Biology:Ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium

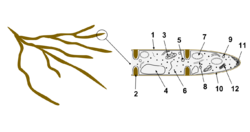

Ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium (also known as extraradical mycelium) is the collection of filamentous fungal hyphae emanating from ectomycorrhizas. It may be composed of fine, hydrophilic hypha which branches frequently to explore and exploit the soil matrix or may aggregate to form rhizomorphs; highly differentiated, hydrophobic, enduring, transport structures.

Characteristics

Overview

Apart from mycorrhizas, extramatrical mycelium is the primary vegetative body of ectomycorrhizal fungi. It is the location of mineral acquisition,[1] enzyme production,[2] and a key means of colonizing new root tips.[3] Extramatrical mycelium facilitates the movement of carbon into the rhizosphere,[4] moves carbon and nutrients between hosts [5] and is an important food source for invertebrates.[6]

Exploration type

The mycelial growth pattern, extent of biomass accumulation, and the presence or absence of rhizomorphs are used to classify fungi by exploration type. Agerer first proposed the designation of exploration types in 2001,[7] and the concept has since been widely employed in studies of ectomycorrhizal ecology. Four exploration types are commonly recognized: Contact, Short-distance, Medium-distance and Long-distance.

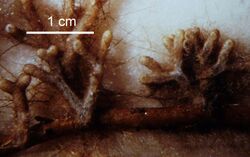

Contact exploration types possess a predominantly smooth mantle and lack rhizomorphs with ectomycorrhizas in close contact with the surrounding substrate. Short-distance exploration types also lack rhizomorphs but the mantle is surrounded by frequent projections of hyphae, which emanate a short distance into the surrounding substrate. Most ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes are included in this group.

Medium-distance exploration types are further divided into three subtypes defined by the growth range and differentiation of its rhizomorphs. Medium-distance Fringe form interconnected hyphal networks with rhizomorphs that divide and fuse repeatedly. Medium-distance Mat types form dense hyphal mats which aggregate into a homogeneous mass. Finally, the Medium-distance Smooth sub-type has rhizomorphs with smooth mantles and margins.

Long-distance exploration types are highly differentiated, forming rhizomorphs that contain hollow vessel-like transport tubes. Long distance types are associated with increased levels of organic nitrogen uptake compared to other exploration types and are thought to be less competitive in disturbed systems in contrast to short distance types which are able to regenerate more efficiently after a disturbance event.[8]

Exploration type is primarily consistent within a given lineage. However, some fungal genera which contain a large number of species have a great diversity of extramatrical hyphal morphology and are known to contain more than one exploration type.[9] Because of this, extrapolating exploration type to species known only by lineage is difficult.[10] Often, fungi fail to fit into a defined exploration type, falling instead along a gradient. Exploration type also fails to take into account other aspects of hyphal morphology, such as the extent to which hyphae cross into deeper soil horizons.[11]

Field studies have shown that extramatrical mycelium is more likely to proliferate in mineral soils than in organic material, and may be particularly absent in fresh leaf litter.[12] However, the presence of different ectomycorrhizal groups in different soil horizons suggest that different groups have evolved specialized niche separation, possibly attributable to exploration type.[13]

Ecological implications

Community assembly

Because ectomycorrhizas are small and possess a limited contact area with the surrounding soil, the presence of extramatrical hyphae significantly increases the surface area in contact with the surrounding environment. Increased surface area means greater access to necessary nutrient sources. Additionally, the presence of rhizomorphs or mycelial cords, can act comparably to xylem tissue in plants, where hollow tubes of vessel hyphae shuttle water and solubilized nutrients over long distances.[14] The abundance and spatial distribution of host root tips in the rhizosphere is an important factor mediating ectomycorrhizal community assembly. Root density may select for the exploration types best suited for a given root spacing. In Pine systems, Fungi that display short-distance exploration types are less able to colonize new roots spaced far from the mycorrhiza, and long-distance types dominate areas of low root density. Conversely, short-distance exploration types tend to dominate areas of high root density where decreased carbon expenditure makes them more competitive than long-distance species.[15] The growth of extramatrical mycelium has a direct effect on the mutualistic nutrient trading between ectomycorrhizal fungi and their hosts. Increased hyphal occupation of the soil allows the fungus to take greater advantage of water and nutrients otherwise inaccessible to plant roots and to more efficiently transport these resources back to the plant. Conversely, the increased costs in carbon allocation associated with supporting a fungal partner with an extensive mycelial system presents a number of questions related to the costs and benefits of ectomycorrhizal mutualism.[16]

Carbon cycling

Although there is evidence that certain species of mycorrhizal fungi may obtain at least a portion of their carbon via saprotrophic nutrition,[17] the bulk of mycorrhizal carbon acquisition happens by way of trading for host-derived photosynthetic products. Mycorrhizal systems represent a major carbon sink. Laboratory studies predict that around 23% of plant-derived carbon is allocated to extrametrical mycelium,[18] although an estimated 15-30% of this is lost to fungal respiration.[19][20] Carbon allocation is distributed unequally to extramatrical mycelium depending on fungal taxa, nutrient availability, and the age of the associated mycorrhizas.[21][22] Much of the carbon allocated to extramatrical mycelium accumulates as fungal biomass, making up an estimated one-third of the total microbial biomass and one-half of the total dissolved organic carbon in some forest soils.[4] Carbon also supports the production of sporocarps and sclerotia, with various taxa investing differentially in these structures rather than in the proliferation of extramatrical mycelium. Carbon acquisition also goes toward the production of fungal exudates. Extramatrical hyphae excrete a range of compounds into the soil matrix, accounting for as much as 40% of total carbon usage.[23] These exudates are released primarily at the growing front, and are used in functions such as mineralization and homeostasis.[24]

Many researchers have attempted projections of the role that extramatrical mycelium may play in carbon sequestration. Although estimates of the life span of individual ectomycorrhizas very considerably, turnover is generally considered on a scale of months.

After death, the presence ectomycorrhizas on root tips, may increase the rate of root decomposition for some fungal taxa.[25] Besides host plant death and mycorrhizal turnover, rates of carbon sequestration may also be affected by disturbances in the soil, which cause sections of the extramatrical mycelium to become severed from the host plant. Such disturbances, such as those caused by animal disruption, mycophagous invertebrates or habitat destruction, may have a notable impact on turnover rates. These variables make it difficult to estimate the turnover rates of mycorrhizal biomass in forest soils and the relative contribution of extramatrical mycelium to carbon sequestration.

Mycelial networks

The presence of long-distance extramatrical hyphae may affect forest health via the formation of common mycelial networks, in which hyphal connections form between plant hosts and can facilitate the transfer of carbon and nutrients between hosts.[26] Mycelial networks may also be responsible for facilitating the transport of allelopathic chemicals from the supplying plant directly to the rhizosphere of other plants.[27] Ectomycorrhizal fungi increase primary production in host plants, with multi trophic effects. In this way, extramatrical mycelium is important to the maintenance of soil food webs,[6] supplying a significant nutritive source to invertebrates and microorganisms.

Mineral access

Enzyme production

The enzymatic activities of ectomycorrhizal fungi are highly variable between species. These differences are correlated with exploration type (particularly the presence or absence of rhizomorphs) rather than lineage or host association- suggesting that similar morphologies of extraradical mycelium are an example of convergent evolution.[2] Differences in enzymatic activity, and hence the ability to degrade organic compounds dictate fungal nutrient access, with wide-ranging ecological implications.

Phosphorus

Because diverse ectomycorrhizal fungal taxa differ greatly in their metabolic activity[28] they also often differ in their capacity to trade nutrients with their hosts.[29] Phosphorus acquisition by mycorrhizal fungi, and the subsequent transfer to plant hosts, is thought to be one of the main functions of ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. Extramatrical mycelium is the site of collection for phosphorus within the soil system. This relationship is so strong that starving host plants of phosphorus is known to increase the growth of extramatrical mycelium tenfold.[30]

Nitrogen

Recently, Isotopic studies have been used to investigate relative trading between ectomycorrhizal fungi and plant hosts and to assess the relative importance of exploration type on nutrient trading ability. 15N values are elevated in ectomycorrhizal Fungi and depleted in fungal hosts, as a result of nutrient trading.[31] Fungal species with exploration types producing greater amounts of extraradical mycelium are known to accumulate greater amounts 15N [2][32] in both root tips and fruit bodies, a phenomenon partially attributed to higher levels of N cycling within these species.

Assessment methods

Determining the longevity of extramatrical mycelium is difficult, and estimates range from just a few months to several years. Turnover rates are assessed in a variety of ways including direct observation and 14C dating. Such estimates are an important variable in calculating the contribution that ectomycorrhizal fungi have to carbon sequestration.[33] In order to differentiate ectomycorrhizal mycelium from the mycelium of saprotrophic fungi, biomass estimates are often done by ergosterol or phospholipid fatty acid analysis, or by using sand-filled bags, which are likely to be avoided by saprotrophic fungi because they lack organic matter.[33] Detailed morphological characterization of exploration type has been defined for over 550 different ectomycorrhizal species and are compiled in www. deemy. de. Due to the difficulty in classifying exploration types of intermediate forms, other metrics have been proposed to qualify and quantify the growth of extramatrical mycelium, including Specific Actual/Potential Mycelium Space Occupation and Specific Extramatrical Mycelial Length[34] which attempt to account for the contributions of mycelial density, surface area and total biomass.

References

- ↑ "Linking plants to rocks: ectomycorrhizal fungi mobilize nutrients from minerals.". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 16 (5): 248–254. 2001. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02122-X. PMID 11301154.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tedersoo, Leho; Naadel, Triin; Bahram, Mohammad; Pritsch, Karin; Buegger, Franz; Leal, Miguel; Kõljalg, Urmas; Põldmaa, Kadri (2012). "Enzymatic activities and stable isotope patterns of ectomycorrhizal fungi in relation to phylogeny and exploration types in an afrotropical rain forest". New Phytologist 195 (4): 832–843. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04217.x. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 22758212.

- ↑ Anderson, I.C.; Cairney, J. W. G. (2007). "Ectomycorrhizal fungi: exploring the mycelial frontier.". FEMS Microbiology Reviews 31 (4): 388–406. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00073.x. PMID 17466031.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Högberg, M.N.; Högberg, P. (2002). "Extramatrical ectomycorrhizal mycelium contributes one-third of microbial biomass and produces, together with associated roots, half the dissolved organic carbon in a forest soil.". New Phytologist 154 (3): 791–795. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00417.x. PMID 33873454.

- ↑ Selosse, M.A.; Richard, F.; He, X.; Simard, S. W. (2006). "Mycorrhizal networks: des liaisons dangereuses?". Ecology and Evolution 21 (11): 621–8. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.003. PMID 16843567.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Pollierer, M.M.; Langel, R.; Körner, C.; Maraun, M.; Scheu, S. (2007). "The underestimated importance of belowground carbon input for forest soil animal food webs.". Ecology Letters 10 (8): 729–36. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01064.x. PMID 17594428.

- ↑ Agerer, R. (2001). "Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae A proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance". Mycorrhiza 11 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1007/s005720100108.

- ↑ Lilleskov, E. A; Hobbie, E. A.; Horton, T. R. (2011). "Conservation of ectomycorrhizal fungi: exploring the linkages between functional and taxonomic responses to anthropogenic N deposition". Fungal Ecology 4 (2): 174–183. doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2010.09.008.

- ↑ Agerer, R. (2006). "Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae". Mycological Progress 5 (2): 67–107. doi:10.1007/s11557-006-0505-x.

- ↑ Tedersoo, L.; Smith, M. E (2013). "Lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi revisited: Foraging strategies and novel lineages revealed by sequences from belowground.". Fungal Biology Reviews 27 (3–4): 83–99. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2013.09.001.

- ↑ Genney, D.R.; Anderson, I. C.; Alexander, I. J. (2006). "Fine-scale distribution of pine ectomycorrhizas and their extramatrical mycelium.". The New Phytologist 170 (2): 381–90. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01669.x. PMID 16608462.

- ↑ Lindahl, B.D.; Ihrmark, K.; Boberg, J.; Trumbore, S. E.; Högberg, P.; Stenlid, J.; Finlay, R. D. (2007). "Spatial separation of litter decomposition and mycorrhizal nitrogen uptake in a boreal forest.". New Phytologist 173 (3): 611–20. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01936.x. PMID 17244056. https://escholarship.org/content/qt1r43h5sj/qt1r43h5sj.pdf?t=oemmul.

- ↑ Landeweert, R.; Leeflang, P.; Kuyper, T. W.; Hoffland, E.; Rosling, A.; Wernars, K.; Smit, E. (2003). "Molecular identification of ectomycorrhizal mycelium in soil horizons.". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 69 (1): 327–33. doi:10.1128/aem.69.1.327-333.2003. PMID 12514012. Bibcode: 2003ApEnM..69..327L.

- ↑ Cairney, J. W. G. (1992). "Translocation of solutes in ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic rhizomorphs.". Mycological Research 96 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80928-3.

- ↑ Peay, K. G; Kennedy, P. G.; Bruns, T. D. (2011). "Rethinking ectomycorrhizal succession: are root density and hyphal exploration types drivers of spatial and temporal zonation?". Fungal Ecology 4 (3): 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2010.09.010.

- ↑ Weigt, R. B.; Raidl, S.; Verma, R.; Agerer, R. (2011). "Exploration type-specific standard values of extramatrical mycelium – a step towards quantifying ectomycorrhizal space occupation and biomass in natural soil.". Mycological Progress 11 (1): 287–297. doi:10.1007/s11557-011-0750-5.

- ↑ Talbot, J.M.; Allison, S. D.; Treseder, K. K. (2008). "Decomposers in disguise: mycorrhizal fungi as regulators of soil C dynamics in ecosystems under global change.". Functional Ecology 22 (6): 955–963. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01402.x. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5nz5166p.

- ↑ Rygiewicz, P.T.; Andersen, C. P. (1994). "Mycorrhizae alter quality and quantity of carbon allocated below ground.". Nature 369 (6475): 58–60. doi:10.1038/369058a0. Bibcode: 1994Natur.369...58R. https://zenodo.org/record/1233159.

- ↑ Hasselquist, N.J.; Vargas, R.; Allen, M. F. (2009). "Using soil sensing technology to examine interactions and controls between ectomycorrhizal growth and environmental factors on soil CO2 dynamics.". Plant and Soil 331 (1–2): 17–29. doi:10.1007/s11104-009-0183-y.

- ↑ Heinemeyer, Andreas; Hartley, Iain P.; Evans, Sam P.; Carreira De La Fuente, José A.; Ineson, Phil (2007). "Forest soil CO2flux: uncovering the contribution and environmental responses of ectomycorrhizas". Global Change Biology 13 (8): 1786–1797. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01383.x. ISSN 1354-1013. Bibcode: 2007GCBio..13.1786H.

- ↑ Rosling, A.; Lindahl, B. D.; Finlay, R. D. (2004). "Carbon allocation to ectomycorrhizal roots and mycelium colonising different mineral substrates.". New Phytologist 162 (3): 795–802. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01080.x. PMID 33873765.

- ↑ Wu, B.; Nara, K.; Hogetsu, T. (2002). "Spatiotemporal transfer of carbon-14-labelled photosynthate from ectomycorrhizal Pinus densiflora seedlings to extraradical mycelia.". Mycorrhiza 12 (2): 83–88. doi:10.1007/s00572-001-0157-2. PMID 12035731.

- ↑ Fransson, P.M.A.; Anderson, I. C.; Alexander, I. J. (2007). "Ectomycorrhizal fungi in culture respond differently to increased carbon availability.". Microbiology Ecology 61 (1): 246–57. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00343.x. PMID 17578526.

- ↑ Sun, Y.P.; Unestam, T.; Lucas, S. D.; Johanson, K. J.; Kenne, L.; Finlay, R. (1999). "Exudation-reabsorption in a mycorrhizal fungus, the dynamic interface for interaction with soil and soil microorganisms.". Mycorrhiza 9 (3): 137–144. doi:10.1007/s005720050298.

- ↑ Koide, R.T.; Fernandez, C. W.; Peoples, M. S. (2011). "Can ectomycorrhizal colonization of Pinus resinosa roots affect their decomposition?". New Phytologist 191 (2): 508–14. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03694.x. PMID 21418224.

- ↑ Selosse, M.A.; Richard, F.; He, X.; Simard, S. W. (2006). "Mycorrhizal networks: des liaisons dangereuses?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 21 (11): 621–8. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.003. PMID 16843567.

- ↑ Barto, E.K.; Hilker, M.; Müller, F.; Mohney, B. K.; Weidenhamer, J. D.; Rillig, M. C. (2011). "The fungal fast lane: common mycorrhizal networks extend bioactive zones of allelochemicals in soils.". PLOS ONE 6 (11): e27195. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027195. PMID 22110615. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...627195B.

- ↑ Trocha, L. K., L. K.; Mucha, J.; Eissenstat, D. M.; Reich, P. B.; Oleksyn, J. (2010). "Ectomycorrhizal identity determines respiration and concentrations of nitrogen and non-structural carbohydrates in root tips: a test using Pinus sylvestris and Quercus robur saplings.". Tree Physiology 30 (5): 648–54. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpq014. PMID 20304781.

- ↑ Burgess, T. I.; Malajczuk, N.; Grove, T. S. (1993). "The ability of 16 ectomycorrhizal fungi to increase growth and phosphorus uptake of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. and E. diversicolor F. Muell.". Plant and Soil 153 (2): 155–164. doi:10.1007/BF00012988. http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/3244/.

- ↑ Wallander, H.; Nylund, J. E. (1992). "Effects of excess nitrogen and phosphorus starvation on the extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizas of Pinus sylvestris L.". New Phytologist 120 (4): 495–503. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1992.tb01798.x.

- ↑ Hogberg, P.; Hogberg, M. N.; Quist, M. E.; Ekblad, A.; Nasholm, T. (1999). "Nitrogen isotope fractionation during nitrogen uptake by ectomycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal Pinus sylvestris.". New Phytologist 142 (3): 569–576. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00404.x.

- ↑ Hobbie, E.A.; Agerer, R. (2009). "Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types". Plant and Soil 327 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1007/s11104-009-0032-z.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Cairney, J. W. G (2012). "Extramatrical mycelia of ectomycorrhizal fungi as moderators of carbon dynamics in forest soil.". Soil Biology and Biochemistry 47: 198–208. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.12.029.

- ↑ Weigt, R.B.; Raidl, S.; Verma, R.; Agerer, R. (2011). "Exploration type-specific standard values of extramatrical mycelium – a step towards quantifying ectomycorrhizal space occupation and biomass in natural soil.". Mycological Progress 11 (1): 287–297. doi:10.1007/s11557-011-0750-5.

|