the glochidia (larvae) are fully developed the next year, the female mussel releases them into the water. The larvae must attach themselves quickly to a body part of their host fish, which is not harmed in the process. Host species for this mussel include members of the Cyprinidae.[6]

Attached to the fish, the heelsplitters receive oxygen and other needs from the host for several weeks. When they have grown into fully developed juvenile mussels, they release themselves from the fish and settle into the stream or river.

A fish host is very important to all mussels, not only because it provides the young with food and oxygen, but also because it serves as a mode of transportation. The transportation of the mussels is key when attempting to create new populations in streams and river banks. Thus this creature can seed the fresh waters and have more larvae.

Location and distribution

The Carolina heelsplitter lives in shallow streams and rivers, and occasionally, a pond. The species can usually be found in mud, or mixed sediments. They are usually found along stable stream banks, but have also been found in the middle of a water way. It is important that the water does not carry much sediment.

Historically the Carolina heelsplitter was known to be found in the Catawba River and Pee Dee River systems in North Carolina, and the Pee Dee and Savannah River systems of South Carolina. It is also possible that these mussels historically lived in the Saluda River systems in South Carolina.

There are currently ten known populations (prior to the 2007–2008 drought) in North Carolina and South Carolina. The areas include Goose Creek and Flat Creek in the Pee Dee River system, Waxhaw Creek, Sixmile Creek, Gills Creek, Fishing Creek, and Bull Run Creek in the Catawba River system, and Red Bank Creek, Turkey Creek, and Cuffytown Creek all located in the Saluda River system.

John A. Fridell states that the numbers of individuals in every population is very small:

- 1–17 individuals were found in eight of the known populations, with only 1–5 individuals being found in four of these eight populations.

- 26 individuals were found in only one population

- The largest population included only 42 individuals.

The numbers that the surveyors found also indicate that the species is in decline, and also that none of the populations have improved over time. John A. Fridell also mentions that the populations are very highly fragmented and isolated, and that they have also only been found in short stream reaches of each other.

Many combined influences are connected to the decline and endangerment of the Lasmigona decorata populations. The biggest reasons for their critical endangerment are due to sedimentation and stream pollution, road construction and maintenance, runoff, mining, and several other human generated problems.

Threats and reasons for endangerment

Population size

One of the main reasons that the Carolina heelsplitter has such a high risk of going extinct is its population size. Currently the number of individuals in each population is low, and are distant from one another, such that they have little opportunity to mingle genes. This may mean that there is not enough genetic material for them to be able to adapt properly to natural and manmade challenges.

Water pollution

Clean and unpolluted water is very important to the Carolina heelsplitters. Chemical water pollution can be the most serious threat. This can include runoff, dumping trash or chemicals into the stream and rivers, and other sources. Mussel larvae and juveniles are extremely sensitive to high levels of copper and ammonia, but seem to tolerate slightly higher levels of chlorine.[citation needed] The most elevated levels of ammonia were found at the stations at Goose Creek, as were the highest chlorine and copper levels. The research group thought that the higher levels of copper were due to more suspended sediment because of a recent rain downpour.

Habitat degradation

The Carolina heelsplitter is now found in shallow streams and rivers ranging from about one to four feet deep. The water has to be clear, without culverts, dams, or anything that might obstruct the flow of the river. The rivers must have high oxygen content with a lot of microscopic organisms and plants to feed on.

These mussels need to live near very stable river or stream banks. Crumbling banks not only take away home territory for this group of mussels, but a stable stream bank system also means that many plants and trees live near the stream banks and hold the soil and sediment in place with their roots. Any rise of silt or sediments in the rushing water can have a detrimental effect on the species and too much sediment will smother and kill the mussels.

Any kind of human development such as bridges etc. on or near the rivers greatly disturbs the delicate balance of the carried sediment in the water.

The vegetation along the river and stream sides also help regulate the water's temperature during the long and hot summers. It also provides decaying leaves and plants that are an essential part to the survival of all organisms living in the water.

Expansion and development

Both expansion and development greatly affect the Carolina heelsplitter, as it does most species. Such human interventions as channelization, impoundments and stream dredging harm the species by directly destroying its habitat.

The fish host

If it is possible to find out what species of fish serves as the fish host for the larvae of the Carolina heelsplitters, then it will be possible to determine whether the fish host is endangered or over fished.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bogan, A.E. (1996). "Lasmigona decorata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1996: e.T11360A3273594. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T11360A3273594.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/11360/3273594. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ↑ "Carolina heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata)". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/3534.

- ↑ 58 FR 34926

- ↑ "Lasmigona decorata (Lea, 1852)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=80140.

- ↑ NatureServe (7 April 2023). "Lasmigona decorata". Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.117516/Lasmigona_decorata.

- ↑ "Lasmigona decorata glochidia and infestation". Raleigh: NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. http://www.aeclab.org/modules/info/lasmigona_decorata_glochidia_and_infestation.html.

- "Carolina heelsplitter." Species Profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [1].

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Carolina Heelsplitter Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA.

- "The Carolina Heelsplitter in the Carolinas." Library.fws.gov. December 2002. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [2].

- Price, Jennifer. "Carolina Heelsplitter." DNR. [3].

- Fridell, John A.. "Carolina Heelsplitter in North Carolina." U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. 2003. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. 8 Apr 2008 [4].

- Ward, Sara . Augspurger, Tom. Dwyer, F. James. Kane, Cindy. Ingersoll, Christopher G. "Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry." SETAC Journals Online. 2007. Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. [5].

- G. Booy, R. J. J. Hendriks, M. J. M. Smulders, J. M. Van Groenendael, B. Vosman (2000) Genetic Diversity and the Survival of Populations Plant Biology 2

- John Fridell

US Fish and Wildlife Service

- "Species Information and Status." North Carolina Mussel Atlas. North Carolina Wildlife. [6].

- "Discover Goose Creek and the Carolina Heelsplitter." North Carolina Wildlife. North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. [7][yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 5-Year Review of 19 Southeastern Species." Species Profile. 28 July 2006. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [8].

External links

- Information on Threatened and Endangered Species. Carolina heelsplitter, Lasmigona decorata. at webpage of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Wikidata ☰ Q3017695 entry

|