Biology:Cladocera

| Cladocera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Animalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Arthropoda |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Branchiopoda |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Phyllopoda |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Cladocera Latreille, 1829 |

| Suborders | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Eucladocera (no evidence for grouping together all other cladocerans as the sister taxon to the monotypic Haplopoda (Leptodora)) | |

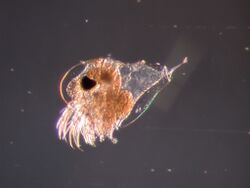

The Cladocera, commonly known as water fleas are an order of small crustaceans that feed on microscopic chunks of organic matter (excluding some predatory forms). [1]

Over 650 species have been recognised so far, with many more undescribed.[2][3][4][5] The oldest fossils of cladocerans date to the Jurassic, though their modern morphology suggests that they originated substantially earlier, during the Paleozoic. Some have also adapted to a life in the ocean, the only members of Branchiopoda to do so, even if several anostracans live in hypersaline lakes.[6] Most are 0.2–6.0 mm (0.01–0.24 in) long, with a down-turned head with a single median compound eye, and a carapace covering the apparently unsegmented thorax and abdomen. Most species show cyclical parthenogenesis, where asexual reproduction is occasionally supplemented by sexual reproduction, which produces resting eggs that allow the species to survive harsh conditions and disperse to distant habitats.

Description

They are mostly 0.2–6.0 mm (0.01–0.24 in) long, with the exception of Leptodora, which can be up to 18 mm (0.71 in) long.[7] The body is not obviously segmented and bears a folded carapace which covers the thorax and abdomen.[8]

The head is angled downwards, and may be separated from the rest of the body by a "cervical sinus" or notch.[8] It bears a single black compound eye, located on the animal's midline, in all but two genera, and often, a single ocellus is present.[9] The head also bears two pairs of antennae – the first antennae are small, unsegmented appendages, while the second antennae are large, segmented, and branched, with powerful muscles.[8] The first antennae bear olfactory setae, while the second are used for swimming by most species.[9] The pattern of setae on the second antennae is useful for identification.[8] The part of the head which projects in front of the first antennae is known as the rostrum or "beak".[8]

The mouthparts are small, and consist of an unpaired labrum, a pair of mandibles, a pair of maxillae, and an unpaired labium.[8] They are used to eat "organic detritus of all kinds" and bacteria.[8]

The thorax bears five or six pairs of lobed, leaf-like appendages, each with numerous hairs or setae.[8] Carbon dioxide is lost, and oxygen taken up, through the body surface.[8]

Lifecycle

With the exception of a few purely asexual species, the lifecycle of cladocerans is dominated by asexual reproduction, with occasional periods of sexual reproduction; this is known as cyclical parthenogenesis.[10] When conditions are favourable, reproduction occurs by parthenogenesis for several generations, producing only female clones. As the conditions deteriorate, males are produced, and sexual reproduction occurs. This results in the production of long-lasting dormant eggs. These ephippial eggs can be transported over land by wind, and hatch when they reach favourable conditions, allowing many species to have very wide – even cosmopolitan – distributions.[8]

Evolutionary history

Cladocera are nested within the clam shrimp, being most closely related to the order Cyclestherida, the only living genus of which is Cyclestheria. Though several fossils from the Paleozoic have been claimed to represent fossils of cladocerans, none of these records can be confirmed. The oldest confirmed records of cladocerans are from the Early Jurassic of Asia. Fossils from the Jurassic are assignable to modern as well as extinct groups, indicating that the intiial radiation of the group occurred prior to the beginning of the Jurassic, likely during the late Paleozoic.[11]

Ecology

Most cladoceran species live in fresh water and other inland water bodies, with only eight species being truly oceanic.[9] The marine species are all in the family Podonidae, except for the genus Penilia.[9] Some cladocerans inhabit leaf litter.[12]

Taxonomy

The superorder Cladocera is included in the class Branchiopoda, and forms a monophyletic group, which is currently divided into four orders. Around 620 species have been described, but many more species remain undescribed.[7] The genus Daphnia alone contains around 150 species.[10]

The following families are recognised:[13]

Superorder Cladocera Latreille, 1829

- Order Ctenopoda Sars, 1865

- Holopediidae Sars, 1865

- Pseudopenilidae Korovchinsky & Sergeeva, 2008

- Sididae Baird, 1850

- Order Anomopoda Stebbing, 1902

- Acantholeberidae Smirnov, 1976

- Bosminidae Baird, 1845

- Chydoridae Stebbing, 1902

- Daphniidae Straus, 1820[14]

- Dumontiidae Santos-Flores & Dodson, 2003

- Eurycercidae Kurz, 1875

- Gondwanotrichidae Van Damme et al., 2007[15][16]

- Ilyocryptidae Smirnov, 1976

- Macrotrichidae Norman & Brady, 1867

- Moinidae Goulden, 1968

- Neothricidae Dumont & Silva-Briano, 1998

- Nototrichidae Van Damme, Shiel & Dumont, 2007

- Ophryoxidae Smirnov, 1976

- Order Onychopoda Sars, 1865

- Cercopagididae Mordukhai-Boltovskoi, 1968

- Podonidae Mordukhai-Boltovskoi, 1968

- Polyphemidae Baird, 1845

- Order Haplopoda Sars, 1865

- Leptodoridae Lilljeborg, 1900

Etymology

The word "Cladocera" derives via New Latin from the Ancient Greek κλάδος (kládos, "branch") and κέρας (kéras, "horn").[17]

See also

- Bythotrephes longimanus (invasive species) [formerly known as Bythotrephes cederstroemi[18]] - Spiny Water Flea[19]

- Cercopagis pengoi (invasive species)

- Daphnia lumholtzi (invasive species)

- Moina (smallest)

- Zooplankton

References

- ↑ WoRMS (2021). Cladocera. Accessed at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1076 on 2021-05-26

- ↑ Kotov, Alexey (2007). "Jurassic Cladocera (Crustacea, Branchiopoda) with a description of an extinct Mesozoic order". Journal of Natural History 41 (1–4): 13–37. doi:10.1080/00222930601164445.

- ↑ Kotov, Alexey (2009). "New finding of Mesozoic ephippia of the Anomopoda (Crustacea: Cladocera)". Journal of Natural History 43 (9–10): 523–528. doi:10.1080/00222930802003020.

- ↑ Kotov, Alexey; Korovchinsky, Nikolai (2006). "First record of fossil Mesozoic Ctenopoda (Crustacea, Cladocera)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 146 (2): 269–274. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00204.x.

- ↑ Kotov, Alexey; Taylor, Derek (2011). "Mesozoic fossils (>145 Mya) suggest the antiquity of the subgenera of Daphnia and their coevolution with chaoborid predators". BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 129. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-129. PMID 21595889.

- ↑ Vernberg, F. John (2014). Environmental Adaptations. Elsevier Science. pp. 338–. ISBN 978-0-323-16282-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=fGF2waxot8UC&pg=PA338.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 L. Forró; N. M. Korovchinsky; A. A. Kotov; A. Petrusek (2008). "Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia 595 (1): 177–184. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5. http://decapoda.nhm.org/pdfs/27704/27704.pdf. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8259-7_19

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 Douglas Grant Smith; Kirstern Work (2001). "Cladoceran Branchiopoda (water fleas)". in Douglas Grant Smith. Pennak's Freshwater Invertebrates of the United States: Porifera to Crustacea (4th ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 453–488. ISBN 978-0-471-35837-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=GqIctb8IqPoC&pg=PA468.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Denton Belk (2007). "Branchiopoda". The Light and Smith Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon (4th ed.). University of California Press. pp. 414–417. ISBN 978-0-520-23939-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=64jgZ1CfmB8C&pg=PA416.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ellen Decaestecker; Luc De Meester; Joachim Mergaey (2009). "Cyclical parthenogeness in Daphnia: sexual versus asexual reproduction". Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis. Springer. pp. 295–316. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15. ISBN 978-90-481-2769-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=GaWD_OtE0AMC&pg=PA296.

- ↑ Van Damme, Kay; Kotov, Alexey A. (December 2016). "The fossil record of the Cladocera (Crustacea: Branchiopoda): Evidence and hypotheses" (in en). Earth-Science Reviews 163: 162–189. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.10.009. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012825216303701.

- ↑ Rubbo, Michael J.; Kiesecker, Joseph M. (2004). "Leaf litter composition and community structure: translating regional species changes into local dynamics". Ecology 85 (9): 2519–2525. doi:10.1890/03-0653.

- ↑ Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132. http://atiniui.nhm.org/pdfs/3839/3839.pdf.

- ↑ Norambuena, Juan-Alejandro; Farías, Jorge; De los Ríos, Patricio (2019-12-05). "The water flea Daphnia pulex (Cladocera, Daphniidae), a possible model organism to evaluate aspects of freshwater ecosystems". Crustaceana 92 (11-12): 1415–1426. doi:10.1163/15685403-00003948. ISSN 0011-216X. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685403-00003948.

- ↑ K. Van Damme; R. J. Shiel; H. J. Dumont (2007). "Notothrix halsei gen. n., sp. n., representative of a new family of freshwater cladocerans (Branchiopoda, Anomopoda) from SW Australia, with a discussion of ancestral traits and a preliminary molecular phylogeny of the order". Zoologica Scripta 36 (5): 465–487. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2007.00292.x.

- ↑ K. Van Damme; R. J. Shiel; H. J. Dumont (2007). "Gondwanotrichidae nom. nov. pro Nototrichidae Van Damme, Shiel & Dumont, 2007". Zoologica Scripta 36 (5): 623. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2007.00304.x.

- ↑ "Webster's II New College Dictionary". Webster's II New College Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-618-39601-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=OL60E3r2yiYC&pg=PA211.

- ↑ USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species: Bythotrephes longimanus

- ↑ (April 16, 2013) NorthAmericanFishing - "Silent Invaders" Spiny Water Flea PT 1 2013

- Brusca, R.C.; Brusca, G.J. (1990). Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA (USA). ISBN 0-87893-098-1. 922 pp

- Martin, J.W., & Davis, G.E. (2001). An updated classification of the recent Crustacea. Science Series, 39. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Los Angeles, CA (USA). 124 pp.

- Norambuena, J., J. Farías & P. De los Ríos. (2019). he water flea Daphnia pulex (Cladocera, Daphniidae), a possible model organism to evaluate aspects of freshwater ecosystems. Crustaceana, (11-12): 1415-1426.

External links

- Cladocera – Guide to the Marine Zooplankton of South Eastern Australia

Wikidata ☰ Q391240 entry