Biology:Equisetum similkamense

| Equisetum similkamense | |

|---|---|

| |

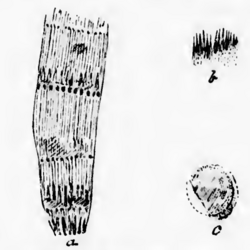

| Equisetum similkamense from Dawson 1890 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Polypodiophyta |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida |

| Subclass: | Equisetidae |

| Order: | Equisetales |

| Family: | Equisetaceae |

| Genus: | Equisetum |

| Species: | †E. similkamense

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Equisetum similkamense Dawson

| |

Equisetum similkamense is an extinct horsetail species in the family Equisetaceae described from a group of whole plant fossils including rhizomes, stems, and leaves. The species is known from Ypresian sediments exposed in British Columbia, Canada. It is one of several extinct species placed in the living genus Equisetum.

History and classification

Fossils of Equisetum similkamense were collected during field work in 1877 from outcrops of the Allenby Formation along Nine Mile Creek near Princeton. These were examined and described by John William Dawson (1879) as a new species based on stems, leaves, and rhizomes. Dawson did not give an etymology for the species name in the type description, though the type locality of Nine Mile Creek is a tributary of Whipsaw Creek, a tributary in turn of the Similkameen River.[1] Dawson (1890) reprinted his description of the species with some elaboration of the details and included drawn illustrations of representative fossils.[2]

Dawson (1879) notes E. similkamense to be most similar to varieties of the Miocene species Equisetum winkleri from Tjörnes, Iceland and Equisetum limosellum from Öhningen, Germany. Dawson (1890) also suggested the possibility of Equisetum globulosum, described by Lesquereux from Paleocene Alaskan fossils, might be of the same species. However Dawson cited the incomplete nature of the Alaskan fossils and the more globose nature of the rhizomes there as reason not to make a firm comparison.[2]

Distribution and paleoecology

Equisetum similkamense is known from a series of specimens which were recovered from a single formation in the Eocene Okanagan Highlands, outcrops of the Ypresian[3] Allenby Formation around Princeton, British Columbia.[4] In addition to the type locality on Nine Mile Creek, an additional find of E. similkamense was reported by Melcon (1975) from outcrops of brecciated shale near Glacier Lake in Cathedral Provincial Park.[5] The Allenby Formation preserves an upland lake system surrounded by a mixed conifer–broadleaf forest with nearby volcanism.[6] The highlands likely had a mesic upper microthermal to lower mesothermal climate, in which winter temperatures rarely dropped low enough for snow, and which were seasonably equitable.[7] The Okanagan Highlands paleoforest surrounding the lakes have been described as precursors to the modern temperate broadleaf and mixed forests of Eastern North America and Eastern Asia. Based on the fossil biotas the lakes were higher and cooler than the coeval coastal forests preserved in the Puget Group and Chuckanut Formation of Western Washington, which are described as lowland tropical forest ecosystems. Estimates of the paleoelevation range between 0.7–1.2 km (0.43–0.75 mi) higher than the coastal forests. This is consistent with the paleoelevation estimates for the lake systems, which range between 1.1–2.9 km (1,100–2,900 m), which is similar to the modern elevation 0.8 km (0.50 mi), but higher.[7]

Estimates of the mean annual temperature for the Allenby Formation have been derived from climate leaf analysis multivariate program (CLAMP) analysis and leaf margin analysis (LMA) of the Princeton paleoflora. The CLAMP results after multiple linear regressions for Princeton gave a mean annual temperature of approximately 5.1 °C (41.2 °F), while the LMA gave 5.1 ± 2.2 °C (41.2 ± 4.0 °F). This is lower than the mean annual temperature estimates given for the coastal Puget Group, which is estimated to have been between 15–18.6 °C (59.0–65.5 °F). The bioclimatic analysis for Princeton suggests mean annual precipitation amounts of 114 ± 42 cm (45 ± 17 in).[7]

Equisetum genus fossils have been reported from the coeval Chu Chua Formation, the Tranquille formation and Klondike Mountain Formation, but none of these occurrences have been described to species.[8][9][10]

Description

The stems of Equisetum similkamense have an average diameter of 15 mm (0.6 in) though some exceed that, most of which are missing leaves. The stem walls are thin with larger stems having up to sixty vertically running ribs. The nodes of the stems can be placed as close as 1 cm (0.4 in), but typically are much further apart. The nodes are accompanied by sheaths approximately 6 mm (0.24 in) long with up to thirty-five teeth. The sheath teeth vary from short with an obtuse tip to long and tapered with sharp tips, though they uniformly have a single vein per tooth.[1] The rhizomes are smooth to faintly striated sporting round to ovoid tubercles, and with slender branching rootlets.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dawson, J. W. (1879). "Appendix B. List of tertiary plants in the southern part of British Columbia, with the description of a new species of Equisetum". Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for. 1877-1878. Montreal, Quebec: Dawson Brothers. pp. 187. https://books.google.com/books?id=ELcEAAAAQAAJ.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dawson, J. W. (1890). On fossil plants from the Similkameen Valley and other places in the southern interior of British Columbia.. Royal Society of Canada.

- ↑ Moss, P. T.; Greenwood, D. R.; Archibald, S. B. (2005). "Regional and local vegetation community dynamics of the Eocene Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia – Washington State) from palynology". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 42 (2): 187–204. doi:10.1139/E04-095. Bibcode: 2005CaJES..42..187M.

- ↑ Wolfe, J.A.; Tanai, T. (1987). "Systematics, Phylogeny, and Distribution of Acer (maples) in the Cenozoic of Western North America". Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University. Series 4, Geology and Mineralogy 22 (1): 1–246. http://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/handle/2115/36747?mode=full&submit_simple=Show+full+item+record.

- ↑ Melcon, P. Z. (1975), "Physiography:Tertiary", Tors and weathering on McKeen Ridge, Cathedral Provincial Park, British Columbia, Simon Fraser University. Theses (Dept. of Geography), pp. 31–33

- ↑ Archibald, S.; Greenwood, D.; Smith, R.; Mathewes, R.; Basinger, J. (2011). "Great Canadian Lagerstätten 1. Early Eocene Lagerstätten of the Okanagan Highlands (British Columbia and Washington State)". Geoscience Canada 38 (4): 155–164.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Greenwood, D.R.; Archibald, S.B.; Mathewes, R.W; Moss, P.T. (2005). "Fossil biotas from the Okanagan Highlands, southern British Columbia and northeastern Washington State: climates and ecosystems across an Eocene landscape". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 42 (2): 167–185. doi:10.1139/e04-100. Bibcode: 2005CaJES..42..167G.

- ↑ Greenwood, David R.; Pigg, Kathleen B.; Basinger, James F.; DeVore, Melanie L. (2015). "A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences: 15, 18–19.

- ↑ Wilson, M.V.H. 2009. McAbee Fossil Site Assessment Report. 60 pp.Online PDF. Accessed 17 May 2021.

- ↑ Joseph, N. L. (1988). "Important Eocene Flora and Fauna Unearthed at Republic, Washington". Rocks & Minerals 63 (2): 146–151. doi:10.1080/00357529.1988.11761830. Bibcode: 1988RoMin..63..146J.

Wikidata ☰ Q106946684 entry

|