Biology:Gammarus desperatus

| Gammarus desperatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| G. desperatus in Chaves County, New Mexico, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Peracarida |

| Order: | Amphipoda |

| Family: | Gammaridae |

| Genus: | Gammarus |

| Species: | G. desperatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gammarus desperatus Cole, 1981

| |

Gammarus desperatus, commonly known as Noel's Amphipod, is a species of small, amphipod crustacean in the family Gammaridae.

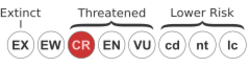

Noel's Amphipod was formerly found at three sites in New Mexico, but it has since been extirpated from two of these sites.[1] Noel's Amphipod only survives within Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge.[1] It is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List,[1] and as an endangered species under the United States Endangered Species Act.[2]

Description

Noel's Amphipods are small aquatic invertebrates found in freshwater. Noel's amphipods are a brownish-green color, with kidney-shaped eyes and red stripes running along numerous different segments.[3] They have two sets of antennae that are covered in setae, which are hair-like structures found on many invertebrates.[4] Noel's Amphipod is also known to have 5-7 spines located near the head.[5] Males are somewhat bigger than females, with sizes ranging from 8.5 to 14.8 millimeters.[3]

Life history

Noel's amphipods complete a full life cycle in one year. Due to the short life span of the species, individuals have a fast growth rate and reach sexual maturity usually within two months. The breeding times range from February to October depending on water temperatures.[3] When a male and female amphipod come together to mate, the male grasps the female with its gnathopods and guards her for up to seven days to defend against potential rival males.[6] During this period of mate-guarding, the pair continue to feed and swim until the female molts.[3] Shortly after molting, the female releases the eggs into the marsupium (egg pouch), and the male then fertilizes the eggs. The female incubates the eggs in the egg pouch until the young hatch, then releases them after a few hours or days.[6] The Noel's amphipod produces a brood of 15 to 50 young amphipods.[3]

Ecology

Diet

Noel's amphipods are omnivorous and feed on algae, underwater vegetation and decaying matter. They often are seen feeding on biofilms that form on submerged aquatic vegetation; these biofilms consist of algae, diatoms, bacteria, and fungi. Microbial foods associated with periphyton or aquatic plants, such as algae and bacteria, are essential for juvenile amphipods.[7]

Behavior

Noel's amphipods exhibit a period of mate-guarding in which the male is territorial over the female and protects his mate from other males that compete for the ability to fertilize the female's eggs.[6] This species is mostly nocturnal due to its sensitivity to light, and is mostly active only during the nighttime.[3]

Habitat

The amphipods require clean, shallow, cool, and permanently flowing well-oxygenated waters of streams, ponds, ditches, sloughs, and springs.[6][3] In addition to this, this species is very sensitive to pH changes in the water, and also requires high levels of calcium for survival.[6] These amphipods are often found underneath stones and amongst submerged aquatic vegetation. They are extremely sensitive to water contamination and do not tolerate habitat desiccation, standing water or sedimentation.[3] In summary, this species is very sensitive to habitat degradation.

Range

Noel's amphipod was formerly found at three sites in New Mexico, but it has since been eradicated from two of these sites.[1] Noel's amphipod only survives within Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge at the Sago Spring Wetland Complex, Bitter Creek, and along the western boundary of Unit 6.[6]

Conservation

Population size

In the past, amphipod populations have been able to reach extremely high densities, occasionally exceeding 10,000 per square meter. In 1954, Noel's amphipod was described as the largest population of macro-invertebrates at Lander Springbrook, with densities ranging from 2,338 to 10,416 per square meter. In 1995 and 1996, on Bitter Lake National Wildlife refuge the Noel's amphipod population density ranged from 64 per square meter to 8,768 per square meter at Bitter Creek and 20 per square meter to 575 per square meter at Sago Spring Wetland Complex. In 1999, the population density of the Noel's amphipod at Unit 6 on Bitter Lake National Wildlife refuge was 344 per square meter.[6]

Major threats

One key threat to the Noel's amphipod is diminished water quantity in the area due to groundwater pumping and drought. Water contamination also affects these amphipods. Secondary threats to these organisms include inadequate existing regulatory mechanisms, localized range, limited mobility, fragmented habitat, and climate change.[6]

Past and current geographical distribution

Noel's amphipod was originally found in three springs near the Roswell Basin in New Mexico, but both populations outside of Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge vanished before 1988 due to groundwater depletion and spring channelization. A 2002 fire destroyed their population within the refuge by removing the vegetative cover that protected them from sunlight and depositing ash and debris into their freshwater habitat.[6] It is currently assumed that they are now only found within the Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge.[8]

Date listed

The Noel's Amphipod was listed on the Endangered Species Act on August 9, 2005, because of its small population that appears to only exist in the Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico.[8]

Five-year review

In 2020, a five-year review was conducted on four endangered species in the Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge, including the Noel's Amphipod. In 2010, the initial 5-year review of these species was completed and Critical Habitat designation was finalized in June 2011. Critical habitat designation was achieved in June 2011. In the critical habitat designation, 70.2 acres were given to the Noel's Amphipod. The Final Recovery Plan for these four invertebrate species was finalized in October 2019 and makes references to the five-year review.[9] In this five-year review, there are four goals listed. The first goal is to maintain the long term survival of each species, the second is to protect water quantity, the third is to protect water quality, and finally, and the fourth goal is to protect and restore their habitat. There was no change in biological information, threats, or listing from the previous 5-year review since little research has been done on the actual crustacean. However, the 5-year plan emphasizes the importance of following the recovery plan that was established in 2019.[8]

Recovery plan

The recovery plan's strategy involves preserving, restoring, and managing the Noel's Amphipod's aquatic habitat in order to support resilient populations of these species.The recovery plan aims to maintain and protect the population size through securing good water quantity and quality, and protecting their habitat's land. This approach also includes controlling invasive species.[9]

It is important to collaborate with conservation partners to achieve the goals listed in the five-year review while also providing the communities with enough water themselves. This is done through community engagement and promoting the importance of Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge and its biodiversity.[9]

Recovery of this species requires that we maintain and protect Noel's amphipods and their habitats so that the species stabilizes and can then be removed from the endangered species list. This is attainable and will happen if this list of needs are met. First, secure the long-term survival of the species with the appropriate number, size, and distribution. Second, preserve water quantity and quality. Third, reduce the threats to the species and its ecosystem so Noel's Amphipods can reestablish a stable population size.[9]

It would also be beneficial to conduct more research to better understand their species patterns, genetic diversity, and then be able to identify new sites for species’ introductions. It is critical to the conservation of this species that we develop long term management strategies and educational programs to help protect the Noel's Amphipod. By teaching the immediate surrounding community about their habitat needs and importance, we increase our capacity for protecting them.[9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Lang, B.; Pollock, C.M. (2000). "Gammarus desperatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2000: e.T8902A12937542. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T8902A12937542.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/8902/12937542. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ↑ "Noel's Amphipod (Gammarus desperatus) species profile". Environmental Conservation Online System. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. October 10, 2010. http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=K023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Listing Roswell springsnail, Koster's tryonia, Pecos assiminea, and Noel's amphipod as Endangered With Critical Habitat". Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government: 6459–6479. 2002-12-02. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2002/02/12/02-3140/endangered-and-threatened-wildlife-and-plants-listing-roswell-springsnail-kosters-tryonia-pecos.

- ↑ Goedmakers, Annemarie (1972). "Gammarus fossarum Koch, 1835: redescription based on neotype material and notes on its local variation (Crustacea, Amphipoda)". Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde 42 (2): 124–138. doi:10.1163/26660644-04202002.

- ↑ Delong, Michael (April 1992). "A New Species of Gammarus (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Gammaridae) from the Lower Mississippi River, Louisiana". The American Midland Naturalist 127 (2): 241–247. doi:10.2307/2426530. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2426530.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 "Recovery and Conservation Plan for Four Invertebrate Species: Noel's amphipod (Gammarus desperatus), Pecos assiminea (Assiminea pecos), Koster's springsnail (Juturnia kosteri), and Roswell springsnail (Pyrgulopsis roswellensis)". New Mexico Department of Game and Fish: 5–43. January 2005. https://www.wildlife.state.nm.us/download/conservation/species/invertebrates/recovery-plans/Chaves-County-Invertebrates-Plan.pdf.

- ↑ Thorp, James; Covich, Alan (2001), "Dedication", Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates (Elsevier): pp. v, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-690647-9.50030-2, ISBN 9780126906479

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Noel's amphipod (Gammarus desperatus), Koster's springsnail (Juturnia kosteri), Roswell springsnail (Pyrgulopsis roswellensis), and Pecos assiminea (Assiminea pecos) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: 1–10. May 2020. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/species_nonpublish/3348.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "Final Recovery Plan for Four Invertebrate Species of the Pecos River Valley: Noel's amphipod (Gammarus desperatus), Koster's springsnail (Juturnia kosteri), Roswell springsnail (Pyrgulopsis roswellensis), and Pecos assiminea (Assiminea pecos) Southwest Region, Albuquerque, New Mexico". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: 1–83. July 26, 2019. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/Final%20Recovery%20Plan%20Four%20Invertebrates%20of%20Pecos%20River%20Valley_1.pdf.

Wikidata ☰ Q309203 entry

|