Biology:Cassin's sparrow

| Cassin's sparrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Peucaea |

| Species: | P. cassinii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Peucaea cassinii (Woodhouse, 1852)

| |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Aimophila cassinii | |

Cassin's sparrow (Peucaea cassinii) is a medium-sized sparrow.

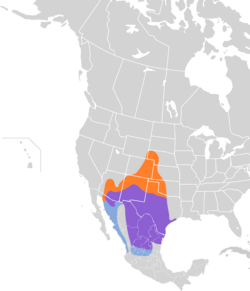

This passerine bird's range is from western Nebraska to north-central Mexico.

Taxonomy

The first Cassin's sparrow was described in 1852 by Samuel W. Woodhouse from a specimen collected near San Antonio, Texas , and given its species name in honor of John Cassin, a Philadelphia ornithologist.[3] The species was originally known as Zonotrichia cassinii.[4] It was subsequently and variously assigned to the genus Peucaea and eventually to Aimophila around the turn of the century.[5] Much of the confusion seems to have stemmed from a serious lack of knowledge about the anatomy and life history of the species included in the genus.[6]

There have been several substantial treatments of the taxonomy of species within the genus Aimophila[7] and a comparison of the song patterns of Aimophila sparrows,[8] but they have focused primarily on evaluating the evolutionary development of these species in order to determine whether this genus actually consists of an unnatural assemblage of species (actually representing several taxonomic groups or divergent forms).[9] None of these publications called into question the placement of Cassin's sparrow within this genus in what is called the "botterii complex" – Botteri's sparrow (Aimophila botterii), Bachman's sparrow (A. aestivalis), and Cassin's sparrow (A. cassinii).[6]

In 2010, the American Ornithologists' Union resurrected the genus Peucaea on the basis of genetic, morphological, and vocal data, moving Cassin's sparrow back to Peucaea cassinii.[10]

No subspecies or races of Cassin's sparrow are recognized.[11]

Description

The sparrow has a long tail, gray-brown with white corners, and has dark marks on the back and sides.[12] The species resembles Botteri's sparrow because of its size and marks, but Boterri's sparrow is a weaker shade of gray. The best way to tell the differences between the two is the song of Cassin's sparrow. Both the males and females are the same shade of gray and are 5 to 6 inches, although males are bigger.[13]

The Cassin's sparrow is a fairly large, plain, grayish sparrow that lacks conspicuous markings. In flight, the long, roundish tail is obvious and the white tips of the tail feathers are sometimes apparent. This species is most easily identified by its distinctive song and dramatic skylarking behavior during the breeding season. Although often characterized in the literature as secretive and difficult to observe when not singing,[14] (Schnase 1984) observed that Cassin's sparrows readily accommodated the presence of an observer, especially early in the breeding season.

Plumage

Adult

The head is brown streaked with gray and dark brown; the supercilium is buff, and there is a thin, dark brown submoustachial stripe. The bill is brownish gray, with darker upper mandible and pale bluish gray tomial edge and lower mandible. The iris is dark brown. The chin, throat and breast are pale gray or brownish gray; the belly is whitish; and there are a few well-defined dark brown or black streaks on the lower flanks. On the back, the mantle and scapulars are described as brown or gray with a rusty tinge, the feathers having dark brown subterminal spots and edged with buff or gray, giving a scaly or variegated appearance. Wings are brown; greater coverts are broadly tipped and narrowly edged with buff or grayish white, forming a wing bar variously described as fairly conspicuous to indistinct. The alula is pale yellow. Feathers in the upper tail coverts have a gray edge, a brown center, and a black subterminal crescent. The undertail coverts are buffy. Most of the upper side of the tail is dark, dusky brown, but the central two rectrices are pale brownish gray with a serrated dark central strip that spreads out into a suggestion of faint crossbars. The lateral two rectrices are edged and tipped in pale gray or white, with smaller pale areas at the tips of the next two pairs inward. This is sometimes noticeable on a bird flushing or flying away, but it is not always apparent, and by late summer, pale tips may be partly or completely worn away. Legs are described as dull pinkish or dark flesh.[15]

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to adults with a brown back, feathers with buffy tips and darker brown central streaks, greater coverts edged with white, and light streaking on breast and throat.[15]

Some birds, mainly in the eastern part of their range, tend to be more rufous above, slightly buffier below, and have plainer tails with less obvious shaft streaks and barring on the central rectrices.[16] Although rarer, even in the eastern part of the range, the rufous morph has been observed as far away as the Farallon Islands off California .[17]

Cassin's sparrows have an unusual sequence of molts and plumages. They replace all of their pennaceous body feathers twice within the bird's first six months of age, and adults gradually molt their body feathers throughout the breeding season.[18] Designated as a presupplemental molt, this molt has been fully documented in certain species only recently, having been found in 16 species of North American passerines to date.[19]

Natural history

Song

The sparrow's song sounds like titi-trrrrrrrrrrr, tyew tyew.[12] Only the males sing and the males are known for flying in the air and gliding down while singing which is called "skylarking". Males of the species are one of only a few sparrows known to skylark.[20] The book Heralds of Spring in Texas says that a clue that spring is coming in Midland County, Texas is "the high, sweet trills of Cassin's sparrows".[21] There is also a second flight song with chips which is only from adults when they are on edge. Chicks do a series of sips when they sing. The males sing from February to September[22] with the song of Cassin's sparrow being its most identifiable trait.[23]

The Cassin's sparrow's primary song consists of six note complexes, beginning with a soft double or single introductory note, followed by a long, high musical trill on one pitch, and (usually) two lower, well-spaced musical notes, all with a slight minor-key quality. There is enough individual variation in this song that it has been used as a means of identifying individual males in population studies.[24] A secondary song, or "chitter" song,[5] consists of a series of chips, trills, and buzzy notes preceding the primary song.[25] Cassin's sparrows also give a variety of chitter calls and chip notes that have been assigned various roles by different authors, including pair bond maintenance, communication with fledglings, alarm calls, territory defense, etc.[26] Unusual conditions may induce this species to sing at unusual times of year.[27]

Territorial males sit in low bushes or grass, or on the ground to sing, but often give spectacular flight-songs. At the beginning of the breeding season, all song is from a stationary, exposed perch and often involves reciprocal proclamation of the primary song among males. Flight songs and skylarking are infrequent until later, in association with the presence of returning females.[28] In flight songs (or skylarking), the territorial male flies up from an exposed perch, such as a bush, to as much as 5 – 10 m in the air, then sings as he glides or flutters down in an arc to a nearby bush or the ground. During the descent, wings are held flat, the head is arched backwards, and the tail is elevated. Song can be heard from mid-February to early September, depending on location, with considerable night singing at the height of the season reported by some.[29]

Diet

The bird's diet consists of insects and seeds.[30]

The summer diet of Cassin's sparrows consists primarily of insects, especially grasshoppers, caterpillars, and beetles. Additional insects specifically mentioned in the literature include true bugs, ants, bees, wasps, weevils, spiders, snails, and moths.[31] The young are fed almost entirely insects.[32] (Bock Bock) note that observations of a Cassin's sparrow nest for 18 hours in 1984 showed that of 208 insects delivered to nestlings, 197 (95%) were acridid grasshoppers. However, (Wolf 1977) reported that the stomachs of ten adults taken during the breeding season (late June and early July) contained animal and vegetable matter in about equal proportions (52% and 48%, respectively; range = 5–95%). He also found that five migrant Cassin's sparrow stomachs contained 99% animal material (range = 90–100%). There is a report of Cassin's sparrows eating flower buds of blackthorn bush (Condalia spathulata) in season.[33] In fall and winter, Cassin's sparrows eat the seeds of weeds and grasses.[34] (Oberholser 1974) particularly mentions the consumption of seeds of chickweed (family Alsinaceae), plantain (Plantago spp.), woodsorrel (Xanthoxalis spp.), sedge (Carex spp.), panicum (Panicum spp.), other grasses, and sorghum (Sorghum spp.).

(Schnase 1984) reports observing birds drinking water from a small pool immediately following a rain. Although (Williams LeSassier) report that Cassin's sparrows seem to exist very well without drinking water, their conclusion appears to be based on the limited number of recorded observations of this species drinking water, the distance of most nesting areas from water, and the fact that birds rarely leave their territories.[35]

Cassin's sparrows forage mostly or entirely on the ground, hopping about in relatively open areas, taking items from the ground or from plant stems.[36] When flushed, they fly to a bush or fence, or may drop back into the grass.[37] (Schnase 1984) reported that foraging occurred in a slow, methodical manner. Foliage gleaning from within mesquite (Prosopis spp.) and other shrubs was only prominent after nestlings and fledglings were present. Fledglings apparently acquired most of their food in this manner rather than on the ground.

Habitat

Cassin's sparrow can commonly be found in brushy grassland and is nomadic.[12] Between 1955 and 1989, there was a below average amount of this species although the number rises and falls each year.[38] The sparrow can be found in south-central states. It is known that the sparrow is rarely found in the northern part of its range which might be because of rainfall.[23]

The bird's nest is in grass and is a mixture of various weeds and grasses. The female lays from to 3 to 5 eggs.[39]

Although Cassin's sparrows use slightly different habitats in different parts of their range, the common denominator across all habitats seems to be that they require both a grass component (usually short grass) and a shrub component. The latter component may be actual shrub species [e.g., mesquite, sage (Artemisia spp.), hackberry (Celtis spp.), rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus spp.), or oaks (Quercus spp.)] or other vegetative forms that approximate shrub structure [e.g. yucca (Yucca spp.), paddle cacti (Opuntia spp.), ocotillo or bunch grasses].[40] The need for the structure provided by shrubs or similar plants is related to the bird's need for perches from which to sing or launch itself for its flight song and its frequent use of low shrubs for nest placement. (Schnase 1984) also noted that the mesquite thickets within Cassin's sparrow territories were distinctly preferred when fledglings were present. It appears that relative proportions of grass and shrubs in acceptable Cassin's sparrow habitat cover a wide range from grassland habitats with a very sparse distribution of shrubs to shrubland habitats with a grass cover.[41]

Notes

- ↑ BirdLife International (2016). "Peucaea cassinii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22721272A94705871. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22721272A94705871.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22721272/94705871. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Peucaea cassinii". Avibase. https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=B58AFD6EE6337146.

- ↑ Terres 1980.

- ↑ American Ornithologists' Union 1998.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Wolf 1977.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ruth 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ Wolf 1977, Storer 1955

- ↑ Borror 1971.

- ↑ Storer 1955.

- ↑ American Ornithologists' Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature—North and Middle America 2010, p. 738.

- ↑ Pyle 1997; American Ornithologists' Union 1957; Dunning et al. 2000; Ruth 2000, p. 3

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kaufman, Kenn (2000). Birds of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 340. ISBN 0-395-96464-4. https://archive.org/details/birdsofnorthamer00kenn.

- ↑ Rising 1996, p. 65.

- ↑ Williams & LeSassier 1968; Oberholser 1974; Kaufman 1990

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rising 1996; Byers, Curson & Olsson 1995; Kaufman 1990

- ↑ (Byers Curson)

- ↑ J. Dunning personal communication cited by (Ruth 2000)

- ↑ (Willoughby 1986)

- ↑ Pyle 1997.

- ↑ GirlScientist (June 8, 2011). "Mystery bird: Cassin's sparrow, Peucaea cassinii". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/punctuated-equilibrium/2011/jun/08/4.

- ↑ H. Wauer, Roland; Ralph Scott (1999). Heralds of Spring in Texas. Texas A&M University Press. p. 215. ISBN 9780890968796. https://archive.org/details/heraldsofspringi0000waue. Retrieved December 17, 2011. "cassin's sparrow."

- ↑ Rising 1996, p. 66.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Dunn, Jon; Jonathan K. Alderfer (2008). National Geographic field guide to the birds of western North America. National Geographic Books. p. 358. ISBN 9781426203312. https://books.google.com/books?id=5kVen0Hqgx0C&q=cassin%27s+sparrow&pg=PA358.

- ↑ Schnase & Maxwell 1989.

- ↑ Schnase 1984.

- ↑ Kaufman 1990; Schnase 1984; Wolf 1977

- ↑ Kaufman 1990.

- ↑ Schnase et al. 1991; Schnase 1984

- ↑ Rising 1996; Howell & Webb 1995; Schnase 1984; Oberholser 1974

- ↑ "Cassin's sparrow Aimophila cassinii". US Geological Survey. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/infocenter/i5780id.html.

- ↑ Dunning et al. 2000; Kaufman 1996; Bock, Bock & Grant 1992; Oberholser 1974; Williams & LeSassier 1968

- ↑ Kaufman 1996.

- ↑ Oberholser 1974.

- ↑ Kaufman 1996; Williams & LeSassier 1968

- ↑ Ruth 2000, p. 6.

- ↑ Kaufman 1996, Schnase 1984

- ↑ Rising 1996.

- ↑ "Region 2 Sensitive Species Evaluation Form". US Forest Service. http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/evalrationale/evaluations/birds/cassinssparrow.pdf.

- ↑ Rising 1996, p. 67.

- ↑ Baicich & Harrison 1997; Rising 1996; Williams & LeSassier 1968

- ↑ JMR cited by (Ruth 2000)

References

- "Aimophila cassinii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=179393. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- American Ornithologists' Union (1957), Check-list of North American Birds (5th ed.), Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union

- American Ornithologists' Union (1998), Check-list of North American Birds (7th ed.), Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union

- American Ornithologists' Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature—North and Middle America (2010), "Fifty-first supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds", The Auk 127 (3): 725–744

- Baicich, P. J.; Harrison, C. J. O. (1997), A guide to the nests, eggs, and nestlings of North American birds, San Diego, CA: Academic Press, ISBN 0120728303

- Bock, C. E.; Bock, J. H.; Grant, M. C. (1992), "Effects of Bird Predation on Grasshopper Densities in an Arizona Grassland", Ecology 73 (5): 1706–1717, doi:10.2307/1940022

- Borror, D. J. (1971), "Songs of Aimophila sparrows occurring in the United States", Wilson Bulletin 83 (2): 132–151, http://sora.unm.edu/node/128755

- Byers, C.; Curson, J.; Olsson, U. (1995), Sparrows and buntings: a guide to the sparrows and buntings of North America and the world, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co, ISBN 0395738733

- Dunning, J. B. Jr.; Bowers, R. K. Jr.; Suter, S. J.; Bock, C. E. (2000), "Cassin's Sparrow (Aimophola cassinii)", in A. Poole; F. Gill, In The Birds of North America, No. 471, Philadelphia, P.A: The Birds of North America, Inc.

- Kaufman, K. (1990), Advanced birding, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin

- Kaufman, K. (1996), Lives of North American birds, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0618159886

- Howell, S. N. G.; Webb, S. (1995), A guide to the birds of Mexico and northern Central America, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198540124

- Oberholser, H. C. (1974), The bird life of Texas, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press

- Pyle, P. (1997), Identification guide to North American birds, California: Slate Creek Press, ISBN 0961894024

- Rising, J. D. (1996), A guide to the identification and natural history of the sparrows of the United States and Canada, New York, NY: Academic Press, ISBN 0125889712

- Ruth, Janet M. (March 2000), Cassin's sparrow status assessment and conservation plan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Biological Technical Publication BTP-R6002-2000, http://digitalmedia.fws.gov/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/natdiglib&CISOPTR=6704&CISOBOX=1&REC=15, retrieved 24 March 2012

- Schnase, J. L. (1984), The breeding biology of Cassin's Sparrow in Tom Green County, Texas. Master's thesis, Angelo, TX: Angelo State University

- Schnase, J. L.; Grant, W. E.; Maxwell, T. C.; Leggett, J. J. (1991), "Time and energy budgets of Cassin's Sparrow (Aimophila cassinii) during the breeding season: evaluation through modelling", Ecological Modelling 55 (3–4): 285–319, doi:10.1016/0304-3800(91)90091-E

- Schnase, J. L.; Maxwell, T. C. (1989), "Use of song patterns to identify individual male Cassin's Sparrows", Journal of Field Ornithology 60 (1): 12–19, http://sora.unm.edu/node/51450

- Storer, R. W. (1955), "A preliminary survey of the sparrows of the genus Aimophila", Condor 57 (4): 193–201, doi:10.2307/1365082, http://sora.unm.edu/node/100717

- Terres, J. K. (1980), The Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American Birds, New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0517032880

- Williams, F. C.; LeSassier, A. L. (1968), "Cassin's Sparrow", in Oliver L. Austin, Life histories of North American cardinals, grosbeaks, buntings, towhees, finches, sparrows, and allies, New York, NY: Dover Publications, pp. 981–990

- Willoughby, E.J. (November 1986), "An Unusual Sequence of Molts and Plumages in Cassin's and Bachman's Sparrows", Condor 88 (4): 461–472, doi:10.2307/1368272, https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/condor/v088n04/p0461-p0472.pdf

- Wolf, L. L. (1977), Species relationships in the avian genus Aimophila, Ornithological Monographs, 23, Baltimore, MD: American Ornithologists' Union, pp. 1–220, http://sora.unm.edu/node/148

Further reading

- Theses

- Gordon CE. Ph.D. (1999). Community ecology and management of wintering grassland sparrows in Arizona. The University of Arizona, United States, Arizona.

- Groschupf KD. Ph.D. (1983). COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE VOCALIZATIONS AND SINGING BEHAVIOR OF FOUR AIMOPHILA SPARROWS. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, United States, Virginia.

- Kirkpatrick CK. M.S. (1999). Trends in grassland bird abundance following prescribed burning in southern Arizona. The University of Arizona, United States, Arizona.

- Articles

- Berthelsen PS & Smith LM. (1995). NONGAME BIRD NESTING ON CRP LANDS IN THE TEXAS SOUTHERN HIGH-PLAINS. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. vol 50, no 6. pp. 672–675.

- Bock CE & Bock JH. (1992). Response of Birds to Wildfire in Native Versus Exotic Arizona Grassland. Southwestern Naturalist. vol 37, no 1. pp. 73–81.

- Bock CE & Bock JH. (2002). Numerical response of grassland birds to cattle ranching versus exurban development in southeastern Arizona. Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting Abstracts. vol 87, no 79.

- Bock CE & Sharf WC. (1995). A nesting population of Cassin's Sparrows in the sandhills of Nebraska. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 65, no 4. pp. 472–475.

- Bock CE & Webb B. (1984). Birds as Grazing Indicator Species in Southeastern Arizona USA. Journal of Wildlife Management. vol 48, no 3. pp. 1045–1049.

- Deviche P, McGraw K & Greiner EC. (2005). Interspecific differences in hematozoan infection in sonoran desert Aimophila sparrows. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. vol 41, no 3. pp. 532–541.

- Dorn RD & Dorn JL. (1995). Cassin's sparrow nesting in Wyoming. Western Birds. vol 26, no 2. pp. 104–106.

- Flanders AA, Kuvlesky WP, Jr., Ruthven DC, III, Zaiglin RE, Bingham RL, Fulbright TE, Hernandez F & Brennan LA. (2006). Effects of invasive exotic grasses on South Texas rangeland breeding birds. Auk. vol 123, no 1. pp. 171–182.

- Gardner KT & Thompson DC. (1998). Influence of avian predation on a grasshopper (Orthoptera: Acrididae) assemblage that feeds on threadleaf snakeweed. Environmental Entomology. vol 27, no 1. pp. 110–116.

- Gordon CE. (2000). Movement patterns of wintering grassland sparrows in Arizona. Auk. vol 117, no 3. pp. 748–759.

- Grant DS. (1974). Cassins Sparrow Nesting in Nebraska. Nebraska Bird Review. vol 42, no 3. pp. 56–57.

- Hersey, L. J. and Rockwell R. B. (1907) "A New Breeding Bird for Colorado: The Cassin Sparrow (Peucæa cassini) Nesting near Denver" The Condor, Volume 9, No. 6 (Nov. – Dec., 1907), pages 191–194, University of California Press on behalf of the Cooper Ornithological Society

- Hubbard JP. (1977). The Status of Cassins Sparrow in New-Mexico and Adjacent States. American Birds. vol 31, no 5. pp. 933–941.

- Kingery HE & Julian PR. (1971). Cassins Sparrow Parasitized by Cowbird. Wilson Bulletin. vol 83, no 4.

- Kirkpatrick C, DeStefano S, Mannan RW & Lloyd J. (2002). Trends in abundance of grassland birds following a spring prescribed burn in southern Arizona. Southwestern Naturalist. vol 47, no 2. pp. 282–292.

- Long RC. (1968). 1st Occurrence of the Cassins Sparrow in Canada. Ontario Field Biologist. vol 22, no 34.

- Maurer BA, Webb EA & Bowers RK. (1989). Nest Characteristics and Nestling Development of Cassin's and Botteri's Sparrows in Southeastern Arizona USA. Condor. vol 91, no 3. pp. 736–738.

- Peterson AT. (2003). Subtle recent distributional shifts in Great Plains bird species. Southwestern Naturalist. vol 48, no 2. pp. 289–292.

- Ports MA. (1981). Miscellaneous Summer Records of Birds from Southwestern Kansas USA. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. vol 84, no 2. pp. 109–114.

- Savage H & Dick JA. (1969). Fowl Pox in Cassins Sparrow Aimophila-Cassinii. Condor. vol 71, no 1. pp. 71–72.

External links

- Cassin's Sparrow Nature Notes broadcast from Marfa Public Radio.

- Cassin's Sparrow BirdNote broadcast from Public Radio International's Living on Earth Environmental News Magazine.

- Cassin's Sparrow blog at CassinsSparrow.org – Long-running science blog that explores the history of Cassin's Sparrow's discovery, what we've learned about the species since, and why it matters.

Wikidata ☰ Q2229803 entry

|