Biology:Crithidia

| Crithidia | |

|---|---|

| |

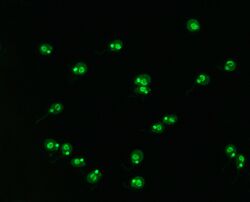

| Crithidia luciliae (immunofluorescence pattern). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Euglenozoa |

| Class: | Kinetoplastea |

| Order: | Trypanosomatida |

| Family: | Trypanosomatidae |

| Genus: | Crithidia Léger, 1902[1] |

| Species | |

| |

Crithidia is a genus of trypanosomatid Euglenozoa. They are parasites that exclusively parasitise arthropods, mainly insects. They pass from host to host as cysts in infective faeces and typically, the parasites develop in the digestive tracts of insects and interact with the intestinal epithelium using their flagellum. They display very low host-specificity and a single parasite can infect a large range of invertebrate hosts.[3] At different points in its life-cycle, it passes through amastigote, promastigote, and epimastigote phases; the last is particularly characteristic, and similar stages in other trypanosomes are often called crithidial.

The etymology of the genus name Crithidia derives from the Ancient Greek word κριθίδιον (krithídion), meaning "small grain of barley".[4][5]

Species

- Crithidia bombi is a well documented species, notable for being a parasite of various bumblebee species, including common species like Bombus terrestris, Bombus muscorum, and Bombus hortorum.[6][7]

- Crithidia mellificae is a parasite of the bee.

- Crithidia brevicula might incorporate species of the genus Wallaceina (Wallaceina brevicula, W. inconstans, W. vicina, and W. podlipaevi) as suggested by molecular phylogenies based on 18S ribosomal RNA and glycosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase sequences.[8]

- Other species include C. fasciculata, C. guilhermei and C. luciliae.

- C. luciliae is the substrate for the antinuclear antibody test used to diagnose lupus and other autoimmune disorders

Impact on bumble bees

These parasites may be at least partially responsible for declining wild bumble bee populations. They cause the bumble bees to lose their ability to distinguish between flowers that contain nectar and those that don't. They make many mistakes by visiting nectar scarce flowers and in so doing, slowly starve to death. Commercially bred bumble bees are used in greenhouses to pollinate plants, for example tomatoes, and these bumble bees typically harbor the parasite, while wild bumble bees do not. It is believed that the commercial bumble bees transmitted the parasite to wild populations in some cases. They escape from the greenhouses through vents; a simple mesh could help prevent this.[9]

Bibliography

- ↑ Léger, Louis. 1902. Sur un flagellé parasite de l'Anopheles maculipennis. Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol., 54: 354-356, [1].

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 "Crithidia - Overview - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org. http://eol.org/pages/2910547/overview.

- ↑ Boulanger (2001). "Immune response of Drosophila melanogaster to infection of the flagellate parasite Crithidia spp.". Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 31 (2): 129–37. doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00096-5. PMID 11164335.

- ↑ Bailly, Anatole (1981-01-01). Abrégé du dictionnaire grec français. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-2010035289. OCLC 461974285.

- ↑ Bailly, Anatole. "Greek-french dictionary online". http://www.tabularium.be/bailly/.

- ↑ Runckel, Charles; DeRisi, Joseph; Flenniken, Michelle L. (2014-04-17). "A Draft Genome of the Honey Bee Trypanosomatid Parasite Crithidia mellificae". PLOS ONE 9 (4): e95057. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095057. PMID 24743507. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...995057R.

- ↑ Baer, B. and P. Schmid-Hempel (2001). "Unexpected consequences of polyandry for parasitism and fitness in the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris". Evolution 55 (8): 1639–1643. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[1639:ucopfp2.0.co;2]. PMID 11580023.

- ↑ Kostygov, Alexei Yu.; Grybchuk-Ieremenko, Anastasiia; Malysheva, Marina N.; Frolov, Alexander O.; Yurchenko, Vyacheslav (2014-09-01). "Molecular revision of the genus Wallaceina" (in en). Protist 165 (5): 594–604. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2014.07.001. ISSN 1434-4610. PMID 25113831. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1434461014000662.

- ↑ Colla, Sheila R.; Otterstatter, Michael C.; Gegear, Robert J.; Thomson, James D. (2006-05-01). "Plight of the bumble bee: Pathogen spillover from commercial to wild populations". Biological Conservation 129 (4): 461–467. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.013.

Further reading

E Riddell, Carolyn; D Lobaton Garces, Juan; Adams, Sally (27 November 2014). "Differential gene expression and alternative splicing in insect immune specificity". BMC Genomics 15 (1): 1031. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-1031. PMID 25431190. ![]()

Otterstatter, Michael C.; Thomson, James D. (23 July 2008). "Does Pathogen Spillover from Commercially Reared Bumble Bees Threaten Wild Pollinators?". PLOS ONE 3 (7): e2771. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002771. PMID 18648661. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.2771O. ![]()

Daniel, Cariveau; Elijah, Powell; Hauke, Koch (April 2014). "Variation in gut microbial communities and its association with pathogen infection in wild bumble bees (Bombus)". The ISME Journal 8 (12): 2369–2379. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.68. PMID 24763369.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1998692 entry

|